Chapter 2: The Robert Lamp House (1903)

The Robert Lamp House

Sela Gordon and Stephanie Klem

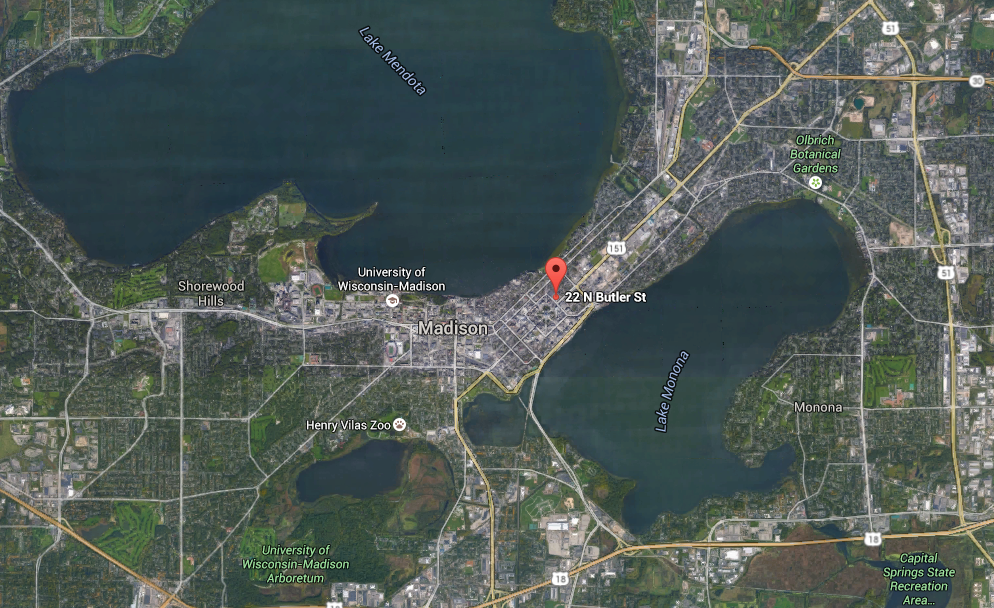

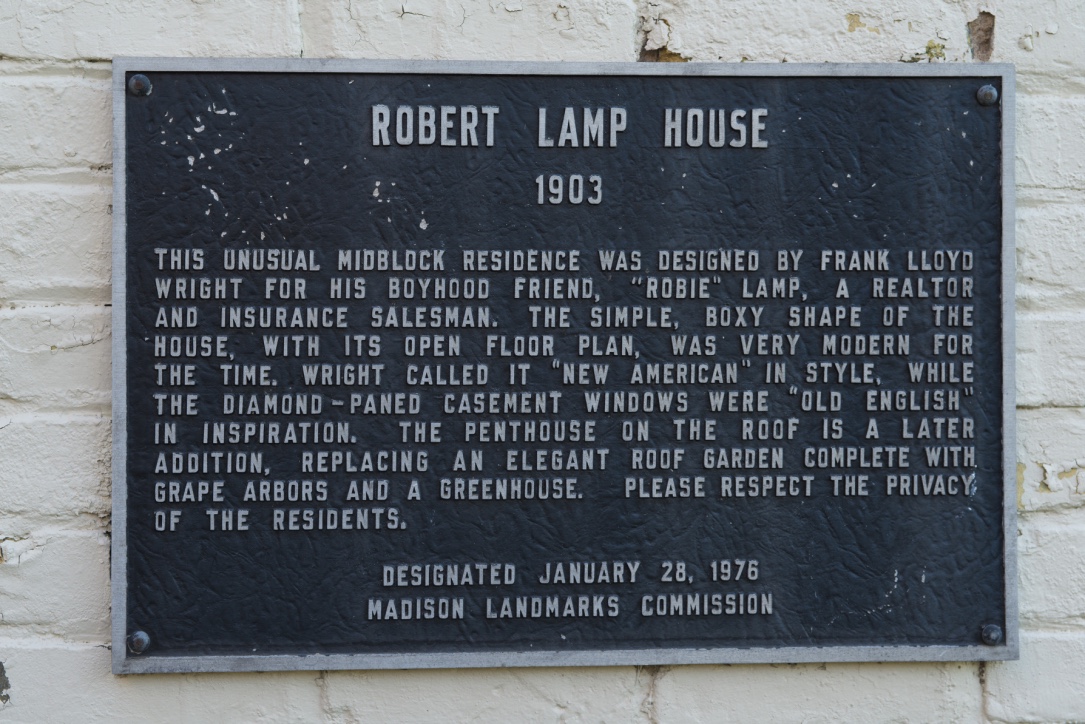

The Robert Lamp House was constructed in 1903. It is located at 22 North Butler Street, one and a half blocks from the Capitol Square in downtown Madison, Wisconsin, on a narrow isthmus between Lakes Monona and Mendota. The Lamp House is arguably Wright’s “most personal work”[1] in Madison in that its patron, Robert M. Lamp (1866-1916), was one of Wright’s closest childhood friends.[2] Wright described “Robie” Lamp as his “one intimate companion” and “heart-to-heart comrade.”[3] Lamp, who was disabled with atrophied legs, requested a compact dwelling that would afford him easy access to his downtown real estate office, a sense of suburban privacy, and, most importantly, breathtaking views of both lakes.[4]

