Analysis of Percent Acetylsalicylic Acid (Aspirin) in a Mystery Tablet

TOC/Help. Click here to expand/hide

Overview

Background

Pre-lab work

Experimental

Post-lab work

![]() For help before or during the lab, contact your instructors and TAs (detailed contact information are found on Canvas).

For help before or during the lab, contact your instructors and TAs (detailed contact information are found on Canvas).

Overview

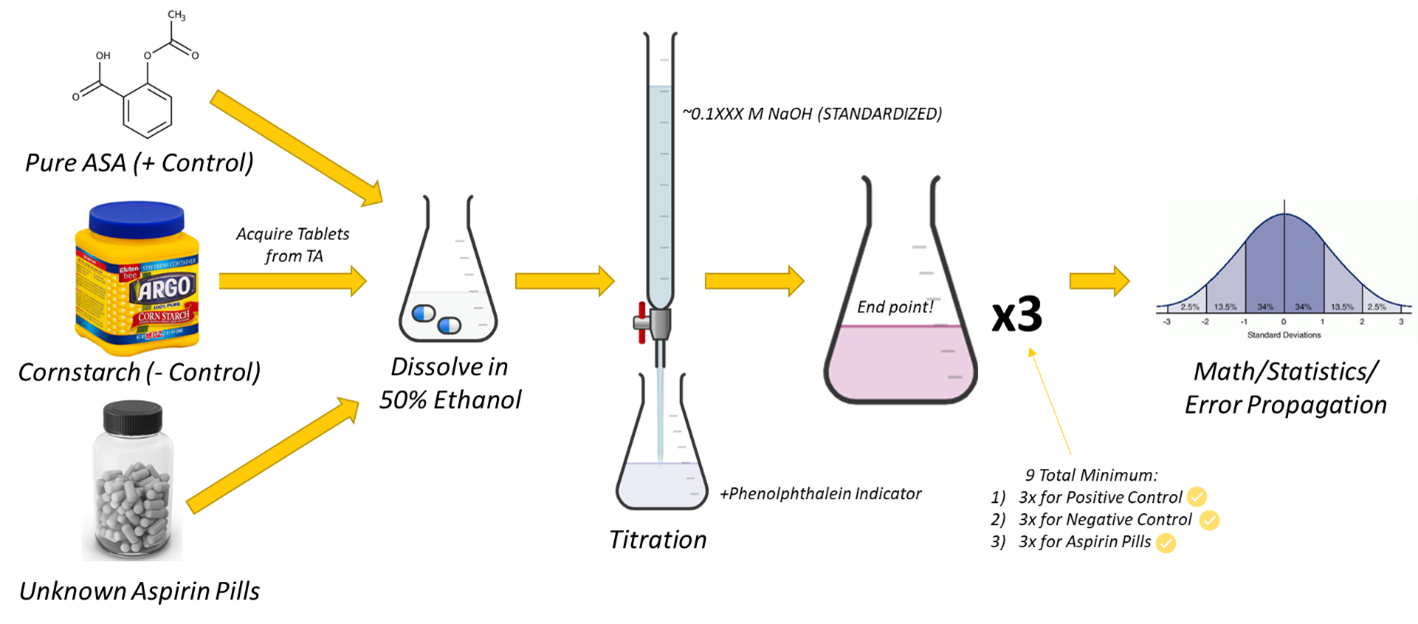

Students will calculate both absolute and relative concentrations of acetylsalicylic acid in a mystery aspirin tablet by way of a direct titration. Using statistics, students will report (with confidence) the concentration of acetylsalicylic acid and compare it to an expected concentration.

Learning Objectives

- Apply a titration technique for making a chemical measurement using a colorimetric endpoint.

- Employ a control to validate a method of chemical measurement.

- Practice converting concentration units to correctly calculate the concentration of an analyte in a sample.

To cite this lab manual: “Analysis of Percent Acetylsalicylic Acid (Aspirin) in a Mystery Tablet”. A Manual of Experiments for Analytical Chemistry. Department of Chemistry at UW- Madison, Summer 2024.

