Chapter 1: Wright’s Life and Career

Organic Architecture (Lindsay Wells and John Hallett)

Lindsay Wells and John Hallett

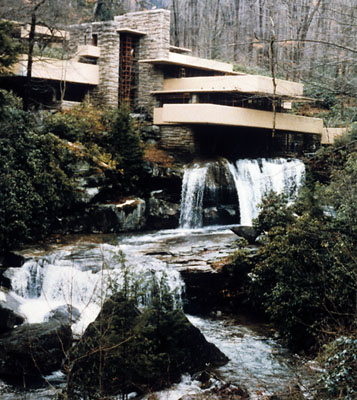

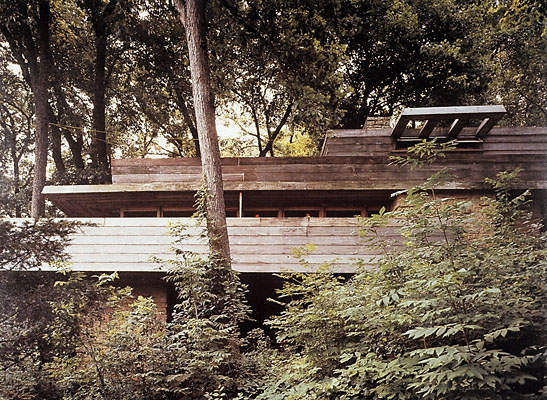

From the dramatic coastal views found at Graycliff (1926-31) and Walker House (1948) to the hydraulic features incorporated into Taliesin (1911) and Storer House (1923), aquatic elements are as recognizable hallmarks of Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture as his clean horizontal rooflines, rough-cut masonry, and bright, open floor plans. Encountering the words “Wright” and “water” in the same sentence will most likely bring to mind the iconic Kaufmann House in Bear Run, Pennsylvania—more commonly known as Fallingwater (1934-37). This famous American landmark, cantilevered over a series of small waterfalls, inspired the design of a slightly later Wright home in Madison, Wisconsin known as the Pew House (1938-40), or, “Little Fallingwater.”[1] Many of Wright’s projects that respond to the features of their surrounding landscapes are often categorized as examples of his organic architecture. [Figures 1 and 2]

Wright’s philosophy of organic architecture was broad ranging. It encompassed site specificity, the inclusion of natural and native materials, an emphasis on truth to materials and cohesive interior decorating, ideally coordinated through an overarching holistic design, “perfect correlation, integration is life.”[2] Overall, there was an intense focus on integrating a building with its surroundings, such as the enveloping trees found around Wright’s own house in Oak Park, the Isabel Roberts House, and, eventually, the Pew House. Wright also found it necessity to harmonize furnishings, artwork, and even music into a congruous architectural whole. In Wright’s opinion, all ornament must serve a clear and complimentary purpose within a structure.[3] For example, Wright-designed furnishings were successfully incorporated into Madison’s Unitarian Meeting House, where custom-built moveable tables enhance the function of a multi-use auditorium.

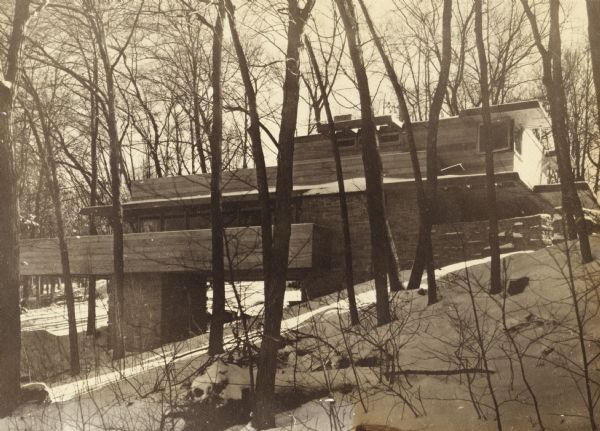

The somewhat arbitrary—and contradictory—nature of Wright’s simultaneous manipulation and retention of a building site’s topography becomes apparent through a comparison of the Lamp and Pew Houses’ different relationships to Lake Mendota. The ground beneath the Lamp House was artificially elevated to afford lake views that were not possible on the original site.[4] By contrast, the Pew House site was altered minimally, demonstrating a different kind of respect for the natural state of the building’s environment.[5] [Figure 3] It appears that Wright’s principles of organic architecture, like all design criteria, were compromised on occasion to satisfy the limitations of design briefs and budgets.

According to Wright, “The ideal of an organic architecture…is a sentient, rational building that would owe its ‘style’ to the integrity with which it was individually fashioned to serve its particular purpose—a ‘thinking’ as well as ’feeling’ process.”[6] In his treatise The Natural House (1954), Wright further clarified his opinions on nature and architecture. Forty years after his first use of the phrase ‘organic architecture’, Wright defined its aim as follows: “To be a natural performance, one that is integral to site; integral to environment; integral to the life of the inhabitants.”[7] Overall, the themes of balance, integration, harmony, and vitality emerge in many Wright buildings, from modest dwellings such as Pew House to some of his most celebrated projects, such as Fallingwater. [Figure 4]

Works Cited

Image Sources

Figure 1: http://images.library.wisc.edu.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/ArtHistory/S/63/t/236691t.jpg

Figure 2: http://images.library.wisc.edu.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/ArtHistory/S/136/t/262995t.jpg

Figure 3: http://images.library.wisc.edu.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/ArtHistory/S/63/t/245663t.jpg

Figure 4: http://wisconsinhistory.org

- 1. Neil Levine, “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Diagonal Planning Revisited,” in On and By Frank Lloyd Wright: A Primer of Architectural Principles, ed. Robert McCarter (London: Phaidon Press, 2005), 253. ↵

- 1. Frank Lloyd Wright, “Organic Architecture,” in The Natural House (New York: Horizon Press, 1954), 22. ↵

- 1. Frank Lloyd Wright, “Organic Architecture,” in The Natural House (New York: Horizon Press, 1954), 26. ↵

- 1. Erin Abler, “A Hidden History: Frank Lloyd Wright & The Robert M. Lamp House,” Madison Originals Magazine, 2013, 19. ↵

- 1. Peter A. Rött, “Sustaining Wright 101,” Save Wright 2 (Fall 2011): 9. ↵

- 1. Frank Lloyd Wright, In the Cause of Architecture: Essays by Frank Lloyd Wright for the Architectural Record, 1908-1952., ed. Frederick Gutheim (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1975), 6. ↵

- 1. Frank Lloyd Wright, The Natural House (New York: Horizon Press, 1954), 134. ↵