12 Integrated Rate Laws; Application of Pseudo-First Order (Flooding) Techniques (M13Q5)

Learning Objectives

- Given the initial concentration of a reactant, use integrated rate laws to determine the concentration of reactant after a given time has passed or how long it will take for the reactant to reach a certain concentration.

| First Order | Second Order | Zero Order | - Apply the experimental technique of flooding to reactions involving more than one reactant to determine reaction orders, the observed rate constant (kobs), the rate constant (k), and the rate law for a reaction.

| Flooding | - Evaluate experimental data using the integrated rate law method to determine reaction orders, the rate constant, and the rate law for a reaction.

| Key Concepts and Summary | Key Equations | Glossary | End of Section Exercises |

Integrated Rate Laws

The rate laws we have seen so far relate the rate and the concentrations of reactants. We can also determine a second form of each rate law that relates the concentrations of reactants and time. These are called integrated rate laws. We can use an integrated rate law to determine the amount of reactant or product present after a period of time or to estimate the time required for a reaction to proceed to a certain extent. For example, an integrated rate law is used to determine the length of time a radioactive material must be stored for its radioactivity to decay to a safe level.

Please note: The integrated rate laws discussed in this text are derived for a reaction with reactant stoichiometric coefficient of 1, as in A → Product. If the coefficient was different, such as 2A → Product, the integrated rate laws would be slightly different.

First-Order Reactions

For the first-order reaction:

A → Product

the rate is:

rate = [latex]\frac{-\Delta[A]}{\Delta\;t}[/latex]

Because this is a first-order reaction, the rate law is:

rate = k[A]

These two expressions can be combined:

rate = [latex]\frac{-\Delta[A]}{\Delta\;t}[/latex] = k[A]

Calculus can used to integrate this expression to give us a useful equation relating the rate constant, k, with [A]0, the initial concentration, and [A]t, the concentration after time, t, has passed.

Example 1

The Integrated Rate Law for a First-Order Reaction

The rate constant for the first-order decomposition of cyclobutane, C4H8 at 500 °C is 9.2 × 10−3 s−1:

C4H8(g) → 2 C2H4(g)

How long will it take for 80.0% of a sample of C4H8 to decompose?

Solution

We use the integrated form of the rate law to answer questions regarding time:

There are four variables in the rate law, so if we know three of them, we can determine the fourth. In this case we know [A]0, [A]t, and k, and need to find t.

The initial concentration of C4H8, [A]0, is not provided, but the provision that 80.0% of the sample has decomposed is enough information to solve this problem. Let x be the initial concentration, in which case the concentration after 80.0% decomposition is 20.0% of x or 0.200x. Rearranging the rate law to isolate t and substituting the provided quantities yields:

t = ln[latex](\frac{[A]_{t}}{[A]_{0}})\;\times\;[/latex] - [latex]\frac{1}{k}[/latex]

t = ln[latex](\frac{0.200x}{x})\;\times\;[/latex] - [latex]\frac{1}{9.2 \times 10^{-3}s^{-1}}[/latex]

t = 1.7 x 102 s

Check Your Learning

Iodine-131 is a radioactive isotope that is used to diagnose and treat some forms of thyroid cancer. Iodine-131 decays to xenon-131 according to the equation:

131I → 131Xe + e-

All radioactive decay is first order. The rate constant is 0.138 days−1. How many days will it take for 90% of the 131I in a 0.500 M solution of this substance to decay to 131Xe?

Answer:

16.7 days

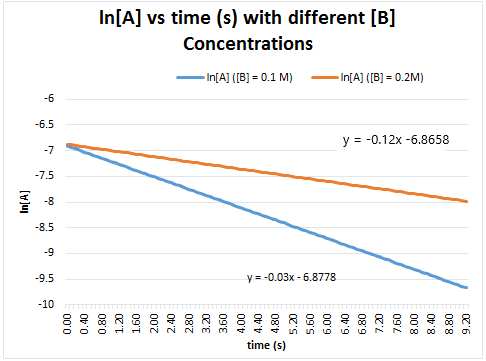

We can use integrated rate laws with experimental data of concentration and time over the course of a reaction to graphically determine the order and rate constant of a reaction.

