7 How to Play: Ideation and Prototyping

Challenge Assumptions

It’s not stupid at all to ask so-called stupid questions which help us challenge status quo. There are many ways we get stuck into patterns of thinking and doing, making innovation difficult. It’s easy to keep doing things the way they’ve always been done, and to be comfortable with keeping things that way. Change can be scary and challenging to grapple with, though it is something we need to become increasingly comfortable with, considering the rapidly changing environments we find ourselves in.

Some of the most established characteristics of products, services, business models, environments are subject to change at any given time. Not too long ago, the following questions were quite thought-provoking, and some would call the questions downright stupid: Do doors always have to have handles? Should taps always be hand-operated? Do cars have to have a driver and a steering wheel?

The new frontier of innovation is smashing assumptions we have about how things should be and coming up with disruptive ways of arriving at the same goals in ways we never considered possible.

When

Take a step back from the challenge you’re tackling and ask some important questions about the assumptions you have about the product, service, or situation where you’re trying to innovate.

Challenging assumptions when you are stuck in current thinking paradigms or when you have run out of ideas is particularly effective. Therefore, it is good for rebooting a flagging session.

How

List Assumptions

Remember that everything is a perspective.

Typical Assumptions Include…

- That it is impossible to do something—particularly within constraints such as time and cost.

- That something works because of certain rules or conditions.

- That people believe, think, or need certain things.

Challenge Assumptions

Assume that you can overcome and challenge all

assumptions.

Ask questions like: ‘How could this be not true?’ ‘What if we could do this twice as well in half the time?’ ‘Are the characteristics we take for granted about these things really crucial aspects, or are they just so because we’ve all become accustomed to them?’ ‘Do people really always have to wear identical socks on both feet, or even identical shoes, for that matter? Are socks even necessary?’ These kinds of questions may sound silly, and many of the assumption busters you may come up with may indeed be silly, until you come up with something that really makes the entire team sit up straight and say, “Hey, why call it ‘ABC’? What if it’s really ‘XYZ’?” You have to ask a few dumb questions before you reach the insightful ones, as Don Norman likes to put it. It’s not that any of the questions are really dumb, though; it’s just that it takes some experimentation before a different yet viable way of looking at things rears its head.

Find ways of making the challenge a reality. The real challenge is to make it happen in reality. Use this very same principle again.

Brainstorming – 8 Rules

Brainstorming is a great way to generate a lot of ideas that you would not be able to generate by just sitting down with a pen and paper. The intention of brainstorming is to leverage the collective thinking of the group, by engaging with each other, listening, and building on other ideas. Conducting a brainstorm also creates a distinct segment of time when you intentionally turn up the generative part of your brain and turn down the evaluative part. Brainstorming is the most frequently practiced form of ideation. Here, you’ll learn the best practices from the very best experts from d.school and IDEO as well of the father of the Brainstorming technique, Alex Osborn. The following are some rules, principles, and suggestions so you can make brainstorming sessions much more user-oriented, effective, innovative—and fun.

The Rules

Set a time limit

d.school emphasizes setting aside a period when your team will be in “brainstorm mode.” In this time frame, it’s the sole goal to come up with as many ideas as possible, and during this period judgement of those ideas are prohibited.

Start with a problem statement

Start with a Point of View, How Might We questions, a plan or a goal—and stay focused on the topic. Alex Osborn, the father of the Brainstorming technique, emphasizes that brainstorming sessions should always address a specific question or problem statement (also called a Point of View) as sessions addressing multiple questions are inefficient.

Defer judgement

A Brainstorming session is not the time and the place to evaluate ideas. It’s crucial that participants are feeling confident by being in a safe environment so they have no fear of being judged by others when they put forward wild ideas. The best ideas often come from practitioners, students, and people who dare to think differently.

Encourage weird, wacky, and wild ideas

These new ways of thinking might give you better solutions. Suspend judgement and feel free to generate unusual ideas. You’ll be surprised to see how effective this tool is and how it helps open up minds and creates a collaborative, curious, and friendly ideation environment.

Aim for quantity

Aim for as many new ideas as possible. The assumption is that the greater the number of ideas you generate, the bigger your chance is of producing a radical and effective solution. Brainstorming celebrates the maxim “quantity breeds quality.”

Build on each others’ ideas

As suggested by the slogan “1 + 1 =3,” Brainstorming stimulates the building of ideas by a process of association. Embrace the most out-of-the-box notions and build, build, build. Be positive and build on the ideas of others. Brainstorming works well when participants use each other’s ideas to trigger their own thinking. Our minds are highly associative. One thought easily triggers another.

