The Herb and Katherine Jacobs House (1936)

The Herb and Katherine Jacobs House (1936)

Christopher J. Slaby; Claire McDonald; and Garen Alexander

Introduction.

The Herb and Katherine Jacobs House was built for Herb and Katherine Jacobs in 1936, and it is located at 441 Toepfer Avenue, Madison, Wisconsin. Otherwise known as Usonia I, the house was built to accommodate a simple living style for the American masses, and was part of the Usonian movement that occurred after the Great Depression. Wright accepted the challenge of building a low-cost, post-depression house after Harold Wescott, Katherine’s cousin and a student of Wright’s for a summer at Taliesin, made the suggestion to the couple.[1] This was the first commission of Wright’s where the budget was the most important factor. However, Wright greatly exceeded the Jacobs’ original budget of $5,000, which was typical behavior of the ‘rich man’s architect.’[2]

Herb’s new job at the Capital Times with a $35 per week income in Madison meant moving from Milwaukee, where Herb had been reporting for The Milwaukee Journal, so Herb and Katherine first and foremost desired a low-cost house where they could raise their daughter, Susan. Wright and the Jacobs couple had a smooth working relationship, on the contrary to Wright’s reputation to be stubborn and insistent in collaborations with clients and builders.The Jacobs liked most of Wright’s ideas and were never concerned about the steadily increasing cost of the house. Having both been raised in families with little money, Herb and Katherine made no sacrifices when it came to living simply in their Usonian home. Over the five years that the Jacobs occupied the home, they most appreciated being constantly surrounded by the beauty of Wright’s design.[3]The house’s current owner, Jim Dennis, bought the home for this very reason in 1982, despite the fact that the purchase put him into debt.[4] The extensive renovations required for the house at the time did not detract Dennis from the possibility of owning one of Wright’s first Usonian homes.

Description.

The Jacobs House was built of almost entirely natural materials, mostly redwood, brick, glass, and concrete. The exterior redwood finish contrasts beautifully against both snow and greenery. It is a moderately small house, boasting 1552 square feet with two bedrooms and one bathroom[5]. Unlike many Midwestern homes, the Jacobs House does not have a fully functioning basement, and this structural component is shared between all Usonian homes. The low slung, horizontal design of the structure gives the Jacobs House a very sleek shape. The structure of the house itself is designed in an Ell-shape that wraps around the backyard garden area. Floor to ceiling glass windows in the living room help to integrate both the interior and exterior spaces, as Wright always emphasized the importance of nature in relation to the home[6]. However, one cannot help but notice that the house lacks a garage, and instead has a carport. Wright felt that garages were not a necessity of a young American family, and therefore decided to coin the term “ carport” because it achieves the same goals as a garage. “A car is not a horse, and it doesn’t need a barn,” Wright proclaimed to Herb Jacobs.[7]