The integrated rate law can be rearranged to a standard linear equation format (y = mx + b, where m = slope and b = the y-intercept):

ln[A]t = -kt + ln[A]0

y = mx + b_

Thus, a plot of ln[A] versus t for a first-order reaction is a straight line with a slope of −k and a y-intercept of ln[A]0. If a set of rate data are plotted in this fashion but do not result in a straight line, the reaction is not first order in A.

![A graph is shown with the label “Time” on the x-axis and “[A]” on the y-axis. It has a curved line A second graph is shown with the label “Time” on the x-axis and “ln[A]” on the y-axis. This graph has a negatively sloped linear line with a non-zero y-intercept.](https://wisc.pb.unizin.org/app/uploads/sites/418/2019/08/M2Q5-lnA-vs-t-plot.png)

Example 2

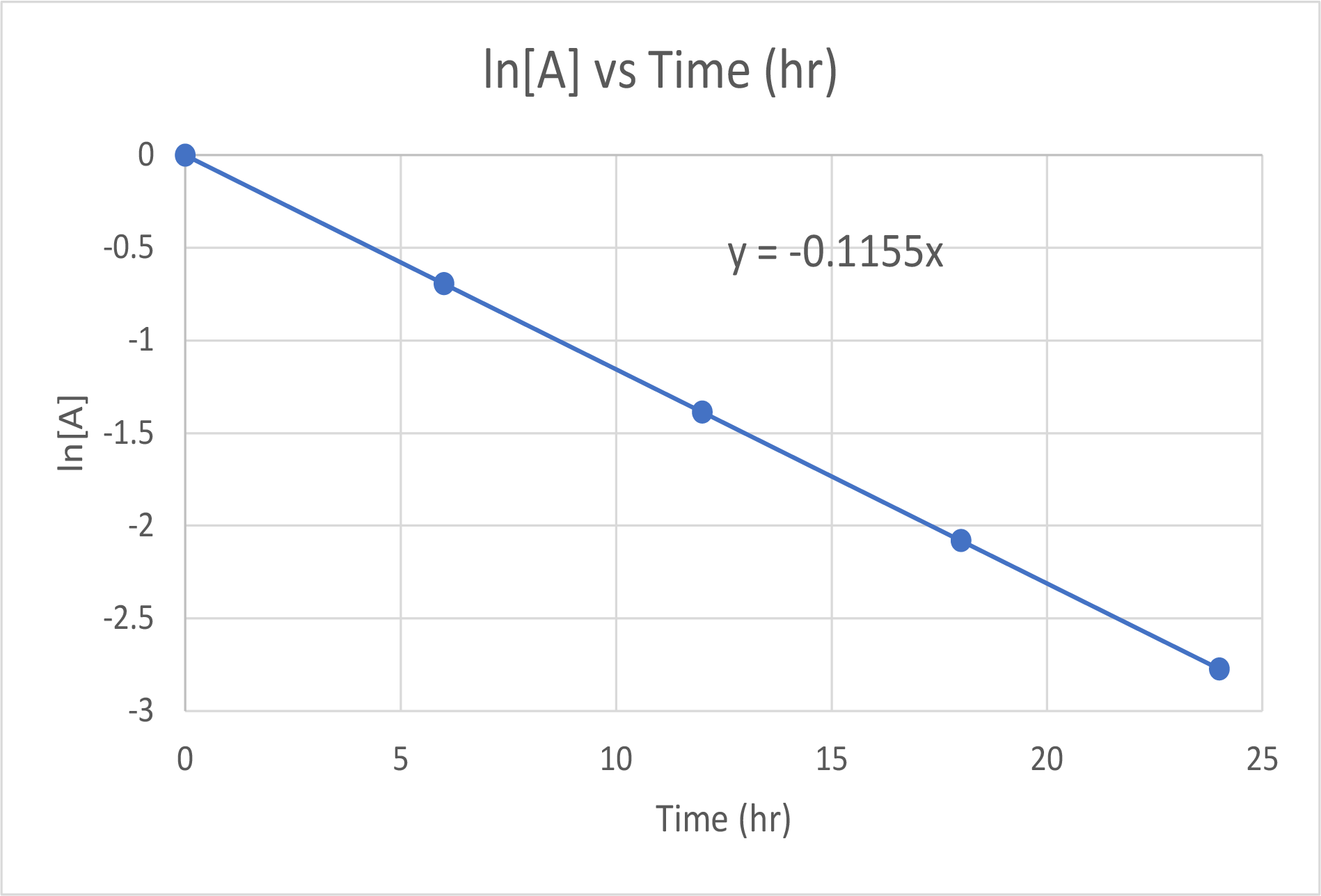

Determination of Reaction Order by Graphing

For the first-order reaction A → B, determine the rate constant for the rate of decomposition of A from this data:

| [A] | Time (hr) |

| 1.000 M | 0 |

| 0.500 M | 6 |

| 0.250 M | 12 |

| 0.125 M | 18 |

| 0.0625 M | 24 |

Solution

First, consider the most useful way to use this data. Because it is a first-order reaction, plot the ln[A] vs time:

| Trial | Time (hr) | [A] (M) | ln[A] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 1.000 | 0.0 |

| 2 | 6.00 | 0.500 | −0.693 |

| 3 | 12.00 | 0.250 | −1.386 |

| 4 | 18.00 | 0.125 | −2.079 |

| 5 | 24.00 | 0.0625 | −2.772 |

The plot of ln[A] versus time is linear, thus we have verified that the reaction may be described by a first-order rate law.

The rate constant for a first-order reaction is equal to the negative of the slope of the plot of ln[H2O2] versus time where:

slope = [latex]\frac{\Delta\;y}{\Delta\;x}[/latex] = [latex]\frac{\Delta\;ln[A]}{\Delta\;time}[/latex]

slope = [latex]\frac{-1.386\;\;-\;\;(-0.693)}{12.00h\;\;-\;\;6.00h}[/latex] = -0.1155 hr-1

