Stoichiometry Demo

Stoichiometry

[latexpage]

Pre-class

Stoichiometry

The term stoichiometry refers to the quantitative relationships between amounts of reactants and products in a chemical reaction.

By understanding the stoichiometry of a particular reaction, we can determine how many molecules, moles, and grams will react with each other – and how many molecules, moles, and grams of product will be formed.

First we will explore the stoichiometry of the chemical reaction for the combustion of methane, CH4.

Combustion is defined as a reaction in which an element or compound burns in air or oxygen. Oxygen is always one of the reactants! (Combustion reactions form another classification of chemical reactions, just as precipitation reactions are a class of chemical reactions.)

The combustion of hydrogen gas forms water:

2 H2(gas) + O2(gas) → 2 H2O(liquid)

If we look at the balanced reaction for the combustion of methane (CH4), we can interpret this reaction in a number of quantitative ways.

Let’s consider the relative amounts of oxygen consumed, carbon dioxide produced, and water produced for given amounts of methane.

CH4(g) + 2 O2(g) → CO2(g) + 2 H2O(l)

| Scale of Amounts | Given Amount: CH4 | Relative Amount: O2 | Relative Amount: CO2 | Relative Amount: H2O |

| a few molecules | 1 molecule | 2 molecules | 1 molecule | 2 molecules |

| many molecules | 1000 molecules | 2000 molecules | 1000 molecules | 2000 molecules |

| moles | 1 mole | 2 moles | 1 mole | 2 moles |

| grams* | 16 grams | 64 grams | 44 grams | 36 grams |

* Notice the conservation of mass in this reaction!

80 total grams of reactants = 80 total grams of products

16 grams CH4 + 64 grams O2 = 44 grams CO2 + 36 grams H2O

Now let’s consider the stoichiometry of a different reaction: the reaction of sodium metal with water.

2 Na(s) + 2 H2O(l) → 2 NaOH(aq) + H2(g)

| Scale of Amounts | Given Amount: Na | Relative Amount: H2O | Relative Amount: NaOH | Relative Amount: H2 |

| a few atoms/ions/molecules | 2 atoms | 2 molecules | 2 Na+ ions 2 OH- ions |

1 molecule |

| many atoms/ions/molecule | 2000 atoms | 2000 molecules | 2000 Na+ ions 2000 OH- ions |

1000 molecules |

| moles | 2 moles | 2 moles | 2 moles | 1 mole |

| grams* | 46 grams | 36 grams | 80 grams | 2 grams |

*You should verify for yourself the conservation of mass for this reaction:

?? total grams of reactants = ?? total grams of products

Stoichiometry and Molar Masses

We’ve seen how the stoichiometry of a chemical reaction gives us many useful ways to think of the relative quantities involved:

- How many molecules, atoms, ions react with each other to form products

- How many moles of substances react with each other to form products

- How many grams of substances react with each other to form products

For the first two relationships listed above, it is easy to see how this information comes directly from a balanced chemical equation. The coefficients in a balanced chemical equation tells us this information directly.

But what about the third relationship? Considering the mass relationship values given in the table for the methane combustion example, how did we know that 16 grams of methane reacts with 64 grams of oxygen? This information is not readily available just by looking at the balanced chemical equation.

In order to determine the masses of reactants consumed in a reaction, as well as the masses of products formed, we need to use molar masses AND reaction coefficients.

To find the mass of one chemical from the given mass of another for a chemical reaction, we utilize dimensional analysis. The information we use as equivalent terms in this type of problem are:

- Molar mass: This value (units of g/mol) gives us the ability to determine the moles of a substance from a given mass, and vice versa.

- Reaction coefficients: This value (units of mol/mol) allows us to determine how many moles of one substance are consumed or produced relative to another.

