3 September 21 – Nation Building in North Korea

Nation Building in North Korea: The Bountiful Years Under Kim Il Sung, 1950s-1970s

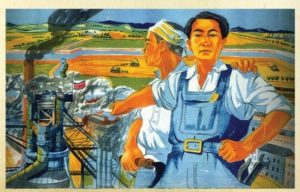

Worker and peasant, the builders of a modern, industrialized, and prosperous North Korea. (North Korean illustration, year unknown).

- Charles ARMSTRONG, The Koreas, 57-75

- When We Pick Apples (dir. KIM Yong-ho, 1971)

- KIM Il Sung, “Let Us Consolidate and Develop the Great Results of the Pukchong Meeting,” 111-124

Note: Homework 2 is based on the above readings and film and is due Monday at midnight.

This week, we explore decolonization in North Korea and in South Korea. (Please see below for more on decolonization.) North Korea and South Korea were rival states that were diametrically opposed to each other. One was communist and carried forth a social revolution (1945-1948) that fundamentally overturned the social structure; the other was anticommunist and (ostensibly) liberal capitalist, and sought to preserve elements of the social hierarchy. Despite these differences, there were striking similarities to the nation building projects of the two countries. Both were nationalist projects that placed national development and national defense (against the hostile rival on the other side of the demilitarized zone) in the foreground. National citizens were expected to contribute to their nation, and to make personal sacrifices for the greater good. Both national governments were authoritarian and used force to ensure that their populations were loyal and acquiesced to its developmental policies. And even as both received support from powerful allies, the two countries emphasized national sovereignty and independence. North Korea referred to national autonomy as “juche” (translated usually as “self-reliance”); but as Millett pointed out, the value (if not always the reality) of national self-reliance was equally embraced by South and North Korea.

Tuesday’s class focuses on North Korea, from the 1950s into the 1970s. Following the end of the Korean War in 1953, North Korea did surprisingly well in rebuilding the economy and society — and in terms of economic output, actually outpaced South Korea for most of the first two postwar decades. You can read the Charles Armstrong pdf for a concise overview of this period of postcolonial nation building/postwar reconstruction in North Korea. As we focus on N Korea, I want you to suspend your knowledge and preconceived understanding about present-day North Korea and approach the country as a former colony engaged in an urgent, popularly-supported course of non-capitalist decolonization, from the standpoint of the 1950s-1970s. As one recent historian of North Korea puts it: “It is within this history of [global, 19th-20th century] modernity that we must situate North Korean history–as a critique of capitalist colonial modernity, rather than a failed modernist project from the vantage point of [21st-century] postmodernity” (Suzy Kim, 2014).

Note 2: You will be examining either When We Pick Apples or Thursday’s film, Parade of Wives, in the upcoming short essay, which is due October 1. The essay will be a detailed scene analysis. You will select the scene (from one of the two films). It should be an important scene that connects to the broader message of the film, and that you can situate within the broader context of nation building/decolonization in Korea. So as you watch Tuesday’s film and Parade of Wives, keep an eye out for key scenes that seem particularly interesting to you. More information on the essay to come.

When We Pick Apples

The film for Tuesday’s class is When We Pick Apples (1971). From our perspective, at first glance, the film may appear to be a work of low production quality that is laden with state propaganda, and that is overly dramatic. But from the perspective of 1971 North Korea, When We Pick Apples was a blockbuster with star power, beautiful scenery, and optimism for the future. I am assigning the movie in order to provide a sense of the optimistic official view. The message: North Koreans had made great strides over the preceding 18 years (at the time that the film was made), and would continue to make progress, as long as everyone contributed and observed the principles and plans laid out by the government–and by the Great Leader Kim Il Sung.

The film takes place in the 1971 present, in the rural area of Pukchong. Pukchong has been developed into a prosperous rural locale, thanks to the hard work of the villagers and the guidance of the Great Leader, Kim Il Sung. Ten years earlier, the Great Leader had instructed the villagers to turn their home locale into an apple-producing region. Pukchongers took the instruction and ran with it. The film was made to celebrate Pukchong emergence as a major apple producer. While this ten-year segment is at the heart of the narrative, keep an eye out for how the film presents selected aspects of the North Korean “master commemorative narrative.” What are the past period with high “commemorative density”? How does Kim Il Sung figure into the master commemorative narrative? What is his role?