Check Your Learning

Graph the following data to determine whether the reaction, A → B + C, is first order.

| Trial | Time (s) | [A] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.0 | 0.220 |

| 2 | 8.0 | 0.144 |

| 3 | 12.0 | 0.110 |

| 4 | 16.0 | 0.088 |

| 5 | 20.0 | 0.074 |

Answer:

The plot of ln[A] vs. t is not a straight line. The equation is not first order:

Second-Order Reactions

For the second-order reaction:

A → Product

the rate is:

rate = [latex]\frac{-\Delta[A]}{\Delta\;t}[/latex]

Because this is a second-order reaction, the rate law is:

rate = k[A]2

These two expressions can be combined:

rate = [latex]\frac{-\Delta[A]}{\Delta\;t}[/latex] = k[A]2

Calculus can used to integrate this expression to give us a useful equation relating the rate constant, k, with [A]0, the initial concentration, and [A]t, the concentration after time, t, has passed.

Example 3

The Integrated Rate Law for a Second-Order Reaction

The reaction of butadiene gas (C4H6) with itself produces C8H12 gas as follows:

2 C4H6(g) → C8H12(g)

The reaction is second order with a rate constant equal to 5.76 × 10−2M-1min-1 under certain conditions. If the initial concentration of butadiene is 0.200 M, what is the concentration remaining after 10.0 min?

Solution

We use the integrated form of the rate law to answer questions regarding time. For a second-order reaction, we have:

We know three variables in this equation: [A]0 = 0.200 M, k = 5.76 × 10−2 M-1min-1, and t = 10.0 min. Therefore, we can solve for [A], the fourth variable:

[latex]\frac{1}{[A]_{t}}[/latex] = (5.76 x 10-2 M-1min-1)(10.0 min) + [latex]\frac{1}{0.200 M}[/latex]

[latex]\frac{1}{[A]_{t}}[/latex] = 5.58 M-1

[A] = 0.179 M

Therefore 0.179 M of butadiene remain at the end of 10.0 min, compared to the 0.200 M that was originally present.

