15 Putting It All Together

The problem is not that there are problems. The problem is expecting otherwise and thinking that having problems is a problem.

—Theodore Rubin,

American psychiatrist and author

Objectives

After reading this lesson, you will be able to

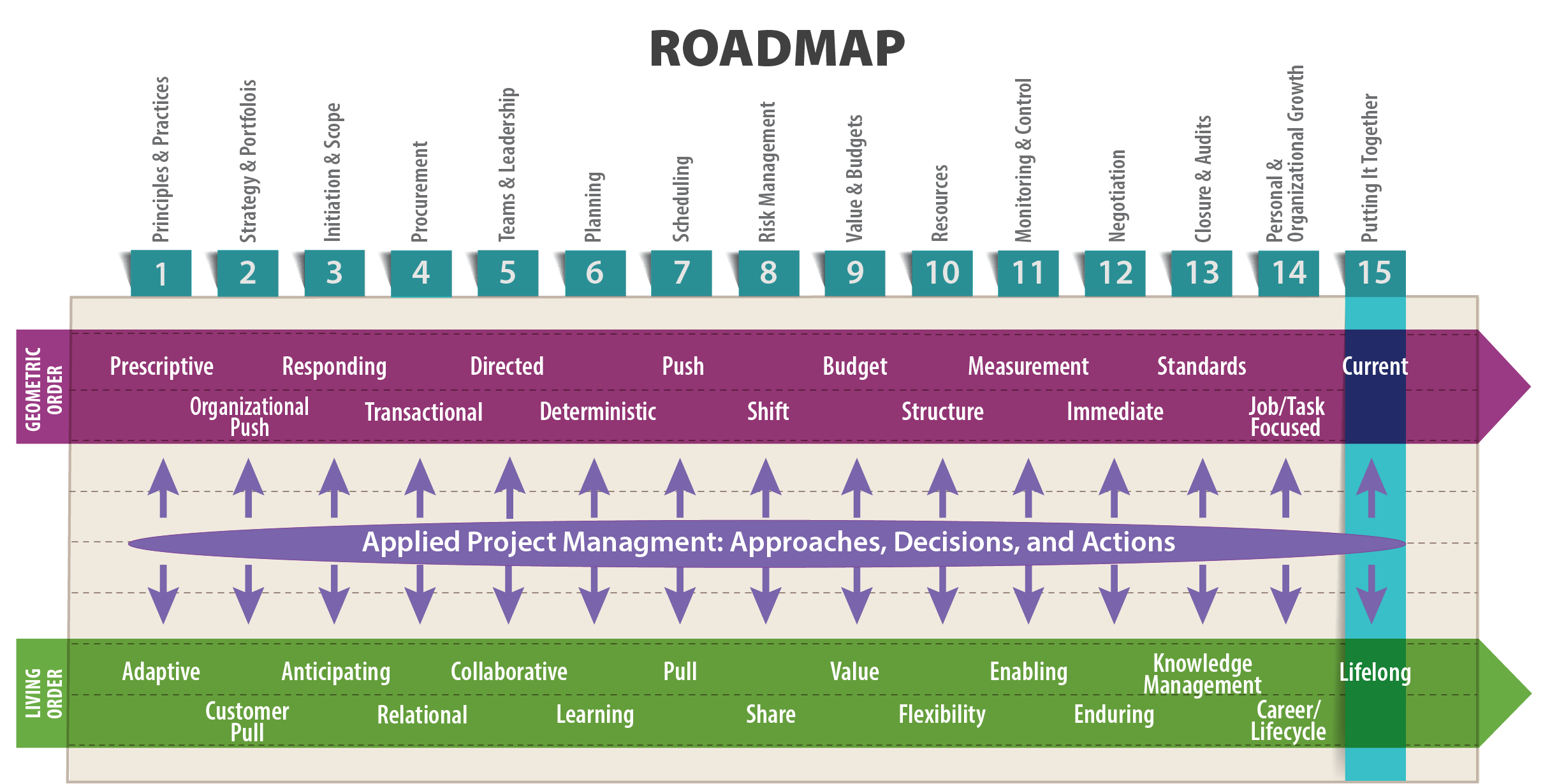

- List some new practices for project management based on the first fourteen lessons in this book

- Discuss James March’s ideas on thinking like a poet to become a better project manager

- Explain the difference between event-driven and intention-driven project management

- Get started creating your own professional development plan

The Big Ideas In this Lesson

- As you look to the future, keep in mind that a living order approach to personal development focuses on lifelong learning, rather than understanding only what you need to know to master the current situation.

