Chapter 1: Wright’s Life and Career

Wright’s Early Years, 1887-1901 (Stephanie and Sela)

Stephanie Klem and Sela Gordon

Introduction

When the architect Philip Johnson pronounced Wright “the greatest architect of the nineteenth century” to a group of Harvard design students in 1954 – a recurring anecdote in Wrightian lore – this remark undercut Wright’s arrogant persona, and alluded to some of Wright’s stereotypically nineteenth-century values.[1]

These values – such as romanticism, naturalism, traditionalism, and idealism[2] – were seemingly at odds with the modernist movement. Johnson’s statement reminds us that Wright’s design work began in the nineteenth century and responded to Victorian tastes, reforms, and ideals. For example, Wright’s “picturesque” design aesthetic derived from the Shingle style, which combined elements of the Queen Anne and Colonial styles, and which he learned from his first employer in Chicago, the architect Joseph Lyman Silsbee (1848-1913).[3] His next Chicago employer, the architect Louis Sullivan (1856-1924) of the firm Adler & Sullivan, inspired Wright to analyze architecture rationally, reject blind imitation of historical styles, and view the architect as the “germ” of poetic expression.[4]

Importantly, Sullivan imparted his credo of “form follows function” – that a building’s design and shape should be determined by its function, and not by historical precedent.[5] Wright adapted Sullivan’s goals for steel-framed skyscrapers to domestic design, aiming to modernize the traditional house and formulate a type reflecting local conditions of program, construction, and site.[6] In addition to ideas he got from Silsbee and Sullivan, Wright also drew inspiration from the International Arts and Crafts movement.

The Arts and Crafts Movement

The Arts and Crafts movement originated in England in the 1880s as part of a broad, ongoing movement in design reform. Earlier in the nineteenth century, reformers such as the architect and designer A.W.N. Pugin (1812-1852), and the critic and theorist John Ruskin (1819-1900), equated architectural design with issues of morality.[7] Inspired by their writings, the designer, writer, and socialist William Morris (1834-1896) put their ideas into practice. By the 1880s, Morris became an internationally renowned designer and the key figure of the Arts and Crafts movement.[8] The Arts and Crafts movement offered new principles for living and working as a means of alleviating the dishonest, ostentatious design and alienated labor resulting from industrialization.[9]

“Arts and Crafts” does not refer to a single stylistic vocabulary; indeed, American Arts and Crafts practitioners differed widely in their attitudes toward “style, history, the region, the machine, materials, nature, and how life should be lived.”[10] Instead, what linked American proponents of the Arts and Crafts movement was an attitude or approach that derived from Morris, did not rely solely on other cultural traditions, and promoted craftsmanship, simplicity, and integrity in organic art, design, and architecture.[11] The Arts and Crafts movement garnered a platform in Chicago at Jane Addams’s Hull House in October 1897 with the formation of the Chicago Arts and Crafts Society, of which Wright was a charter member. Wright would have learned about international design movements through International Expositions (Chicago in 1893, St. Louis in 1904); the London magazine The Studio, which advocated for Arts and Crafts and displayed the abstracted, stylized work of the Viennese Secessionists; America journals such as The Craftsman, House Beautiful, and Ladies Home Journal; and lectures and programs through clubs and societies.[12] Wright was personally acquainted with the English Arts and Crafts designer and spokesperson Charles Robert Ashbee (1863-1942), whom he met in 1900 during Ashbee’s lecture tour promoting England’s National Trust.[13] All these experiences were foundational to Wright’s early design work, and led to his seminal lecture, “The Art and Craft of the Machine,” in which he adapted and transformed Arts and Crafts principles.