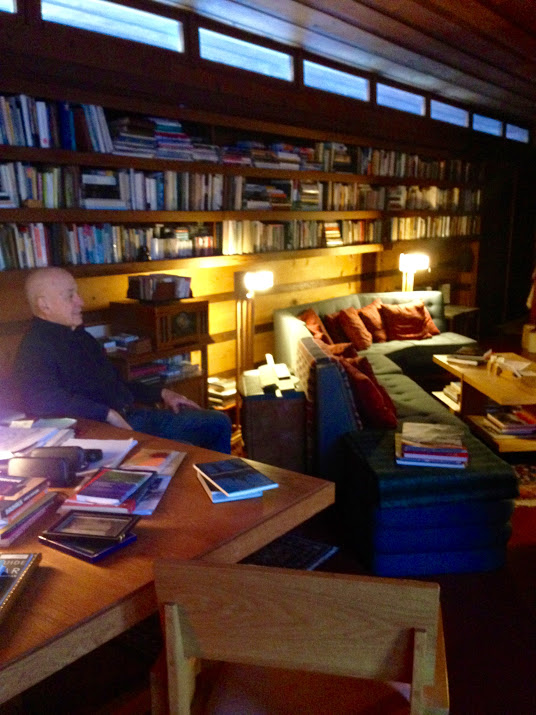

Photo by Claire MacDonald, April 2016

The narrow front entrance quickly expands into the largest living space in the entire house; this contraction and expansion technique was used frequently by Wright in his architecture. Another interesting similarity among Usonian homes’ living areas is that the Cherokee red concrete floor. This is largely considered a design flaw, as the radiant heating system sits below the concrete and cannot warm the floors as well because of the concrete absorbing the heat. The living room, like almost all of the rooms in the Jacobs House, flows right into the kitchen and dining area, as Katherine Jacobs wanted to be able to entertain guests during parties while she was cooking. The kitchen area is quite small, and this is also a relatively common feature of other Usonian houses, as no single space in the house would really be considered large as Wright stressed the importance of efficiency in his architecture[8]. He wanted the kitchen to be just large enough, but not too large or distracting from the other rooms of the home. Moving through the kitchen, a long hallway connects the kitchen and living areas with the one bathroom of the house, bedrooms and office. The rooms themselves sit on the Northeastern wing of the house which shields them from the sun, an important design aspect because the house has no air conditioning system.

From a design standpoint, the Jacobs House is truly a work of art. Its simplicity and utilization of space are truly unique to Usonian homes. The Jacobs’ modest backgrounds made for a smooth transition into the simple lifestyle the home required, being that Wright eliminated many unnecessary features to lower the cost and that this kind of simplicity was concordant with his Usonian vision. After the Jacobs moved to live on farmland, the house had several different owners who improperly cared for the house, leaving the current owner, Jim Dennis, with a beautiful yet decrepit structure that needed serious work.

Jim Dennis, Living with Frank Lloyd Wright

Herb and Katherine Jacobs actually moved out of their home in 1942 to live in a more rural area. The Jacobs House then had six different owners over the next forty years. When we spoke with Bill Martinelli, who helps Jim Dennis with the house, he noted that it was more than a fixer up.[9] The single largest issue was the roof. When holes would develop, owners added asphalt to seal them. This went on for decades, creating layers of asphalt and adding extra weight onto the joists. Another issue was the retaining wall for the carport. The second owner of the home wanted a garage, but Wright would not agree to that. The compromise was a brick wall on the North side, but this did not last well, causing the carport to sag badly. The wooden exterior of the house was finished with creosote, which needed to be extracted. Other issues included vents on the roof that were not connected to anything and soffits in worse condition than they appeared. Despite all of this—some of which he did not know about—Jim Dennis decided to buy the Jacobs House in 1982.

Though Jim Dennis has had a long and distinguished career as a scholar of American art at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, he first heard about Wright much earlier. In fact, Jim recalls that he first became familiar with the architect’s name around the age of eight, when he lived in northwest Ohio, where there were some Wright buildings. Jim also tells the story of an aunt who went to hear Wright give a talk. She and Jim’s uncle lived in a Neo-Colonial nineteenth-century farmhouse. At some point Wright spoke of his dislike for that type of architecture, which caused Jim’s aunt to stand up and say “We live in a colonial house and we love it.”

Later, Jim came to Wisconsin as a graduate student and became friends with a local who liked to take walks and look at architecture. At that time Jim knew that Wright had a strong connection to Madison and that Wright’s home and school, Taliesin, were nearby. In 1975, Jim went to a talk that Herb Jacobs gave at the Unitarian Meeting House. Finally, one day he was speaking with a student, Brad Lynch, and asked him if he had ever seen the Jacobs House. When Brad indicated that he had not, they went over to see it. When they arrived there was a “For Sale” sign in front. Jim says that buying the house was because of Wright. He described the architect as “an incredible artist.” He noted that despite its decrepit condition in 1982, it was beautiful.

When Jim bought the house, he knew that it would need some work. Renovations began right away, in late 1982. The major period of renovations lasted until the fall of 1985. Jim was in charge, but he also consulted with an architect friend, John Eifler, and the architectural student Brad Lynch. Jim also had help with the labor from his sons. Though the renovations were a challenging process, Jim said, “We all loved it.” He called it a “labor of love.” Because it was a custom-built house, John Eifler drew up new plans, working with the originals that Jim rented from Taliesin. In addition to the many issues noted above, Jim was surprised to find himself without heat in January of 1984. A piece in the experimental floor heating failed, thus shutting off the home’s entire heating system. They had to jackhammer the floor and replace the part. Despite the failure of the one part, Jim says that everything else about the heating was in great condition.