- A poet’s ability to interpret events, and to tell other people what they mean, is extremely useful in living order, where unexpected events unfold every day, unforeseen by even the most carefully constructed project plan.

- After formulating an interpretation of events, project managers must come up with a solution, circling back to revise their interpretation of the situation as necessary.

- The event-driven nature of project management, which can pull your attention in a dozen different directions at once, can leave little time and energy for planning and acting on your long-term career goals. It’s essential to take time to plan your professional development.

15.1 Reassess and Plan for the Future

This last lesson is an opportunity for you to look back at your understanding of project management at the beginning of this book; assess how your abilities align with your new, expanded conception of project management; and develop a plan for incorporating these new ideas and practices into your work. In other words, this is an opportunity to plan for change. A short list of new practices for readers of this book might include

- Recognize when a geometric order approach is useful in a project, and when a more flexible, living order approach is best

- Look for opportunities to incorporate Lean or Agile principles into your projects

- Make decisions about new projects in relation to your organization’s overall project portfolio

- Identify what makes a particular project successful, with a focus on the customer’s definition of value, and communicate that to all stakeholders.

- Limit the amount of detail in a project plan and schedule to the amount required to effectively guide the project team

- Be prepared to adapt and improvise in fast-changing situations, rather than attempting to stick to a plan that is no longer relevant

- Employ monitoring and control strategies that provide the right amount of information, targeted to the people who need that information to make on-going decisions about the project

- Regularly conduct project-review and project-closure activities, so as to keep current projects on track and retain vital information for future projects

- Take advantage of learning opportunities wherever they arise throughout your career

As you have read throughout this book, these are all important and effective ways of keeping projects on-track and headed toward success in the unpredictable, living-order conditions of the modern world. Hopefully, you have already begun changing your approach to project management to incorporate some or all of these practices. You might also hope to lead your entire organization toward some essential changes as well. So, let’s take some time to think about the nature of change and the mind-expanding possibilities of new ideas. It all starts with seeing the world differently.

15.2 Technical Project Manager as Plumber and Poet

In his novel 1984, George Orwell describes a dystopian state in which human thought is controlled by Newspeak, the state’s official language, which citizens are forced to adopt. Because Newspeak lacks words like “freedom” and “justice,” thoughts about such things gradually become “literally unthinkable, at least so far as thought is dependent on words…. Newspeak was designed not to extend but to diminish the range of thought, and this purpose was indirectly assisted by cutting the choice of words down to a minimum” (Orwell). By restricting the ability of citizens to think thoughts that might upset the current state of affairs, the government is able to prevent revolution from taking root.

In his novel, Orwell is making points about the nature of repressive political states. But he’s also commenting on the power of any organization to restrict the way its members think by controlling the official terminology and sanctioned procedures for getting things done. In any large organization, giving an honest assessment of any situation can be exceedingly difficult, especially when the organization itself wants you to see things differently. In an interview with the Harvard Business Review, James March, one of the seminal scholars and thinkers on organizational theory, describes the predicament of astute modern managers, who perceive uncertainty all around, but are compelled by the pressures of organizational thinking to blind themselves to that reality:

The rhetoric of management requires managers to pretend that things are clear, that everything is straightforward. Often, they know that managerial life is more ambiguous and contradictory than that, but they can’t say it. They see their role as relieving people of ambiguities and uncertainties. They need some way of speaking the rhetoric of managerial clarity while recognizing the reality of managerial confusion and ambivalence. (Coutu 2006)

In a collection of his lectures, James March explains that to avoid this kind of self-imposed blindness, managers need to combine their natural plumber’s tendency—the tendency to zero in on problems and fix them—with the poet’s bold, creative approach to the world:

There are two essential dimensions of leadership: “plumbing,” i.e., the capacity to apply known techniques effectively, and “poetry,” which draws on a leader’s great actions and identity and pushes him or her to explore unexpected avenues, discover interesting meanings, and approach life with enthusiasm.

The plumbing of leadership involves keeping watch over an organization’s efficiency in everyday tasks, such as making sure the toilets work and that there is somebody to answer the telephone. This requires competence, not only at the top but also throughout all the parts of the organization; a capacity to master the context (which supposes that the individuals demonstrating their competence are thoroughly familiar with the ins and outs of the organization); a capacity to take initiatives based on delegation and follow-up; a sense of community shared by all members of the organization, who feel they are “all in the same boat” and trust and help each other; and, finally, an unobtrusive method for coordination, with each person understanding his or her role sufficiently well to be able to integrate into the overall process and make constant adjustments to it….

