Chapter 1: Wright’s Life and Career

The Usonian Idea (Claire MacDonald, Garen Alexander, and Chris Slaby)

Claire McDonald; Garen Alexander; and Christopher J. Slaby

Usonia is a term that was used by Frank Lloyd Wright to describe a type of housing for the American masses. Wright’s primary goal in building Usonian homes was to make them affordable for the American middle class. Post-Depression housing spread rapidly throughout the country as Americans were in desperate need of reasonably priced housing. Wright’s Usonian homes are generally modestly sized one story dwellings in suburban neighborhoods. Several houses utilize an L-shaped floor plan, separating sleeping and living areas (see Figure 1). They incorporate the natural world into their architecture, sometimes featuring gardens and outdoor terraces just beyond wall-windows. This is largely due to Wright’s belief in the close relationship between the natural world and architecture. He wanted to build homes that incorporated natural elements into his living spaces.[1]

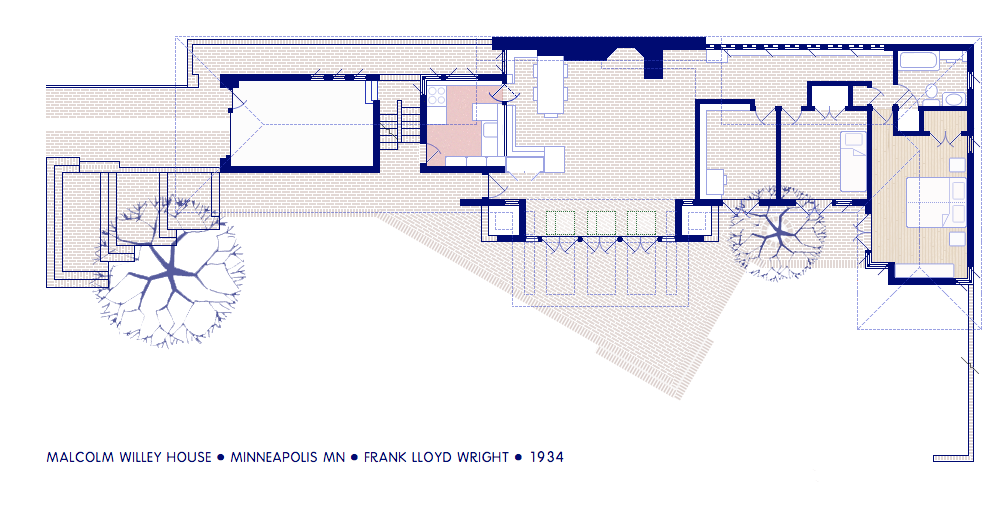

The Willey House in Minneapolis, considered a precursor to the Usonian home, demonstrates this bridge between the built and the natural worlds. Although it was a predecessor to Usonia, it combined aspects of both Prairie and Usonian style construction. Wright’s Prairie School architecture featured local building materials, a strong sense of horizontality, and an incorporation with the landscape. The Willey House was meant to be affordable, like the Usonian homes, though it was not conceived of as part of a larger scheme. Like Usonian homes, though, the Willey House featured an open floor plan. The bedrooms are grouped at one end and the living space is at the center (see Figure 2). This then opens onto the backyard, where a diagonal brick patio leads into the lawn (see Figure 3).