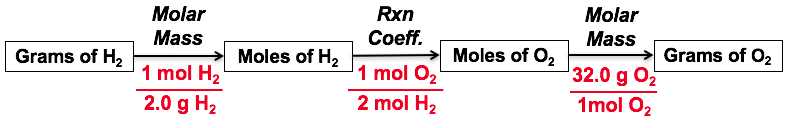

Here is an illustration of how this problem solving approach works, considering the reaction for the combustion of hydrogen: 2 H2(g) + O2(g) → 2 H2O(l)

Here is another way to show this problem-solving process:

Example: Combustion of Methane

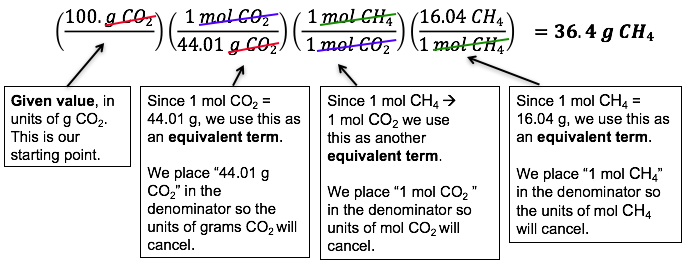

Problem: How many grams of CH4 are required to produce 100. grams of CO2?

Solution:

- Always - ALWAYS! - start with a balanced chemical equation.

CH4(g) + 2 O2(g) → CO2(g) + 2 H2O(l) - Determine your starting point (given value of 100. g CO2) and ending point (g CH4).

- Use dimensional analysis to go from (g CO2) → (mol CO2) → (mol CH4) → (g CH4)

Example: Sodium Metal in Water

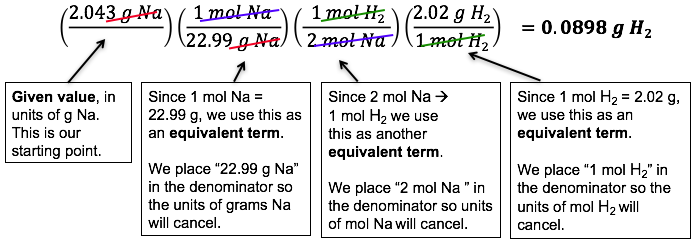

Problem: If we add 2.043 g of sodium to water, how many grams of H2 are produced?

Solution:

- Always - ALWAYS! - start with a balanced chemical equation.

2 Na(s) + 2 H2O(l) → 2 NaOH(aq) + H2(g) - Determine your starting point (given value of 2.043 g Na) and ending point (g H2).

- Use dimensional analysis to go from (g Na) → (mol Na) → (mol H2) → (g H2)

Basic Reaction Stoichiometry Quiz

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the concept of stoichiometry as it pertains to chemical reactions

- Use balanced chemical equations to derive stoichiometric factors relating amounts of reactants and products

- Perform stoichiometric calculations involving mass, moles, and solution molarity

A balanced chemical equation provides a great deal of information in a very succinct format. Chemical formulas provide the identities of the reactants and products involved in the chemical change, allowing classification of the reaction. Coefficients provide the relative numbers of these chemical species, allowing a quantitative assessment of the relationships between the amounts of substances consumed and produced by the reaction. These quantitative relationships are known as the reaction’s stoichiometry, a term derived from the Greek words stoicheion (meaning “element”) and metron (meaning “measure”). In this module, the use of balanced chemical equations for various stoichiometric applications is explored.