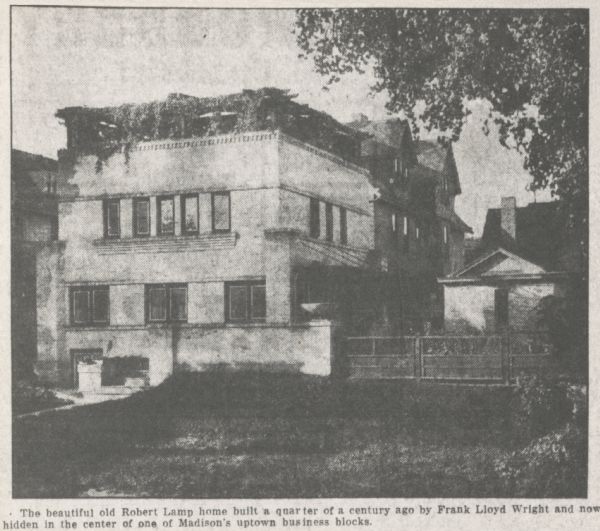

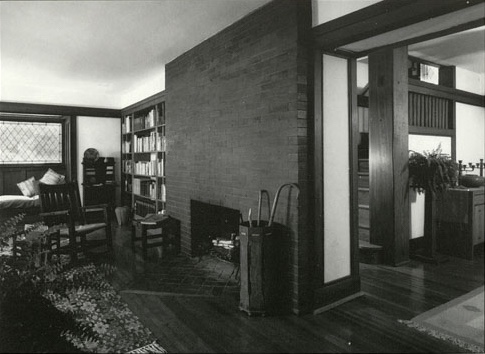

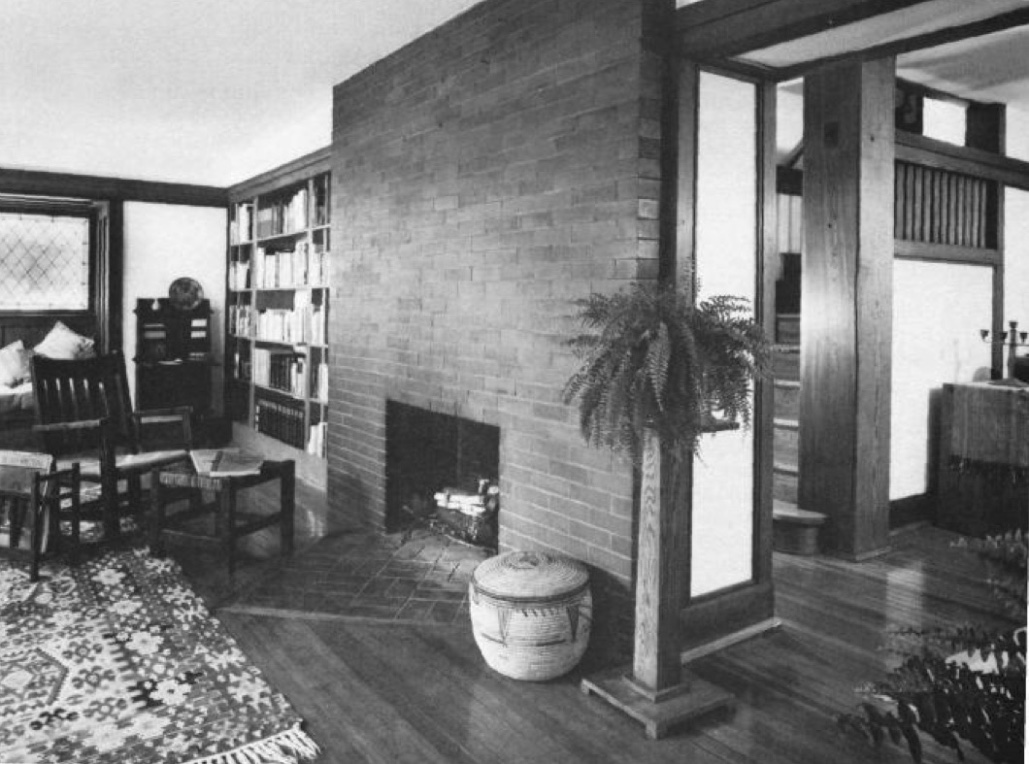

Above, left: Comic portrait of Robert Lamp for stepson Fay Shaw, ca. 1912-13. Holzhueter, “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp” (Winter 1988-1989), 125. Above, center: North façades including roof garden and pergola. Photograph in the Wisconsin State Journal, April 30, 1913, 5.75 x 5 inches, Wisconsin Historical Society. Above, right: Living room, dining room, staircase, balustrade, with interior furnishings. Photograph by Joseph Paskus, Chazen Museum of Art. Holzhueter, “Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp” (1990), 22.

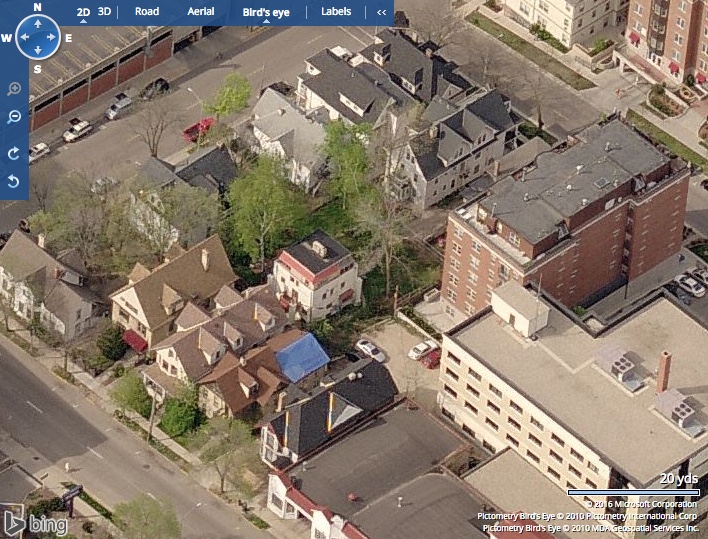

Wright obliged by situating the house in the center of a city block on one of the highest points of the isthmus, by adding fill to elevate its base, and by creating a roof garden.[5] In 1903, the Madison Democrat called the Lamp House a “new American type,”[6] and in 1907, Wright devised a floor plan based on the Lamp House for an article in the Ladies Home Journal.[7] Wright’s design for the Lamp House is one of his earliest experiments with abstraction and transitional in style, making it one of his most important structures predating World War I.[8] It is also his earliest surviving work in Madison.[9] The Lamp House was designated a city landmark in 1976, and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.[10] But despite its architectural significance, the Lamp House is Wright’s least known work in Madison.[11]

The Lamp House has gained in notoriety in recent years. Beginning in 2009, Madison citizens formed committees and voiced their concerns over a slew of real estate proposals that would fundamentally alter the historic Lamp House site. The City of Madison convened a Lamp House Ad Hoc Plan Committee, which produced a report in January 2014 with recommendations for maintaining the site’s character. Significant for its location in the center of a block, the Lamp House became the center of a local controversy over real estate development and historic preservation. The Lamp House constitutes an interesting case study for exploring these apparently competing issues.

Describing the Lamp House: Structure and Style

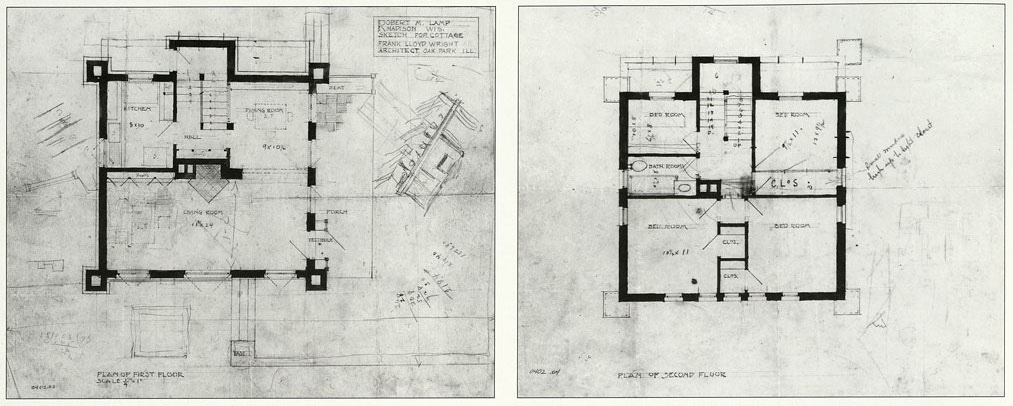

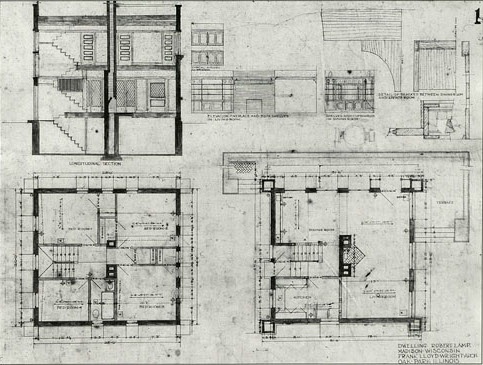

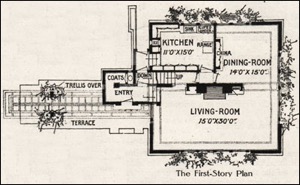

The Lamp House is a brick, three-story, single family home, with a modified cubical plan, terrace with parapet, enclosed side porch, rear airing porch, full basement, and flat roof. The plan is approximately 2,200 square feet, with a living room, dining room, and kitchen on the first floor; four bedrooms on the second floor; a den on the third floor (which Wright did not construct); and a total of three bathrooms.[12] Wright included a central hearth and a steam heat system rather than forced-air.[13] The house sits on a 0.16 acre or 6,996 square-foot lot.