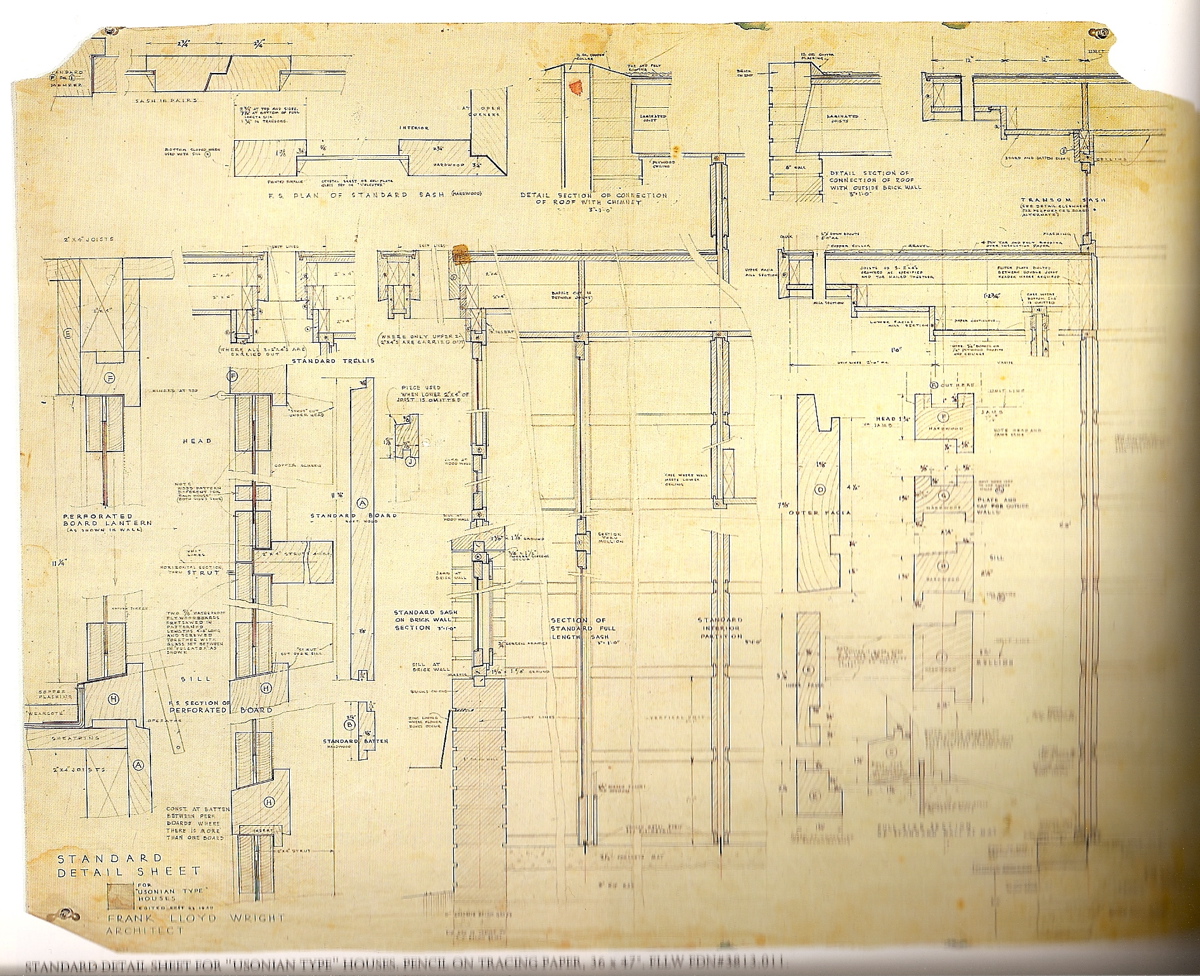

Elimination and simplification of all costly, unnecessary features of the home also affected its design, sense of space, and daily family life. One of Wright’s overarching goals in achieving this was consolidating heating, lighting, and sanitation systems. For example, underfloor heating was less expensive than central heating and was used in the majority of Usonian homes. The frugal attitude towards housing at the time complemented Wright’s uncluttered design aesthetics – he had no problem replacing a garage with a carport and leaving wood unpainted. Wright also emphasized one of his existing values of limited sleeping, storage, and kitchen space, as he envisioned the majority of the family’s activity taking place in the living room, which often flowed into the dining room (see Figure 4). The combination of this open space and condensed sleeping and kitchen areas allowed a low-cost house to serve many functions yet accommodated only residents willing to live modestly.