Be visual

At IDEO, they encourage you to use colored markers to write on Post-its and put them on the wall—or sketch your idea. Nothing gets an idea across faster than drawing it. It doesn’t matter how terrible of a sketcher you are! It’s all about the idea behind your sketch.

One conversation at a time

Listen to each other and elaborate on each other’s ideas. Don’t get obsessed with your own ideas. You’re here to ideate together. When all team members have presented their ideas, you can select the best ideas, which you can continue to build and elaborate on in other ideation sessions.

Brainwrite (Teams)

Brainwriting is a technique where participants write ideas onto cards and then pass their idea cards on to the next person, moving those cards around the group in a circle as participants build on the ideas of others. Participants perform this technique in complete silence—and they are forced to build on, instead of criticize, other participants’ ideas. The cycle can be repeated multiple times and can be applied to chunks of the problem being addressed, depending on the need.

Why

The beauty of brainwriting is that it levels the playing field immediately, and it removes many of the obstacles of group brainstorming. With traditional verbal brainstorming, the number of ideas which can be expressed at once is limited, and the time it takes to get through a number of ideas is much longer, which results in many participants forgetting or becoming confused while others shout out ideas. This is especially so for those who are shy or introverted or who may be at a disadvantage due to being less senior or unfamiliar with the specializations being discussed.

Brainwriting is an excellent starting point for ideation sessions, and can serve as a means to maximise the initial braindump, or as a way to refocus if other ideation methods go haywire. Before the chaos of group ideation muddles people’s thinking, help them get their initial thoughts out in the open with an introductory brainwriting session and use the results later to build on further with other techniques.

Best Practice: How

- Review the problem statement, goals and important user insights from previous research and findings.

- Participants to jot down ideas on their idea cards for 3-5 minutes before passing on their ideas when you make the call.

- Ideally, participants pass on idea cards 3-1 O times depending on the problem statement and goals.This all happens silently and without any interference or communication.

- Participants should to push themselves for more ideas at least a couple of times, in the few minutes they have, in order to maximize the output and variation.

- Keep the session positive and provide questions or statements which push participants to think outside of their comfort zones.

- The cycle can be repeated multiple times and can be applied to chunks of the problem being addressed, depending on the need.

- After ending the cycle, each participant will briefly verbally present the thoughts on the idea card he or she ends up with by the end of the cycle to the rest of the team-in order to spark new streams of thinking or combinations of ideas. A volunteer should take notes on a white board to keep things visual.

- When all team members have presented their idea cards, the team can select the best ideas which they can continue to build and elaborate on in other ideation sessions.

Braindump (Individual)

Brainstorming (group sessions) has three siblings which you should get to know: braindumping (individual sessions), brainwriting (a mix of individual and group sessions) and brainwalking (another mix of individual and group sessions).

Should Your Team Brainstorm as a Group or as Individuals?

Switching between the two modes of individual and collective ideation sessions can be seamless and highly productive. Alex Osborn’s 1950s classic Applied Imagination gave advice that is still relevant: Creativity comes from a blend of individual and collective ideation.

It’s often a good idea to do individual ideation sessions like braindumping, brainwriting and brainwalking before and after brainstorming group sessions. We recommend that you mix the methods: brainstorming, brainwriting, brainwalking, and braindumping.

Why

One of the best ways to progress to more advanced levels of ideation is to start by getting everything that’s currently clogging the neural pathways out in the open and freeing up some cognitive space for other synapses, connections, and mixtures to get through. David Allen, author of the world famous “Getting Things Done” methodology, swears by the braindump as a means to free up mental energy and allow freethinking. Holding onto your own thoughts, unfinished tasks, or unexplored ideas creates mental blockages and prevents freethinking. Furthermore, braindump is an amazing technique to help quiet employees get a voice.

Best Practice: How

- If you were the facilitator, you’ll brief ideation participants upfront on the problem statement, goals and important insights from previous research and findings.

- Then ask all participants to write down their ideas as they come. It’s important that each participant does this individually—and silently.

- Provide participants with sheets of paper, idea cards or traditional Post-it notes. Sticky notes are great, because they allow people to write their ideas down individually—one idea per note.

- Give participants between 3 and 10 minutes to get ideas they have been thinking of off their chests.

- After reaching the time limit of approximately 3-1 minutes, each participant will say a few words about his or her ideas and stick them on a board or wall. You should avoid initial discussions about notes when team members are presenting them. Ideas that come out of early braindump sessions should be shared verbally with the entire team in order to spark new streams of thinking or combinations of ideas.

- While sticking the ideas up and presenting them, the group will also group duplicates together.

- When all team members have presented their ideas, you can select the best ideas, which you can continue to build and elaborate on in other ideation sessions. There are various methods you can use such as “Post-it Voting,” “Four Categories,” “Bingo Selection,” “Six Thinking Hats,” and “Now Wow How Matrix.”