Check Your Learning

If the initial concentration of butadiene is 0.0200 M, what is the concentration remaining after 20.0 min?

Answer:

0.0195 M

As with a first-order reaction, we can use integrated rate laws with experimental data of concentration and time over the course of a reaction to graphically determine the order and rate constant of a reaction.

The integrated rate law can be rearranged to a standard linear equation format (y = mx + b, where m = slope and b = the y-intercept):

[latex]\frac{1}{[A]_{t}}[/latex] = kt + [latex]\frac{1}{[A]_{0}}[/latex]

y = mx + b_

Thus, a plot of [latex]\frac{1}{[A]}[/latex] versus t for a second-order reaction is a straight line with a slope of +k and a y-intercept of [latex]\frac{1}{[A]_{0}}[/latex]. If a set of rate data are plotted in this fashion but do not result in a straight line, the reaction is not second order in A.

![A graph is shown with the label “Time” on the x-axis and “[A]” on the y-axis. It has a curved line A second graph is shown with the label “Time” on the x-axis and “1/[A]” on the y-axis. This graph has a psitively sloped linear line with a non-zero y-intercept.](https://wisc.pb.unizin.org/app/uploads/sites/418/2019/08/M2Q5-second-order-plot.png)

Example 4

Determination of Reaction Order by Graphing

Test the data given to show whether the dimerization of C4H6 is a first- or a second-order reaction.

Solution

| Time (s) | [C4H6] (M) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1.00 × 10−2 |

| 1600 | 5.04 × 10−3 |

| 3200 | 3.37 × 10−3 |

| 4800 | 2.53 × 10−3 |

| 6200 | 2.08 × 10−3 |

In order to distinguish a first-order reaction from a second-order reaction, we plot ln[C4H6] versus t and compare it with a plot of [latex]\frac{1}{[C_{4}H_{6}]}[/latex] versus t. The data used for these plots in in the table below:

| Time (s) | [latex]\frac{1}{[C_{4}H_{6}]}[/latex] M-1 | ln[C4H6] |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100 | −4.605 |

| 1600 | 198 | −5.289 |

| 3200 | 296 | −5.692 |

| 4800 | 395 | −5.978 |

| 6200 | 481 | −6.175 |

The plots are shown below. As you can see, the plot of ln[C4H6] versus t is not linear, therefore the reaction is not first order. The plot of versus t is linear, indicating that the reaction is second order.

![Two graphs are shown, each with the label “Time ( s )” on the x-axis. The graph on the left is labeled, “l n [ C subscript 4 H subscript 6 ],” on the y-axis. The graph on the right is labeled “1 divided by [ C subscript 4 H subscript 6 ],” on the y-axis. The x-axes for both graphs show markings at 3000 and 6000. The y-axis for the graph on the left shows markings at negative 6, negative 5, and negative 4. A decreasing slightly concave up curve is drawn through five points at coordinates that are (0, negative 4.605), (1600, negative 5.289), (3200, negative 5.692), (4800, negative 5.978), and (6200, negative 6.175). The y-axis for the graph on the right shows markings at 100, 300, and 500. An approximately linear increasing curve is drawn through five points at coordinates that are (0, 100), (1600, 198), (3200, 296), and (4800, 395), and (6200, 481).](https://wisc.pb.unizin.org/app/uploads/sites/418/2019/08/Chem104_M2Q5_Ex4a.png)

Check Your Learning: Does the following data fit a second-order rate law?

| Time (s) | [A] (M) |

|---|---|

| 5 | 0.952 |

| 10 | 0.625 |

| 15 | 0.465 |

| 20 | 0.370 |

| 25 | 0.308 |

| 35 | 0.230 |

Answer:

![A graph, with the title “1 divided by [ A ] vs. Time” is shown, with the label, “Time ( s ),” on the x-axis. The label “1 divided by [ A ]” appears left of the y-axis. The x-axis shows markings beginning at zero and continuing at intervals of 10 up to and including 40. The y-axis on the left shows markings beginning at 0 and increasing by intervals of 1 up to and including 5. A line with an increasing trend is drawn through six points at approximately (4, 1), (10, 1.5), (15, 2.2), (20, 2.8), (26, 3.4), and (36, 4.4).](https://wisc.pb.unizin.org/app/uploads/sites/418/2019/08/Chem104_M2Q5_Ex4.png)

Yes. The plot of vs. t is linear.

