D17.2 Energy, Temperature, and Heat

In the activity about how evaporation of perspiration cools your skin, we noted that when some liquid water evaporated, the liquid-phase molecules that remained had lower average kinetic energy, and hence lower temperature. Because the water was cooler than your skin, energy transferred via molecular collisions from skin to liquid water, cooling the skin. We now explore such energy transfers in more detail.

Thermal energy is kinetic energy associated with the random motion of atoms and molecules. When thermal energy is transferred into an object, its atoms and molecules move faster on average (higher KEaverage), the object’s temperature increases, and we say that the object is “hotter”. When thermal energy is transferred out of an object, its atoms and molecules move more slowly on average (lower KEaverage), the object’s temperature decreases, and we say that the object is “colder”.

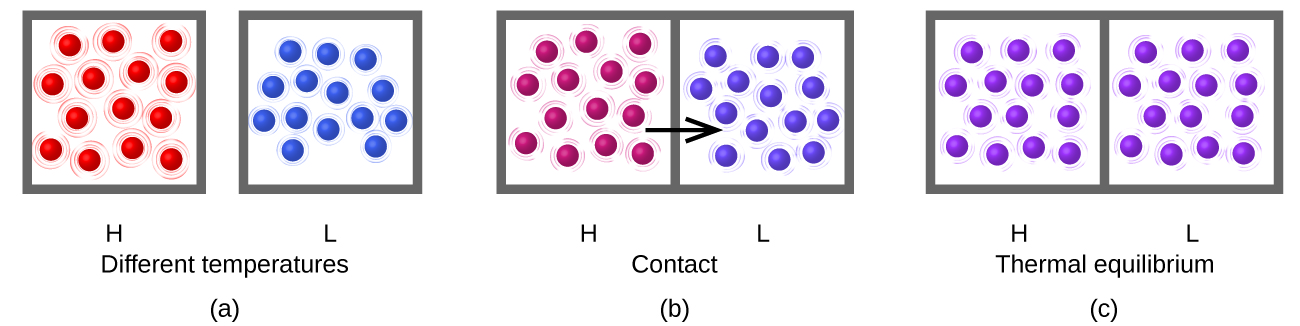

Heating (or heat), represented by q, is the transfer of thermal energy between two samples of matter at different temperatures. Heat transfer of energy continues until both objects have reached the same temperature; that is, until thermal equilibrium has been reached.

Consider what happens during the heat-transfer process: energy transfer occurs as a result of collisions between molecules. (The boxes drawn around the groups of molecules in the figure are to delineate which molecules are in which group, but when the samples are in thermal contact some molecules in sample H contact some molecules in sample L.) On average the molecules in the hotter sample move faster than the molecules in the cooler sample, so on average a molecule from the hotter sample can transfer more energy than a molecule in the cooler sample. Thus, as long as the temperature is different, energy transfers from hotter to cooler.

After thermal equilibrium has been reached, energy transfer by molecular collisions continues to occur, but now the probability of energy transfer from sample H to sample L equals the probability of energy transfer from sample L to sample H. On the macroscopic scale there is no change in temperature of either sample, but on the atomic scale energy transfer continues at equal rates H→L and L→H. The atoms do not stop moving and transferring energy but the transfers are equal and opposite. This is a general characteristic of equilibrium.

Heat Capacity and Calorimetry

The same quantity of energy causes a different temperature change depending on the nature of the substance. The specific heat capacity (c) of a substance is the heating required to raise the temperature of 1 g of a substance by 1 °C; that is, to change the object’s temperature by ΔT = Tfinal − Tinitial = T2 − T1 = 1 K. (Because 1 K is the same size as 1 °C, ΔT has the same numeric value whether expressed in K or °C.)

If we know the mass, m, of a sample and its specific heat capacity, c, we can calculate the heat transfer of energy (q) to or from the sample by measuring the temperature change during heating or cooling:

The sign of ΔT determines the sign of q and tells us whether the substance is being heated (positive value for q) or cooled (negative q ).

Exercise: Heat Transfer of Energy

This exercise is an example of a technique called calorimetry in which heat transfers of energy are measured. In calorimetry it is useful to define a system, the substance(s) undergoing a physical or chemical change, and the surroundings, everything else that can exchange energy with the system.

A process in which there is heat transfer from the system to the surroundings (a process that heats the surroundings) is an exothermic process. For example, the combustion reaction that occurs in the flame of a lighted match is exothermic. A process in which there is heat transfer from the surroundings to the system (a process that cools the surroundings) is an endothermic process. Vaporization of argon (or some other liquid) is an example of an endothermic process.

Please use this form to report any inconsistencies, errors, or other things you would like to change about this page. We appreciate your comments. 🙂 (Note that we cannot answer questions via the google form. If you have a question, please post it on Piazza.)