Leadership also requires, however, the gifts of a poet, in order to find meaning in action and render life attractive. The formulation and dissemination of interesting interpretations of reality form the basis for constructive collective action…. Words allow us to forge visions, and poetic language, through its evocative power, allows us to say more than we know, to teach more than we understand. (March and Weil 2005)

Thinking like a poet opens the door to the kind of personal change that will make you a better project manager. At the same time, thinking like a poet will give you the ability to inspire change in your organization. As you’ll see in the next section, a poet’s ability to interpret events, and to tell other people what they mean, is extremely useful in living order, where unexpected events unfold every day, unforeseen by even the most carefully constructed project plan.

You Already Think Like a Poet

James March has suggested that managers could benefit from reading poetry, which forces readers to marshal their powers of interpretation, looking for multiple layers of meaning in any one word (Coutu 2006). But whether or not you are interested in reading poetry, you should at least be aware that living order is ultimately a poetic idea, developed by the French philosopher Henri Bergson. When he first used the term, in his book Creative Evolution, Bergson was talking about the artistic process, which appears chaotic from the outside, but can produce works of extraordinary order and complexity (1911). Living order is a complicated idea, and at first blush it doesn’t even make sense. How can order be alive? What does that mean? Hopefully, after fourteen lessons, you do have a sense of what it means. You probably even feel comfortable using the term “living order” to identify certain phenomena in your professional life. That is, you reinterpreted two English words—“living” and “order”—and, as a result, internalized a new understanding of the world. In other words, you have begun thinking like a poet.

15.3 Event-Driven and Intention-Driven Project Management

As an engineer, you are probably inclined toward the plumbing tasks associated with leadership. After all, almost by definition, engineers like to fix things. And you might think that the poet part of the equation is something entirely new to you. But the work of Swedish researchers Ingalill Holmberg and Mats Tyrstrup suggests that employing a poet’s interpretive skills—that is, looking at a situation and telling other people what it means—is something good managers do every day. You probably have more experience at it than you think.

Holmberg and Tyrstrup developed their theory when studying everyday leadership—that is, the decisions and activities that take up the vast majority of a manager’s time. In interviews with managers at TECO, the Swedish international telecom company, they found that only 10% of projects were completed in the traditional, geometric way, with events unfolding according to plan. Another 20% are driven by a manager who saw himself or herself as heroic for solving unexpected problems and forcing the project to unfold as originally planned. The researchers noted that managers especially loved to describe a project as “a story of heroic feats.” They explain that

many managers tend to describe their efforts according to this model. They begin with a challenging problem (which, by the way, is much bigger than initially expected). A process follows that includes many difficult turns. Knotty problems arise, and at times everything looks bleak—very bleak indeed. But the competent manager has a basic agenda consisting of a number of stages to follow and steps to take. In hindsight, it can be claimed that the whole process has gone according to plan and a successful conclusion has been reached. (54)

Managers who describe their successes in this way tend to think leadership is largely a matter of knowing “today what should be done tomorrow in order to reach the desired results” (54). In other words, they see projects as intention-driven. They believe that a heroic manager with clearly defined intentions can make anything happen.

But according to Holmberg and Tyrstrup, managers who view themselves in this heroic light are deceiving themselves, because the vast majority of a manager’s time is spent on problems that nobody did or could expect. The researchers call these “Well then—what now?” situations. They argue that almost all of a manager’s time is spent trying to answer that question—and not because things were poorly planned at the outset, but because that’s just how things work in a complicated organizational setting. As much as heroically-inclined managers would like to believe that their own intentions are the most powerful force in any project, in reality projects are nearly always event-driven, with managers forced to respond to changing situations from day to day. “Either something unexpected happens, or what was expected to happen does not” (58).

Using a Time Management Quadrant

As you turn your attention from one “Well then—what now?” situation to another, it’s easy to lose track of priorities. In particular, you might fail to leave time for the large-scale, sense-making thinking required to keep a project on track over the long term. In The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, Stephen Covey recommends using a time management quadrant, like the one shown in Figure 15-1. Make a diagram like this, and then keep track of how you spend your time, writing each activity into the appropriate quadrant (Covey 1989).

People tend to spend most of their time on Quadrants I and III, neglecting Quadrant II. Thus, long term planning and sense-making (which are not urgent but very important) tend to fall by the wayside. For some suggestions on how to use a time management quadrant to eliminate pointless, Quadrant IV tasks from your work life in order to focus more on the essential Quadrant II tasks, see this helpful article: https://www.usgs.gov/media/files/time-management-grid.