Visual Abstract

Background

Quality assurance (QA) refers to the planned and systematic process by which a product is produced and tested for its intended purpose. The use of QA fits well into the practice of analytical chemistry. Experimental methods used to test products must collect the correct data, must analyze those data minimizing error, and the result should provide valuable feedback to producers on the quality, purity, and reproducibility of the production process.

The chemical composition of any over-the-counter medicines are under high scrutiny, as many are taken for life saving measures. For example, when taken at a low dose, aspirin can prevent heart attacks or pre-eclampsia (i.e., high blood pressure in pregnant women). As one of the most widely used and commonly prescribed nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), aspirin is on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Model List of Essential Medicines.

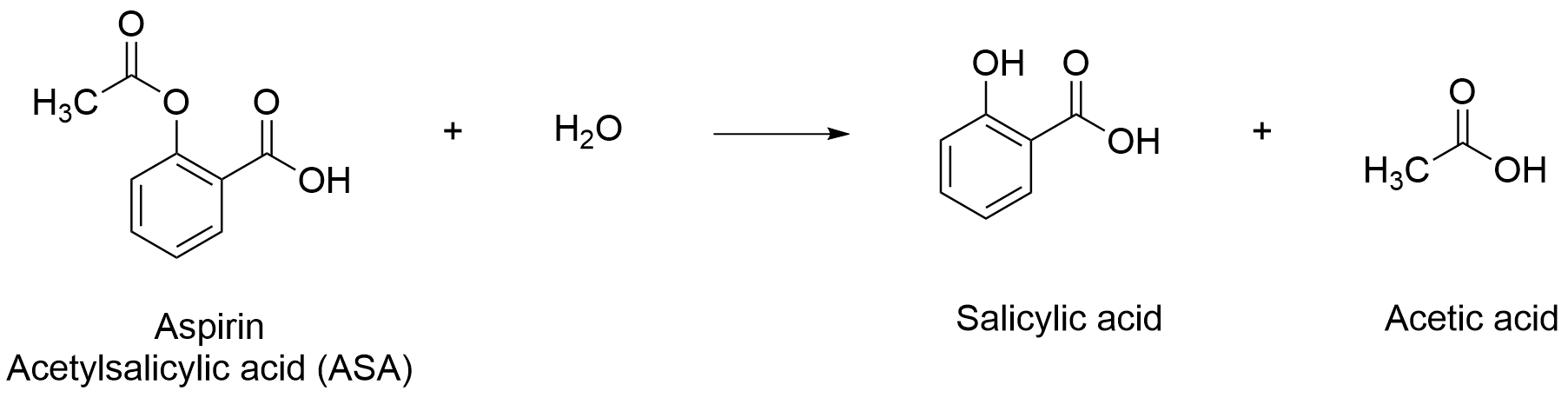

The active ingredient of aspirin is a single compound, acetylsalicylic acid (ASA, 180.159 MW), a modified form of salicylic acid. In pill form, ASA is mixed with other inactive ingredients, including corn starch and cellulose, which serve as “fillers” to allow for the packaging, storing, and ingesting of ASA for consumer use. Aspirin tablets are sold at varying dose levels, including (for adults) “low doses” (81 mg/tablet), “regular strength” (325 mg/tablet), and “high doses” (500 mg/tablet). ASA is shelf-stable, but, when exposed to water for a lengthy period of time or heated, it can degrade into salicylic acid and acetic acid (Figure 1). For this reason, you can often find a small package of desiccant in pill containers, and the storage instructions recommend keeping the bottle at room temperature.

