Made in America with Foreign Parts

25 Quilt

|

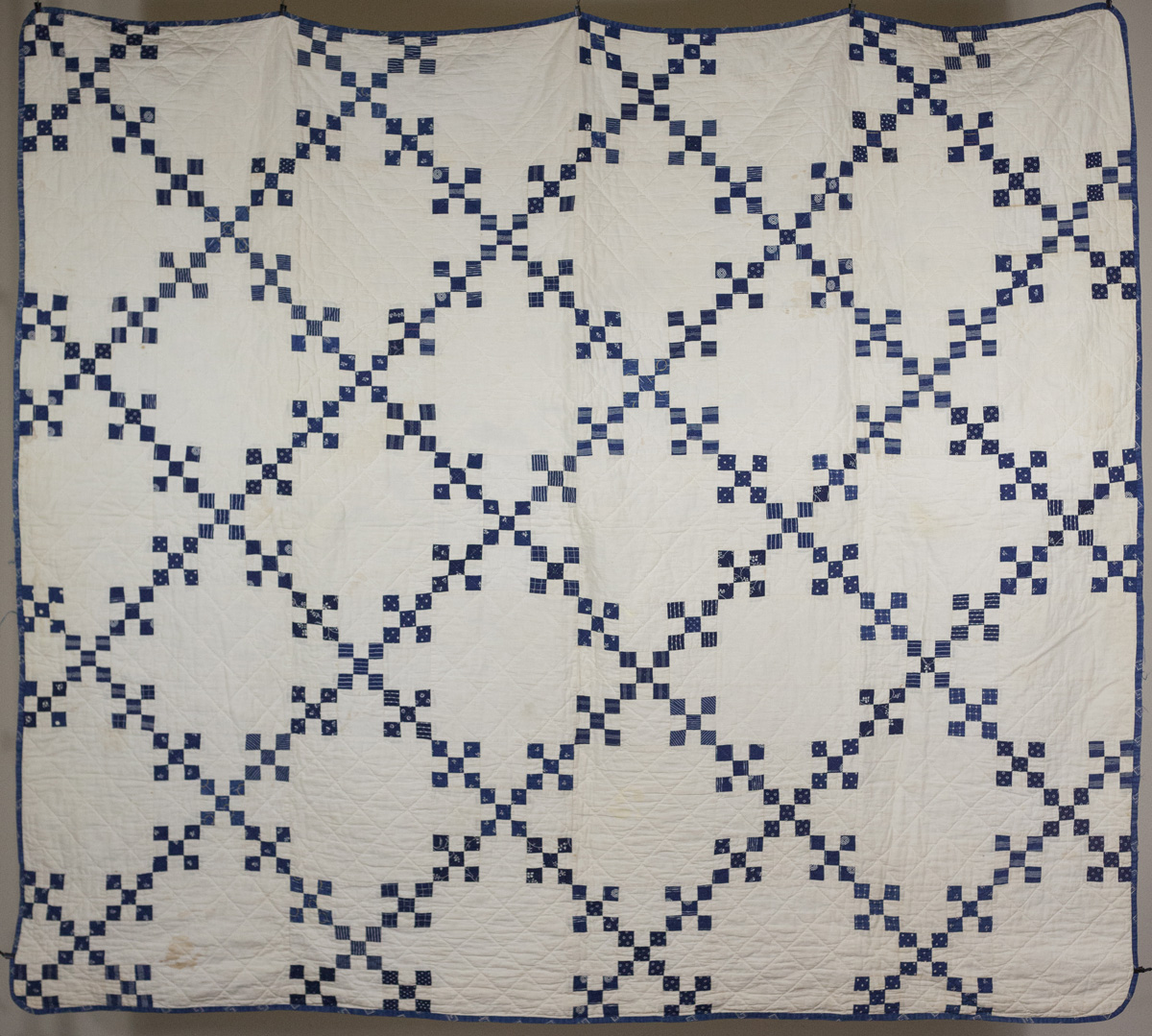

Quilt American Ellen Sweet, c.1865 Cotton Gift of Delma Donald Woodburn Estate MHAHS 2002.002.0367 |

Late 19th century women’s magazines promoted household craft and decoration in a reactionary movement against the Industrial Revolution’s factory-line production of undifferentiated, machine-made items. Young ladies were expected to master these domestic skills, and common household goods often became their palette for artistic expression. Parlors and family spaces were filled with this kind of craft, like this 1865 quilt created by the young Ellen Sweet of the Town of Springdale.