Idea Selection

At some point in your ideation sessions, you’ll have reached a critical mass of ideas, and it will become unproductive to attempt to keep pushing for more. This is different from the natural creative slumps that teams experience throughout ideation sessions, and means it is a good point to stop and focus on pruning. This is referred to as the ‘convergent stage’ where ideas are evaluated, compared, ranked, clustered and even ditched in an attempt to pull together a few great ideas to act on. Hang onto those unused ideas, though; they may prove useful in future ideation sessions as stokers or idea triggers. Right now, the aim is spotting potential winners, or combinations of winning attributes, from a number of ideas.

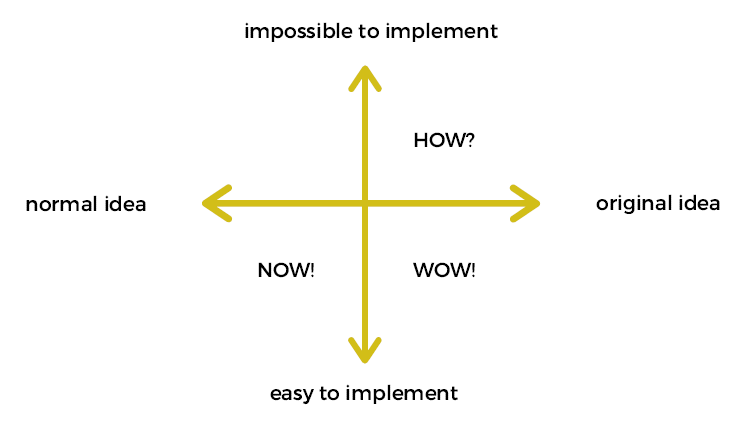

Now Wow How Matrix

Split ideas according to a variety of form factors, such as their potential applications in:

- Now: ideas that can be implemented immediately but which lack novelty.

- Wow: ideas that can be implemented and are innovative.

- How: ideas that could possibly be implemented in the future.

Your Now Wow How Matrix should contain two axes, with the vertical representing difficulty of implementation and the horizontal axis representing the degree of innovation. This provides an easy-to-follow formula for evaluating the viability of ideas as well as their innovativeness.

Bingo Selection

The Bingo Selection method inspires participants to divide ideas: The facilitator should encourage the participants to split ideas according to a variety of form factors, such as their potential applications in: A physical prototype, a digital prototype, and an experience prototype.

- Ideation participants decide upon one or two ideas for each of these categories.

- If you’re a relatively small team you simply discuss the pros and cons of the chosen ideas.

- If you’re a large team you can mix this method with Post-it Voting (also known as Dot Voting).

- Write all of the ideas which the participants have chosen on individual Post-its.

- Then you give all participants a number of votes (around three to four should do) to choose and write down their personal favorite ideas.

- Participants vote by using stickers or simply using a marker to make a dot on the ideas they like. This process allows every member to have an equal say in the shortlisted ideas.

- You can also use variations in color in order to let participants vote on which ideas they like the most or which they dislike the most.

- You can invent other voting attributes when it makes sense.

Four Categories Method

At some point in your ideation sessions, you’ll have reached a critical mass of ideas, and it will become unproductive to attempt to keep pushing for more. This is referred to as the ‘convergent stage’ where ideas are evaluated, compared, ranked, clustered and even ditched in an attempt to pull together a few great ideas to act on. Right now, the aim is spotting potential winners, or combinations of winning attributes, from a number of ideas.

The Four Categories method entails dividing ideas according to their relative abstractness, ranging from the most rational choice to the ‘long shot.’ The four categories are: the rational choice, the most likely to delight, the darling, and the long shot. This method ensures that the team covers all grounds, from the most practical to the ideas with the most potential to deliver innovative solutions.

Ideation participants decide upon one or two ideas for each of these categories: the rational choice, the most likely to delight, the darling, and the long shot.

Six Thinking Hats

The Six Thinking Hats will help you apply the idea criteria which are right for your current design challenge. These methods will help you work through the pile of ideas which you’ve generated and select the best ones, which you can start prototyping and testing.

The Six Thinking Hats Technique provides a range of thinking styles to apply to idea selection.

The participants should evaluate and consider all the ideas through six various mindsets and thinking styles so as to uncover the widest range of possible angles on the ideas being assessed.

White Hat: The White Hat calls for information which is known or needed. It’s all about this: ‘The facts, and nothing but the facts.’

Yellow Hat: The Yellow Hat symbolizes optimism, confidence, and brightness. Under this hat, you explore the positives and probe for value and benefit.