How can we quantify the amount of ASA present in a tablet? Weak acids react completely and quickly with strong bases, like sodium hydroxide (NaOH). Equation 1 illustrates the reaction, with the acidic/protonated form of ASA being called H-ASA and the deprotonated form ASA:

| H-ASA(aq) + OH‾(aq) ⟶ ASA‾(aq) + H2O | (1) |

Designing an experiment for QA purposes requires careful considerations to both the preparation of the sample as well as designing a set of experimental controls that evaluate the chemical measurement itself. For example, sample preparation should avoid premature degradation of product and the analyte must fully dissolve to participate in the reaction described in Equation 1. The degradation of ASA happens at high temperatures and with water exposure for longer periods of time (~1 week). By freshly making the solutions of ASA and avoiding heat, the sample should be okay.

Secondly, PubChem is a great resource to varify that ASA is soluble. In section 3.2.7, we see a range of solubilities from <1 mg/mL to 10 mg/mL in water. This isn’t ideal for our experiment, as ASA will not fully dissolve in water, which will compromise the result. The addition of ethanol improves the solubility of ASA. Thus, by choosing a 50:50 mixture of ethanol:water and giving some time to the dissolution process, results are likely achievable. While ASA is soluble under these conditions, other matrix components may not be. These components won’t interfere with the chemistry; they may make the solution appear cloudy and thus, more difficult to determine the colorimetric endpoint.

Considering the solubility highlights the fact these aspirin tablets are not 100% ASA, it is important to report both the absolute concentration (i.e., the mg of ASA present in the tablet) and the relative concentration (i.e., the percent composition of ASA in the tablet). Percent composition is calculated by taking the mass of solute (msolute) divided by the total mass (mtotal), or in this case, the mass of ASA divided by the total mass of tablet(s).

| [latex]\% \; composition = \left( \dfrac{m_{solute}}{m_{total}} \right) \times 100\% = \left( \dfrac{m_{ASA}}{m_{tablet}} \right) \times 100\%[/latex] | (2) |

In experimental design, both positive and negative controls are essential components of interrogation and method to minimize error. They serve different purposes and provide different types of information. A positive control is a condition or sample in an experiment intentionally designed to produce a known or expected result. A positive control validates the experimental setup and procedures. In QA practices, a positive control result validates that the experimental conditions are appropriate and that the experiment can detect the desired effect. In the case of measuring ASA in a tablet, a good positive control would be a carefully measured sample of pure ASA. If weighed out exactly each time, you can both assess the accuracy of the titration (by comparing the measured amount of ASA versus the calculated amount of ASA) and the precision of the titration (by looking at magnitude of the standard deviation).

A negative control is designed into an experiment to assess non-specific effects or potential artifacts of the sample matrix. These artifacts are interferences, or species that will increase (or decrease) the amount of something we measure (i.e., ASA). Negative controls provide a baseline against which to compare the experimental results and helps us to determine what '0' is; in terms of error types, this is considered a systematic error (i.e., one we can account for). If we are able to know how much interference is present, we can subtract that amount from the measurement of our sample and get a more accurate final answer. For our system, any interference would be caused by everything else in the tablet besides the ASA. Thus, for our experiment, a reasonable negative control could be corn starch, a known component of the tablet, which is manipulated in the same way as the tablet you plan to analyze.

Both positive and negative controls are critical in experimental design to ensure the reliability and validity of the results. We will implement both types of controls in this experiment to fully characterize the colorimetric titration of ASA with NaOH.

In previous labs, you framed experimental results as an average of at least three measurements, which you report with a standard deviation. A standard deviation quantifies the spread of data within a set of measurements. However, while the inherent error associated with the reported results can be inferred, the standard deviation does not reveal the specific sources of error introduced during chemical measurements and manipulations. Propagated error (also known as propagation of uncertainty) considers the uncertainties in the measured variables, their correlations (if applicable), and the mathematical relationships among them. The analysis provides an estimate of the uncertainty in the final calculated value, accounting for the contributions from each variable.

In summary, standard deviation quantifies the spread of data within a set of measurements, while propagated error estimates the uncertainty in a calculated result that depends on multiple measured variables. The lecture portion of the course will cover the mathematical derivations for the basis of propagated error more fully, and you can find additional information in Appendix B (page AP-3) of the Harris Quantitative Chemical Analysis text (10th Edition).