Zero-Order Reactions

For the zero-order reaction:

A → Product

the rate is:

rate = [latex]\frac{-\Delta[A]}{\Delta\;t}[/latex]

Because this is a zero-order reaction, the rate law is:

rate = k[A]0 = k

These two expressions can be combined:

rate = [latex]\frac{-\Delta[A]}{\Delta\;t}[/latex] = k

Calculus can used to integrate this expression to give us a useful equation relating the rate constant, k, with [A]0, the initial concentration, and [A]t, the concentration after time, t, has passed.

[A]t = -kt + [A]0

y = mx + b_

The integrated rate law for a zero-order reaction has the form of the equation of a straight line. A plot of [A] versus t for a zero-order reaction is a straight line with a slope of −k and a y-intercept of [A]0.

![A graph is shown with the label “Time” on the x-axis and “[A]” on the y-axis. It has a negatively sloped linear line.line](https://wisc.pb.unizin.org/app/uploads/sites/418/2019/08/M2Q5-zero-order-plot-1.png)

Experimental Technique Using Integrated Rate Laws and the Flooding Method

The integrated rate laws are quite useful when determining the reaction order and rate constants using all the data from a single experimental trial run. However, we’ve only considered integrated rate laws for reactions involving one reactant, whereas many reactions involve two or more reactants—how can we use integrated rate laws to find the reaction order and rate constants for those reactions? From the previous chapter, we can use the "flooding" method, where one reactant is at a much larger concentration than the other, making that reactant appear to have a constant concentration with respect to the concentration change that occurs with the smaller concentration reactant.

Let’s consider the reaction:

A + B → Products

where

To isolate the effect of reactant A on the reaction rate, we can run the reaction under a large excess of reactant B, i.e., flooding the reaction mixture with B so that A is the limiting reagent, and reactant B concentration effectively remains constant during the reaction because its consumption is so small that the change in concentration becomes negligible. Under this condition, the effectively constant B concentration and the k constant can be consolidated into a new a rate constant, kobs, where:

kobs = k[B]n

By replacing k[B]n with kobs in the rate law, the rate law can be written as:

This rate law equation derived from the flooding technique allows us to use the integrated rate laws and experimental data to determine the reaction order with respect to reactant A and kobs.

