The Pew House (1937)

Pew House (1937)

Lindsay Wells and John Hallett

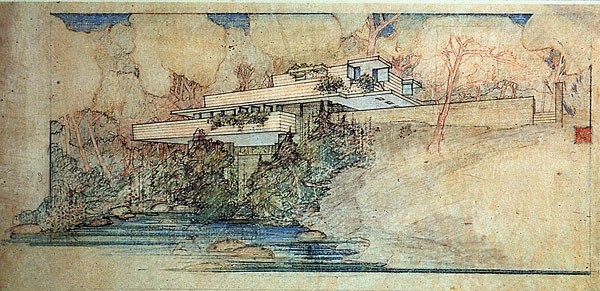

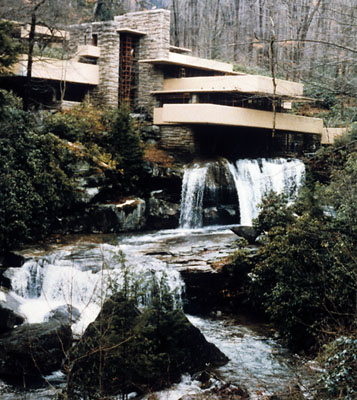

The John and Ruth Pew House is a private, single-family residence located along the shores of Lake Mendota in the Shorewood Hills neighborhood of Madison, Wisconsin. It was commissioned in 1837 and built by Frank Lloyd Wright between 1938 and 1940, only a few years after the completion of his famous commission of Fallingwater in Bear Run, Pennsylvania (and to which the Pew’s home is often compared). The Pew House sits atop a small ravine that runs directly into the lake, thus facilitating a close relationship between the house and its natural surroundings. [Figure 1] With its site-specific structural innovations and comprehensive use of local materials, the Pew House stands as a quintessential expression of Wright’s concept of organic architecture.

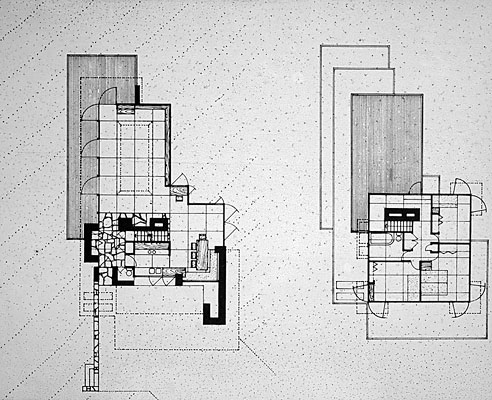

Initially planned as a colonial-style dwelling, the commission for the Pew House eventually fell into the lap of Herbert Fritz, a young disciple of Wright’s and future Taliesin fellow. He quickly sent the Pews to Wright himself, who enlisted the help of his assistants at Taliesin to draw structural plans for the building based on surveys of the lot in Shorewood Hills. [Figure 2] William Wesley Peters and C.W. Caraway spearheaded the construction of the house as its on-site supervisors. Fritz also helped see the project through to its completion in November of 1940.[1]