Table 1 summarizes how to manipulate the errors associated with the various chemical measurements. In this lab, besides exploring the QA of the proposed method for analyzing the amount of ASA in a tablet, you will discover whether the propagated uncertainty (associated with the titration manipulations of the analysis) is comparable to the standard deviation to the averaged result.

| Function | Uncertainty | Function | Uncertainty |

| [latex]y = x_1 + x_2[/latex] | [latex]e_y = \sqrt{e^2_{x_1} + e^2_{x_2}}[/latex] | [latex]y = x^a[/latex] | [latex]\% e_y = a \% e_x[/latex] |

| [latex]y = x_1 - x_2[/latex] | [latex]e_y = \sqrt{e^2_{x_1} + e^2_{x_2}}[/latex] | [latex]y = \log x[/latex] | [latex]e_y = \dfrac{1}{\ln 10} \dfrac{e_x}{x} \approx 0.43429 \dfrac{e_x}{x}[/latex] |

| [latex]y = x_1 \cdot x_2[/latex] | [latex]\% e_y = \sqrt{\% e^2_{x_1} + \% e^2_{x_2}}[/latex] | [latex]y = \ln x[/latex] | [latex]e_y = \dfrac{e_x}{x}[/latex] |

| [latex]y = \dfrac{x_1}{x_2}[/latex] | [latex]\% e_y = \sqrt{\% e^2_{x_1} + \% e^2_{x_2}}[/latex] | [latex]y = 10^x[/latex] | [latex]\dfrac{e_y}{y} = (\ln 10) e_x \approx 2.3026 e_x[/latex] |

| [latex]y = e^x[/latex] | [latex]\dfrac{e_y}{y} = e_x[/latex] | ||

| Note: x represents a variable and a represents a constant that has no uncertainty. ex/x is the relative error in x and %ex is 100 × ex/x. | |||

Lab Concept Video

There is currently no concept lecture video for this lab.

Pre-lab Work

Lab Skills

Review these lab skills videos prior to lab.

click here to hide the video playlist (for printing purpose).

Key Takeaways

- Titrations take a lot of patience and practice to hit the end point correctly.

- By using volumetric glassware, we can improve the accuracy and precision of our measurements.

Prelaboratory Exercises

- Assuming you will be analyzing a “regular strength” aspirin tablet, calculate the volume of your standardized NaOH (~0.1XXX M) you would need to analyze 1 tablet. Based upon this information (and the optimal range of the buret, 35-45 mL), how many tablets will you use per titration? Incorporate that number into your procedure. (This is just an estimate! Be prepared to adjust the number of pills used for the sample to utilize the optimal buret range.)

- Assuming you will be analyzing a “regular strength” aspirin tablet (and that their average weight is 0.36 grams per tablet), what is the expected percent ASA in the tablet?

Before You Take The Quiz on Canvas

- Review the chemistry and stoichiometry of the titration reaction.

- Be able to calculate how much ASA should be used for the titration of the sample given a set of initial parameters: approximate mg of ASA, approximate concentration of NaOH, and a target end point volume.

- Be able to calculate the precise weight % of ASA of the sample given a set of titration data: mass of sample used, concentration of NaOH, and the volume required to reach the end point.

- Be clear on the use of experimental controls (both positive and negative) in characterizing an experimental method.

Experimental

You will have a maximum of eight tablets available to you for the lab period. Please grab what you need for one experiment at a time. Please return unused tablets to the stockroom. Tablets should NOT be ingested. Be sure to accurately record the concentration of standardized NaOH provided.

STORY: After sitting through lecture, you have a massive headache. You have a big bottle of aspirin on your shelf, but the label fell off! You don't remember how much aspirin there is per tablet. You decide to determine the amount of aspirin per tablet by using a NaOH titration. As a bonus, titrating is so much fun that it will make you feel a little better too.