For a complete essay on this object, click here.

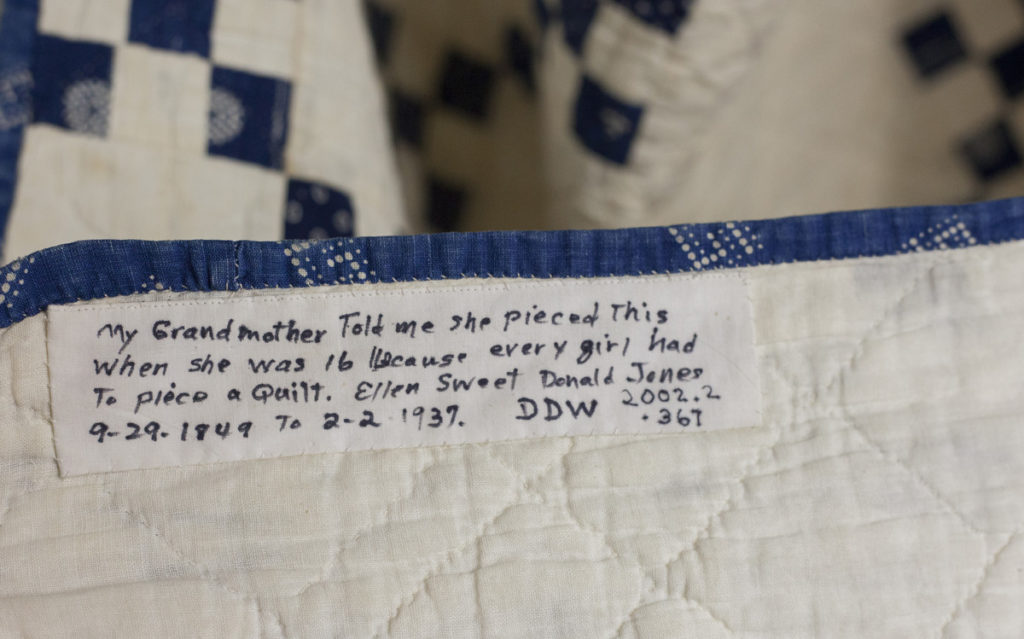

Despite the countless technological and aesthetic developments of the past 150 years, few objects possess the degree of personal resonance inherent in a warm quilted blanket. Though centuries pass, it ties us to peoples long before us through our shared basic needs for warmth, home, and family. Ellen Sweet Donald Jones stitched this quilt when she was only 16 years old. Sweet’s granddaughter, Delma Donald Woodburn, wrote of the quilt, “My grandmother told me she pieced this when she was 16 because every girl had to piece a quilt” (Figure 1.) Set alongside the artistic quilts of more mature seamstresses, her work might seem unpracticed and simplistic because this quilt documents Sweet’s quilting education. The popular “Irish chain” design constructed in a double nine patch pattern in which nine block patches construct larger blocks, was a common and easy design particular favored by learners, while the combination of indigo patterned calicos and white squares were affordable fabrics for a large immigrant family new to the Midwest.

Sweet moved to the Springdale township of Wisconsin in 1855 at the age of six. She arrived with her family of eight from Chautauqua County in New York at a time when Springdale didn’t even have a general store. Moving to a small town before the age of ready-mades demanded that the family be self-sufficient in producing their own domestic goods such as blankets or quilts and clothing. The family chores were divided largely along gender lines so that Ellen’s mother, Sally Clark Sweet, would have been responsible for producing blankets so that her family would have a warm bed.

She was also responsible for teaching her daughters, including Ellen, how to sew so that she could help provide for her someday married household. Three years after she finished the quilt, Ellen married local farmer John Donald. We might assume that she continued to develop her skills as a quilter since technologies like the sewing machine and ready-mades were still not widely available.

Oftentimes, quilts such as Ellen’s go unremarked upon because they possess simple designs typical of American quilts of the mid-nineteenth century and betray an unpracticed hand; but Ellen’s quilt is special for these reasons because it represents the passage of knowledge from one generation of women to the other. Though her quilt does not possess the ingenuity and creative freedom exercised in seasoned seamstress works, Ellen’s material, the common indigo blue dyes and affordable calico, refer to her industrious use of nearby resources. Ultimately, Ellen’s ordinary quilt tells the extraordinary story of domestic self-sufficiency practiced in rural America.