Chapter 1: Wright’s Life and Career

Religious Architecture

LauraLee Brott; Brianna Moritz; and Erin Green

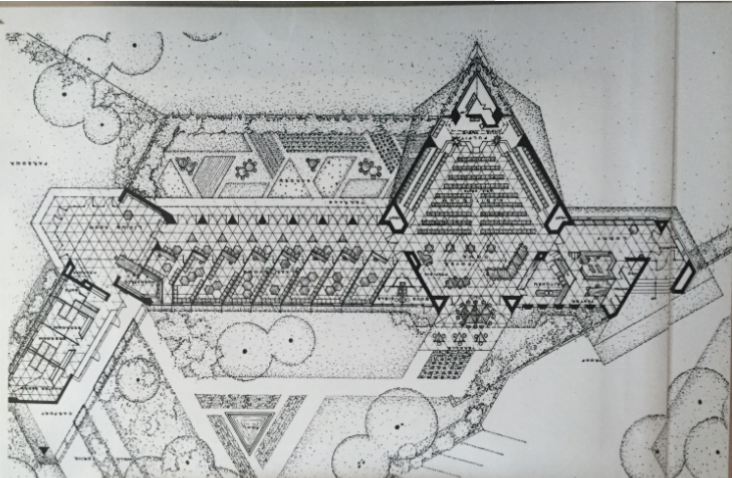

Frank Lloyd Wright built many spiritual structures throughout his career, which span a number of Christian denominations and religious communities. There is a trend in scholarship that focuses on how Wright’s domestic designs, namely Oak Park and buildings constructed during his Usonian period, infiltrate his religious structures – particularly with the inclusion of multifunctional spaces.[1] Yet there is also a lot that is gained by focusing on the religious structures themselves. This chapter will focus on three churches built by Wright: The Unity Temple built between 1905 and 1908; The Unitarian Meeting House completed in 1951; and the Beth Shalom Synagogue (Figure 3), constructed at the very end of his career, between 1954-1959. An investigation of Wright’s legacy within spiritual spaces, which can arguably be seen Thorncrown Chapel in Eureka Springs, Arkansas built around 1981, will be the last focus of this chapter.