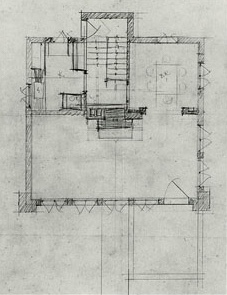

Above, left: Wright’s first-floor plan, scheme one. Above, right: Wright’s second-floor plan, scheme one. Holzhueter, “Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp” (1990), 19.

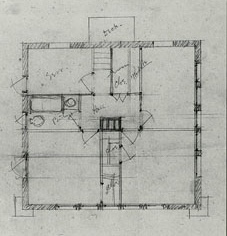

Above, left: Wright’s first-floor plan, scheme one. Above, right: Wright’s second-floor plan, scheme one. Holzhueter, “Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp” (1990), 19. Above, left: Lamp House first-floor plan, scheme two. Above, right: Lamp House second-floor plan, scheme two. Holzhueter, “Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp” (1990), 20.

Above, left: Lamp House first-floor plan, scheme two. Above, right: Lamp House second-floor plan, scheme two. Holzhueter, “Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp” (1990), 20.

Above, left: Lamp House plans, sections, details. Above, right: Lamp House elevations. Holzhueter, “Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp” (1990), 21. All of the above are preliminary drawings; they demonstrate Wright’s creative process, not the final result. For a more nuanced comparison between these drawings and the actual, constructed Lamp House, see Holzhueter, “Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp” (1990).

Above, left: Lamp House plans, sections, details. Above, right: Lamp House elevations. Holzhueter, “Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp” (1990), 21. All of the above are preliminary drawings; they demonstrate Wright’s creative process, not the final result. For a more nuanced comparison between these drawings and the actual, constructed Lamp House, see Holzhueter, “Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp” (1990).

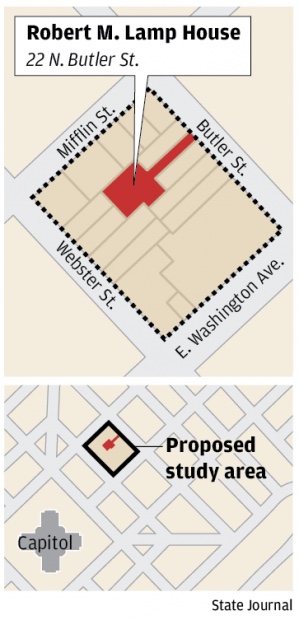

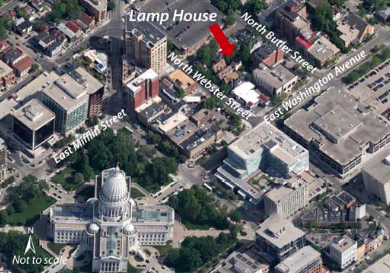

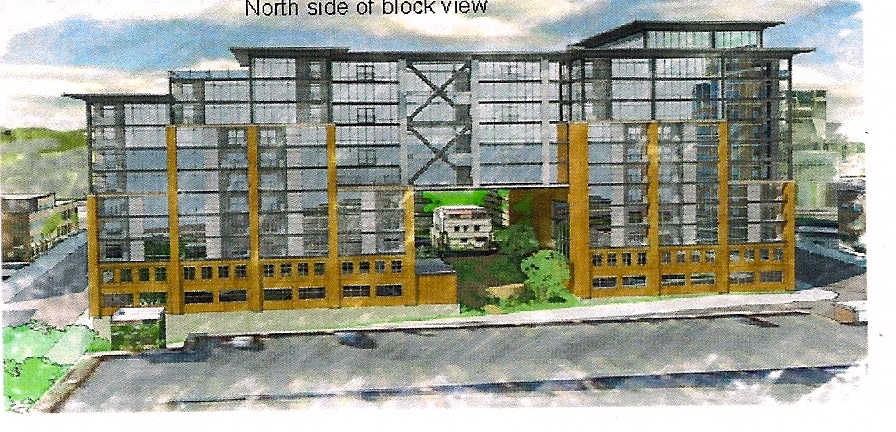

Situated in the middle of a city block, the Lamp House is bounded by East Washington Avenue and North Webster, East Mifflin, and North Butler Streets, and guarded by landscaping, fences, and other houses.[14] One enters the property from Butler street, through a narrow, ascending driveway between two houses, up a short flight of concrete steps, onto a narrow concrete walkway to the house’s northeast façade. The Lamp House remains “the historic centerpiece” of the block, surrounded by homes in the Queen Anne, Italianate, and Mediterranean styles.[15] Lamp’s goal was to “screen”[16] his house from the urban street using other houses, and the Lamp House continues to retain an “aura of quiet seclusion and privacy” today.[17]

Above, left: Map of the Lamp House in relation to its block and to the Capitol. The Lamp House property is indicated in red. From the Wisconsin State Journal, http://host.madison.com/robert-m-lamp-house-map/image_228bd0ca-21a2-5eb4-8aaf-b6ec5e4760b0.html. Above, right: Aerial view of the State Capitol and the Lamp House block, prior to the demolitions on Webster Street in 2014. Report of the Lamp House Block Ad Hoc Committee, 5.

Above, left: Map of the Lamp House in relation to its block and to the Capitol. The Lamp House property is indicated in red. From the Wisconsin State Journal, http://host.madison.com/robert-m-lamp-house-map/image_228bd0ca-21a2-5eb4-8aaf-b6ec5e4760b0.html. Above, right: Aerial view of the State Capitol and the Lamp House block, prior to the demolitions on Webster Street in 2014. Report of the Lamp House Block Ad Hoc Committee, 5.

Above, left: View of the Lamp House through two houses on Butler Street. http://www.prairiemod.com/features/2009/11/connect-shedding-some-light-on-the-lamp-house-plans.html. Above, right: Approaching the Lamp House from Butler Street. The house was originally designed with an oblique, rather than straight, approach, until Lamp bought and modified the site’s facing property in 1904. Photograph by Christopher J. Slaby, February 2016.