Black Hat: The Black Hat is all about judgement. When you put on this hat, you’re the devil’s advocate, where you try to figure out what or why something may not work.

Red Hat: The Red Hat calls for feelings, hunches, and intuition. When you use this hat, you should focus on expressing emotions and feelings and share fears, likes, dislikes, loves, and hates.

Green Hat: The Green Hat focuses on creativity: the possibilities, alternatives, and new ideas. It’s your opportunity to express new concepts and new insights.

Blue Hat: The Blue Hat is used to manage the thinking process. It’s your control mechanism that ensures the Six Thinking Hats guidelines are observed.

Prototyping for Empathy

While you will create most prototypes in order to evaluate the ideas that your team has come up with, it is also possible to use prototypes to develop empathy with your users, even when you do not have a specific product in mind to test. We call this “prototyping for empathy” or “active empathy.”

When

Use empathy prototypes to gain an understanding of the problem as well as your users’ mindsets about pertinent issues. You will find that using empathy prototypes is best after you have some basic research and understanding of the design problem and users.

Why

Empathy prototypes are extremely useful in helping you probe deeper into certain issues or areas.

Best Practice

- The first thing to do is to determine what it is you want to test: Before building an empathy prototype you will need to figure out what aspects of a user or the environment you would like to probe deeper.

- Then, build prototypes that will effectively evaluate those aspects. For instance, if you want to find out about your users’ mindsets towards reading, you could ask your users to draw how they think about reading. After they have finished, you could ask them about what they have drawn and—from there—understand how they think.

- Alternatively, you could create an empathy prototype for yourself and your teammates so as to help you step into your users’ shoes. If you are building prototypes for people with visual impairments, such as the elderly, you could create a quick prototype by applying some gel onto a pair of lightly tinted sunglasses. Wearing this prototype would simulate the poor eyesight of the elderly and enable you to gain an idea of the obstacles they face.

- Sort out the logistics. What do you need? For example: physical space, sunglasses, pen, paper, permits, additional staff, or anything else?

- Consider if it would be an advantage to run a few empathy prototype tests at once in order to test different aspects of a user and or environment. This will allow you to test a variety of assumptions and ideas quickly.

- You should continuously capture all relevant feedback from the people you’re designing for.

- Gathering feedback from prototyping sessions can feel like a haphazard process.

- Continue to iterate. Continue to learn, adapt, create new prototypes, and test them.

Prototype to Decide

Sometimes in your design project, you may face conflicting ideas from different team-mates or stakeholders. Prototyping can be an effective tool for enabling your team to compare the ideas and prevent any disagreements from developing.

When building a prototype to decide, you can see how each of the solutions will work better. You will be able to see whether the prototypes lack in some areas; for example, you may realize that the prototype would not work in the natural environment of users. Your team will also be able to see the different ideas tangibly, and hence discuss the ideas and build on them, or suggest ways to merge the best aspects of each prototype.

Best Practice

- Decide what it is you want to test.

- Then, build (preferably low-fidelity) prototypes that will effectively evaluate those aspects by testing your prototype with real users.

- Sort out the logistics. What do you need? For example: physical space, sunglasses, pen, paper, permits, additional staff, or anything else?

- Consider if it would be an advantage to run a few prototype tests at once in order to test different aspects of a user or the environment.

- Present the prototypes.

- You should continuously capture all relevant feedback to provide you with sufficient feedback for moving on in the design process.

- Prototyping is an effective tool for enabling your stakeholders and team members to compare your ideas and prevent any disagreements from developing. It’s now time to decide.

- Gather feedback.

- Continue to iterate. Continue to learn, adapt, create new prototypes, and test them.

Prototype to Decide

This will be the most common prototype you will create in a design project. Create iteratively improved prototypes in order to test out solutions quickly, and then use the test results to improve your ideas.

Best Practice

- Decide what it is you want to test: So as to start with prototyping to test, you will first need to identify the key question(s) you want to answer through your prototype. That way, you can focus on building the aspects of the prototype that test these questions, thereby saving time and allowing you to pursue various ideas at the same time.

- While prototyping, keep in mind how you will test the prototype. Figure out if you will need to test the prototype in the natural environment of the user (chances are, the answer is “yes”). If that is not possible, determine how best to simulate the natural environment.

- Then, build prototypes that will effectively evaluate those aspects by testing your prototype with real users.

- Consider if it would be an advantage to run a few prototype tests at once in order to test different aspects of a user or the environment. This will allow you to test a variety of ideas quickly.

- Present and test the prototypes.

- You should continuously capture all relevant feedback to provide you with sufficient feedback for moving on in the design process.

- Gathering feedback from testing sessions can feel like a haphazard process.

- Continue to iterate. Continue to learn, adapt, create new prototypes, and test them.