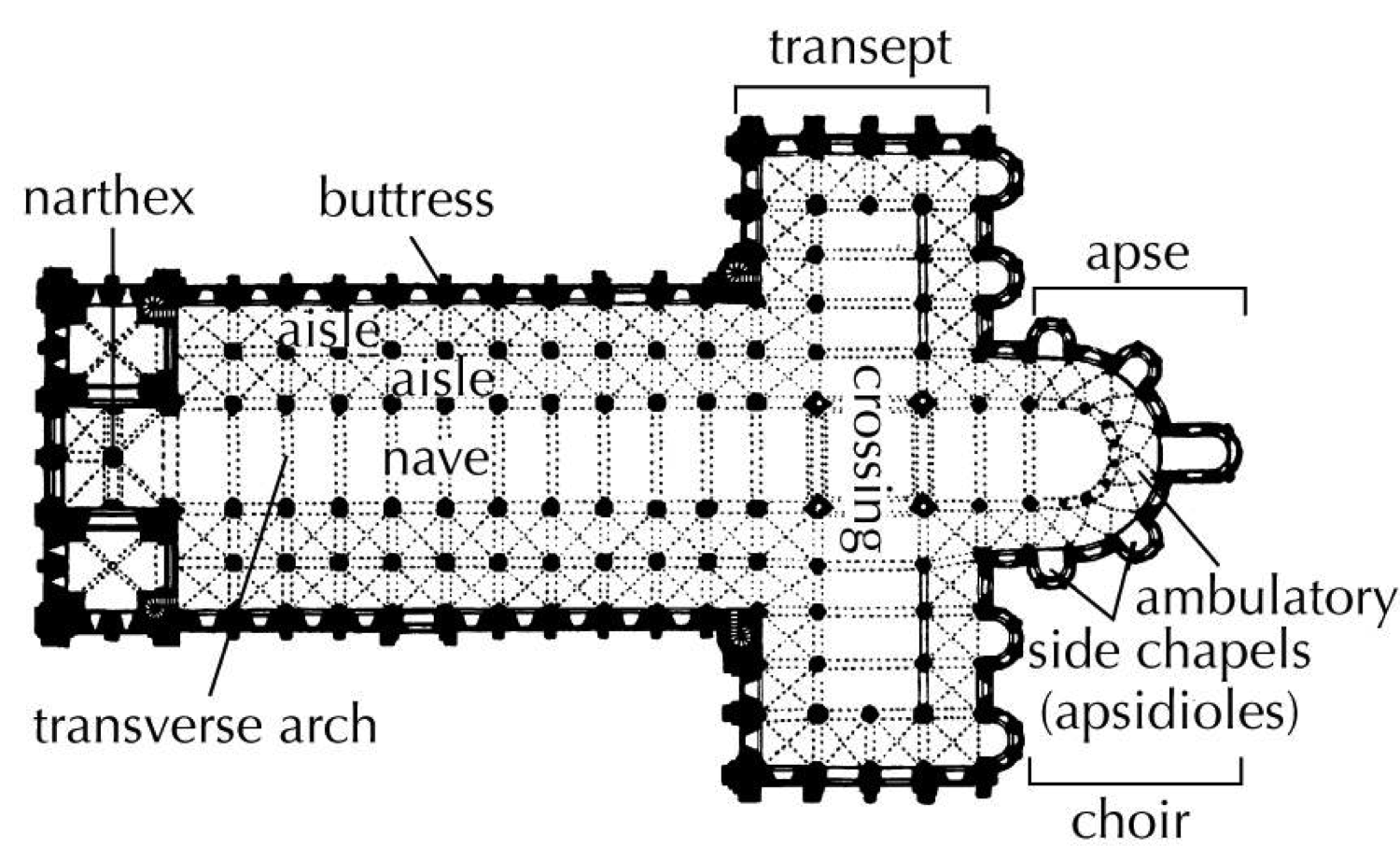

Looking at the exterior all three of these structures, it is immediately apparent that Wright’s designs do not contain the elements of traditional medieval church design. His churches do not include the iconic church steeple, nor do they follow a typical western Christian medieval basilica plan which mimics the shape of a cross (left image). The typical christian churches orients the altar space, or the “apse”, eastward – toward the sunrise and the fabled location of Paradise. Additionally, medieval churches are frequently set on top of a hill, serving as a statement of ideology. Wright did not follow any of these precedents, he sought to reformulate the shape of spiritual spaces. To Wright, sacred space was dictated by nature.

Amongst Wright’s first religious commissions is the Unity Temple was constructed for the Unitarian congregation in the suburban region of Oak Park, Chicago, during Wright’s earlier career. Commissioned in 1905, the structure is built on monolithic reinforced concrete. The Temple is bipartite; the lower building, termed the Unity House, was designed to serve social and educational functions, while the upper half served as the “chapel” space.[2] The “boxy” exterior stands in stark contrast to the western medieval type (left image); Wright was instead looking to early Christian and Byzantine forms (hence the name “Temple) for inspiration on the performative aspects of spiritual space.[3]

Amongst Wright’s first religious commissions is the Unity Temple was constructed for the Unitarian congregation in the suburban region of Oak Park, Chicago, during Wright’s earlier career. Commissioned in 1905, the structure is built on monolithic reinforced concrete. The Temple is bipartite; the lower building, termed the Unity House, was designed to serve social and educational functions, while the upper half served as the “chapel” space.[2] The “boxy” exterior stands in stark contrast to the western medieval type (left image); Wright was instead looking to early Christian and Byzantine forms (hence the name “Temple) for inspiration on the performative aspects of spiritual space.[3]

Like Byzantine churches, which emphasize the ritu alistic movement of icons through sacred space, Wright created a labyrinthine structure for Unitarian worship (right image). The congregation enters through a different doorway through which they exit, creating a continuous loop of movement through the space. The choreography of this “dance” was accentuated with expertly placed windows, which allowed light to flood in certain chambers throughout the day.[4]

alistic movement of icons through sacred space, Wright created a labyrinthine structure for Unitarian worship (right image). The congregation enters through a different doorway through which they exit, creating a continuous loop of movement through the space. The choreography of this “dance” was accentuated with expertly placed windows, which allowed light to flood in certain chambers throughout the day.[4]

About fifty years later, Wright was asked to design a space for the Unitarians in Madison, Wisconsin. The Unitarian Meeting House was completed in 1951. Purposely located outside of the city center, Wright worked with the natural landscape to connect exterior to interior; large spans of glass windows allow for the illusion of the outside projecting in. The altar space is oriented northward; a “prow” shape injects itself into the hill that the church sits on, and commands the attention of the viewer from both inside, and outside of the space. The Unitarian Meeting House in particular will be the focus of Chapter 7.[5]