Above, left: View of the Lamp House through two houses on Butler Street. http://www.prairiemod.com/features/2009/11/connect-shedding-some-light-on-the-lamp-house-plans.html. Above, right: Approaching the Lamp House from Butler Street. The house was originally designed with an oblique, rather than straight, approach, until Lamp bought and modified the site’s facing property in 1904. Photograph by Christopher J. Slaby, February 2016.

The house’s brick exterior was originally yellow or cream-colored, of a type indigenous to Wisconsin, but has since been painted white.[18] The house’s four corners are bounded by dentilated pilasters that truncate at the middle of the second story, and the upper parapet is also adorned with a dentilated cornice. The Lamp House was originally only two stories high, and this parapet contained a roof garden and wooden pergola. In September 1913, Lamp had the roof garden enclosed as a playroom for his new stepson,[19] and the remaining pergola structure was removed in November 1961.[20] The resultant, third-floor penthouse is flat-roofed, lightly constructed, and surrounded with a nearly continuous band of simple windows.[21] All the windows in the original stories are leaded casement, with diamond-shaped glass panes, surrounded by thin borders of white, translucent glass.[22] The windows open outward, and are framed with red cypress on both the interior and exterior.[23]

The house’s brick exterior was originally yellow or cream-colored, of a type indigenous to Wisconsin, but has since been painted white.[18] The house’s four corners are bounded by dentilated pilasters that truncate at the middle of the second story, and the upper parapet is also adorned with a dentilated cornice. The Lamp House was originally only two stories high, and this parapet contained a roof garden and wooden pergola. In September 1913, Lamp had the roof garden enclosed as a playroom for his new stepson,[19] and the remaining pergola structure was removed in November 1961.[20] The resultant, third-floor penthouse is flat-roofed, lightly constructed, and surrounded with a nearly continuous band of simple windows.[21] All the windows in the original stories are leaded casement, with diamond-shaped glass panes, surrounded by thin borders of white, translucent glass.[22] The windows open outward, and are framed with red cypress on both the interior and exterior.[23]

Left: Northeast façade including roof garden and pergola. Robert Lamp standing in front of pilaster; stepson Fay Shaw standing in planter. Photograph from estate of Lorraine Lamp, daughter-in-law of Robert Lamp, ca. 1912, 4 x 6.25 inches, Wisconsin Historical Society. Holzhueter, “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp” (Winter 1988-1989), 124.

The house’s exterior focal point is the northeast façade. It includes a concrete, half-turn staircase, which forms a terrace bounded by parapet walls, and leads to an enclosed entry porch made of red cypress on the northwest wall. The façade’s first story features three sets of double windows of equal size, evenly spaced. Two diamond-shaped brick patterns adorn the walls between them, imitating the diamond patterns of the window panes.[24] The façade’s second story has five narrow windows, unevenly but symmetrically spaced, resting on a sill of five corbeled brick courses. Three corbeled brick courses run horizontally across the façade at the levels of the first-story window sills and lintels, and the second-story window lintels. The façade also includes a double window at the basement level.

Above, left: Northeast façade, terrace, facing northwest. Photograph by James Bellucci, May 2016. Above, right: Interior of northwest porch, facing southwest. https://www.abodo.com/madison-wi/22-n-butler-st.

Above, left: Northeast façade, terrace, facing northwest. Photograph by James Bellucci, May 2016. Above, right: Interior of northwest porch, facing southwest. https://www.abodo.com/madison-wi/22-n-butler-st. Above: Northeast façade details: dentils on pilasters and cornice, corbeled brick courses, diamonds on window mullions. From the Lamp House Ad Hoc Plan Committee’s site tour, https://madison.legistar.com/View.ashx?M=F&ID=2734367&GUID=8D27C25A-0095-492A-A407-4AA8CAC4D0A8.

Above: Northeast façade details: dentils on pilasters and cornice, corbeled brick courses, diamonds on window mullions. From the Lamp House Ad Hoc Plan Committee’s site tour, https://madison.legistar.com/View.ashx?M=F&ID=2734367&GUID=8D27C25A-0095-492A-A407-4AA8CAC4D0A8.

Above the northwest porch, on the second floor, are three narrow, equally spaced bedroom windows. Two corbeled brick courses run horizontally at the level of the window sills and lintels. The rear, southwest wall features a small airing porch between the first and second floors. The porch is constructed of red cypress and supported by two brick piers of the same style as the house’s corner pilasters. The rear, southwest wall also includes door and two windows on the first floor; a narrow window on the second floor; and two narrow windows between the second and third floors. Finally, the southeast wall includes a projecting bay and double window on the first floor, and three windows on the second floor. The southwest and southeast walls are conjoined by a total of four corbeled brick courses at the level of the first and second-floor window sills and lintels.

Above, left: Northwest wall with enclosed porch, facing south. Above, right: Northwest wall with enclosed porch, southwest wall with airing porch, facing southeast. Both photographs are from the Lamp House Ad Hoc Plan Committee’s site tour, https://madison.legistar.com/View.ashx?M=F&ID=2734367&GUID=8D27C25A-0095-492A-A407-4AA8CAC4D0A8.

Above, left: Northwest wall with enclosed porch, facing south. Above, right: Northwest wall with enclosed porch, southwest wall with airing porch, facing southeast. Both photographs are from the Lamp House Ad Hoc Plan Committee’s site tour, https://madison.legistar.com/View.ashx?M=F&ID=2734367&GUID=8D27C25A-0095-492A-A407-4AA8CAC4D0A8.

Holzhueter describes the central living areas as “inviting” and “comfortable,” appearing larger than their dimensions would suggest, and successful “both aesthetically and practically.”[25] The four-foot-wide entry door reveals an open space, with a wood floor, in which the living and dining rooms flow into one another, without being divided by a door or hallway, thus forming an L-shape.[26] The two rooms “pivot” on a living room wall consisting of built-in bookcases and a centralized, red-brick hearth.[27] The base of the fireplace is triangular. On the facing, northeast wall, light shines through the façade’s three sets of double casement windows, whose vertical frames run from the lintel to the floor. On the conjoining, southwest wall, the bay window is set into a shallow, wood-paneled recess stepped about a foot above the floor. The opposite, northwest dining room wall contains three sets of casement window-doors (or French doors), which open to the enclosed porch. The living and dining rooms are united by continuous, horizontal bands of red cypress woodwork, which attach at the level of the window lintels. According to Wright, the horizontal wood bands give the impression of “generous overhead even to small rooms.”[28] The woodwork also frames interior decorations and furniture.[29]

Above, left: View through enclosed porch to main entry door, facing southeast. Photograph by James Bellucci, May 2016. Above, right: Interior of main entry door and double casement window, facing north. Photograph by James Bellucci, May 2016.

Above, left: View through enclosed porch to main entry door, facing southeast. Photograph by James Bellucci, May 2016. Above, right: Interior of main entry door and double casement window, facing north. Photograph by James Bellucci, May 2016.

Above, left: View through main entry door to living room with central hearth and bay recess, facing southeast. https://www.abodo.com/madison-wi/22-n-butler-st. Above, right: Living room and dining room, facing south, with period furnishings. Photograph in Chazen Museum of Art. From Holzhueter, “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp” (Winter 1988-1989), 113.

