Chapter 1: Wright’s Life and Career

Prairie Period (1900-1910) (Alex and Katie)

Alexandra Pollach and Yusi Liu

The Prairie School was a movement made up of an intimate group of American architects who aimed at creating an architectural genre characteristic to and defining of the Midwestern United States. Architectural historian H. Allen Brooks was the first to coin the term “The Prairie School, the architects themselves never actually associated with this title. Brooks describes in his Frank Lloyd Wright and the Prairie School that the Prairie school movement is defined by architecture’s interconnectedness to the surrounding landscape, the open and the unique flow of the interior space, and the engagement and appreciation with the Arts and Crafts movement[1], while distinctly moving away from previous architectural inclusions, specifically European. The Arts and Crafts movement and the Prairie School both strived for simplicity and handcrafted ingenuity; these motives were “a response in opposition to the new assembly line, which they felt resulted in mediocre products and dehumanized workers.”[2]

Architect Frank Lloyd Wright is arguably, and infamously, the most notable of the Prairie School architects. The motives behind his architecture were driven by the intention to create of a solely American architectural identity. In the design, layout, and décor of his spaces, Wright rejected “historic and revivalist”[3] influences that would have been easily recognizable and attributed to previous European styles of architecture. In regards to his alignment with the Arts and Crafts movement, Brooks writes that Wright utilized the machine to enhance the natural heritage, and “used it to shape, but not to dominate, their aesthetic.” This relationship with Arts and Crafts allowed Wright to build genuinely site specific structures. The recognition of Wright for the specific sites is what ultimately created an architectural style that was uniquely American.

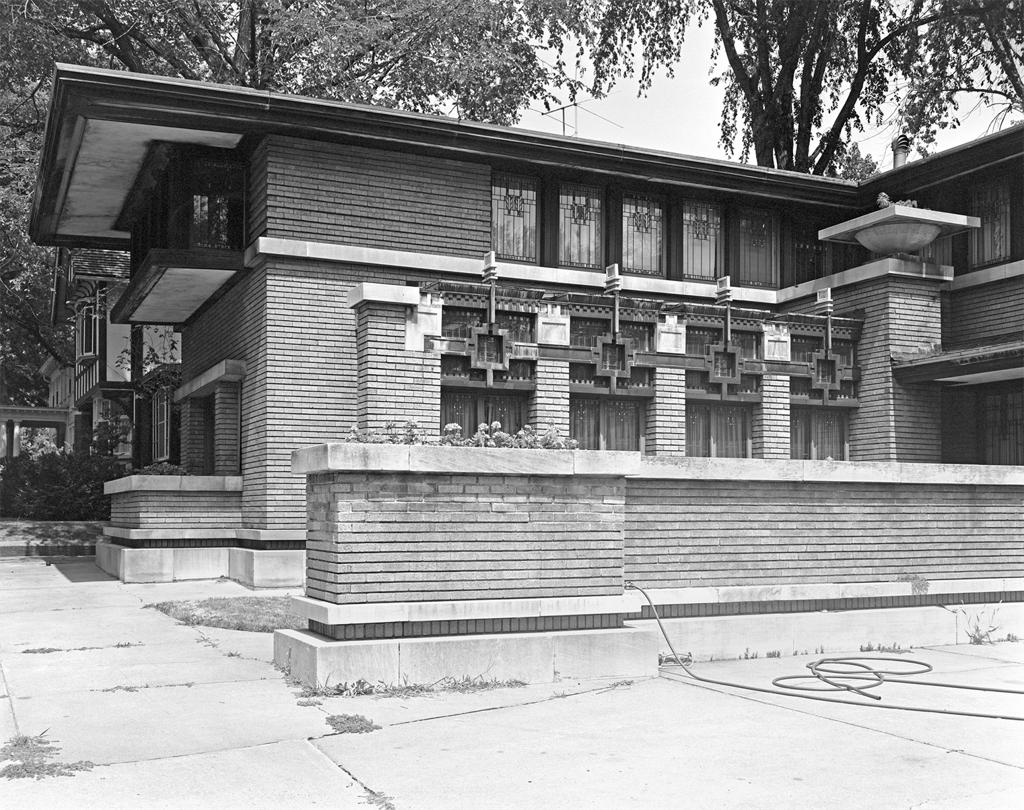

The sites of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie Style homes were each unique in choosing, catered to the surrounding angles and layout of the surrounding environment. However, these homes often didn’t find themselves in any extraordinary landscape. Characteristic of the Midwestern U.S. landscape, the sites resided on flat plots of land. Larkin writes in The Prairie Years: Master Works, “Wright’s prairie houses, for the most part, did not enjoy dramatic sites. They were built in sedate, suburban regions.”[4] Wright used horizontal and low angular lines to enhance the horizontality of the land itself. Frank Lloyd Wright set out to create a style of architecture never before established, and as Larkin beautifully puts, he took to the prairie as his thesis.[5]

