Supplemental Resources: Supporting Student Learning

Acknowledging Responses to Political Events

This resource was originally composed to support those teaching during the 2020 election cycle. It draws on conversations initiated by instructors who were working to balance complex values that were sometimes in conflict with one another. On the one hand, they sought to honor learners’ needs and respect the fact that the classroom is never divorced from the world. On the other, they valued cultivating a supportive learning environment during a cultural moment when interpersonal tensions around political beliefs could escalate especially quickly. While elements of this resource are anchored in the details of the 2020 election, the reflection processes and questions it includes may translate into current-day teaching contexts in which global or local events may be particularly present to learners and instructors alike.

Emotions play a central role in learning. Advances in affective neuroscience have shown that emotional states are intricately connected with the cognitive processes involved in perception, attention, learning, memory, reasoning, and problem-solving.[1] In a nutshell, how we feel in any given moment affects what, how much, and how well we learn. While we cannot predict nor control what specific emotions our students bring into the learning space, we can respond by creating environments where their emotions are acknowledged, validated, normalized, and honored as part of the learning process.

Acknowledgement, validation, and normalization of emotions are particularly important during this election cycle. As James Olsen from the Center for New Designs in Learning and Scholarship at Georgetown University put it, “Regardless of one’s political views, the 2020 election is unlike any other in recent history, and perhaps unique with regard to its potential impact on higher education. For a variety of reasons, anxiety runs high among our students—both undergraduate and graduate and in particular among marginalized student populations—and much of that anxiety is centered on or exacerbated by the elections.”[2]

The following steps will support you in planning a pedagogically-sound, compassionate response to enact in your learning environment during this election cycle – a response that begins with yourself, because what you do should honor and respect your personal, mental, emotional, and physical capacity in these times. Be honest with yourself, and remember that there are several resources and qualified support structures in place at the university for our students. You do not have to do it alone.

Page Navigation:

- Step 1: Self-reflection to identify your current bandwidth

- Step 2: Self-reflection to identify your pedagogical/disciplinary proximity

- Step 3: Explore the quadrant and pedagogical response best suited to your personal bandwidth and pedagogical/disciplinary proximity

- Closing Considerations

Step 1. Self-reflection to identify your current bandwidth.

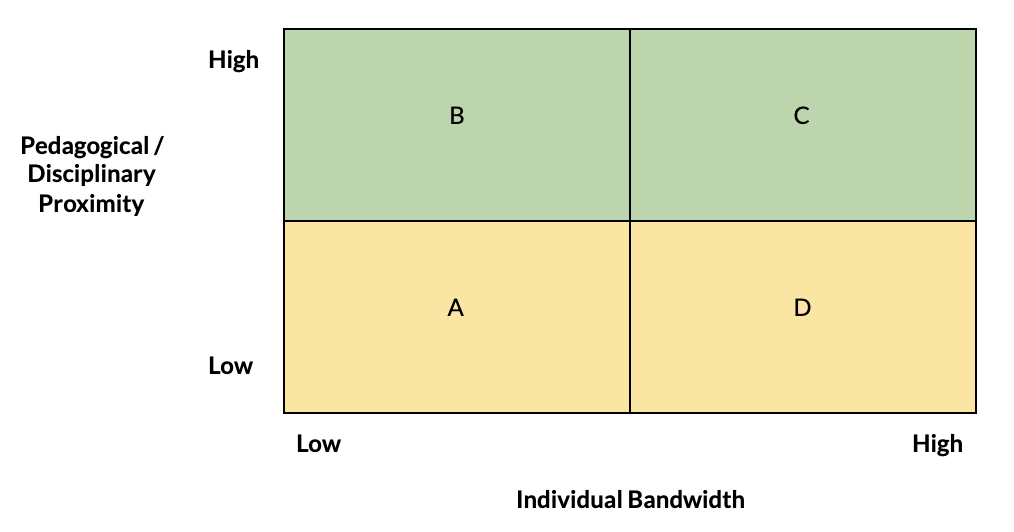

On the bandwidth axis in the graph below (x-axis), situate yourself on the spectrum between low and high. This process is not exact; low and high will naturally mean different things to each of us.