Above, left: View through main entry door to living room with central hearth and bay recess, facing southeast. https://www.abodo.com/madison-wi/22-n-butler-st. Above, right: Living room and dining room, facing south, with period furnishings. Photograph in Chazen Museum of Art. From Holzhueter, “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp” (Winter 1988-1989), 113.

Above, left: Living room, hearth, dining room wall with entry door and window-doors, facing northwest. https://www.abodo.com/madison-wi/22-n-butler-st. Above, right: Dining room, hearth wall, balustrade, window-doors, facing southwest. https://www.abodo.com/madison-wi/22-n-butler-st.

Above, left: Living room, hearth, dining room wall with entry door and window-doors, facing northwest. https://www.abodo.com/madison-wi/22-n-butler-st. Above, right: Dining room, hearth wall, balustrade, window-doors, facing southwest. https://www.abodo.com/madison-wi/22-n-butler-st.

Above, left: Dining room, view of living room casement windows and balustrade, facing east. https://www.abodo.com/madison-wi/22-n-butler-st. Above, right: Window-door in dining room, facing northwest. Photograph by Stephanie M. Klem, February 2016.

Above, left: Dining room, view of living room casement windows and balustrade, facing east. https://www.abodo.com/madison-wi/22-n-butler-st. Above, right: Window-door in dining room, facing northwest. Photograph by Stephanie M. Klem, February 2016.

An open staircase separates the dining room from the kitchen. The continuous, half-turn staircase is adorned with a horizontal balustrade facing the living room. The balustrade consists of vertical wood balusters that alternate in size and shape – between large, cubical, and pointed outward, and small, rectangular, pointed inward. In the stairwell, wood paneling crawls up the walls, parallel to the outline of each stair, thus forming a zigzag pattern. The stairwell has little headroom, and its half-space landings are lighted with casement windows, including on the door opening to the rear airing porch. Wright may have designed the wide first-floor entry door and the well-lit stair landings in order to accommodate Lamp’s mobility aids like canes and crutches.[30]

Above, left: Balustrade and dining room wall, facing southeast. Photograph by Stephanie M. Klem, February 2016. Above, right: Kitchen, facing southwest. https://www.abodo.com/madison-wi/22-n-butler-st.

Above, left: Balustrade and dining room wall, facing southeast. Photograph by Stephanie M. Klem, February 2016. Above, right: Kitchen, facing southwest. https://www.abodo.com/madison-wi/22-n-butler-st.

Above, left: Detail of balustrade, facing southeast. Photograph by Katie Liu, February 2016. Above, right: Detail of staircase and balustrade, facing southwest. Photograph by James Bellucci, May 2016.

Above, left: Detail of balustrade, facing southeast. Photograph by Katie Liu, February 2016. Above, right: Detail of staircase and balustrade, facing southwest. Photograph by James Bellucci, May 2016.

Above, left: Staircase and balustrade, facing northeast. Photograph by Stephanie M. Klem, February 2016. Center: Staircase and door to airing porch, facing southwest. Photograph by Stephanie M. Klem, February 2016. Above, right: Hallway, second floor, facing northeast. Photograph by Stephanie M. Klem, February 2016. Below, right: Bedroom interior, second floor. https://www.abodo.com/madison-wi/22-n-butler-st.

Above, left: Staircase and balustrade, facing northeast. Photograph by Stephanie M. Klem, February 2016. Center: Staircase and door to airing porch, facing southwest. Photograph by Stephanie M. Klem, February 2016. Above, right: Hallway, second floor, facing northeast. Photograph by Stephanie M. Klem, February 2016. Below, right: Bedroom interior, second floor. https://www.abodo.com/madison-wi/22-n-butler-st.

The second floor features a narrow, irregularly shaped corridor in the center, surrounded by four bedrooms and one bathroom. The bedrooms’ window woodwork and continuous, horizontal wood banding is like that of the first floor. The third-floor penthouse, which Wright did not design, contains a central, white-brick fireplace; a narrow, partially enclosed garden facing southwest; and French doors separating the penthouse entry from its main den. The entry contains hook-ups for kitchen appliances, and the penthouse contains a bathroom.

The second floor features a narrow, irregularly shaped corridor in the center, surrounded by four bedrooms and one bathroom. The bedrooms’ window woodwork and continuous, horizontal wood banding is like that of the first floor. The third-floor penthouse, which Wright did not design, contains a central, white-brick fireplace; a narrow, partially enclosed garden facing southwest; and French doors separating the penthouse entry from its main den. The entry contains hook-ups for kitchen appliances, and the penthouse contains a bathroom.

Above, left: Second floor hallway and half-turn staircase, facing southwest. Photograph by Stephanie M. Klem, February 2016. Above, center: Cat enjoying half-landing between second and third floors; detail of woodwork and casement window, facing southwest. Photograph by James Bellucci, May 2016. Above, right: Staircase and second floor hallway, facing northeast. Photograph by Stephanie M. Klem, February 2016.

Above, left: Second floor hallway and half-turn staircase, facing southwest. Photograph by Stephanie M. Klem, February 2016. Above, center: Cat enjoying half-landing between second and third floors; detail of woodwork and casement window, facing southwest. Photograph by James Bellucci, May 2016. Above, right: Staircase and second floor hallway, facing northeast. Photograph by Stephanie M. Klem, February 2016.

Above, left: Third floor staircase, facing southwest. Photograph by Stephanie M. Klem, February 2016. Above, center: Third floor entry vestibule, facing northeast. Photograph by Stephanie M. Klem, February 2016. Above, right: Third floor entry vestibule with kitchen appliances (now removed), facing southwest. https://www.abodo.com/madison-wi/22-n-butler-st.

Above, left: Third floor staircase, facing southwest. Photograph by Stephanie M. Klem, February 2016. Above, center: Third floor entry vestibule, facing northeast. Photograph by Stephanie M. Klem, February 2016. Above, right: Third floor entry vestibule with kitchen appliances (now removed), facing southwest. https://www.abodo.com/madison-wi/22-n-butler-st.

Above, left: Third floor, fireplace, windows, greenhouse, facing southeast. https://www.abodo.com/madison-wi/22-n-butler-st. Above, right: Third floor, continuous windows, view of neighboring houses and Lake Mendota, facing north. https://www.abodo.com/madison-wi/22-n-butler-st.

Above, left: Third floor, fireplace, windows, greenhouse, facing southeast. https://www.abodo.com/madison-wi/22-n-butler-st. Above, right: Third floor, continuous windows, view of neighboring houses and Lake Mendota, facing north. https://www.abodo.com/madison-wi/22-n-butler-st.