A. Control Analyses

Positive Control:

- Using the estimated amount of ASA calculated in the prelaboratory exercises as guidance, accurately weigh out a representative sample of pure, reagent grade acetylsalicylic acid using the analytical balance. Quantitatively transfer the weighed amount to a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask. Dissolve with approximately 75 mL of 50:50 ethanol:water solvent. Try to weigh out the exact amount you calculated (or the same each time) to help assess the precision of the titration.

Pro Tip #1: Heat speeds the degradation of aspirin, so do not heat the solution.

- Add three drops of phenolphthalein to the flask.

- Titrate the result with 0.1XXX NaOH.

- Record the volume of NaOH at the end point to the 100ths place.

- Capture three measurements of the positive control sample.

Pro Tip #2: Aspirin slowly degrades at medium-to-high pH. The titration’s endpoint will be clear and sharp if the tablet is completely dissolved, but the color will fade over time. A solution that holds a pink color for over a minute can be considered fully titrated.

Negative Control:

- Assume the remaining mass of a regular strength tablet is made of corn starch. Using what you know about the regular strength tablet, estimate a reasonable mass of corn starch to use as a negative control. Using a similar procedure as described for the positive control, titrate the sample and be sure to collect your result in triplicate. Try to weigh out the exact amount you calculated (or the same each time) to help assess the precision of the titration.

B. Tablet Analysis

- Obtain mystery tablet(s) for one experiment from your TA or the stockroom, as determined in Prelaboratory Question #1.

- Weigh the tablet(s) and record the total mass.

- In a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask, dissolve the tablet(s) in about 75 mL of 50% ethanol. Swirl the flask vigorously for several minutes to allow the tablet(s) to completely dissolve. Remember that some of the inactive ingredients will not fully dissolve.

- Add three drops of phenolphthalein indicator to your 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask.

- Titrate with your standardized NaOH (~0.1XXX M).

- Record the volume of NaOH used to the 100ths place.

- Repeat the experiment (steps 1-6) at least two more times (n=3).

- Feel relief.

Post-Lab Work Up

Results/Calculations

Fill out the answer sheet for this experiment completely. Answer the following post-lab questions.

- Calculate the average (and standard deviation) in mg of ASA for both the positive and negative control.

- The standard deviation will be meaningful if each of the replicates had approximately the same amount of ASA weighed out. If you weight out slightly different amounts, though, please still report the number.

- Calculate the mass of aspirin per tablet in milligrams (mg) and your standard deviation. This is the value given on the label of commercial products.

- Calculate the mass percentage of aspirin per tablet. This is the kind of value used by chemists when dealing with a bulk material.

- Report your result with the error propagated, assuming the error is random in nature. Consider the standard error of each tool used in the experiment to make a volume or mass measurement. Lecture activities and slides as well as Appendix B of the Harris text (10th Ed) may be helpful in propagating error reflected in the result. You only need to propagate the error of one trial.

- In the reflective summary portion of the lab manual, discuss these elements of the experiment:

- Justify ways the experiment collected the desired data/information.

- Describe ways you interrogated the experiment to minimum error.

- Summarize the experimental findings that would be of particular interest to producers and/or consumers of aspirin tablets.

- Using the weight % composition results as an example, compare the errors reported by the standard deviation versus the propagated error.

Challenge Questions

Challenge questions are designed to make you think deeper about the concepts you learned in this lab. There may be multiple answers to these questions! Any honest effort at answering the questions will be rewarded.

- Describe how you would change your procedure if you were working with a low dose aspirin tablet. Would you need to change the number of tablets? The titration reaction? The colorimetric indicator? (Consider the supplemental information for more guidance.)

- As shown in Figure 1, ASA breaks down into salicylic acid and acetic acid. Both salicylic acid and acetic acid are weak acids (pKa = 2.97 and 4.76, respectively), and they also can react with NaOH when titrated to completion. Predict how the mole-to-mole ratio for the overall titration reaction would change as the sample degraded, including:

- Minimally (<1%) degraded

- Half (~50%) degraded

- Fully (~100%) degraded

Lab Report Submission Details

Submit your lab report on Canvas as 1 combined PDF file. This submission should include:

- The completed answer sheet.

