The Eugene Gilmore House (aka Airplane House) (1908-9)

The Eugene Gilmore House (1908-9)

Yusi Liu and Alexandra Pollach

In construction of the Gilmore House, Frank Lloyd Wright abandoned use of previous architectural revival styles common to the houses in the surrounding Madison area as well as other parts of the U.S. Instead, Wright used dramatic angles, lot orientation, and décor to establish himself as a Prairie Style architect, the Gilmore house being a dynamic representation of the goals of the Prairie Style.

The Eugene A. Gilmore House, commonly known as the “Airplane” House, is a significant example of Wright’s Prairie period in Madison. The area of University Heights where the Gilmore house resides was first developed in 1892. Demand for single-family housing away from the university campus was growing in the late 1890s as the downtown residential area was growing more and more crowded. The plot of land, 106 acres, was sold in 1893 by a private owner to a local development business, the University Heights Company.

Little residential development occurred in University Heights until the turn of the twentieth century. The only notable home built up until that point had been “another large, late Queen Anne-style home built in 1898”.[1] Part of the reason growth was so slow was up until the 1900s was the area did not have reliable city gas, water, or electricity. After 1900, when these residential necessities became accessible in University Heights, real estate prices for the partitioned lots skyrocketed. On June 3rd of 1904, possibly the most predominant and well known sale was made by two university professors, Eugene A. Gilmore and Michael Vincent O’Shea. Block 16 sat upon the highest brow of the elevated University Heights, a plot of land ideal for what would become one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s most famous Prairie Style homes.

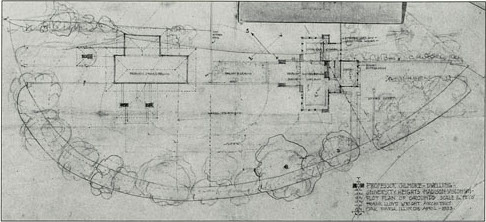

The original plan for the home, titled “Professor Gilmore-Dwelling” from April of 1908 is almost identical to the built structure, only rotated 90 degrees from its final orientation (fig. 2). The Gilmore family approached Wright in the prime of his Prairie Style period. At this point, he had built, and mastered, a number of previous homes of a similar style so Wright was confident in the opportunity that awaited the Gilmore plot of land. Richard T. Ely, another university professor overseeing the project noted, “Last night I looked at his [Gilmore’s] new plans and liked them very much. He is going to have an attractive house and his place will be one of the showplaces in the city I am sure.”[2]

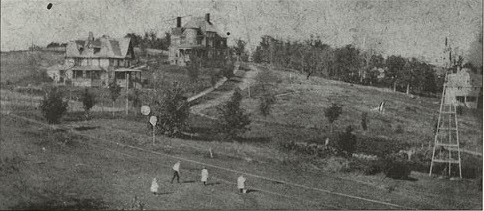

The house stands on highest point of the University Heights subdivision, presenting a wide-angle view of Madison (fig. 3). When the original planning for University Heights was being done, space was divvied up into individual lots and streets were arranged through an “organic and curvilinear plan as one approached the summit.”[3] The street formation encourages a drawn out journey to the highest elevated land, this land at the crown of the hill and was granted with the most esteemed and largest lots (fig. 4).

The materials used for the exterior of the Gilmore House are predominantly wood and stucco.[4] Wood trim bands gird the skin-colored stucco all around the house in a number of intersecting corners across different levels of the home. The batten-seam roof is made of copper, a material favored by Wright.[5] The roof slopes at an extremely low angle; for a visitor standing at the base of the home, a view of the top of the roof is not permitted which, despite how giant the house actually is, creates a very low and embedded sense consistent with the surrounding geography. Wright also takes consideration in the situation of the windows on the Gilmore home. Windows placement appears natural and organized, no window conveys a sporadic nature or appears out of place. The windows are the only clue on the exterior of the home into how many stories the house could actually be; the intersecting angles, walls, and roof make it hard for someone on the exterior of the home to discern how many levels there really are. The windows on the home are consistently positioned directly above another on the various stories; Wright connects an extensive band of windows across an entire wall of the home, further emphasizing his interest in horizontality. The shape and decoration on each window is consistent with the next. The decor on the windows are characteristic of Wright’s geometric style, decorated with leaded glass forming patterns of squares and linear lines.