The general approach to using stoichiometric relationships is similar in concept to the way people go about many common activities. Food preparation, for example, offers an appropriate comparison. A recipe for making eight pancakes calls for 1 cup pancake mix, [latex]\frac{3}{4}[/latex] cup milk, and one egg. The “equation” representing the preparation of pancakes per this recipe is

If two dozen pancakes are needed for a big family breakfast, the ingredient amounts must be increased proportionally according to the amounts given in the recipe. For example, the number of eggs required to make 24 pancakes is

Balanced chemical equations are used in much the same fashion to determine the amount of one reactant required to react with a given amount of another reactant, or to yield a given amount of product, and so forth. The coefficients in the balanced equation are used to derive stoichiometric factors that permit computation of the desired quantity. To illustrate this idea, consider the production of ammonia by reaction of hydrogen and nitrogen:

This equation shows ammonia molecules are produced from hydrogen molecules in a 2:3 ratio, and stoichiometric factors may be derived using any amount (number) unit:

These stoichiometric factors can be used to compute the number of ammonia molecules produced from a given number of hydrogen molecules, or the number of hydrogen molecules required to produce a given number of ammonia molecules. Similar factors may be derived for any pair of substances in any chemical equation.

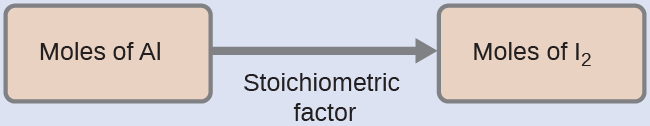

Example 1

Moles of Reactant Required in a Reaction

How many moles of I2 are required to react with 0.429 mol of Al according to the following equation (see Figure 1)?

Solution

Referring to the balanced chemical equation, the stoichiometric factor relating the two substances of interest is [latex]\frac{3 \;\text{mol I}_2}{2 \;\text{mol Al}}[/latex]. The molar amount of iodine is derived by multiplying the provided molar amount of aluminum by this factor:

Check Your Learning

How many moles of Ca(OH)2 are required to react with 1.36 mol of H3PO4 to produce Ca3(PO4)2 according to the equation [latex]3\text{Ca(OH)}_2 + 2\text{H}_3 \text{PO}_4 \longrightarrow \text{Ca}_3 \text{(PO}_4)_2 + 6\text{H}_2 \text{O}[/latex]?

Answer:

2.04 mol

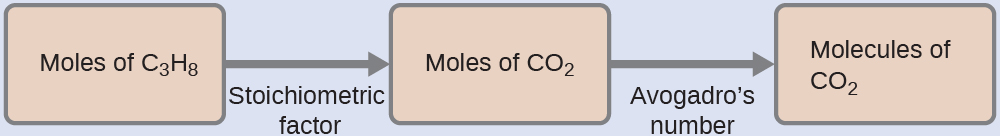

Example 2

Number of Product Molecules Generated by a Reaction

How many carbon dioxide molecules are produced when 0.75 mol of propane is combusted according to this equation?

Solution

The approach here is the same as for Example 1, though the absolute number of molecules is requested, not the number of moles of molecules. This will simply require use of the moles-to-numbers conversion factor, Avogadro’s number.

The balanced equation shows that carbon dioxide is produced from propane in a 3:1 ratio:

Using this stoichiometric factor, the provided molar amount of propane, and Avogadro’s number,

Check Your Learning

How many NH3 molecules are produced by the reaction of 4.0 mol of Ca(OH)2 according to the following equation:

Answer:

4.8 × 1024 NH3 molecules

These examples illustrate the ease with which the amounts of substances involved in a chemical reaction of known stoichiometry may be related. Directly measuring numbers of atoms and molecules is, however, not an easy task, and the practical application of stoichiometry requires that we use the more readily measured property of mass.