- Your lab notebook pages associated with this lab, which should include answers to the post-lab questions and challenge questions.

The grading rubric can be found on Canvas.

Supplemental Information

Why a titration experiment is a good option for the analysis of acetylsalicylic acid

Fundamentally, ASA is a weak acid with a pKa of 3.5 (where pKa = -log Ka). K, or equilibrium constants, tell us if a reaction will go to completion. A K-value much greater than one (>>1) indicates the reaction strongly favors products. The reaction under investigation involves acid-base chemistry, and chemists have determined standard equilibrium constants for acid (and base) dissociation reactions. The standard acid dissociation constant, or Ka, for ASA is 3.16 × 10-4. Kw is defined as the water dissociation constant and is given a value of 1 × 10-14. As written, equation 1 reflects the chemistry in terms of the hydroxide ion, which acts as a base receiving a proton from the acidic form of ASA. The reverse of the reaction described in (1) represents the base dissociation constant, or Kb. At equilibrium conditions, Kw = Ka·Kb. In general chemistry, you learned to write the reaction quotient by considering the states and concentrations of products over reactants. In the case of (1) the result looks like the following:

[latex]Q = \dfrac{[ASA^-]}{[H-ASA][OH^-]}[/latex] (remember H2O becomes a value of 1)

At equilibrium, Q approaches Krxn. And therefore, using what is known about the equilibrium constants for the system, we can prove reaction (1) will go to completion:

[latex]K_{rxn} = \dfrac{1}{K_b} = \dfrac{1}{\left( \dfrac{K_w}{K_a} \right)} = \dfrac{1}{3.16 \times 10^{-11}} = 3.16 \times 10^{10} \gg 1[/latex]

Considering we have a 1-to-1 ratio (see the coefficients of all compounds in Equation (1), we can assume that the moles of NaOH added to the solution are equivalent to the moles of ASA present in our solution, which can be inferred as the moles of ASA present in a tablet.

Why phenolphthalein is a good indicator choice

A buret is a perfect tool to deliver a precisely measured amount of NaOH. However, there must be some sort of indicator or measurement to ensure the reaction has gone to completion. The equivalence point is defined as the ideal point in a titration where the moles of titrant added (in this case, NaOH) perfectly matches the moles of ASA present in solution. As a practical matter, chemists realize that experimentally measuring the ideal equivalence point is impossible, and therefore reference the endpoint of the titration to differentiate the experimental from the theoretical result. In the case of acid-base titration reactions, the endpoint can be measured by monitoring a pH change (using a pH probe) or by using a colorimetric indicator that changes color at the pH where the equivalence point is realized. Colorimetric indicators like phenolphthalein or bromocresol green are examples you likely have used in previous chemistry experiments. The selection of indicators is not random—indicators are chosen based upon the pH of the solution at the equivalence point. When going from acidic-to-basic pH, bromocresol green changes from yellow to blue, specifically in the pH range of 3.8-5.4.1 Phenolphthalein changes from clear to pink when transitioning from an acidic to a basic environment, specifically in the pH range of 8.0-9.6.1 But how can one know the equivalence point of the NaOH-ASA titration? By modeling the titration curve (yes, using theory and math!), the estimated end point pH is ~8. That means phenolphthalein as a colorimetric indicator will be perfect choice for this titration. We will explore modeling titration curves later in this course.

References:

- Harris, D. C. & Lucy, C. A. Quantitative Chemical Analysis, 10th ed.; W. H. Freeman: New York, NY, 2020, page 62.

Please use this form to report any inconsistencies, errors, or other things you would like to change about this page. We appreciate your comments. 🙂 (Note that we cannot answer questions via the google form. If you have a question, please ask your instructor or TA.)