The initial impact and long-term legacy of Wright’s Usonian homes include failures and successes. Though Usonia aimed to solve a problem for the masses, it only resulted in a little over one hundred homes. Only a select few of the millions of Americans looking for affordable housing were thus able to find a home with Wright’s Usonian plan. In addition, Wright’s Usonian homes were seldom as affordable as originally advertised. It seems that Wright’s big thinking and notoriously bad money management doomed the Usonian project from the start. However, if we consider success in broader terms, Usonian homes did have a variety of positive impacts. For one, even if millions of Americans were not able to enjoy a Wright home, Usonia brought high-quality building and design to some in the middle class. In addition, even if this particular project was not as popular or directly powerful as Wright might have hoped, it was one of the first major attempts at bringing high architecture to everyday people. Wright was able to use his fame and his appeal to suggest that middle class homes could and should be designed with the same care and thoughtfulness as the homes of the wealthy.

A 2013 Wall Street Journal article on buying and living with Wright properties brings up the long-term implications of Usonian homes.[2] It describes current-day homeowners as “those willing to accept the challenge of owning a dwelling designed by America’s most-famous architect.” These challenges include the time, money, and effort required to maintain such buildings. The article goes on to note that despite these challenges, “[m]any owners of Wright homes believe the pleasures of dwelling in a legendary architect’s creation far outweigh any drawbacks.” While perhaps not a drawback, there is another barrier to entry in the club of current-day Usonia dwellers. Wright’s homes, even the Usonian ones originally designed to be affordable, are extremely expensive today. Wright’s Usonian Penfield House went on the market in 2014 for $1.7 million (see Figure 5).[3] The most affordable Wright home on the market right now is the Usonian Eppstein House in Galesburg, Michigan, a bargain for $455,000 (see Figure 6).[4] Yet while these prices preclude most Americans from living in a Wright home, those who do often make the choice for the sake of history. Upper-middleclass Usonian homeowners frequently purchase Wright homes out of an affinity for the architect and with the intention of shepherding the homes into the future. In that sense Wright was also successful in inspiring an enthusiasm for thoughtful home building and design. By living in and maintaining historic structures, current-day owners of Usonian homes act as stewards for the past, present, and future.

Bibliography

Larkin, David, and Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer. Frank Lloyd Wright: The Masterworks. New York: Rizzoli, 1993.

Lind, Carla. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian Houses. San Francisco: Pomegranate Artbooks, 1994.

Lublin, Joann S. “The Pleasures and Pitfalls of Frank Lloyd Wright Homes.” The Wall Street Journal. May 16, 2013.

Peterson, Spencer. “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Louis Penfield House Wants $1.7 M.” Curbed. May 27, 2014.

Rosenbaum, Alvin. Usonia: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Design for America. Washington, D.C.: Preservation Press, National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1993.

Sergeant, John. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian Houses: The Case for Organic Architecture. New York: Whitney Library of Design, 1976.

Xie, Jenny. “Frank Lloyd Wright 1953 House Asks $455K After Restoration.” Curbed. March 3, 2016.

- General information in this section on Wright’s Usonian architecture comes from David Larkin and Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, Frank Lloyd Wright: The Masterworks (New York: Rizzoli, 1993); Carla Lind, Frank Lloyd Wright's Usonian Houses (San Francisco: Pomegranate Artbooks, 1994); Alvin Rosenbaum, Usonia: Frank Lloyd Wright's Design for America (Washington, D.C.: Preservation Press, National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1993); and John Sergeant, Frank Lloyd Wright's Usonian Houses: The Case for Organic Architecture (New York: Whitney Library of Design, 1976). ↵

- Joann S. Lublin, "The Pleasures and Pitfalls of Frank Lloyd Wright Homes," The Wall Street Journal, May 16, 2013. ↵

- Spencer Peterson, "Frank Lloyd Wright's Louis Penfield House Wants $1.7 M," Curbed, May 27, 2014. ↵

- Jenny Xie, "Frank Lloyd Wright 1953 House Asks $455K After Restoration," Curbed, March 3, 2016. ↵