The main entrance to the Gilmore house is tucked far back from the sidewalk and not obviously visible from the street (fig. 5). Two sets of staircases, one branching from the road to an elevated sidewalk, then another from the sidewalk to the actual plot of land (fig. 6). From here, an extended walkway leads to the front door. This walkway is sectored by a patch of greenery in the middle. The front door is turned ninety degrees from the direction of the walkway, creating a sense of seclusion from the residential street. It is intimately tucked and embedded deep into the home, covered by flooring above (which is actually another entryway). It almost feels like a cave. The entryway is covered by vegetation, furthering the sense of a cave. Furthermore, the Airplane house has no secure enclosure. The house is openly situated on a large plot of land without any fence or ornament around the exterior of the plot.

A dynamic feature in the Gilmore house is the diagonally oriented, triangular porch at the northeastern end. The porch is on the second floor and has a sharp ninety degree turn in relation to the orientation of the rest of the house (fig. 7). The triangular porch projects outward from the house, in contrast to the rectangular porch on the first story. The composition of the house, the T-shape with the copper roof and extending wings on either side, brought the nickname “Airplane House” in the neighborhood.

Prairie Style architecture aimed at creating houses that shared a relationship with the respective landscape where the house was located. Horizontal lines were the most common inclusion of this architectural style, highlighting the lowness and flatness of the surrounding Midwestern landscape. However, the landscape of the Gilmore house is not flat, and certainly is not low (recall it is the highest point of land in the University Heights area, situated on the tip of the crown of the land). So how then does Wright take to this specific land for inspiration? The magnificence in size of the Gilmore house is made possible because of the steepness and grandness of the land itself. The house is built in such a unique way that visually it continues the shape of the hill, so naturally constructed that it appears a part of the geography. To provide a contrast, had the same Gilmore house been built on a flat, low plot of land, this house arguably could not be considered Prairie Style because of how site specific the house is. On a flat plot of land, the house would be dominate, not complement the landscape, and ultimately do a disservice to the land it resides upon.

As mentioned, the Victorian style Buell House sits directly across the street from the Gilmore House (fig. 8). It was constructed prior to completion of the Gilmore house. In simply looking at the two houses, it is very clear how far Wright moved away from Victorian ornamentation and structural inclusions. Every decision Wright makes at the Gilmore house is notably in complete opposition to the decisions of the Victorian home. The Victorian Style Home across the street lacks unity and harmony with the land. It stands very tall and poses a dominating relationship against the land it is built upon, in contrast to the Gilmore home’s evident relationship with the landscape.

In further contrast, it has an obvious and straightforward main entrance, only a few feet from the residential sidewalk. The entryway is oriented the same direction as the rest of the house, creating a very “in your face” sense when standing in front of the house. It offers no privacy for the resident as the entryway is unrestricted from the street. The roof of the Victorian house is perhaps the most striking contrast between the two houses. Standing at the base of the house, one can clearly still see the tip of the roof due to its steep slope and domineering height. The height of the roof is almost taller than any single level of the home. Whereas the roof on the Gilmore home is a careful cap continuing the geography of the plot of land, the roof on the Victorian home is an element in its own right, furthering its sense of domination against the land. The materials of ornamentation are not natural and create an even further sense of dissonance between the space and surrounding landscape. The windows are sporadically placed and there is no consistent window shape as there is in the Gilmore home. In contrast to Wright’s Gilmore House windows, these windows pose no clear organization in spacing or location on the house. This sporadic organization of window furthers a discord between the land and house. Unlike the Gilmore House, there is no sense of harmony created with the rest of the home nor landscape alike.

Prairie Style homes, due to the associated definition of lowness/horizontality, are often overlooked and underestimated for their splendor in size. An exceptional comparison between the homes is how notably grand they both really are. Both of these houses are enormous; however, the execution of this enormousness by Wright is done in a much more organic and mindful way at the Gilmore house. Wright was consistently in touch with the sanctity of nature. He would have considered the Victorian home a disservice to the land and this disservice is exactly what Wright was aiming against.

- Timothy Heggland, “The Gilmore House,” in Frank Lloyd Wright and Madison: Eight Decades of Artistic and Social Interaction, ed. Paul, E. Sprague (Madison, Wisconsin: Elvehjem Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1990), 45. ↵

- Heggland, 47. ↵

- Heggland, 45. ↵

- "Airplane House" National Register nomination ↵

- "Airplane House" National Register nomination ↵