Holmberg and Tyrstrup describe a “Well then—what now?” project as follows:

You find yourself in a problematic situation, working hard and wrestling with the issues as they appear, only to find you are constantly trying to grasp the situation. It is not at all certain how you got where you are or what the situation means. It is extremely difficult to assess how the situation fits with the intentions articulated a few days, a week, or a month ago. It is hard to tell what has been completed, what is still going on, or what is yet to be accomplished. People are constantly at your throat, asking for different instructions or directions. People higher up in the hierarchy, those lower down, and even those at the same level want information and reports that give the results of decisions taken and activities performed. One event seems to give rise to another according to a logic that is anything but obvious. As a manager, you are tired and need a break to go through your papers, emails, the heaps of files, and the phone messages in order to sort out your thoughts and feelings. (55)

In a situation like this, the manager’s main job is to interpret what’s going on—that is, make sense of the situation:

In each case, the manager had to interpret what had already happened in order to formulate what the next step should be. What was the significance of what had or hadn’t happened? How might these events and non-events be best explained, and what are their implications? (59)

After formulating an interpretation, managers must come up with a solution, circling back to revise their interpretation of the situation as necessary.

This brings us back to March’s idea that a leader is partly a plumber and partly a poet. A “Well then—what now?” problem can only be solved by a manager with a poet’s ability to interpret the situation, to see into the heart of the matter and explain to everyone else what’s going on. Then, acting like a plumber, the manager needs to figure out a way to solve the problem. Often, solving the problem also requires quite a bit of poetic creativity and vision.

Holmberg and Tyrstrup conclude their study with some practical suggestions designed to nudge large organizations away from the assumption that unexpected events can be prevented by more detailed planning, which can be extremely time-consuming and costly. Instead, they argue, organizations should focus on hiring managers who can deal with the unexpected. Their research implies that organizations should focus on “selecting managers who are prepared to give up unilateral control and instead to rely on the creativity inspired by improvised actions” (65). Likewise, management training, they argue, should focus on helping managers come up with creative solutions to the question “Well then—what now?”

As you look to your future as a technical project manager, be alert to your own tendency to see yourself as a hero in the midst of chaos. Instead, remember that resolving “Well then—what now?” situations is the main job of a project manager. You need to be able to deal with them creatively and with as little drama as possible.

Becoming an Expert Technical Project Manager: the 10,000 Hour Rule, Revised

You might have heard people talk about the 10,000 hours rule. As popularized by Malcolm Gladwell in his book Outliers, the rule holds that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to become an expert at anything, including project management. But according to Anders Ericsson, the psychologist whose research inspired the maxim, simply doing something over and over won’t lead to true expertise. Instead, you need to actively correct your performance to achieve real excellence. Maria Popova summarizes his findings:

The secret to continued improvement, it turns out, isn’t the amount of time invested but the quality of that time. It sounds simple and obvious enough, and yet so much of both our formal education and the informal ways in which we go about pursuing success in skill-based fields is built around the premise of sheer time investment. Instead, the factor Ericsson and other psychologists have identified as the main predictor of success is deliberate practice—persistent training to which you give your full concentration rather than just your time, often guided by a skilled expert, coach, or mentor. (n.d.)

So, to become an expert technical project manager, you need to invest time in constant learning and training. But you need to do this with an active attention toward self-improvement. To avoid “ceasing to grow and stalling at proficiency level … you need to continually shift away from autopilot and back into active, corrective attention” (Popova).

You can read Popova’s excellent summary of the latest research on the 10,000 hours rule here: https://www.brainpickings.org/2014/01/22/daniel-goleman-focus-10000-hours-myth/. And while you’re at it, consider subscribing to her email newsletter, which explores a huge variety of topics related to culture, history, and art. It’s a wonderful way to learn about issues that lie beyond the boundaries of the engineering world, making it an excellent professional development resource. Reading regularly will ensure that you’re familiar with all the big topics currently circulating in the culture. You can subscribe here: https://www.brainpickings.org/newsletter/

15.4 Creating a Professional Development Plan

In this book, you’ve learned about the importance of planning to ensure a technical project’s success. The same is true of your career. Unfortunately, the event-driven nature of project management, which can pull your attention in a dozen different directions at once, can leave little time and energy for planning and acting on your long-term career goals. As a result, some project managers end up moving from one job to another with no real plan in mind. In other words, they fall into the trap of tolerating an event-driven series of positions at various organizations, rather than insisting on an intention-driven, goal-oriented career. The first step in taking control of your career is creating a professional development plan (PDP), which is a document that describes

- Your current standing in your field, including a brutally honest assessment of your strengths and weaknesses. Use the Project Management Self-Assessment form provided in Figure 15-2 to begin holding yourself to account.