Frank Lloyd Wright saw an integral relationship with the ground that he built upon tied to the houses that were on them. Most of these houses were single story, free of a basement and upper levels. Previous homes often included a basement, but Wright diverged from this practice. In a conversation regarding the basement, Wright stated, “I had an idea that every house in that low region should begin on the ground, not in it as they then began, with damp cellars”.[6] Eliminating the basement encouraged a unity between the base of the house to the specific site and dweller of the home alike.

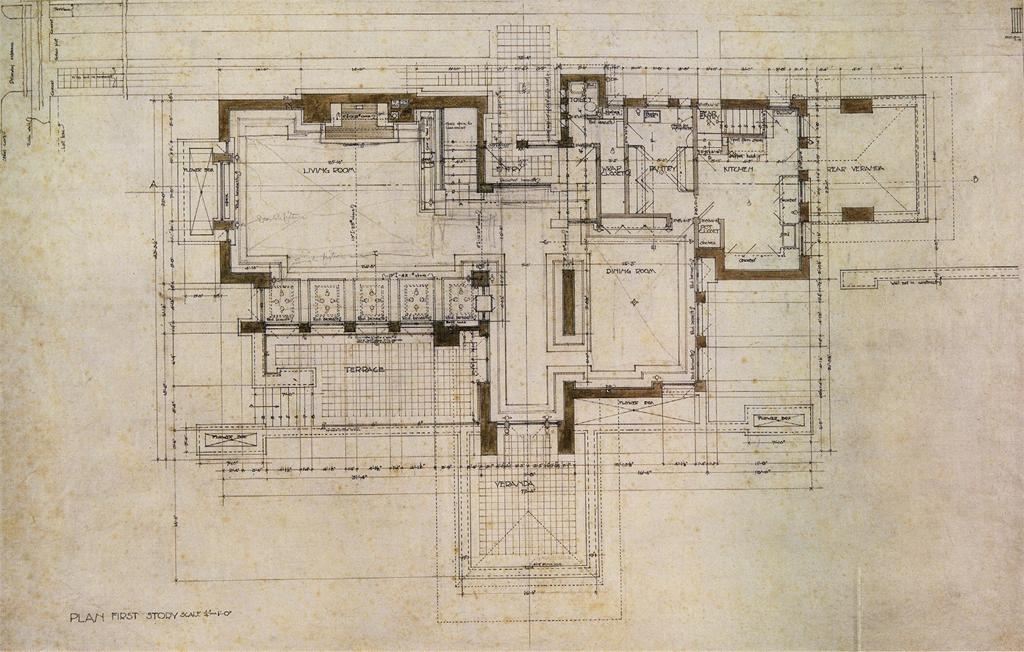

A notable example of a Prairie Style home by Wright is the Meyer May House (1908), in Grand Rapids, Michigan. This is a restored example, commemorated as a space restored exactly as Wright had originally intended. The flow of the Meyer May House, consistent with Prairie Style architecture, contradicted many previous practices in architecture. One example of this was the disregard of a symmetrical and axial flow of the home. The main entrance to the home was not on any major axis; instead it was intimately tucked away from the busy, bustling drag of the surrounding streets, providing privacy to the dwellers. Western architecture was generally defined by houses with large facades, porches, entryways, and doorways facing directly onto the main street. In contrast, and characteristic of Wright’s Prairie houses, entryways were tucked away from the public arena.