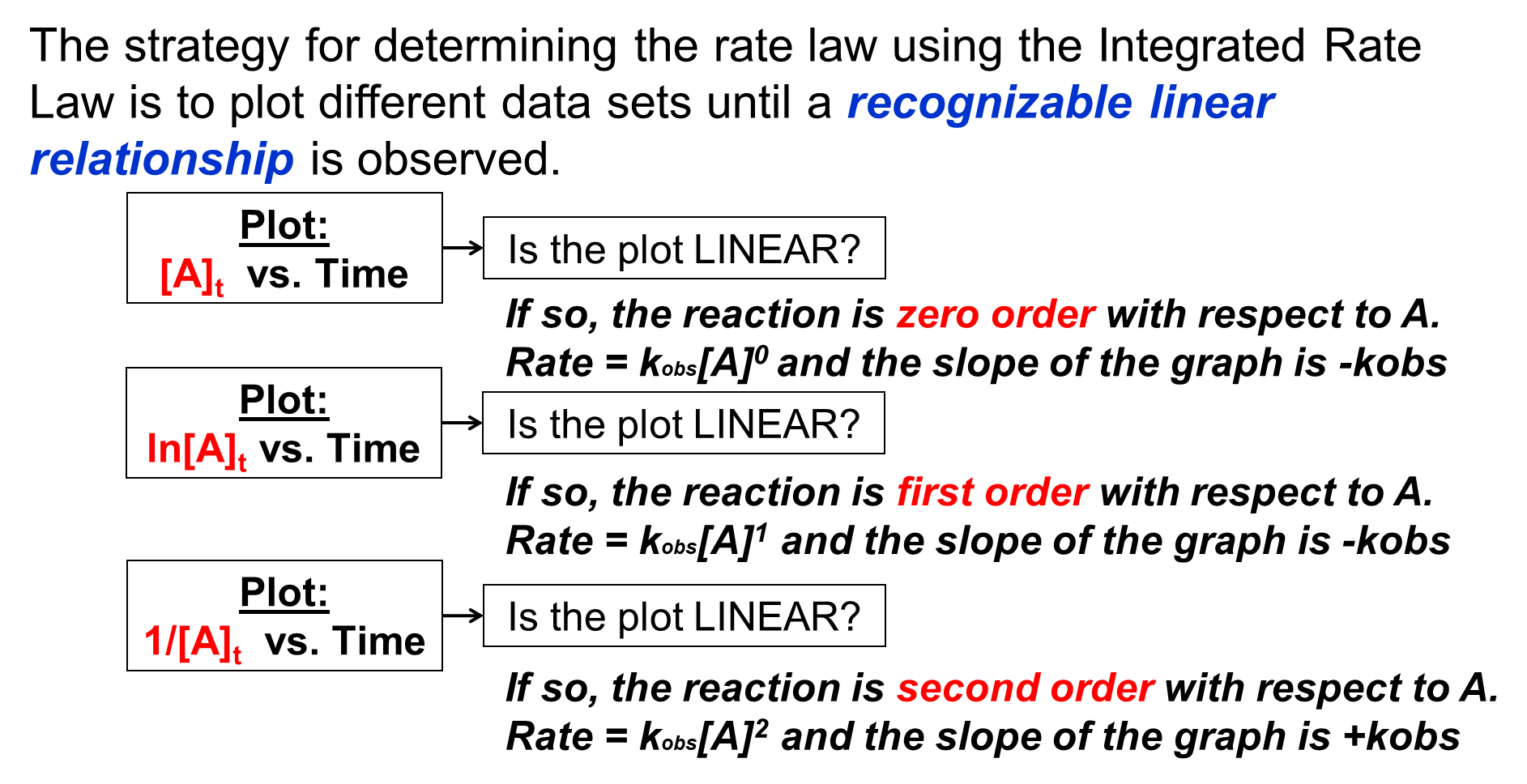

After measuring the concentration of A as the reaction progresses, we can produce plots of [A] vs time, ln[A] vs time, and [latex]\frac{1}{[A]}[/latex] vs time. By identifying which plot results in a linear line of data points, the order of the reaction with respect to A can be determined. The absolute value of the slope of that linear plot will be equal to kobs. An outline of the strategy to be employed can be seen below.

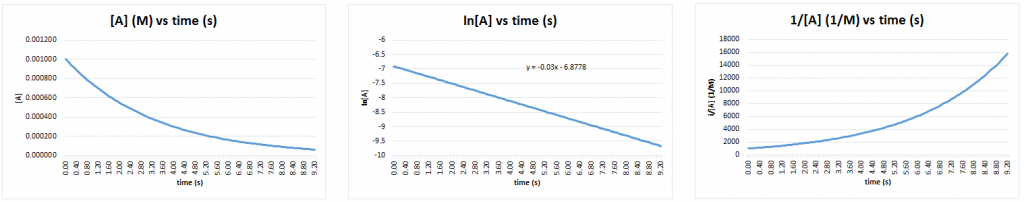

In this example, after measuring the concentration of A as the reaction progresses, plots of [A] vs time, ln[A] vs time, and [latex]\frac{1}{[A]}[/latex] vs time are produced, as seen in Figure 4. The ln[A] vs time plot is linear, so the reaction is first-order with respect to A and the slope of the plot equals -kobs1 (this experiment will involve a number of trials and so the kobs has been given a subscript of "1" to keep track of the data).