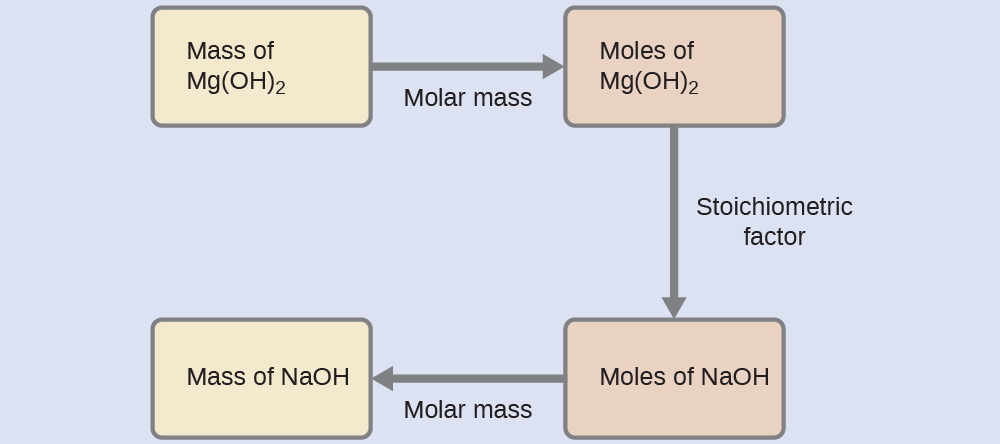

Example 3

Relating Masses of Reactants and Products

What mass of sodium hydroxide, NaOH, would be required to produce 16 g of the antacid milk of magnesia [magnesium hydroxide, Mg(OH)2] by the following reaction?

Solution

The approach used previously in Example 1 and Example 2 is likewise used here; that is, we must derive an appropriate stoichiometric factor from the balanced chemical equation and use it to relate the amounts of the two substances of interest. In this case, however, masses (not molar amounts) are provided and requested, so additional steps of the sort learned in the previous chapter are required. The calculations required are outlined in this flowchart:

Check Your Learning

What mass of gallium oxide, Ga2O3, can be prepared from 29.0 g of gallium metal? The equation for the reaction is [latex]4 \text{Ga} + 3\text{O}_2 \longrightarrow 2\text{Ga}_2 \text{O}_3.[/latex]

Answer:

39.0 g

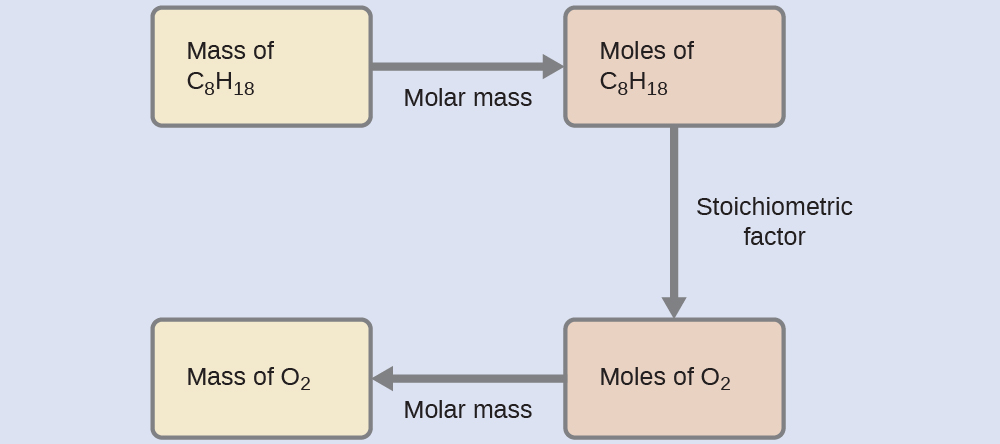

Example 4

Relating Masses of Reactants

What mass of oxygen gas, O2, from the air is consumed in the combustion of 702 g of octane, C8H18, one of the principal components of gasoline?

Solution

The approach required here is the same as for the Example 3, differing only in that the provided and requested masses are both for reactant species.