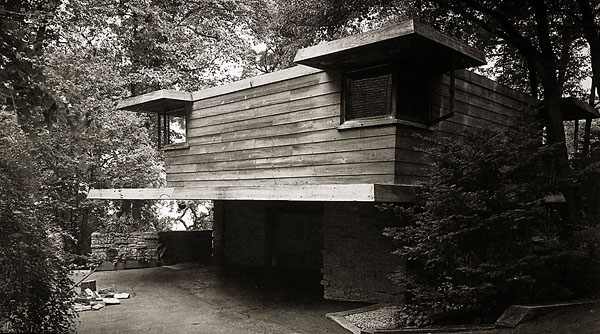

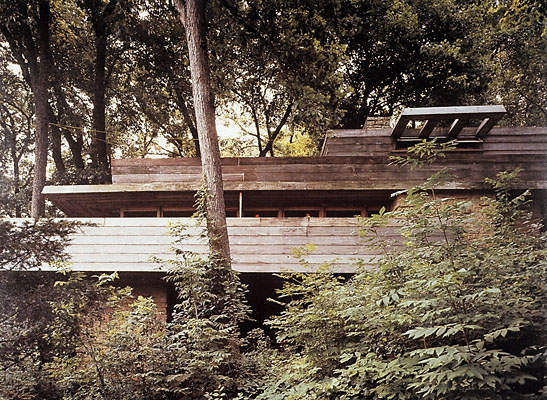

The resultant 1,791 square-foot, two-story home—which has been little altered over the past 70 years—consists of an open living room with stone fireplace, a galley kitchen, a washroom, and a dining area on its ground level. There are also three bedrooms, one bathroom, and a linen closet located upstairs. [Figure 3] A large wooden balcony wraps around the exterior of the first story. Approaching from the road to the south, one can observe the home’s attached carport. [Figure 4] The carport and second-story corner roof eaves form a diamond-shaped point at the base of the driveway. This masks the otherwise strong horizontality of the structure, which is more clearly visible from the lakeshore.[2] [Figure 5] The house itself sits 70 feet back from the water’s edge at a 45-degree angle to the property line, which affords panoramic views of Lake Mendota both from inside the north-facing living room and from its L-shaped exterior balcony.[3]

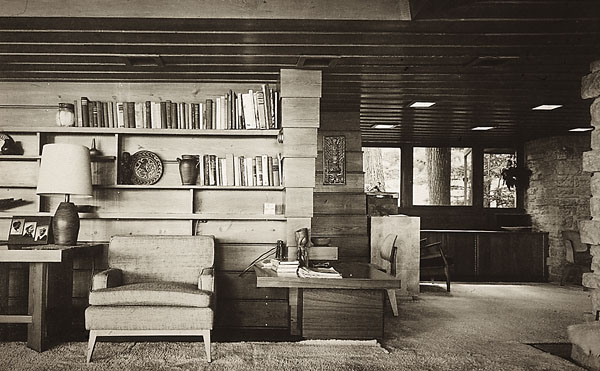

Two-thirds of this rectangular living space are cantilevered on limestone piers across a shallow gully that carries runoff from nearby hills into the lake. [Figure 6] A stone watercourse located beneath the house helps prevent erosion to the site.[4] Although it is flanked by neighboring homes, the surrounding lot is heavily wooded with cypress, linden, and other deciduous trees and shrubs. Wright chose to construct the Pew House primarily out of local materials, in part to harmonize the structure with its forested environs. Rough-cut limestone and untreated tidewater cypress comprise the exterior walls and masonry. They also reappear throughout the interior, most noticeably in the central living room, which includes cypress wall paneling and an imposing stone hearth. [Figure 7] The house is relatively airy and bright thanks to a large ribbon of windows opening out onto the main balcony.[5] One of its most innovative features is a hidden light well located behind the kitchen cabinetry that allows sunshine to pass directly from the second story down to the ground floor.[6]

Pew House is a modestly sized residence built in Wright’s Usonian style, the main hallmark of which is a functional, cost-effective layout. The main entrance, situated around the left corner of the carport, funnels visitors directly into the spacious living area. To the north, this room gradually unfolds into the dining area and nearby galley kitchen, which shares a wall with the downstairs washroom. A sense of economy and convenience permeate the entire house. The logical organization of the building’s rooms also privileges the ease of movement. Usonian architecture grew out of a need Wright saw during the Great Depression for affordable family housing in America. John and Ruth Pew’s budget for their own home was roughly $8,500.[7] To save them money, the Taliesin fellows salvaged glass and steel building materials from nearby construction sites.[8] Wright’s Usonian style also reflects his desire to invent a uniquely American architectural aesthetic. A different Madison residence—the Herb Jacobs House—was one of Wright’s first Usonian structures in the area.[9] Like other Usonian homes, including the Jacobs House, the Pew House is heated by hot water pipes located beneath its wooden floorboards.[10] It also includes functional cabinetry throughout the ground floor, including several built-in wooden bookshelves around the living room.[11] [Figure 8]

The Pew House as an Expression of Organic Architecture

One of the definitive features of the Pew House is its reflection of Wright’s principles of organic architecture—or in other words, the thoughtful integration of a building with its natural environment. According to Wright’s 1908 treatise “In the Cause of Architecture,” “A sense of the organic is indispensable to an architect.”[12] But what exactly did Wright mean by this statement, and how specifically does the concept of organic architecture emerge in buildings such as Pew House?