- Your short- and long-term career goals. Creating a list of goals typically involves a fair amount of research, so that you can be sure you fully understand the options available to you.

- A plan for achieving your goals that includes specific deadlines. Again, this part of your professional development plan will require some research, so that you fully understand the best possible ways to achieve your goals. For example, you might want to investigate useful certifications or professional conferences.

Figure 15-2: Project Management Self-Assessment

Download Figure 15-2 in PDF form

To create a meaningful development plan, you also need to engage a trusted mentor and perhaps a few valued colleagues. Connect with people who are willing to share experiences with you, who understand the big picture, and who can give you honest assessments of your strengths and weaknesses. Definitely take advantage of any formal mentorship programs available through your organization or in your field. However, according to Terry Little in Becoming a Project Manager, you are likely to get the best results through more informal mentoring arrangements with willing senior employees. It’s possible a senior manager who takes mentoring seriously will approach you about establishing a mentor/mentee relationship, but if that doesn’t happen, don’t be afraid to seek out your own mentors. But what makes a good mentoring relationship? According to Little, the following principles are a good foundation:

- Mentors must be willing to spend time doing it.

- Mentees must be willing to learn.

- Mentoring is everyone’s responsibility, not just the responsibility of those in senior positions.

- Advice to mentees should be predictable and personal.

- With any position you hold, your behavior should be worthy of emulation. (2018)

No matter how much work you and your mentor put into your professional development plan, the plan is only useful if you actually monitor your progress in achieving your goals and take the time to update the plan throughout your career. Whereas projects are team efforts involving collaboration among many parties, your professional development is entirely your responsibility. In an article for Forbes, Chrissy Scivicque emphasizes that while your organization’s human resources department might help you create a plan, executing it successfully is really up to you:

Your professional development is not the responsibility of anyone but you. Not your company, not your boss, not even your coach. Just you.

Some companies try to help with the process by helping employees create professional development plans (PDP) as part of the performance review process. While it’s a nice gesture, it simply isn’t very useful for the vast majority of employees.

In my experience, I’ve found that a PDP created at the behest of an employer is often an exercise for management, not the employee. In fact, if the employee will later be judged on that criteria, he or she actually feels encouraged to aim low so as not to be set up for future failure. For those who happen to have bigger goals that don’t involve working for the company, the PDP is pretty meaningless. The employee ends up playing a game, telling the manager what he wants to hear and not using the plan to facilitate real, desired professional growth.

Even if your company helps you develop a plan, it’s always a smart idea to create one of your own in private. This will help you identify and take action on growing the skills needed to achieve your true long-term career goals, whether or not they involve your current company. (2011)

In her article, Scivicque also emphasizes that a professional development plan is only useful if you revise it regularly to reflect new opportunities and challenges, as well as your own changing aspirations. You can read her complete article here: http://www.forbes.com/sites/work-in-progress/2011/06/21/creating-your-professional-development-plan-3-surprising-truths/#5cd14a4627bb.

Experience, Reflection, and Mentoring

In their book Becoming a Project Leader, Alexander Laufer, Terry Little, Jeffrey Russell, and Bruce Maas provide real-life case studies of people struggling with and growing into the role of project manager. They explain that “the large sample of project managers we studied did not become successful due to intensive and formal classroom education. Rather, the primary means for their development was on-the-job learning” (109). According to their research, the three most important avenues for this vital form of learning are pursuing challenging tasks to gain experience, working with a mentor, and learning through communities of practice. “Project managers develop as successful leaders by employing a variety of practices which are from bottom to top (the project manager tackling challenging tasks and affecting the organization), top to bottom (mentoring), and across the organization (community of practice)…. If an organization is to grow and weather the inevitable ups and downs it will face in a dynamic environment, professional development is essential” (127).

One of the great benefits of taking part in a community of practice is that it offers a low-pressure setting in which people can talk about their work, usually in the form of stories. The ability of stories to transfer knowledge and wisdom among people cannot be overemphasized. “People love to read stories because they attract and captivate, can convey a rich message in a non-threatening manner, and are memorable. Stories are thus the most effective learning tool at our disposal, especially in situations where the prospective learner suffers from a lack of time—which is the case for most project managers” (Laufer et al. 2018, 121-122).

All of these professional development tactics draw on the 70/20/10 model for learning and development, which holds that 70% of learning comes from challenging assignments, 20% comes from relationships with coworkers including mentors and communities of practice, and 10% from formal training. You can learn more about the 70/20/10 model here: https://trainingindustry.com/wiki/content-development/the-702010-model-for-learning-and-development/.