Check Your Learning

What mass of CO is required to react with 25.13 g of Fe2O3 according to the equation

[latex]\text{Fe}_2 \text{O}_3 + 3\text{CO} \longrightarrow 2\text{Fe} + 3\text{CO}_2[/latex]

Answer:

13.22 g

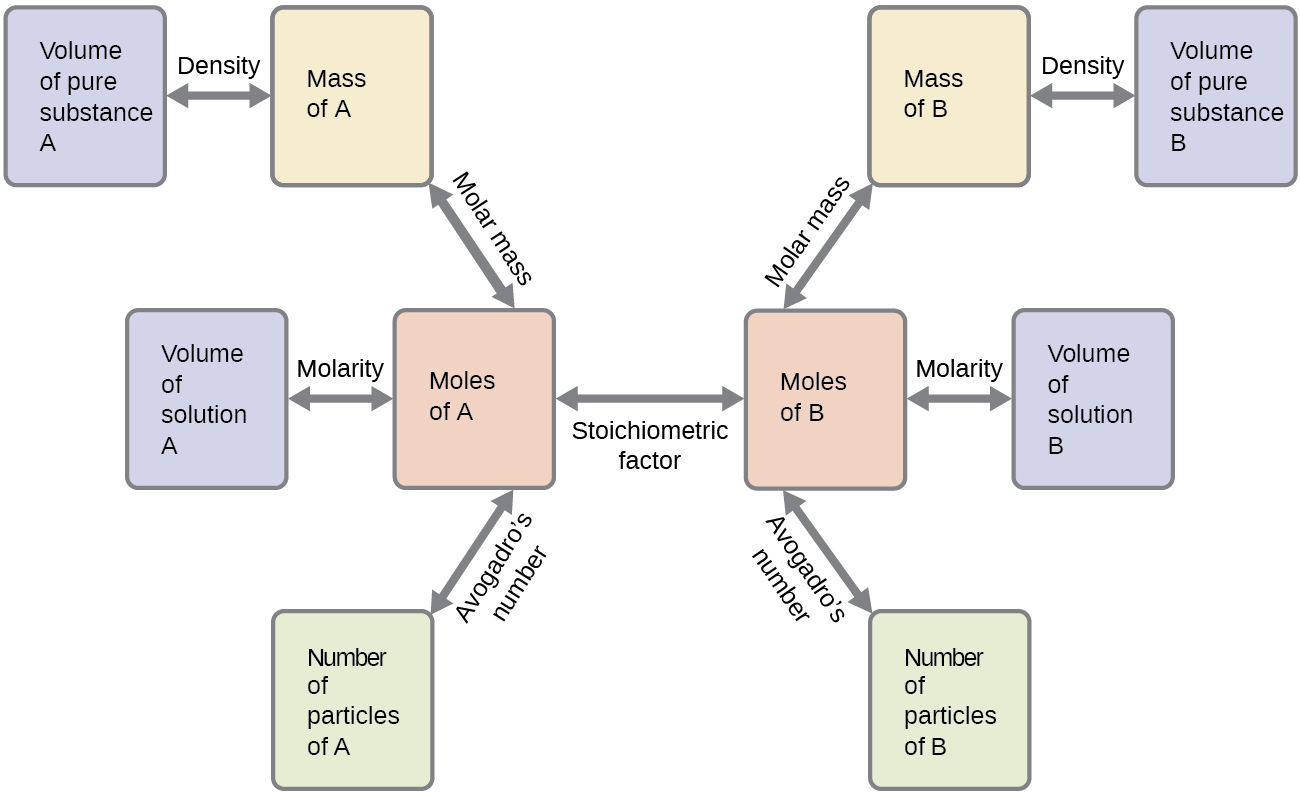

These examples illustrate just a few instances of reaction stoichiometry calculations. Numerous variations on the beginning and ending computational steps are possible depending upon what particular quantities are provided and sought (volumes, solution concentrations, and so forth). Regardless of the details, all these calculations share a common essential component: the use of stoichiometric factors derived from balanced chemical equations. Figure 2 provides a general outline of the various computational steps associated with many reaction stoichiometry calculations.

