The Myth of Isolationism

Civil Society as Empire

In tandem with the export of American goods and services was the export of American institutions. Indeed, some scholars argue that underlying the consumer culture’s acceptance by many Europeans was the acceptance of American notions of Civil Society and American institutions of Civil Society. In this view Rotary Clubs were the advance guard of the American Market Empire, conditioning Europeans, particularly European elites to what De Grazia calls the “material commonality of daily needs.”

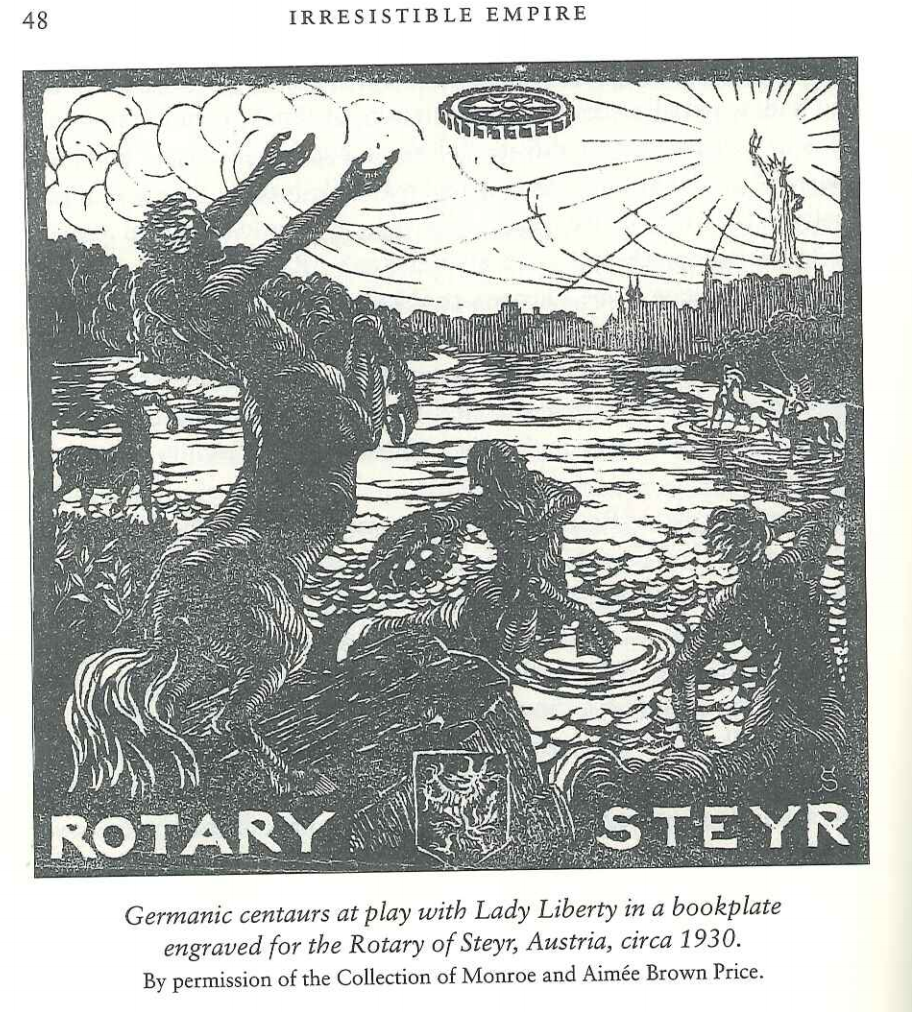

Born in Minneapolis, MN, Rotary Clubs were a distinctly middle-class, businessmen invention. Such clubs became the vehicle by which many businessmen engaged in the civic life of their community. Organizing events, supporting charities and most of all engendering a sense of ideals and community among its members, Rotary spread like wildfire throughout the US. In the wake of WW I, when Europeans were casting about for new ideologies after what seemed an apocalyptic war, American civil institutions and ideals like the Rotary had appeal. Epitomizing the phenomena was the German writer and Nobel Laureate Thomas Mann. Mann represented the height of European culture in his day, the essence of what it meant to be civilized. Yet it was Mann, and people like him, who embraced American conceptions of civil society and joined groups like Rotary. By the mid-1930s Rotary had over 300 branches in Europe.

Rotary is just one example of the export of US civil society — voluntary associations, social scientific knowledge, and civic spirit. Far from disengaging with the rest of the world, US citizens actively, and successfully, sought to engage with and export to the rest of the world. As Rotary shows, this was not a simple, crass desire for money and profit, this was an export of a new American consumer society in toto.