About fifty years later, Wright was asked to design a space for the Unitarians in Madison, Wisconsin. The Unitarian Meeting House was completed in 1951. Purposely located outside of the city center, Wright worked with the natural landscape to connect exterior to interior; large spans of glass windows allow for the illusion of the outside projecting in. The altar space is oriented northward; a “prow” shape injects itself into the hill that the church sits on, and commands the attention of the viewer from both inside, and outside of the space. The Unitarian Meeting House in particular will be the focus of Chapter 7.[5]

Just before Wright’s death, in the early 1950s, he designed the Beth Sholom Synagogue in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania. In a letter to the Rabbi in 1954, Wright explained his plan to create “…a temple that is truly a religious tribute to the living God.” The finished product is composed of three concrete masses, which act as the foundation for a metal “tripod” that extends upward, forming the building’s skeleton. The rest of the exterior is entirely composed of glass panes, which allow for varying interior light effects throughout the hours of the day. At night, the building seems to glow; a beacon of light in the darkness. Inside the main auditorium, a large and open space, stamped metal motifs resembling the Jewish menorah adorn the large metal supports; all chairs face a raised area where the Torah is read. Wright was praised by the current rabbi for his attention to detail, who described the synagogue in a letter to Wright as “…a design of beauty and reverence. In a word, your building is Mt. Sinai.”[6]

Wright’s influential design of religious spaces continued long after his death, particularly through his members of the Taliesin fellowship. In 1980, for example, one of the most outstanding Wrightian chapels, called Thorncrown, was built in Eureka Springs, Arkansas, by local architect E. Fay Jones. Jones was one of the last apprentices at Taliesin for almost a decade during Wright’s final years. His designs carried on many of Wright’s principles, including the use of native materials, simplicity of design, and integration of the building to its site. Thorncrown was no exception to these principles in combining the ‘cathedral-esque’ traditional with a lightweight, postmodern piece of art, however, Jones kept to some of his own principles in favor of verticality as opposed to Wright’s usual horizontality. This “Ozark Gothic” won Jones the AIA Gold Medal in 1990, which helped put Eureka Springs on the map for its beautiful mountainside views. Of course, E. Fay Jones is just one of the dozens of apprentices with an adapted Wrightian style, but as a successful architect independent of Taliesin’s fellowship, Jones shows how his time with Mr. Wright proved extremely rewarding throughout his entire career.

Bibliography

Alofsin, Anthony. Frank Lloyd Wright The Lost Years, 1910-1922. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press, 1993.

Compton, Ellen. “Fay Jones (1921–2004) – Encyclopedia of Arkansas.” Fay Jones (1921–2004) – Encyclopedia of Arkansas. The Central Arkansas Library System, 25 Feb. 2015. Web. 05 Apr. 2016. <http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=447>.

“Family History.” Accessed March 28, 2016. <http://www.unitychapel.org/familyhistory/>.

Hamilton, Mary Jane. “The Unitarian Meeting House.” In Frank Lloyd Wright and Madison: Eight Decades of Artistic and Social Interaction, edited by Paul E. Sprague, 179-188. Madison, WI: The Elvehjem Museum of Art, 1992.

Larkin, David, and Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer. Frank Lloyd Wright: the Masterworks. New York: Rizzoli, 1993.

Levine, Neil. The architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright. Princeton Unviersity Press, 1996.

“Thorncrown Chapel Architecture.” Thorncrown Chapel Architecture. Thorncrown Chapel, Inc., 2015. Web. 05 Apr. 2016. <http://www.thorncrown.com/architecture.html>.

- Wright’s affinity for multi-use spaces can perhaps be traced back to his first religious project. During the summers in late 1870s and early 1880s, Wright helped to design a Unitarian chapel for his family's’ property in Hillside, Wisconsin, under Chicago architect Joseph Lyman Silsbee. Named the Unity Chapel, the space was not only used for worship; meetings, social gatherings and occasional school lessons were also held there. The chapel is simple in layout and decoration, composed mostly of a rectangular space with a small wooden podium for preaching. See Neil Levine, The architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, (Princeton Unviersity Press, 1996), 80-81. ↵

- Levine, The architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, 40. ↵

- Levine, The architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, 41. ↵

- Levine, The architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, 44. ↵

- David Larkin and Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, Frank Lloyd Wright: the Masterworks, New York: Rizzoli, 1993, 227-228. ↵

- Larkin, David, and Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer. Frank Lloyd Wright: The Masterworks. New York: Rizzoli, 1993.264. ↵