15.5 The Future of Technical Project Management

One important part of planning for your professional development is keeping an eye on trends that will shape technical project management in the coming years. Technological advances, expanding globalization, and new communication and data systems will all change how technical project managers do their jobs. Here’s a summary of emerging trends, along with links for more information:

- Data analytics: Businesses are increasingly collecting mountains of data on quality assurance testing, customer behaviors and preferences, in-field equipment performance, warranty claims, and so on. These data can drive the justification for projects, help to focus project efforts, and inform project progress. Project managers will need to cultivate their ability to extract meaningful information from otherwise overwhelming stores of data, and then use that information to make crucial decisions and to shape day-to-day project management. These articles explain how to use data analytics to improve project outcomes:

- Business Agile: The Agile development model has leapt over the borders of IT projects into the larger world. Companies are now incorporating Agile principles into “the whole of a company’s function,” with massive implications for how business decisions are made and plans are executed (Burger, Business Agile and the Future of Project Management 2017). Among other innovations, this new approach to business emphasizes continuous learning, information-sharing among departments, and incentives that “support measuring outcomes, making evidence-based decisions, and learning” (Gothelf 2014). Read this blog post for an in-depth look at the implications of business Agile: https://blog.capterra.com/business-agile-and-the-future-of-project-management/. This article from the Harvard Business Review makes the case for weaving Agile-thinking into everything a company does: https://hbr.org/2014/11/bring-agile-to-the-whole-organization. The website for the Agile Business Consortium is an excellent source of resources on the topic: https://www.agilebusiness.org/business-agility.

- Diversity initiatives: According to Rachel Burger, the world of project management has been slow to make hiring a diverse group of employees a priority, even while other fields have been making major strides in this area. But a trend toward diversity “is trickling in from the business community and the political climate as a whole.” As a result, project managers can expect to hear more about the need for diverse teams—that is, teams that include an equal number of men and women, with representation from as many races, cultures, sexual orientations and religions as possible, and built-in measures for accommodating disabilities. But these changes will not occur in a vacuum. You should expect lots of arguments about the best way to proceed. Burger advises project managers to “take advantage of new community offerings about diversity and inclusiveness, and get ready for industry-level conflicts about people management in regards to ability, age, ethnicity, gender, race, religion, sexual orientation, and class” (2017). You’ve read about the benefits of having a diverse team in Lesson 5. This article summarizes these benefits: https://www.liquidplanner.com/blog/the-new-secret-to-successful-teams-diversity/. This article from PMI explains how to overcome misunderstandings that can arise on multicultural teams: https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/dealing-cultural-diversity-project-management-129.

- The internet of things and artificial intelligence: Advances in technology will affect every business in the world, one way or another (Burger 2017). This is definitely true of the internet of things (IoT), which is the “system of interrelated computing devices, mechanical and digital machines, objects, animals or people that are provided with unique identifiers (UIDs) and the ability to transfer data over a network without requiring human-to-human or human-to-computer interaction” (TechTarget n.d.). This article by Anna Johansson describes the many ways IoT has and will continue to change modern business: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/anna-johansson/8-ways-the-internet-of-th_b_11763836.html. You probably already have experience with forms of artificial intelligence (AI) such as Amazon’s Alexa, or the Apple’s Siri. But these automated personal assistants are just the tip of the iceberg. This article describes ways that AI will change business and how leaders will need to adapt: https://hbr.org/2020/03/ai-is-changing-work-and-leaders-need-to-adapt.

- Globalization: The Levin institute at the State University of New York (SUNY) defines globalization as “a process of interaction and integration among the people, companies, and governments of different nations, a process driven by international trade and investment and aided by information technology. This process has effects on the environment, on culture, on political systems, on economic development and prosperity, and on human physical well-being in societies around the world” (The Levin Institute n.d.). Globalization has already had a profound effect on the way the world does and will continue to do business in myriad ways. In a NASA roundtable discussion, Greg Balestrero discussed the effects of globalization on the supply chain: “It’s very difficult to think of any company or organization that doesn’t feel the pressures and the implications of globalization on the supply chain. And it’s an intellectual supply chain as well as a physical supply chain. The global supply chain is a growing issue…. With globalization comes a challenge of having a common framework and understanding—as simple as a lexicon, as complicated as a common process—for project and program management” (APPEL News Staff 2007). You can learn more about this essential topic at www.globalization101.org, a website maintained by the Levin Institute.

Other issues that will continue to have a huge effect on technical project management in the coming years include

- Lean and Agile: According to expert John Shook, despite almost two decades of effort, the construction industry is only in the early stages of effectively implementing Lean principles in all phases of construction (Wiegand 2016). Likewise, IT professionals still face many challenges in their quest to take advantage of Agile principles and practices in an organizationally appropriate and effective manner.

