D4.7 Unpaired Electrons and Magnetism

One way chemists have discovered information about electron configurations of ions involves magnetism. You are probably familiar with refrigerator magnets, iron magnets, or neodymium (rare earth) magnets. These exhibit ferromagnetism, a strong attraction to a magnetic field that is easily observable and sometimes can be made permanent. All substances exhibit diamagnetism, a very weak repulsion from a magnetic field that can only be observed in extremely large magnetic fields. Because diamagnetism is so weak, it is usually too small to notice.

Left-click here for optional material: Diamagnetism

Click here to see videos of a water droplet and a live frog levitated by repulsion from a very strong magnetic field.

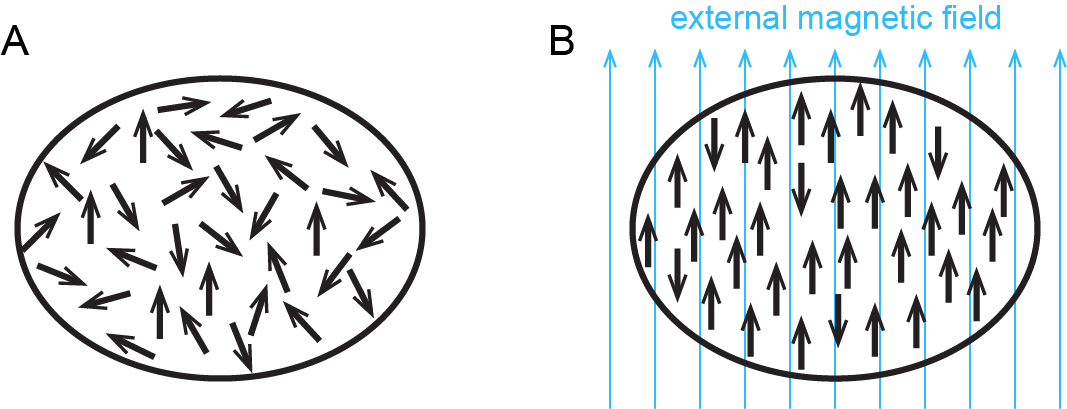

In addition to diamagnetism, some substances also exhibit paramagnetism, an attraction to a magnetic field that is not as strong as ferromagnetism but much stronger than diamagnetic repulsion. Paramagnetism arises due to the presence of unpaired electrons. Each electron has a tiny magnetic field; that is, each electron is a tiny magnet. When a macroscopic magnet comes near a paramagnetic substance, most of the unpaired electron magnets align with the magnetic field, causing the substance to be attracted to the magnet (Figure: Paramagnetism).

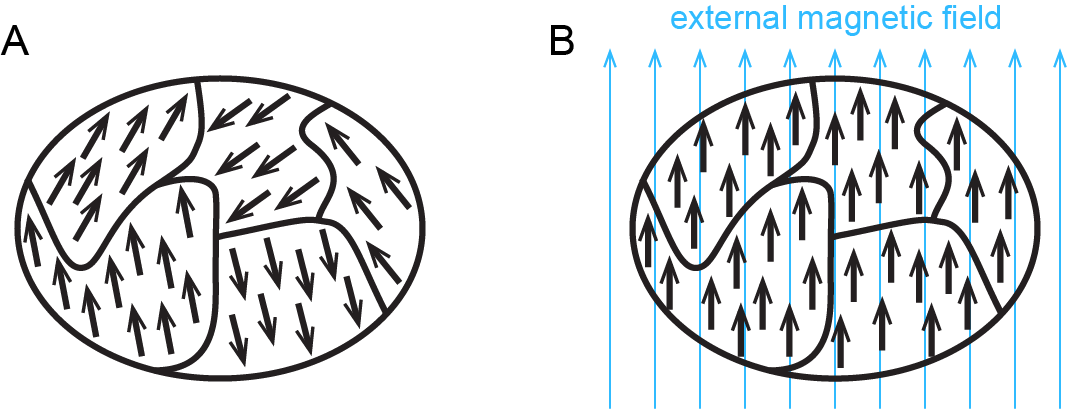

Figure: Ferromagnetism shows how ferromagnetism differs from paramagnetism.

When electrons are paired in an orbital, their opposite magnetic moments create opposite magnetic fields that cancel each other: substances with all electrons paired are neither paramagnetic nor ferromagnetic. They exhibit only diamagnetism and are said to be diamagnetic. For example, argon has a ground state electron configuration of 1s22s22p63s23p6, where each subshell is full and each orbital therein contains a pair of electrons with opposite spins. Hence, a sample of argon is diamagnetic.

Paramagnetic and diamagnetic materials do not act as permanent magnets. A magnetic field is required to align the magnetic moments and make them magnetic. The magnitude of paramagnetism can be measured by weighing a sample with a highly sensitive balance and then weighing it again with a strong magnet just below the sample. A sample that is attracted to the magnet appears heavier because the magnet attracts it downward. The increase in apparent weight is proportional to the number of unpaired electrons.

Exercise: Diamagnetic and Paramagnetic Ions

Please use this form to report any inconsistencies, errors, or other things you would like to change about this page. We appreciate your comments. 🙂 (Note that we cannot answer questions via the google form. If you have a question, please post it on Piazza.)