We can then run another trial with a different concentration of B, 0.2 M, which is still in large excess. The plot of ln[A]t vs time would will still be linear but will yield a different slope corresponding to -kobs2. This can be seen in Figure 5.

The ratio of the two kobs can be used to find the order of B:

[latex] \frac{k_{obs2}}{k_{obs1}}[/latex] = [latex]\frac{k[B]_{2}^n}{k[B]_{1}^n}[/latex] = [latex]\left(\begin{array}{c}\frac{[B]_2^n}{[B]_1^n}\end{array}\right)^{n}[/latex]

[latex]\frac{0.12}{0.03}[/latex] = [latex]\left(\begin{array}{c}\frac{0.2 M}{0.1 M}\end{array}\right)^{n}[/latex]

These values can be put together to find the complete rate law:

rate = k[A][B]2

Key Concepts and Summary

By integrating the first, second, and zero order rate laws, an equation that relates the rate constant, the time (t), the initial concentration of a reactant, and the concentration of the reactant at time, t. These integrated rate laws are powerful tools that, after we know the order of the reactant, we can predict how long it will take for a reaction to occur or how much reactant will be remaining after a certain amount of time. The slope of an integrated rate law plot can be used to find the rate constant, k. We can also use our understanding of flooding from the previous section and relate it to integrated rate laws to find the order of each reactant in a simple way. Most commonigly, the plot axes of a linear plot give us the order of the reactant on the graph y-axis. Then, the initial slopes can be compared to find the order of the flooded reactant.

Key Equations

- First Order: ln [A]t = -kt + ln [A]0 or [A]t = [A]0e-kt

- Second Order: [latex]\frac{1}{[A]_{t}}[/latex] = kt + [latex]\frac{1}{[A]_{0}}[/latex]

- Zero Order: [A]t = -kt + [A]0

- Flooding: rate = k[A]m[B]n | rate = kobs[A]m | kobs = k[B]n

Glossary

integrated rate laws

a form of each rate law that relates the concentration of reactants and time

Chemistry End of Section Exercises

- Describe how graphical methods can be used to determine the order of a reaction and its rate constant from a series of data that includes the concentration of A at varying times.

- Use the data provided to graphically determine the order and rate constant of the following reaction:

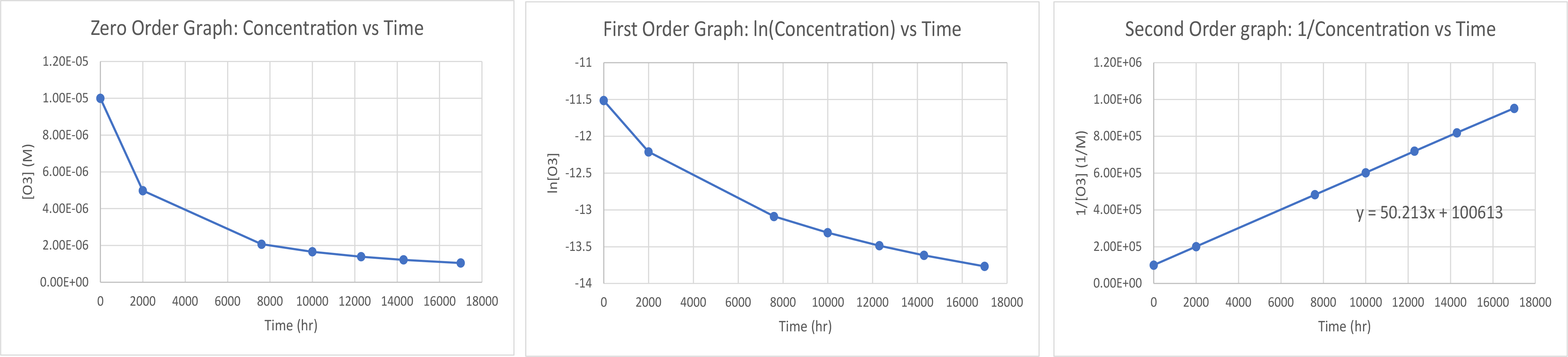

SO2Cl2(g) → SO2(g) + Cl2(g)Time (s) [SO2Cl2] (M) 0 0.100 5.00 × 103 0.0896 1.00 × 104 0.0802 1.50 × 104 0.0719 2.50 × 104 0.0577 3.00 × 104 0.0517 4.00 × 104 0.0415 - Pure ozone decomposes slowly to oxygen, 2 O3(g) → 3 O2(g). Use the data provided in a graphical method and determine the order and rate constant of the reaction.