- Emerging technology: An article in Engineering News-Record describes the use of hologram headsets that allow a worker to see a 3D model of what she needs to build directly on site, making it possible to begin assembling part of a building without even referring to a tape measurer (Rubenstone 2016). This is just one example of the fast-moving technological changes that will affect your work as a technical project manager in the near future.

- Partnerships: As the tendency toward globally interconnected businesses intensifies, formal international business partnerships will become the norm rather than the exception. To successfully manage projects that span multiple countries, you’ll need to focus on your cross-cultural competencies, making sure you are prepared to interact with people from all over the world.

~Practical Tips

This set of practical tips summarizes the advice you’ve read in earlier lessons. To help promote an understanding of the role of geometric and living order in your organization’s projects, consider printing this list and posting it somewhere where your colleagues and project stakeholders can easily read it. And be ready to discuss these ideas with anyone who asks about them.

- Throughout a project, recognize the tension that exists between geometric and living order, and avoid imposing a geometric process on a situation that requires a more flexible, living order approach.

- Put as much effort as you possibly can into starting a project well because the way you start a project has a big impact on how you finish.

- In all stages of a project, take time to remind stakeholders how the customer perceives the project’s value. Make sure everyone involved can clearly articulate the customer’s definition of the project’s value.

- Continually work toward building a functional, collaborative team. Don’t waste time trying to achieve the impossibility of a perfect team.

- Do all you can to make sure all project stakeholders understand the definition of project success.

- Use the planning part of any project as an opportunity for thinking and collaboration. Focus less on the plan itself and more on starting the dialogue with all stakeholders.

- Do not let a project evolve without continually referring to and connecting back to your organization’s overall strategy. At every stage of planning and executing a project, incorporate strategic thinking.

- In all procurement-related tasks, focus on best value rather than least initial cost.

- Use the scheduling part of any project as an opportunity to think about project tasks at varying levels of detail, and as an opportunity to communicate with stakeholders about the best way to achieve project success.

- Don’t shy away from confronting the uncertainty in any project. Only by understanding the many forms of uncertainty associated with a project can you understand the degree of risk involved.

- Accept the fact that resources are usually scarce and constrained, and use your project management skills to use those scarce and constrained resources effectively.

- In a dynamic, changeable environment, move beyond the traditional view of monitoring and control, which emphasizes gathering data about the past, and instead adopt a pull approach to monitoring and control, which emphasizes data about the current time and the immediate future.

Finally, here are some concluding practical tips on management and leadership, adapted from the work of Alexander Laufer, whose book Mastering the Leadership Role in Project Management (2012) has provided a wealth of inspiration for these lessons.

- Always keep the context in mind: Principles and practices must be modified to fit the context of a project situation.

- Adapt when necessary, instead of attempting to control everything: Projects are plagued with questions and problems. A successful manager has the flexibility to adapt as necessary to address these matters and not simply strive to control them.

- Be prepared to manage and lead: In some ways, a technical project requires the same combination of management and leadership as driving a car. You need to remain aware of everything going on with the controls on the dashboard (management) while at the same time looking out the windshield to make sure you reach your destination (leadership).

- Be prepared for a shift from living order to geometric order, once things get going: Many projects start in living order (and a high degree of uncertainty) and transition to geometric order.

- Don’t forget the beauty of AND: Project management often involves combining two different activities or ways of thinking about a project, such as leadership AND management, stability AND flexibility, processes AND practices, thinking AND doing.

- Look for ways to collaborate at all times: The primary role of a project manager is to build collaboration, interdependence, and trust among the project stakeholders.

- Think of yourself as a problem solver: Successful project managers develop expertise in problem identification and solving.

- Remember, everything you do or learn adds to your wealth of knowledge and experience: Seek out new ways to add to your practical experience and overall knowledge. Job assignments are one obvious way to do this, but don’t forget other options, such as mentoring relationships, and stories told by your colleagues about past projects.

~Summary

- New project management practices for readers of this book include recognizing when a geometric order approach is best and when a living order approach is best, being prepared to adapt and improvise, and limiting the amount of detail in a project plan and schedule to the amount required to effectively guide the project team.

- According to James March, an effective leader knows how to work like a plumber, by “keeping watch over an organization’s efficiency in everyday tasks,” and also like a poet, who strives to “explore unexpected avenues, discover interesting meanings, and approach life with enthusiasm” (March and Weil 2005).