Wright indicated to Herb and Katherine that if they wanted to live in an affordable home of his, they needed to live a simple lifestyle. There is no garage, no basement, a small kitchen, and one small bathroom. When asked, however, Jim Dennis says that he did not really have to alter his life much, in order to match Wright’s imposition of simplicity. Jim says that he does think of the Jacobs House as his home. Yet living here is different from living in just about any other home. Because Wright had his own particular version of how a building should look and work, the Jacobs House can be a difficult place to live. Parts of it were falling apart when Jim bought it. Wright’s creativity, as in the floor heating system, was interesting, but an interesting idea does not make up for a cold home. Yet these quarks did not deter Jim’s passion and enthusiasm for the house. He added steel to support the carport. He has the exterior sanded and resurfaced as needed. And, as Joe added, you just learn to live with some things.

While much of Jim’s interventions were aimed at preserving the home and its history, he is not stuck in the past. He said that in order to bring back original aspects of the home he wanted to improve it. Such a suggestion might sound like heresy to some Wright fans, but it is Jim’s realistic and sincere way to keep the Jacobs House alive. Jim referred to the renovation as a “labor of love,” but the same moniker could just as easily apply to Jim’s tenure as owner and steward of the Jacobs House. The home is significant in many ways, but some of these do not seem to interest Jim. When asked about Wright’s larger Usonian plan, Jim responds with ease that it was a failure. The homes were not affordable, he points out. Likewise, when queried about Wright’s private life, which many find particularly entertaining, Jim said, “I stay out of it.” Jim’s dedication to the Jacobs House is grounded in the home itself, not in the lore or lure of Wright. It took a lot of time, effort, and money to renovate the house. It takes an equal amount to maintain it. But Jim goes even further, sharing his home with many others who come from all over the world. The Jacobs House is Jim’s home. At the same time, of course, it is a famous building, created by a famous architect. What stands out about the Jacobs House, however, after talking with Jim Dennis, is the way that this home has inspired one man to hold on to history and to share it. There certainly are other legacies to be found here, but the story of Jim Dennis’s time living so closely with Frank Lloyd Wright is now just as part of the Jacobs House as the building, Herb and Katherine, and Wright himself.

Bibliography

Alofsin, Anthony. Frank Lloyd WrightThe Lost Years, 1910-1922: A study of Influence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993.

Dennis, Jim, Bill Martinelli, and Joe. Interview by Garen Alexander and Claire MacDonald. April 28, 2016.

Kalec, Donald G. “The Jacobs House I.” In Frank Lloyd Wright and Madison: Eight Decades of Artistic and Social Interaction, edited by Paul E. Sprague, 91-100. Madison: Elvehjem Museum of Art/University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1992.

Jacobs, Herbert with Katherine Jacobs. Building with Frank Lloyd Wright: An Illustrated Memoir. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1978.

Larkin, David and Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, ed., Frank Lloyd Wright: The Masterworks (New York: Rizzoli, 1993).

Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks. The Essential Frank Lloyd Wright: Critical Writings on Architecture. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2008. Print.

Rosenbaum, Alvin. Usonia: frank Lloyd Wright’s Design for America. Washington , D.C.: Preservation Press, National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1993.

- Frank Lloyd Wright and Madison: Eight Decades of Artistic and Social Interaction. 94. ↵

- The Essential Frank Lloyd Wright: Critical Writings on Architecture. 347. ↵

- Frank Lloyd Wright and Madison: Eight Decades of Artistic and Social Interaction. 98. ↵

- Dennis, Jim, Bill Martinelli, and Joe. Interview by Garen Alexander and Claire MacDonald. ↵

- Frank Lloyd Wright: The Masterworks. ↵

- Frank Lloyd Wright: The Lost Years, 1910-1922: ↵

- Building with Frank Lloyd Wright: An Illustrated Memoir. 94. ↵

- Usonia: frank Lloyd Wright’s Design for America. ↵

- Much of the information in this section comes from an interview by the authors of Jim Dennis, Bill Martinelli, and a former student named Joe who worked on the renovations. The interview was conducted on Thursday, April 28, 2016 at the Jacobs House in Madison, Wisconsin. ↵