Airbags

Airbags (Figure 3) are a safety feature provided in most automobiles since the 1990s. The effective operation of an airbag requires that it be rapidly inflated with an appropriate amount (volume) of gas when the vehicle is involved in a collision. This requirement is satisfied in many automotive airbag systems through use of explosive chemical reactions, one common choice being the decomposition of sodium azide, NaN3. When sensors in the vehicle detect a collision, an electrical current is passed through a carefully measured amount of NaN3 to initiate its decomposition:

This reaction is very rapid, generating gaseous nitrogen that can deploy and fully inflate a typical airbag in a fraction of a second (~0.03–0.1 s). Among many engineering considerations, the amount of sodium azide used must be appropriate for generating enough nitrogen gas to fully inflate the air bag and ensure its proper function. For example, a small mass (~100 g) of NaN3 will generate approximately 50 L of N2.

Key Concepts and Summary

A balanced chemical equation may be used to describe a reaction’s stoichiometry (the relationships between amounts of reactants and products). Coefficients from the equation are used to derive stoichiometric factors that subsequently may be used for computations relating reactant and product masses, molar amounts, and other quantitative properties.

Chemistry End of Chapter Exercises

- Write the balanced equation, then outline the steps necessary to determine the information requested in each of the following:

(a) The number of moles and the mass of chlorine, Cl2, required to react with 10.0 g of sodium metal, Na, to produce sodium chloride, NaCl.

(b) The number of moles and the mass of oxygen formed by the decomposition of 1.252 g of mercury(II) oxide.

(c) The number of moles and the mass of sodium nitrate, NaNO3, required to produce 128 g of oxygen. (NaNO2 is the other product.)

(d) The number of moles and the mass of carbon dioxide formed by the combustion of 20.0 kg of carbon in an excess of oxygen.

(e) The number of moles and the mass of copper(II) carbonate needed to produce 1.500 kg of copper(II) oxide. (CO2 is the other product.)

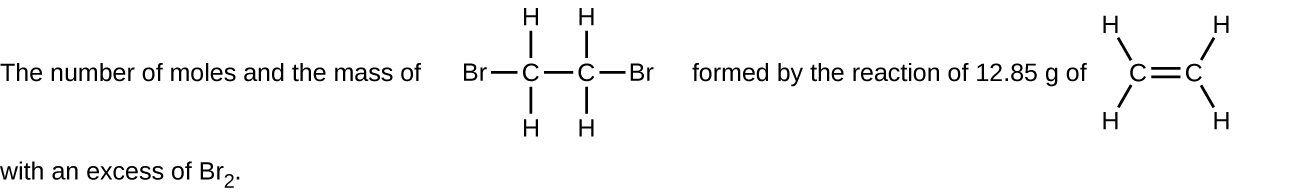

(f)

- Determine the number of moles and the mass requested for each reaction in Chemistry End of Chapter Exercise 1.

- Write the balanced equation, then outline the steps necessary to determine the information requested in each of the following:

(a) The number of moles and the mass of Mg required to react with 5.00 g of HCl and produce MgCl2 and H2.

(b) The number of moles and the mass of oxygen formed by the decomposition of 1.252 g of silver(I) oxide.

(c) The number of moles and the mass of magnesium carbonate, MgCO3, required to produce 283 g of carbon dioxide. (MgO is the other product.)

(d) The number of moles and the mass of water formed by the combustion of 20.0 kg of acetylene, C2H2, in an excess of oxygen.

(e) The number of moles and the mass of barium peroxide, BaO2, needed to produce 2.500 kg of barium oxide, BaO (O2 is the other product.)

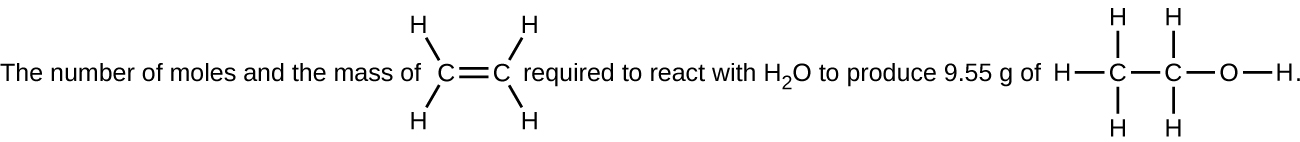

(f)

- Determine the number of moles and the mass requested for each reaction in Chemistry End of Chapter Exercise 3.