- Many managers think leadership is largely a matter of knowing “today what should be done tomorrow in order to reach the desired results” (Holmberg and Tyrstrup 2012, 54). In other words, they see projects as intention-driven. But according to Swedish researchers Ingalill Holmberg and Mats Tyrstrup, managers who view themselves in this heroic light are deceiving themselves, because the vast majority of a manager’s time is spent on problems that nobody did or could expect. In other words, projects are nearly always event-driven, with managers forced to respond to changing situations from day to day (58).

- The first step in taking control of your career is creating a professional development plan (PDP), which is a document that describes your current standing in your field, your short- and long-term career goals, and a plan for achieving your goals, including specific deadlines.

~Glossary

- event-driven—Term used to describe a project that unfolds in response to changing events.

- intention-driven—Term used to describe a project that unfolds according to the single-minded intention of the project manager.

- Internet of things (IoT) —The “system of interrelated computing devices, mechanical and digital machines, objects, animals or people that are provided with unique identifiers (UIDs) and the ability to transfer data over a network without requiring human-to-human or human-to-computer interaction” (TechTarget n.d.).

- professional development plan (PDP)—A document that describes 1) your current standing in your field, including a brutally honest assessment of your strengths and weaknesses; 2) your short- and long-term career goals; and 3) a plan for achieving your goals that includes specific deadlines.

~References

APPEL News Staff. 2007. “What’s Ahead for Project Management: A Roundtable Discussion with PMI.” ASK OCE 2 (2). https://appel.nasa.gov/2010/02/27/ao_2-2_f_ahead-html/.

Bergson, Henri. 1911. “Creative Evolution.” Project Gutenberg. Accessed June 15, 2018. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/26163/26163-h/26163-h.htm.

Burger, Rachel. 2017. “Business Agile and the Future of Project Management.” Capterra Project Management Blog. August 14. https://blog.capterra.com/business-agile-and-the-future-of-project-management/.

—. 2017. “The 5 Biggest Project Management Trends Shaping 2018.” Capterra Project Management Blog. November 14. https://blog.capterra.com/the-5-biggest-project-management-trends-shaping-2018/.

Coutu, Diane. 2006. “Ideas as Art [an interview with James March].” Harvard Business Review, October. https://hbr.org/2006/10/ideas-as-art.

Covey, Stephen R. 1989. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. New York: Free Press.

Gothelf, Jeff. 2014. “Bring Agile to the Whole Organization.” Harvard Business Review, November 14. https://hbr.org/2014/11/bring-agile-to-the-whole-organization.

Holmberg, Ingalill, and Mats Tyrstrup. 2012. “Chapter 3: Managerial Leadership as Event-Driven Imrovisation.” In The Work of Managers: Towards a Theory of Management, by Stefan Tengblad, 47-68. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Laufer, Alexander. 2012. Mastering the Leadership Role in Project Management: Practices that Deliver Remarkable Results. Upper Saddle River: FT Press.

Laufer, Alexander, Terry Little, Jeffrey Russell, and Bruce Maas. 2018. Becoming a Project Leader: Blending Planning, Agility, Resilience, and Collaboration to Deliver Successful Projects. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

March, James G., and Thierry Weil. 2005. On Leadership. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Orwell, George. 1949. “1984: Appendix, The Principles of Newspeak.” George Orwell. Accessed December 11, 2016. http://orwell.ru/library/novels/1984/english/en_app.

Popova, Maria. n.d. “Debunking the Myth of the 10,000-Hours Rule: What it actually Takes to Reach Genius-Level Excellence.” BrainPickings. Accessed December 22, 2016. https://www.brainpickings.org/2014/01/22/daniel-goleman-focus-10000-hours-myth/.

Rubenstone, Jeff. 2016. “Mixing Reality on Site: Hologram Headsets Put 3D Models Front and Center.” Engineering News-Record, November 28/December 5: 20-24.

Scivicque, Chrissy. 2011. “Creating Your Professional Development Plan: 3 Surprising Truths.” Forbes, July 21. http://www.forbes.com/sites/work-in-progress/2011/06/21/creating-your-professional-development-plan-3-surprising-truths/#5cd14a4627bb.

TechTarget. n.d. “internet of things (IoT).” TechTarget. Accessed 17 2018, July. https://internetofthingsagenda.techtarget.com/definition/Internet-of-Things-IoT.

The Levin Institute. n.d. “What Is Globalization?” Globalization 101. Accessed July 17, 2018. http://www.globalization101.org/what-is-globalization/.

Wiegand, John. 2016. “Viewpoint: Construction Project Delivery, Dispelling Lean Myths.” Engineering News-Record, November 15.