This creation of security and intimacy was common across East Asian Architecture, specifically Japanese homes. As Wright utilized cues from the plots of land, he also took to classic Japanese architectural styles for some ideas. Wright noted he never set out to imitate Japanese architectural style. Rather, In creating his own style, he honored and utilized the feelings of sanctity and organization created by Japanese architecture. **will need footnote here

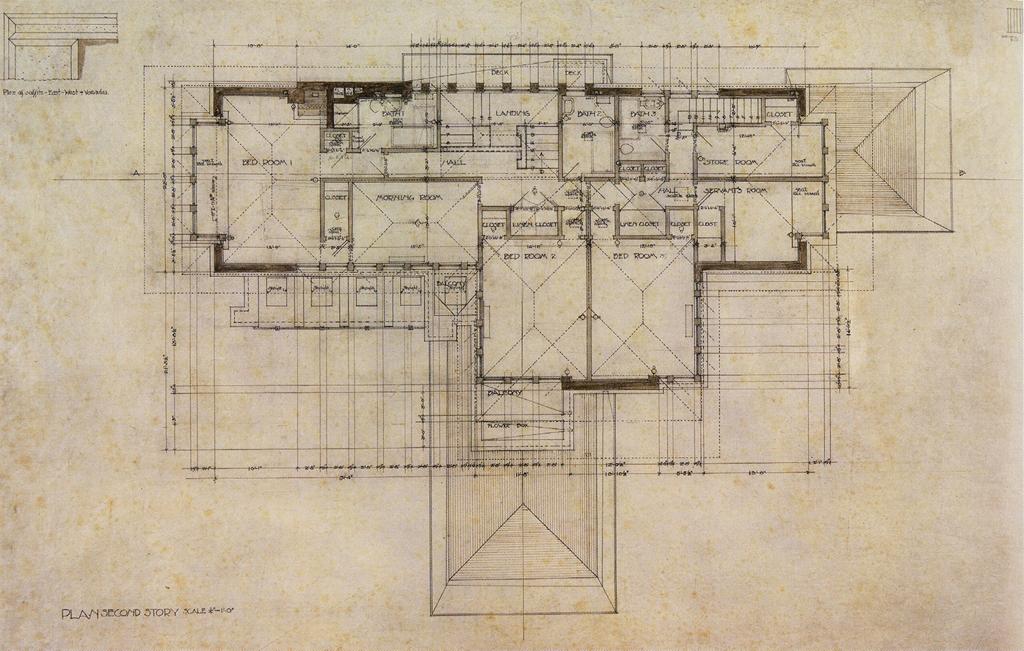

In regards to standard Japanese practice, Larkin writes, “The first and supreme principle of Japanese aesthetics consists in stringent simplification by elimination of the insignificant and a consequent emphasis of reality.”[7] Frank Lloyd Wright honored this principle. It dictated not only the space itself but the arrangement of it through the omission of excessive décor and furnishings. The furnishings of Prairie Style architecture were uniquely site specific. They aligned with the principle of honoring the surrounding environment, both interior and exterior; Wright was incredibly careful that furnishings would not take away from the simplicity of the space or reputation of the Midwestern prairie.

Many of Wright’s clients often insisted on moving into the newly built homes with their old furniture, particularly furniture that catered to the Victorian style architecture that the pieces previously inhabited. So to prevent the clients from doing so, Wright took to designing and installing pieces that were inseparable from the home. Book shelves, seating, cabinetry were all built directly into the walls to prevent the infiltration of furnishings that did nothing but clutter and interrupt his spaces. These pieces were often undecorated and unpainted, a stark difference from the client’s own pieces. This practice “produced the desired result of an interior uncluttered by unrelated objects, quieter and more harmonious”[8], aligning with the motifs and central foundation to Japanese lifestyles.

- Brooks, H. Allen. Frank Lloyd Wright and the Prairie School (New York: Braziller: Published in association with the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Design, 1984), 9-10. ↵

- "Prairie School Architecture, About." Prairie School Architecture. Digital Tiki, n.d. Web. <http://www.prairieschoolarchitecture.com/>. ↵

- "Prairie School Architecture, About." Prairie School Architecture. Digital Tiki, n.d. Web. <http://www.prairieschoolarchitecture.com/>. ↵

- Larkin, David, and Bruce Brooks. Pfeiffer. Frank Lloyd Wright: The Masterworks (New York: Rizzoli in Association with the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, 1993), 36. ↵

- Larkin, David, and Bruce Brooks. Pfeiffer, 36. ↵

- Larkin, David, and Bruce Brooks. Pfeiffer, 36. ↵

- Larkin, David, and Bruce Brooks. Pfeiffer, 97. ↵

- Larkin, David, and Bruce Brooks. Pfeiffer, 88. ↵