The cultural aesthetic of When We Pick Apples will be new to most of you. Soak it all in, while trying to see and understand all that is going on in the film. It is a propaganda film released that contains messages about: (1) the forward movement of NK’s economic development in the 1950s-1970s under the guidance of the “Great Leader”; and (2) the need to remain committed to one’s hometown and to NK at a time when the country’s economy was just beginning to show signs of slowing down. North Korea of the 1950s-70s was certainly authoritarian, but the North Korean government did not have total control of its people, as is often assumed. It was, in part, for this reason that North Korea increasingly invested in the production of propaganda films (and operas and other cultural products) in the late 1960s. Also, the proliferation of propaganda in the late 1960s and 1970s sought to solidify the “master commemorative narrative” in which N Korea was achieving a socialist decolonizing triumph.

The third assigned material is a speech given by Kim Il Sung on Pukchong. The film celebrates the great progress in fruit cultivation that was made in the region. On the other hand, the speech is interesting because it shows how Kim Il Sung connected fruit cultivation in the region to the country’s broader plans for agricultural production–including exporting North Korean fruits abroad. An interesting fact: the film When We Pick Apples was itself a cultural export — and was received with enthusiasm in China. Note: The pdf is locked so I was unable to extract the assigned pages. You’ll have to scroll down to p. 111 to get started.

Tips on viewing

- Keep your eye out for the dichotomy between complacency and striving. Complacency corresponds to the status quo–and the existing leadership–in the village depicted in the film. Striving and innovation corresponds to the younger characters, who are constantly trying to improve conditions in Pukchong — even though the village has already made great strides in the preceding decade. This desire to strive at the local level was analogous to the urgent task of building upon the ongoing North Korean project of revolutionary nation building revolution.

- Criticism and self-criticism. This was a common feature of communist societies, especially in East Asia. At their worst, criticism/self-criticism were central to “struggle sessions” in which people were publicly denigrated and humiliated. Struggle sessions could (and sometimes did) devolve into brutal cases of mass politics (for example, the Cultural Revolution in China). But criticism/self-criticism was also an everyday part of life in which individuals/groups reflected on their own shortcomings in a specific instance (say, a work project) with the aim of improving/reforming one’s mindset and one’s actions and contributing more effectively to a collective task. You’ll see aspects of criticism/self-criticism in the movie.

Decolonization

Decolonization encompasses a number of ideals, movements, and processes. Among them are:

- The desire of a colonized people to win national independence–and after that, build an independent, democratic, modernized, and prosperous nation-state.

- Decolonization did not end with the establishment of a new, postcolonial nation-state because it also encompassed:

- The desire to overcome differentials in economic, military, and diplomatic power between one’s own postcolonial nation-state and advanced global powers.

- The desire to modernize the essential aspects of one’s own national culture, while overcoming the perceived (not actual) flaws/shortcomings of one’s own national culture. The updating (of one’s one cultural traditions) and the selective adaptation of culture from Euro-America have been regarded as crucial to maintaining cultural integrity in the process of economic, political, social, and technological modernization.

- The historical wave of decolonization from the 1940s-1970s. The formation of dozens of postcolonial nation-states in this period coincided with the peak decades of the global Cold War. Former colonies had to stake out a position in relation to the “free world” bloc and the “communist bloc.” Some sided with the former. In Asia, these postcolonies include the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, South Vietnam, and Taiwan. Other Asian countries, such as North Korea, North Vietnam, and the People’s Republic of China (which had been partly colonized by Japan before 1945). Still other countries in Asia sought to pave a nonaligned position between the two global power blocs, such as Burma, India, and Indonesia. Alignment with a power bloc (or seeking to maintain nonalignment) were strategies to continue making progress in decolonization (along the lines of the two non-solid bullet points above).

This week, we are examining the official, state-driven projects of decolonization orchestrated) by the North Korean state and the by the South Korean state. These were rival decolonization projects. Each deemed itself to be the legitimate state for all Koreans, while regarding its rival as the illegitimate state of half the Korean people. We will examine institutionalized decolonization in the North and in the South. In the next module, we will explore decolonization beyond institutional decolonization) by focusing on the South Korean democratization movement — which called into question the legitimacy of the S Korean state, and sought a more genuine decolonization that was truly for “the people.” Here, the official nation memory in S Korea was challenged by a “counter-memory.”