Lab 2 Background

Introducing Mutation to the T7 Phage Genome

As discussed in Chapter 1, the T7 phage is an obligatory lytic phage that infects most E. Coli strains. To understand the mechanism of T7 phage infection and to study the virulence of the T7 phage, each group will construct and test one T7 mutant. The wild-type, unaltered T7 phage will be used as a baseline control for comparison.

In order to assemble a mutant T7 phage in this lab, the following steps have been done for you by the teaching team:

- Use PCR to fragment the T7 genome and introduce the desired mutation:

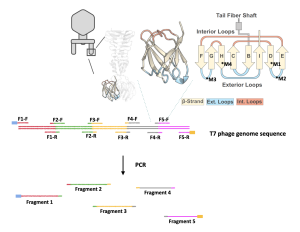

- The genome of the T7 phage is about 50 kilo-base pairs (kb), or 50,000 base pairs (bp), a considerably long stretch of DNA. To successfully express the T7 phage, its genome was broken into five pieces using PCR (see figure 2.1 below). More information on PCR can be found in the Background section of Lab 3.

- This allows us to obtain DNA fragments with manageable lengths for genome assembly and expression. The process also allows us to introduce the desired mutation into the T7 phage genome by making copies of the genome fragments with the mutation.

- Use PCR to fragment the expressing vector pRS315:

- A vector, or plasmid, is an artificial circular extrachromosomal DNA where genes can be inserted and subsequently expressed in a desired organism.

- In this research project, we will use the vector pRS315.

- This vector is used because it has several important features:

- It contains a type of DNA called yeast artificial chromosome (YAC), which allows the T7 phage genome to be reassembled in yeast cells.

- It can carry and deliver the mutant T7 phage genome into bacteria.

- It has features that allow for proper T7 phage gene expression in the bacteria, which will lead to phage particle production and host lysis/killing.

- Similar to the T7 phage genome, the DNA sequence of the pRS315 vector was broken into 3 fragments using PCR (see figure 2.2 below).

In lab 2, you will be given a tube of DNA mixture that contains 8 DNA fragments – 5 that constitute the mutated T7 bacteriophage genome and 3 the pRS315 vector.

Yeast Artificial Chromosome (YAC)-Based Genome Assembly

YAC is a genetically engineered chromosome originated from yeast and can be used to assemble and amplify DNA in yeast cells. To accomplish a YAC assembly, one or more DNA fragments and the YAC need to be taken up by yeast cells using various methods. In our case, a method called transformation will be used to “insert” DNA fragments into yeast cells. Once inside, yeast cells identify the features on the fragments and assemble them into one circular DNA. Because YAC mimics endogenous yeast chromosomes, yeast cells will assemble and amplify the inserted DNA (in other words, yeast cannot distinguish its own chromosomes and YAC, and will replicate YAC as if the YAC is the yeast’s own chromosome). The amplified DNA will then be extracted from yeast cells for later use.

In the Biochem207 laboratory, we will put the T7 bacteriophage mutant genome fragments and the YAC fragments (pRS315) into yeast cells. Yeast cells will then assemble all the fragments in the correct order into one vector (circular DNA) and then amplify the T7 genome, as shown in the figure below.

Culturing Yeast

Yeast are single-celled eukaryotes commonly used in biological research. Yeast grows fast and has well-defined genetic systems. It is also commonly used for purifying eukaryotic proteins.

Yeast is generally cultured in either liquid media or solid media (plate) at 30 °C.

When liquid culturing is used, the growth of yeast cells experiences four growth phases: lag, log, stationary and death.

- Lag phase: cells grow slowly when initially added to liquid culture. Depending on the media and the cells this can last many hours. Cells gradually speed up until they reach maximum growth in the log phase.

- Log phase: cells are growing at their fastest rate. This is almost always the correct growth phase to harvest cells for experiments. Mid-log is best, corresponding to an OD600 of 0.4-1 (for very sensitive experiments 0.5-0.8). During the log phase, cells grow with a defined doubling time – the time that the number of cells present takes to double. The doubling time varies with media and cell type – healthy cells growing in rich media at 30 °C have a doubling time of 90 minutes or less, but unhealthy or mutant cells can have doubling times of many hours.

- Stationary phase: growth slows down. OD600 is usually at 0.9-1.5

- Dying phase: cells die rapidly.

Measuring Yeast Cell Growth

This is done by putting 1 mL of cells in a disposable cuvette and reading the absorbance in a spectrophotometer. For OD600 reading ranging from 0.05 to 1.0, the reading is roughly proportional to cell number. For cultures with an OD600 reading above 1.0, one should dilute the culture in half (1 part of yeast culture and 1 part ddH2O) and re-measure.

Transformation

Transformation is the process by which exogenous DNA is introduced into a host cell, resulting in an inheritable change or genetic modification in the host cell. During transformation, host cells, in this case, yeast cells undergo both chemical and heat treatment to achieve competence, a state in which cells can easily uptake DNA from their surroundings.

To achieve competence, cells are usually pre-treated with chemicals lithium acetate and polyethylene glycol (PEG). The exact mechanism is not well understood, but it is thought that these chemicals can help to attract and retain DNA. After the desired DNA is added to the solution containing the host cells, cells will be heat-shocked at 42 °C. The elevation in temperature allows the host cell membrane to become porous, allowing DNA to be taken up by the cells.

In a future lab, we will use electroporation, another method of transformation that uses electrical pulse to temporarily creates pores on cell membrane, to transform bacteria cells with desired DNA.

Competent host cells are very fragile and must be treated with care. They should be mixed gently. The timing and temperature of heat shock must be precise; if kept too long at a high temperature, cells will die. Please also use an aseptic technique throughout the experiments to avoid contamination.

Aseptic Technique

Aseptic technique refers to the methods used to prevent contamination with microorganisms. Nonsterile supplies/reagents, careless laboratory habit (such as not close lid of tip box after using) and dirty work surfaces are all sources of biological contamination.

Aseptic technique is designed to provide a barrier between the microorganisms in the environment and the sterile cell culture.

Here is a non-comprehensive list of aseptic technique in a biochemistry laboratory:

- The work surface should be uncluttered and contain only items required for a particular procedure.

- Use a Bunsen burner for flaming when plating cells.

- Wash hands before and after working with cell cultures.

- Wear clean gloves and change often.

- Wear lab coat and protective eye wear.

- Use sterile glass or plastic pipettes when working with liquids, and use each pipette only once to avoid cross contamination.

- Always cap the bottles and flasks after use.

- Keep cell containers (flask, dish) closed until use; close the cell containers immediately after use.

- Perform experiments as rapidly as possible to minimize contamination.

- Minimize talking or singing when performing sterile procedures.

Reference

Ando, H., Lemire, S., Pires, D. P., & Lu, T. K. (2015). Engineering Modular Viral Scaffolds for Targeted Bacterial Population Editing. Cell Syst, 1(3), 187-196. doi:10.1016/j.cels.2015.08.013

Huss, P., Meger, A., Leander, M., Nishikawa, K., & Raman, S. (2021). Mapping the functional landscape of the receptor binding domain of T7 bacteriophage by deep mutational scanning. Elife, 10. doi:10.7554/eLife.63775