Time (h) [O3] (M) 0 1.00 × 10-5 2.0 × 103 4.98 × 10-6 7.6 × 103 2.07 × 10-6 1.00 × 104 1.66 × 10-6 1.23 × 104 1.39 × 10-6 1.43 × 104 1.22 × 10-6 1.70 × 104 1.05 × 10-6 - You are asked to calculate a how much of a reactant is left after a certain period of time for a spontaneous zero-order decomposition reaction; however, you have been given three possible rate constants: 0.100 M-1 s-1, 0.0075 M s-1, and 7.5 x 103 s-1. Which rate constant should you use and why did you choose that one?

- The thermal decomposition of phosphine gas, PH3, into elemental phosphorous, P4 (a gas), and hydrogen gas is a first-order reaction, with k = 0.0198 s-1 at room temperature.

- Write the balanced reaction for this process.

- If 0.125 g of PH3 is allowed to decompose, how much is left after 2.50 minutes?

- How long will it take for 65% of a phosphine sample to decompose?

- The rate constant for the reaction:

2 NOBr(g) → 2 NO(g) + Br2(g)

is 0.80 M-1 s-1 at 10.0 °C. If the reaction starts with 0.075 M NOBr, what is the concentration of NOBr after 45 seconds? - Determine the rate constant of a zero-order reaction if it takes 3.00 minutes for its initial concentration of 2.00 M to reduce to 0.50 M.

Answers to Chemistry End of Section Exercises

- Using time and concentration data acquired as a reaction progresses may be used to find the order of reactants and the rate constant of a reaction.

- A linear trend line when plotting concentration vs time indicates the order is zero with regard to the reactant. The rate constant is the absolute value of the slope of the trend line.

- A linear trend line when plotting the natural log of concentration vs time indicates the order is first with regard to the reactant. The rate constant is the absolute value of the slope of the trend line.

- A linear trend line when plotting 1/concentration vs time indicates the order is second with regard to the reactant. The rate constant is the absolute value of the slope of the trend line.

This is most simply done when there is only one reactant but may be combined with flooding methods to find orders of reactants when there is more than one reactant present.

- Plotting a graph of ln[SO2Cl2] versus t reveals a linear trend; therefore we know this is a first-order reaction. The best fit slope of the trend line is −2.20 × 105 s−1 so k = 2.20 × 105 s-1.

![A graph, with the title “1 divided by [ A ] vs. Time” is shown, with the label, “Time ( s ),” on the x-axis. The label “1 divided by [ A ]” appears left of the y-axis. The x-axis shows markings beginning at zero and continuing at intervals of 10 up to and including 40. The y-axis on the left shows markings beginning at 0 and increasing by intervals of 1 up to and including 5. A line with an increasing trend is drawn through six points at approximately (4, 1), (10, 1.5), (15, 2.2), (20, 2.8), (26, 3.4), and (36, 4.4).](https://wisc.pb.unizin.org/app/uploads/sites/418/2019/08/Chem104_M2Q5_EOCproblem2-1024x272.png)

- Plotting a graph of 1/[O3] vs time produces a linear trend line, so the reaction is second order. The best fit slope of the trend line is 50.1 M-1 hr-1 so k = 50.1 M−1 hr−1

- 0.0075 M s-1; The rate constant units enable us to determine which is the rate constant.

-

- 4 PH3(g) → P4(g) + 6 H2(g)

- 0.00641 g

- 53 seconds

- 0.020 M

- 0.50 M min-1

Feedback/Errata