- H2 is produced by the reaction of 118.5 mL of a 0.8775-M solution of H3PO4 according to the following equation: [latex]2\text{Cr} + 2\text{H}_3 \text{PO}_4 \longrightarrow 3\text{H}_2 + 2\text{CrPO}_4[/latex].

(a) Outline the steps necessary to determine the number of moles and mass of H2.

(b) Perform the calculations outlined.

- Gallium chloride is formed by the reaction of 2.6 L of a 1.44 M solution of HCl according to the following equation: [latex]2\text{Ga} + 6\text{HCl} \longrightarrow 2\text{GaCl}_3 + 3\text{H}_2[/latex].

(a) Outline the steps necessary to determine the number of moles and mass of gallium chloride.

(b) Perform the calculations outlined.

- I2 is produced by the reaction of 0.4235 mol of CuCl2 according to the following equation: [latex]2\text{CuCl}_2 + 4\text{KI} \longrightarrow 2\text{CuI} + 4\text{KCl} + \text{I}_2[/latex].

(a) How many molecules of I2 are produced?

(b) What mass of I2 is produced?

- Silver is often extracted from ores such as K[Ag(CN)2] and then recovered by the reaction

[latex]2 \text{K} [\text{Ag(CN)}_2](aq) + \text{Zn}(s) \longrightarrow 2\text{Ag}(s) + \text{Zn(CN)}_2(aq) + 2\text{KCN}(aq)[/latex](a) How many molecules of Zn(CN)2 are produced by the reaction of 35.27 g of K[Ag(CN)2]?

(b) What mass of Zn(CN)2 is produced?

- What mass of silver oxide, Ag2O, is required to produce 25.0 g of silver sulfadiazine, AgC10H9N4SO2, from the reaction of silver oxide and sulfadiazine?

[latex]2\text{C}_{10} \text{H}_{10} \text{N}_4 \text{SO}_2 + \text{Ag}_2 \text{O} \longrightarrow 2\text{Ag} \text{C}_{10} \text{H}_{9} \text{N}_4 \text{SO}_2 + \text{H}_2 \text{O}[/latex] - Carborundum is silicon carbide, SiC, a very hard material used as an abrasive on sandpaper and in other applications. It is prepared by the reaction of pure sand, SiO2, with carbon at high temperature. Carbon monoxide, CO, is the other product of this reaction. Write the balanced equation for the reaction, and calculate how much SiO2 is required to produce 3.00 kg of SiC.

- Automotive air bags inflate when a sample of sodium azide, NaN3, is very rapidly decomposed.

[latex]2\text{NaN}_3(s) \longrightarrow 2\text{Na}(s) + 3\text{N}_2(g)[/latex]What mass of sodium azide is required to produce 2.6 ft3 (73.6 L) of nitrogen gas with a density of 1.25 g/L?

- Urea, CO(NH2)2, is manufactured on a large scale for use in producing urea-formaldehyde plastics and as a fertilizer. What is the maximum mass of urea that can be manufactured from the CO2 produced by combustion of 1.00×103kg1.00×103kg of carbon followed by the reaction?

[latex]\text{CO}_2(g) + 2\text{NH}_3(g) \longrightarrow {\text{CO(NH}_2})_2(s) + \text{H}_2 \text{O}(l)[/latex] - In an accident, a solution containing 2.5 kg of nitric acid was spilled. Two kilograms of Na2CO3 was quickly spread on the area and CO2 was released by the reaction. Was sufficient Na2CO3 used to neutralize all of the acid?