The Lamp House does not constitute a single architectural style. Instead, it exemplifies a transition between Wright’s “earlier and more mature work.”[31] Wright described the style as “New American.”[32] The Lamp House contains elements of the Arts and Crafts movement (locally sourced materials, simplified interior details, and a communal, central hearth); Gothic revival (leaded casement windows, diamond patterning, and fortress-like parapets); neoclassicism (dentils, corbeling, and the northeast façade’s second-floor window pattern);[33] Vienna Secessionist (geometric simplicity and proportionality of northeast façade);[34] Chicago School (verticality and top-heaviness); Prairie School (open floor plan and continuous, horizontal woodwork); and Japanese (roof garden and pergola that supported vines and plants).[35] Many of the house’s Gothic and neoclassical features might actually be attributed to Walter Burley Griffin, an important employee in Wright’s Oak Park Studio who assisted Wright in the summer of 1903 while he was preoccupied with other projects.[36] The Lamp House also exemplifies Wright’s initial steps toward abstraction. The preeminent architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock (1903-1987) labeled the Lamp House one of Wright’s “fundamentally square houses,” which have the “virtues of compactness and ingenuity, even though they are sometimes rather dull and formal.”[37] Holzhueter considers the Lamp House “Wright’s first mastery of the cube as a shape.”[38] Finally, the Lamp House exemplifies Wright’s goal of producing compact, affordable housing for the populace, which would concern him for the rest of his career.[39] Wright experimented with similarly open floor plans pivoting around central fireplaces in his own Home and Studio (1889). As noted above, he also proposed this type of plan in his famous “Fireproof House for $5000” article in the Ladies Home Journal in 1906.[40] Thus, the Lamp House embodies multiple styles and principles, and is not easily categorized.

Above, left: Frank Lloyd Wright, “A Fireproof House for $5000,” Ladies Home Journal (April 1907): 24. Image from Holzhueter, “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp” (Winter 1988-1989), 116. Above, right: Wright’s first and second-floor plans from “A Fireproof House for $5000,” http://www.antiquehomestyle.com/plans/lhj/1907/flw0407-fireproof.htm. Wright experimented with open floor plans in the Lamp House before publishing this article four years later. The goal was to create compact, affordable housing for the masses.

Above, left: Frank Lloyd Wright, “A Fireproof House for $5000,” Ladies Home Journal (April 1907): 24. Image from Holzhueter, “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp” (Winter 1988-1989), 116. Above, right: Wright’s first and second-floor plans from “A Fireproof House for $5000,” http://www.antiquehomestyle.com/plans/lhj/1907/flw0407-fireproof.htm. Wright experimented with open floor plans in the Lamp House before publishing this article four years later. The goal was to create compact, affordable housing for the masses.

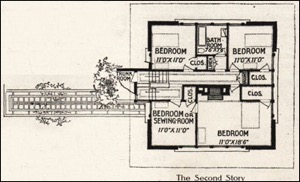

The Lamp House Debate: Preservation versus Progress

Throughout the process of designing and constructing the Lamp House, Wright appeased his long-time friend and patron by prioritizing the Lamp House site and vistas. The unique siting of the Lamp House posed creative challenges for the architect. More than a century later, the house’s siting continues to cause problems for developers, neighbors, and preservationists in the city of Madison. Real estate companies have responded to the city’s growing population by proposing apartment and hotel projects in and around the Lamp House site. The local community has taken issue with these proposals for a number of reasons; in particular, construction would fundamentally alter the nature of the Lamp House, a historic landmark significant for its site and views of the lakes. The following section will consider a few of these development proposals, the community’s responses, and the formation of the Lamp House Block Ad Hoc Committee. Indeed, the Committee’s research on the Lamp House has been fundamental to the making of this chapter. The Lamp House, once a site of pleasure and solitude, has become a site of argument and controversy over issues of economic development and cultural preservation.

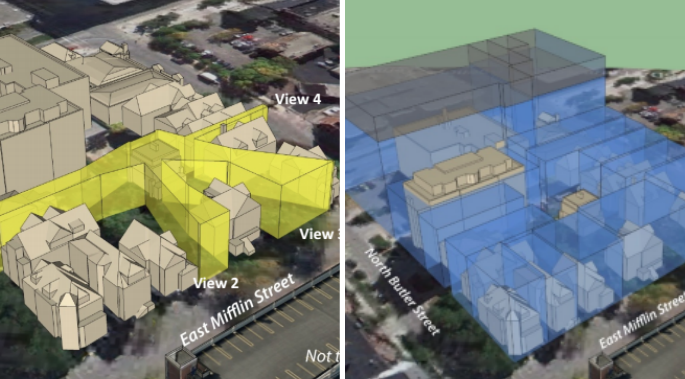

In 2005, the Lamp House was purchased by Apex Enterprises, a real estate development company led by Bruce Bosben.[41] In 2009, Apex designed a number of concepts for condominiums, apartments, and parking garages to be located near the Lamp House on the 200 block of East Mifflin Street.[42] Apex presented these proposals to a steering committee composed of neighbors concerned about development on their block. In one option, a nine-story building and a twelve-story building would be built on either side of the Lamp House. In a second option, illustrated above, these two towers would connect over and around the Lamp House. A third option would relocate the Lamp House closer to Webster Street, and potentially restore it as a visitor center, museum, or guest house, in order to make way for a twelve-story tower on Mifflin. Neighbors strongly opposed all these proposals, calling them “foolish,” “disrespectful,” and “insane,” fearing they would lower property values, disrupt views, threaten the neighborhood’s historic charm, and destroy Wright’s intentional siting of the Lamp House.[43]

Apex abandoned its proposals, and the Lamp House block escaped major redevelopment plans until 2013. That year, the Alexander Company proposed a ten-story hotel on the corner of East Washington and North Webster, the long-time site of the Pahl Tire Company.[44] Additionally, the developer Fred Rouse planned and succeeded in demolishing four of the block’s historic houses in favor of a six-story, eight million dollar apartment building, built in 2014.[45] Bosben, the Apex president and Lamp House owner, stated that redevelopment would not impair the site’s historic significance.[46] In fact, “I don’t think six stories is tall enough,”[47] he told The Capital Times, arguing that a larger structure would generate millions more in future property taxes for the City. Thus, the developers argued that redevelopment would boost the local economy and the city’s finances.

Responding to these threats to the Lamp House in the autumn of 2013, Alder Ledell Zellers recommended that an ad hoc committee advise the City on the Lamp House block.[48] Certain developers and property owners called this action “bad precedent,” complained that the City already had too many building regulations, and argued that the City’s newly instituted Downtown Plan and Zoning Code were supposed to prevent this sort of unpredictability.[49] Meanwhile, preservationist groups such as the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy, the Madison Trust for Historic Preservation, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and Frank Lloyd Wright Wisconsin lauded efforts to protect the Lamp House.[50]

Above, left: John O. “Jack” Holzhueter, journalist and historian. Cropped from photograph at http://www.railphoto-art.org/center-receives-rlhs-article-award/. Above, right: Nan Fey, former chair of the City of Madison Planning Commission. http://uufdc.org/2014/03/march-30-nan-fey/. Jack Holzhueter and Nan Fey played significant roles on the Lamp House Block Ad Hoc Plan Committee.

Above, left: John O. “Jack” Holzhueter, journalist and historian. Cropped from photograph at http://www.railphoto-art.org/center-receives-rlhs-article-award/. Above, right: Nan Fey, former chair of the City of Madison Planning Commission. http://uufdc.org/2014/03/march-30-nan-fey/. Jack Holzhueter and Nan Fey played significant roles on the Lamp House Block Ad Hoc Plan Committee.