The Art and Craft of the Machine (1901)

In the “The Art and Craft of the Machine,” delivered to the Chicago Arts and Crafts Society in 1901, Wright argues that the machine is the future of art and craft, and actually falls in line with both Arts and Crafts and democratic values.[14] Morris and many of his followers staunchly rejected the machine in favor of handicraft, so Wright’s unusual position is an example of contradictions within the American Arts and Crafts movement. Morris believed that human greed drove industrialization and turned the machine into a “terrible engine of enslavement”[15] and violence, that oppressed its laborers, wasted materials, created pollution, and took the joy out of work.[16] Wright argues, however, that the machine itself was not evil, but was in fact the victim of evil practitioners. Machines had become safer and more advanced, and could therefore be used for good, to “emancipate human expression,”[17] lengthen lifespans, and free human labor. Furthermore, he argued the machine’s accuracy and efficiency eliminated the need to conceal structures or lie about materials, prevented waste, made beautiful design available to a wider audience, and most importantly, allowed for the “highest form of simplicity.”[18] Wright called the machine a “marvelous simplifier; the emancipator of the creative mind, and in time the regenerator of the creative conscience.”[19] If Arts and Crafts advocates believed materials should reveal their true nature, it logically followed that machine-made products would express their mode of production, and would therefore look clean and rectilinear.[20]

Home and Studio, Oak Park, Illinois (1889)

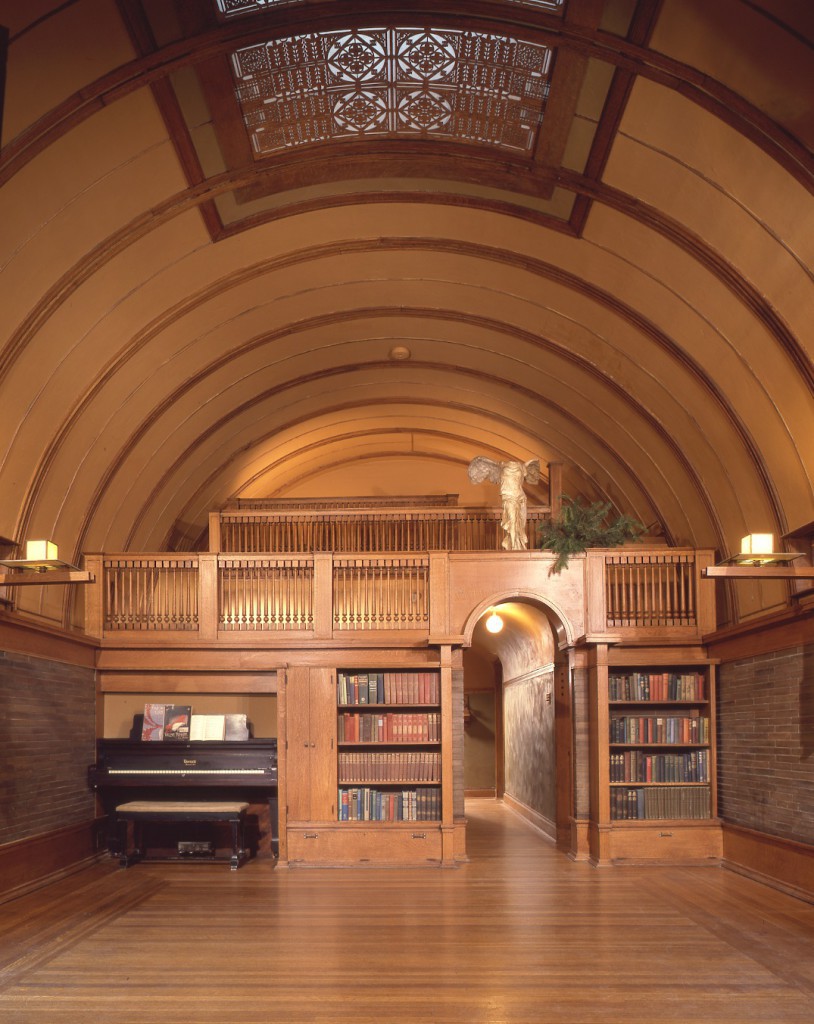

Before the Chicago Arts and Crafts Society formed in 1897, Wright was already beginning to design in ways that would later define the American Arts and Crafts movement. For example, in his Home and Studio (1889, Oak Park, Illinois), Wright integrated work and family life under one roof, in a harmonious relationship with nature, and secluded from the city.[21] By organizing this, and future designs, around a central hearth, Wright created a “psychological center” that promoted values of community and the nuclear family.[22] The design reflected his Unitarian background and Transcendentalist beliefs, which “encouraged an honest life inspired by nature.”[23] Wright melded these beliefs with lessons from Silsbee and Sullivan,[24] whose influence can be seen in the home’s picturesque Shingle style, beloved by Silsbee, and its simplified and abstracted plan, promoted by Sullivan. The home’s façade employs geometric shapes, including a triangular front gable, polygonal bay windows, and circular veranda wall.[25] According to Wright, these features contrast with “candle-snuffer roofs, turnip domes [and] corkscrew spires” of the surrounding houses in Oak Park.[26] Wright’s Home and Studio foreshadows the principles of the American Arts and Crafts movement by combining Victorian beliefs and design practices, his mentors’ influence, and his own progressive innovation.