Wright’s organic theories partially grew out of his early experiences working for the famous nineteenth-century architectural firm of Louis Sullivan, whose buildings were renown for their use of natural forms and decorative motifs.[13] This complemented Wright’s firm belief that structures should adhere to the inherent affordances of their building materials and building sites. Unlike some of his other private homes built in Madison, such as the Jacobs and Lamp Houses, Wright made very little alterations to the Pew House property before commencing any kind of construction work. Despite the fact that the steep elevation of the Mendota lakeshore made this a challenging property to build on, Wright and his apprentices dedicated themselves to working with, rather than against, the topography and flora of the site.[14] [Figure 9] Wright emphasized the importance of such ecologically respectful practices in his 1954 book The Natural House. Interestingly, he chose to illustrate his chapter on the role of integrity in domestic architecture with pictures of the Pew House. Here, Wright articulates the practical and aesthetic goals of such “organic” buildings:

“The Usonian house, then, aims to be a natural performance, one that is integral to site; integral to environment; integral to the life of the inhabitants. A house integral with the nature of materials—wherein glass is used as glass, stone as stone, wood as wood—and all the elements of environment go into and throughout the house.”[15]

Indeed, many of these details found their full expression in the Pew House. Arguably the most important piece of criteria for organic architecture is the use of local materials that compliment the natural features of a building site. Wright deliberately left the cypress sideboards of the Pew House’s exterior untreated, which allowed them to weather and harmonize naturally with the soft greys and browns of adjacent tree trunks.[16] The beige tints of the limestone piers and central chimney also resonate with the earth-tone palette of the site. Because the Pew House sits atop a ravine on steel-reinforced masonry, many have compared it to its famous predecessor Fallingwater, which straddles a cascading stream of waterfalls in the Pennsylvanian woods. [Figure 10] Both homes embrace the geological idiosyncrasies of their natural settings; however, it is notable that the Pew House’s cantilevered piers are made of local limestone, as opposed to the manufactured concrete used in Fallingwater.[17]

As revealed in The Natural House, Wright felt it was important that “all the elements of environment go into and throughout” a building. This integrative philosophy emerges in multiple sections of the Pew House. For example, as noted above, the same lapped cypress and horizontal stones on the exterior of the home reappear on its interior, especially in the central living area. This particular room, with its large bank of lakefront windows, prompted Wright to declare that the Pew House was “probably the only house in Madison, Wisconsin, that recognizes beautiful Lake Mendota, my boyhood lake…a house actually built by the Taliesin Fellowship.”[18] The scenic views, unvarnished carpentry, and coarse stonework of this building certainly demonstrate the visual power and continuity of Wright’s organic theories. Nevertheless, the most literal—and surprising—expression of natural harmony at the Pew House appears in its first-floor balcony, which Wright wrapped around a large linden tree growing alongside the eastern edge of the building’s foundation.[19] [Figure 11] Here, nature is literally incorporated into the structure of the Pew House, thus underscoring the importance of organic form and environment in Wright’s domestic spaces.

In conclusion, the Pew House is an important building that touches upon multiple facets of Wright’s career, from his Usonian period and Madison oeuvre to his lifelong passion for nature. Moreover, as a functional and innovative combination of water, earth, and plant life, the Pew House merits the distinction as a preeminent example of Wright’s organic architecture.

Works Cited

Grupico, Theresa. “Frank Lloyd Wright and Our Attitude Toward Nature.” The Forum on Public Policy, 2011, 1–14.

Hitchcock, Henry-Russell. In the Nature of Materials. New York: Duell, Sloan, and Pearce, 1942.

Kalec, Donald G. “The Jacobs House I.” In Frank Lloyd Wright and Madison: Eight Decades of Artistic and Social Interaction, edited by Paul E. Sprague, 91–100. Madison, WI: Elvehjem Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1990.

“Pew House Exemplifies Wright’s Principles.” Wisconsin State Journal. February 19, 1995.

“Pew House File #0910.” Isthmus Architecture Inc., n.d. Accessed April 29, 2016.

Rött, Peter A. “Sustaining Wright 101.” Save Wright 2 (Fall 2011): 8–11.

Sergeant, John. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian Houses: Designs for Moderate Cost One-Family Homes. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1976.

Sprague, Paul E., and Diane Filipowicz. “The Pew House.” In Frank Lloyd Wright and Madison: Eight Decades of Artistic and Social Interaction, edited by Paul E. Sprague, 109–13. Madison, WI: Elvehjem Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1990.