In September 2013, the City of Madison’s Mayor and the Common Council created the Lamp House Block Ad Hoc Plan Committee. The Committee considered a broad range of issues – including area redevelopment, preservation, the economic potential of heritage tourism, and the character and scale of the neighborhood – in order to form conclusions about the block’s historical and contemporary contexts. The Committee was composed of two Common Council members, as well as six citizens with significant knowledge of Wright, architecture, cultural resources, the neighborhood, and downtown development.[51] The Committee was in good hands: among its members was John O. “Jack” Holzhueter, an historian and journalist cited throughout this chapter. Holzhueter is responsible for most of what is known about the Lamp House: he studied the Lamp House for more than five decades, lived in the Lamp House as a tenant in the 1960s, performed research and interviews in Wisconsin and at Taliesin West, and submitted the nominations for the Lamp House’s historic landmark status. The Committee worked “at warp speed” by government standards, according to Nan Fey, a member of the Committee and former chair of the City of Madison Planning Commission.[52]

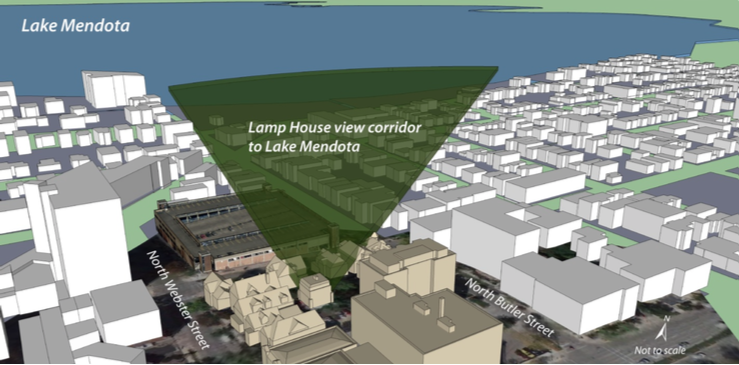

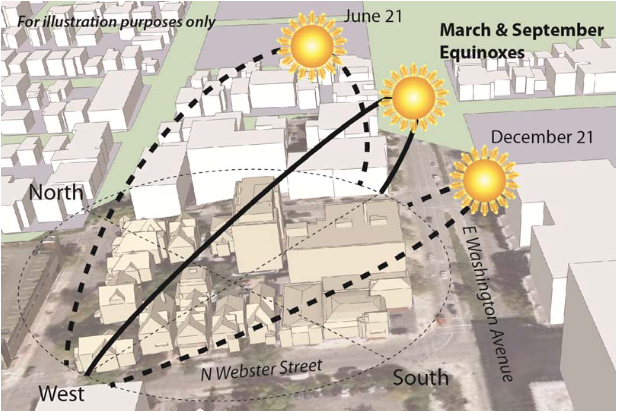

Before finalizing its report, the Committee held seven meetings between October 2013 and January 2014, during which it toured the Lamp House block and site, held a public design workshop, and made recommendations with 3D models.[53] The Committee used an interactive, scaled base model of the block to test different development schemes, views, and shadow impacts. It also considered the site’s interaction with adjacent buildings, whose rear walls constitute an “outdoor room” in which the Lamp House sits. The City’s Preservation Planner used building surveys, records, and preservation files in order to evaluate the significance of each of the properties on the block, which was deemed a “rare downtown enclave” of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century structures. The Committee prioritized each of the views from the street to the house, and evaluated the historical significance of the house’s remaining view to Lake Mendota. The Committee also considered the Zoning Code’s maximum building heights and area footprints, which allowed a substantial amount of new development to the site.

In its final recommendations, the Committee sought to “encourage redevelopment while preserving important cultural resources.”[54] The goal was to maintain the Lamp House’s access to sunlight and views of the lake and “outdoor room,” since these elements were fundamental to Wright’s original designs for the home. In order to enhance the historic character of the Lamp House and the entire block, the Committee recommended maintaining the current setback of the outdoor room’s rear façades, using high-quality architectural materials and darker tones, minimizing massing, allowing gaps between buildings, concealing mechanical equipment and utilities, and attending to landscaping. Significantly, the Committee suggested that the East Mifflin and North Butler Street blocks be preserved as historic districts, and noted that property owners could then receive tax credit incentives for repair and maintenance. Throughout its report, the Committee emphasized significant economic opportunities for the Lamp House within the heritage tourism industry. The report concluded, “These recommendations seek to ensure that in the future, both the Lamp House and its context will contribute to a thoughtful and vibrant built environment that could be a model for balancing redevelopment and preservation in the City of Madison.”[55]

Above, left: View of Victorian houses on Mifflin Street, facing southeast; the Lamp House sits behind them. Created with Google Street View. Above, center: View from Mifflin Street to the Lamp House’s enclosed porch on the northwest wall. Photograph by Christopher J. Slaby, February 2016. Above, right: View from Mifflin Street to the Lamp House’s northwest enclosed porch and southwest airing porch. Photograph by Christopher J. Slaby, February 2016.

Above, left: View of Victorian houses on Mifflin Street, facing southeast; the Lamp House sits behind them. Created with Google Street View. Above, center: View from Mifflin Street to the Lamp House’s enclosed porch on the northwest wall. Photograph by Christopher J. Slaby, February 2016. Above, right: View from Mifflin Street to the Lamp House’s northwest enclosed porch and southwest airing porch. Photograph by Christopher J. Slaby, February 2016.

Above, left: View from third floor to front yard, facing northeast toward Butler Street. Lamp would have been able to see Lake Monona from the third floor, but the view is now obscured by apartment buildings. Photograph by James Bellucci, May 2016. Above, right: View of front yard landscaping from northeast terrace. Photograph by James Bellucci, May 2016.

Above, left: View from third floor to front yard, facing northeast toward Butler Street. Lamp would have been able to see Lake Monona from the third floor, but the view is now obscured by apartment buildings. Photograph by James Bellucci, May 2016. Above, right: View of front yard landscaping from northeast terrace. Photograph by James Bellucci, May 2016.

The Report of the Lamp House Ad Hoc Plan Committee was finalized on January 14, 2014, accepted by the Common Council on February 25, 2014, and adopted as a supplement to the City of Madison’s Downtown Plan on March 4, 2014. It should be noted that city plans are simply guides or suggestions; they reflect “important community values,” according to Nan Fey, but are not actually laws or ordinances.[56] That is why it was possible for the developer North Central Group to ignore the City of Madison’s recommendations in the Lamp House Block Plan, the Downtown Plan, and the Comprehensive Plan. The developer bought the Alexander Company’s 2014 plans to replace the site of the Pahl Tire Company, and on August 26, 2015, it began work on the new ten-story Marriott AC Hotel Madison. In an editorial to the Wisconsin State Journal, Nan Fey lamented that, “a building designed to complement, support and respect the future economic value of heritage tourism on this unique block could have won enthusiastic approval,” but instead, this hotel would “further shade the landmark Lamp House and likely be cited as precedent by the next developer who wants to avoid complying with block plan recommendations along East Washington Avenue.”[57] One of the purposes of city plans is to encourage strong design. Yet, developers have refused to satisfy the Report of the Lamp House Block Ad Hoc Committee, despite the report’s thorough planning and research.