Tradition and Innovation (1894-1900)

While working for Adler & Sullivan, Wright accepted independent commissions for houses on the side. The firm forbade these sorts of “moonlighting” activities, however. Wright was fired from his position in 1893 when Sullivan discovered his “bootlegged” houses. From 1894 to 1900, Wright continued to experiment with different stylistic approaches, producing works that were at once progressive and conservative, innovative and traditional.[27] Generally speaking, Wright opposed historicizing design elements and incorporated them mainly to appease client tastes.[28] Even then, he did not merely reproduce historical styles – which included Dutch Colonial, Gothic, Tudor, and Shingle Styles – but instead aimed to simplify, rationalize, and “modernize” such styles.[29] Such an approach might be viewed as a sort of compromise.

For example, the Frederick Bagley House (1894, Hinsdale, Illinois) retains features of the popular Dutch Colonial, with its dormered gambrel roof, Ionic colonnaded veranda, and dark stained shingle siding.[30] At the same time, its innovations include a first floor plan organized around a central hearth, an octagonal library, and glass doors opening onto the veranda.[31]

Another example of Wright’s compromise between tradition and innovation are Robert Roloson’s four row houses (1894, Chicago, Illinois). On the one hand, Wright innovatively designed a series of courts and wells that would allow light and air ventilation between the buildings’ interior rooms. On the other hand, the row houses feature Gothicizing high-pitched gables, Sullivanesque spandrels, mullioned windows, and terrace balustrades.[32]

Wright’s Nathan G. Moore House (1895, Oak Park, Illinois) incorporates Tudor elements with its half-timbered upper stories and steeply pitched roofs, but its front porch deviates from convention.[33] According to Neil Levine, these examples might adopt historicizing elements in discrete and superficial ways but ultimately show Sullivan’s influence.[34] When Wright rejected the slavish copying of historical precedent, he actually “claimed a conservative stance, not a radical position,”[35] Richard Guy Wilson contends. Wright intended to return to the beginnings of architecture, not to ancient or Renaissance academics, but to nature and the regional vernacular.[36]

Works Cited

Alofsin, Anthony. Frank Lloyd Wright: The Lost Years, 1910-1922. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1993.

“Architectural Style Guide.” Historic New England. http://www.historicnewengland.org/preservation/your-older-or-historic-home/architectural-style-guide.

“Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio.” Frank Lloyd Wright Trust. http://www.flwright.org/researchexplore/homeandstudio.

“Fredrick Bagley House.” Frank Lloyd Wright Trust. http://flwright.org/researchexplore/wrightbuildings/frederickbagleyhouse.

Holzhueter, John O. “Wright’s Designs for Robert Lamp.” In Frank Lloyd Wright and Madison: Eight Decades of Artistic and Social Interaction, edited by Paul E. Sprague, 13-27. Madison, WI: Elvehjem Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1990.

Larkin, David, and Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer. Frank Lloyd Wright: The Masterworks. New York: Rizzoli, 1993.

Levine, Neil. The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996.

“Nathan Moore House.” Frank Lloyd Wright Trust. Accessed April 6, 2016. http://flwright.org/researchexplore/wrightbuildings/nathanmoorehouse.

Obniski, Monica. “The Arts and Crafts Movement in America.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolian Museum of Art. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/acam/hd_acam.htm.

Peck, Amelia. “American Revival Styles, 1840–1876.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolian Museum of Art. Accessed April 6, 2016. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/revi/hd_revi.htm.

“Robert Roloson Houses.” Frank Lloyd Wright Trust. http://flwright.org/researchexplore/wrightbuildings/robertrolosonhouses.