Wright, Frank Lloyd. “In the Cause of Architecture.” Art Humanities Primary Source Reading 51, 1908.

———. The Natural House. New York: Horizon Press, 1954.

Image Sources

Figure 1: http://images.library.wisc.edu.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/ArtHistory/S/63/t/236691t.jpg

Figure 2: http://images.library.wisc.edu.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/ArtHistory/S/63/r/217592r.jpg

Figure 3: http://images.library.wisc.edu.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/ArtHistory/S/64/r/236113r.jpg

Figure 4: http://images.library.wisc.edu.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/ArtHistory/S/63/r/245609r.jpg

Figure 5: http://images.library.wisc.edu.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/ArtHistory/S/63/t/245663t.jpg

Figure 6: http://images.library.wisc.edu.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/ArtHistory/S/63/r/236692r.jpg

Figure 7: http://images.library.wisc.edu.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/ArtHistory/S/63/r/245611r.jpg

Figure 8: http://images.library.wisc.edu.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/ArtHistory/S/63/r/245612r.jpg

Figure 9: http://images.library.wisc.edu.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/ArtHistory/S/64/r/18073r.jpg

Figure 10: http://images.library.wisc.edu.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/ArtHistory/S/136/t/262995t.jpg

Figure 11: http://images.library.wisc.edu.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/ArtHistory/S/63/r/245610r.jpg

- 1. Paul E. Sprague and Diane Filipowicz, “The Pew House,” in Frank Lloyd Wright and Madison: Eight Decades of Artistic and Social Interaction, ed. Paul E. Sprague (Madison, WI: Elvehjem Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1990), 109–110. ↵

- 1. “Pew House Exemplifies Wright’s Principles,” Wisconsin State Journal, February 19, 1995. ↵

- 1. Peter A. Rött, “Sustaining Wright 101,” Save Wright 2 (Fall 2011): 9. ↵

- 1. Peter A. Rött, “Sustaining Wright 101,” Save Wright 2 (Fall 2011): 9. ↵

- 1. “Pew House Exemplifies Wright’s Principles,” Wisconsin State Journal, February 19, 1995. ↵

- 1. Peter A. Rött, “Sustaining Wright 101,” Save Wright 2 (Fall 2011): 9. ↵

- 1. John Sergeant, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian Houses: Designs for Moderate Cost One-Family Homes (New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1976), 68. ↵

- 1. Paul E. Sprague and Diane Filipowicz, “The Pew House,” in Frank Lloyd Wright and Madison: Eight Decades of Artistic and Social Interaction, ed. Paul E. Sprague (Madison, WI: Elvehjem Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1990), 110. ↵

- 1. Donald G. Kalec, “The Jacobs House I,” in Frank Lloyd Wright and Madison: Eight Decades of Artistic and Social Interaction, ed. Paul E. Sprague (Madison, WI: Elvehjem Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1990), 91. ↵

- 1. John Sergeant, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian Houses: Designs for Moderate Cost One-Family Homes (New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1976), 68. ↵

- 1. Henry-Russell Hitchcock, In the Nature of Materials (New York: Duell, Sloan, and Pearce, 1942), 97. ↵

- 1. Frank Lloyd Wright, “In the Cause of Architecture” (Art Humanities Primary Source Reading 51, 1908), 1. ↵

- 1. Theresa Grupico, “Frank Lloyd Wright and Our Attitude Toward Nature,” The Forum on Public Policy, 2011, 9. ↵

- 1. Peter A. Rött, “Sustaining Wright 101,” Save Wright 2 (Fall 2011): 9. ↵

- 1. Frank Lloyd Wright, The Natural House (New York: Horizon Press, 1954), 134. ↵

- 1. “Pew House File #0910” (Isthmus Architecture Inc., n.d.), accessed April 29, 2016. ↵

- 1. Paul E. Sprague and Diane Filipowicz, “The Pew House,” in Frank Lloyd Wright and Madison: Eight Decades of Artistic and Social Interaction, ed. Paul E. Sprague (Madison, WI: Elvehjem Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1990), 113. ↵

- 1. Frank Lloyd Wright, The Natural House (New York: Horizon Press, 1954), 133. ↵

- 1. “Pew House File #0910” (Isthmus Architecture Inc., n.d.), accessed April 29, 2016. ↵