As it stands today, the Lamp House continues to replicate some of the experiences Wright and Lamp envisioned: it towers over neighboring homes from its artificially raised platform, retains spectacular views of Lake Mendota, and enjoys quiet and seclusion from the congested streets surrounding it. Because of recent construction, however, the Lamp House is shielded from Lake Monona and from much of the natural sunlight it once enjoyed. The Report of the Lamp House Block Ad Hoc Committee offers an appealing argument for preserving the Lamp House and its site. Redevelopment is not the only or the most profitable means of boosting the local economy. If the Committee’s report is followed, the Madison community could improve its economy by turning the Lamp House into a heritage tourist destination. In the meantime, the destiny of the Lamp House remains unclear.

Notes

- Report of the Lamp House Ad Hoc Plan Committee, City of Madison, Wisconsin, January 2014, http://www.cityofmadison.com/planning/documents/adhoclamphouse.pdf, 4. ↵

- John O. Holzhueter, “Nomination Form for Robert M. Lamp House,” National Register of Historical Places Inventory, National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior, January 3, 1978. For more on Robert Lamp’s biography and personal relationship with Wright, see John O. Holzhueter, “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 72 (Winter 1988-1989): 83-125; and John O. Holzhueter, “Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp,” in Frank Lloyd Wright and Madison: Eight Decades of Artistic and Social Interaction, ed. Paul E. Sprague (Madison, WI: Elvehjem Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1990), 13-27. Lamp also commissioned Rocky Roost, a summer cottage on Lake Mendota, from Wright in 1893. ↵

- Frank Lloyd Wright, Frank Lloyd Wright, An Autobiography (New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1943), 31-32, 52. Cited in Holzhueter, “Nomination Form for Robert M. Lamp House.” ↵

- Report of the Lamp House Ad Hoc Plan Committee, 4. ↵

- Report of the Lamp House Ad Hoc Plan Committee, 4. ↵

- Madison Democrat, September 6, 1903. Cited in Holzhueter, “Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp,” 18. ↵

- Report of the Lamp House Ad Hoc Plan Committee, 4. ↵

- Report of the Lamp House Ad Hoc Plan Committee, 4. ↵

- Report of the Lamp House Ad Hoc Plan Committee, 4. ↵

- Report of the Lamp House Ad Hoc Plan Committee, 4. ↵

- Dean Mosiman, “City Mulls Special Committee for Frank Lloyd Wright House Block,” Wisconsin State Journal, September 12, 2013, http://host.madison.com/news/local/govt-and-politics/city-mulls-special-committee-for-frank-lloyd-wright-house-block/article_0166a771-246a-5b73-b64f-0e13e5058889.html. ↵

- “22 N Butler St,” Trulia, http://www.trulia.com/homes/Wisconsin/Madison/sold/420033-22-N-Butler-St-Madison-WI-53703. ↵

- Holzhueter, “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp,” 19. ↵

- Holzhueter, “Nomination Form for Robert M. Lamp House.” ↵

- Report of the Lamp House Ad Hoc Plan Committee, 14. ↵

- Holzhueter, “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp,” 20. ↵

- Holzhueter, “Nomination Form for Robert M. Lamp House.” ↵

- Holzhueter, “Nomination Form for Robert M. Lamp House.” ↵

- “Robert Lamp House,” Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, http://www.flwright.org/researchexplore/wrightbuildings/robertlamphouse. ↵

- Holzhueter, “Nomination Form for Robert M. Lamp House.” ↵

- Holzhueter, “Nomination Form for Robert M. Lamp House.” ↵

- Holzhueter, “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp,” 20. ↵

- Holzhueter, “Nomination Form for Robert M. Lamp House.” ↵

- “Robert Lamp House,” Frank Lloyd Wright Trust. ↵

- Holzhueter, “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp,” 20. ↵

- Holzhueter, “Nomination Form for Robert M. Lamp House.” ↵

- Holzhueter, “Nomination Form for Robert M. Lamp House.” ↵

- Wright, An Autobiography, 45. Cited in Holzhueter, “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp,” 20. ↵

- Holzhueter, “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp,” 20. ↵

- Holzhueter, “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp,” 20. ↵

- Report of the Lamp House Ad Hoc Plan Committee, 4. ↵

- Mosiman, “City Mulls Special Committee for Frank Lloyd Wright House Block.” ↵

- Holzhueter, “Nomination Form for Robert M. Lamp House.” ↵

- Holzhueter, “Nomination Form for Robert M. Lamp House.” ↵

- Report of the Lamp House Ad Hoc Plan Committee, 4. ↵

- Holzhueter, “Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp,” 18. ↵

- Henry-Russell Hitchcock, In the Nature of Materials (New York: Da Capo Press, 1973), 44. Cited in Holzhueter, “Nomination Form for Robert M. Lamp House.” ↵

- Holzhueter, “Nomination Form for Robert M. Lamp House.” ↵

- Holzhueter, “Nomination Form for Robert M. Lamp House.” Report of the Lamp House Ad Hoc Plan Committee, 4. ↵

- Holzhueter, “Nomination Form for Robert M. Lamp House.” ↵

- Mike Ivey, “Lamp House Owner OK with High-Rise Next to Frank Lloyd Wright Building,” The Capital Times, November 26, 2013, http://host.madison.com/ct/news/local/writers/mike_ivey/lamp-house-owner-ok-with-high-rise-next-to-frank/article_12732f8c-561f-11e3-ae68-0019bb2963f4.html. ↵

- Tarr, “Residents Irritated at Developer’s Plans for East Mifflin, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Lamp House.” ↵

- Tarr, “Residents Irritated at Developer’s Plans for East Mifflin, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Lamp House.” ↵

- Mosiman, “City Mulls Special Committee for Frank Lloyd Wright House Block.” ↵

- Mosiman, “City Mulls Special Committee for Frank Lloyd Wright House Block.” ↵

- Ivey, “Lamp House Owner OK with High-Rise Next to Frank Lloyd Wright Building.” ↵

- Ivey, “Lamp House Owner OK with High-Rise Next to Frank Lloyd Wright Building.” ↵

- Mosiman, “City Mulls Special Committee for Frank Lloyd Wright House Block.” ↵

- Mosiman, “City Mulls Special Committee for Frank Lloyd Wright House Block.” ↵

- Michael Bridgeman, “Preserving the Lamp House,” Wright in Wisconsin 19 (2014): 7. ↵

- Report of the Lamp House Ad Hoc Plan Committee, 3. ↵

- Private discussion with Nan Fey, February 10, 2016. ↵

- Report of the Lamp House Ad Hoc Plan Committee. ↵

- Report of the Lamp House Block Ad Hoc Committee, 23. ↵

- Report of the Lamp House Block Ad Hoc Committee, 23. ↵

- Nan Fey, “Development Approval Process is Not ‘Fussy.’” ↵

- Nan Fey, “Development Approval Process is Not ‘Fussy.’” ↵