“The Arts and Crafts Movement.” Victoria and Albert Museum, London. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/t/the-arts-and-crafts-movement/.

Van Zanten, David. “Sullivan, Louis.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T082279.

Wilson, Richard Guy. “American Arts and Crafts Architecture: Radical though Dedicated to the Cause Conservative.” In “The Art That is Life”: The Arts and Crafts Movement in America, 1875-1920, edited by

Wendy Kaplan, 101-131. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1987.

“Wright and International Arts and Crafts.” Frank Lloyd Wright Trust. http://www.flwright.org/researchexplore/wrightandinternationalartsandcrafts.

Wright, Frank Lloyd. “In the Cause of Architecture (1908).” In Frank Lloyd Wright: Essential Texts, edited by Robert C. Twombly, 81-102. New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2009.

—-. “The Art and Craft of the Machine.” Brush and Pencil 8 (1901): 77-90.

Notes

- Neil Levine, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996), xiv. ↵

- Levine, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, xiv. ↵

- Levine, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, 3. ↵

- Levine, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, 8. ↵

- Levine, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, 8. ↵

- Levine, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, 8. ↵

- Richard Guy Wilson, “American Arts and Crafts Architecture: Radical though Dedicated to the Cause Conservative,” in “The Art That is Life”: The Arts and Crafts Movement in America, 1875-1920, ed. Wendy Kaplan (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1987), 106. ↵

- "The Arts and Crafts Movement," Victoria and Albert Museum, London, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/t/the-arts-and-crafts-movement/. ↵

- “Wright and International Arts and Crafts,” Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, accessed April 6, 2016, http://www.flwright.org/researchexplore/wrightandinternationalartsandcrafts. ↵

- Wilson, “American Arts and Crafts Architecture,” 101. ↵

- Wilson, “American Arts and Crafts Architecture,” 101. ↵

- Levine, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, 27. ↵

- Anthony Alofsin, Frank Lloyd Wright: The Lost Years, 1910-1922 (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 23. ↵

- Frank Lloyd Wright, “The Art and Craft of the Machine,” Brush and Pencil 8 (1901): 77-90. ↵

- Wright, “The Art and Craft of the Machine,” 78. ↵

- Wright, “The Art and Craft of the Machine,” and Wilson, “American Arts and Crafts Architecture,” 103. ↵

- Wright, “The Art and Craft of the Machine,” 80. ↵

- Wright, “The Art and Craft of the Machine,” 84. ↵

- Wright, “The Art and Craft of the Machine,” 87. ↵

- Alofsin, Frank Lloyd Wright: The Lost Years, 1910-1922, 22. ↵

- Levine, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, 25. ↵

- Alofsin, Frank Lloyd Wright: The Lost Years, 1910-1922, 25. ↵

- “Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio,” Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, accessed April 6, 2016, http://www.flwright.org/researchexplore/homeandstudio. ↵

- “Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio,” http://www.flwright.org/researchexplore/homeandstudio. ↵

- “Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio,” http://www.flwright.org/researchexplore/homeandstudio. ↵

- “Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio,” http://www.flwright.org/researchexplore/homeandstudio. ↵

- Levine, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, 27. ↵

- “Fredrick Bagley House,” Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, accessed April 6, 2016, http://flwright.org/researchexplore/wrightbuildings/frederickbagleyhouse. ↵

- Levine, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, 28. ↵

- Levine, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, 27, and “Fredrick Bagley House,” Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, http://flwright.org/researchexplore/wrightbuildings/frederickbagleyhouse. ↵

- “Fredrick Bagley House,” http://flwright.org/researchexplore/wrightbuildings/frederickbagleyhouse. ↵

- Levine, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, 27, and “Robert Roloson Houses,” Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, accessed April 6, 2016, http://flwright.org/researchexplore/wrightbuildings/robertrolosonhouses. ↵

- Levine, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, 27, and “Nathan Moore House,” Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, accessed April 6, 2016, http://flwright.org/researchexplore/wrightbuildings/nathanmoorehouse. ↵

- Levine, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, 28. ↵

- Wilson, “American Arts and Crafts Architecture,” 102. ↵

- Wilson, “American Arts and Crafts Architecture,” 102. ↵