- A compact car gets 37.5 miles per gallon on the highway. If gasoline contains 84.2% carbon by mass and has a density of 0.8205 g/mL, determine the mass of carbon dioxide produced during a 500-mile trip (3.785 liters per gallon).

- What volume of 0.750 M hydrochloric acid solution can be prepared from the HCl produced by the reaction of 25.0 g of NaCl with excess sulfuric acid?[latex]\text{NaCl}(s) + \text{H}_2 \text{SO}_4(l) \longrightarrow \text{HCl}(g) + \text{NaHSO}_4(s)[/latex]

- What volume of a 0.2089 M KI solution contains enough KI to react exactly with the Cu(NO3)2 in 43.88 mL of a 0.3842 M solution of Cu(NO3)2?[latex]2 \text{Cu(NO}_3)_2 + 4\text{KI} \longrightarrow 2\text{CuI} + \text{I}_2 + 4{\text{KNO}_3}[/latex]

- A mordant is a substance that combines with a dye to produce a stable fixed color in a dyed fabric. Calcium acetate is used as a mordant. It is prepared by the reaction of acetic acid with calcium hydroxide.[latex]2\text{CH}_3 \text{CO}_2 \text{H} + \text{Ca(OH)}_2 \longrightarrow \text{Ca(CH}_3 \text{CO}_2)_2 + 2\text{H}_2 \text{O}[/latex]

What mass of Ca(OH)2 is required to react with the acetic acid in 25.0 mL of a solution having a density of 1.065 g/mL and containing 58.0% acetic acid by mass?

- The toxic pigment called white lead, Pb3(OH)2(CO3)2, has been replaced in white paints by rutile, TiO2. How much rutile (g) can be prepared from 379 g of an ore that contains 88.3% ilmenite (FeTiO3) by mass?[latex]2\text{FeTiO}_3 + 4\text{HCl} + \text{Cl}_2 \longrightarrow 2\text{FeCl}_3 + 2\text{TiO}_2 + 2\text{H}_2 \text{O}[/latex]

Glossary

- stoichiometric factor

- ratio of coefficients in a balanced chemical equation, used in computations relating amounts of reactants and products

- stoichiometry

- relationships between the amounts of reactants and products of a chemical reaction

Solutions

Answers to Chemistry End of Chapter Exercises

2. (a) 0.435 mol Na, 0.217 mol Cl2, 15.4 g Cl2; (b) 0.005780 mol HgO, 2.890 × 10−3 mol O2, 9.248 × 10−2 g O2; (c) 8.00 mol NaNO3, 6.8 × 102 g NaNO3; (d) 1665 mol CO2, 73.3 kg CO2; (e) 18.86 mol CuO, 2.330 kg CuCO3; (f) 0.4580 mol C2H4Br2, 86.05 g C2H4Br2

4. (a) 0.0686 mol Mg, 1.67 g Mg; (b) 2.701 × 10−3 mol O2, 0.08644 g O2; (c) 6.43 mol MgCO3, 542 g MgCO3 (d) 713 mol H2O, 12.8 kg H2O; (e) 16.31 mol BaO2, 2762 g BaO2; (f) 0.207 mol C2H4, 5.81 g C2H4

6. (a) [latex]\text{volume HCl solution} \longrightarrow \text{mol HCl} \longrightarrow \text{mol GaCl}_3[/latex]; (b) 1.25 mol GaCl3, 2.2 × 102 g GaCl3

8. (a) 5.337 × 1022 molecules; (b) 10.41 g Zn(CN)2

10. [latex]\text{SiO}_2 + 3\text{C} \longrightarrow \text{SiC} + 2\text{CO}[/latex], 4.50 kg SiO2

12. 5.00 × 103 kg

14. 1.28 × 105 g CO2

16. 161.40 mL KI solution

18. 176 g TiO2

Feedback/Errata