Screen-reader-legible media description

Here are some questions to support your thinking:

- Think about the day after the election. Picture yourself processing the outcome you were hoping for, the opposite outcome, or the period of uncertainty that is likely to persist after this unusual election. What feelings come up for you in each instance?

- What is the impact of these feelings on your ability to engage with others, specifically your students? Some of us may be able to quickly translate our feelings into productive pedagogical action (more on what that means later); some of us may need extended time and space to individually process before we are ready to engage productively with others.

- What is your experience – personal and professional – engaging in conversations about topics that may be deeply and overtly connected to the social identities and experiences of the participants in the room?

- What categories from your social identities (gender, immigration status, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, to name just a few) might weigh on your bandwidth to engage in this conversation with others?

Step 2. Self-reflection to identify your pedagogical/disciplinary proximity.

What is the proximity between your discipline and the outcome of this election? For example, if you teach music theory, the election outcome may not be as proximal to your discipline and content as it would be if you taught political science, international studies, gender studies, or sustainability studies.

On the pedagogical/disciplinary context axis in the graph below (y-axis), situate yourself on the spectrum between low to high. Each discipline will have varying degrees of contextual proximity and immediacy with the outcome of this election.

Step 3. Explore the quadrant and pedagogical response best suited to your personal bandwidth and pedagogical/disciplinary proximity.

Screen-reader-legible media description

Quadrant A and D: Acknowledge + Refer

At a minimum, on the days following the election, we should plan to acknowledge with our students that each of us is experiencing different emotional responses, and we should make an intentional effort to remind them about campus resources designed to support them during this time.

Here’s a sample script to support your thinking and planning – you are welcome to adapt it as you see fit to make it your own:

“Hi, All. I would like to start class acknowledging that we are officially in post-election time. The outcome (or the continued uncertainty) impacts each of us differently, and we bring ourselves to class today with varying feelings and emotions. I want you to know that however you are feeling, you are welcome in this space. And I want to thank you for showing up to continue our learning today. I also want to remind you that there are several resources available at the university to support you; I’ve posted several links on our course Canvas for your reference. So let’s take a moment to honor how we are feeling before we go into the day’s activities. Let’s take a deep breath. [pause]. Good. Thank you. [pause]. Last week, we. . .”

If your bandwidth for facilitating an activity and engaging with your students falls on the higher end of the spectrum, you could also give students 1-2 minutes to write how they are feeling on a piece of paper, and then invite them to put that piece of paper aside, as a symbol of their choosing to enter into the learning process with you.

A word of caution: Be cognizant of the power dynamics between you and your students and between each student and their peers. We advise against activities that ask students to share with the whole class—(even anonymously)—how they are feeling (word clouds, chat) about the election outcomes since their emotions will likely run the gamut from angry, to depressed, to elated, to relieved, and everything in between. More harm than good could be done to individual students and to the class environment as a whole as some students could feel threatened or jump to assumptions about other classmates based on their reading and interpretation of their peers’ feelings and emotions.

Quadrant B and C: Acknowledge + Refer + Activity

In addition to acknowledging and referring to campus resources (see above), your pedagogical and disciplinary proximity to the outcome of the election may compel you to engage with your students more substantially. If this is the case, we strongly encourage you to review the University of Michigan Center for Research in Learning and Teaching series “Preparing to Teach About the 2020 Election (and After)” to thoughtfully establish the most productive course of action in your classroom.

Closing Considerations

- Regardless of the quadrant you find yourself in, it’s a good idea to have a curated list of university resources to share with your students. You are welcome to use or adapt our own list for your context.

- When designing activities for engagement, keep two important things in mind:

- Avoid introducing new pedagogical strategies that may feel particularly vulnerable and may prove challenging to facilitate effectively – activities that could do more harm than good. For example, while you may want to have a discussion with your class, if you have not previously engaged in discussions on other topics with appropriate guidelines for participation and engagement, it would be best to instead design a writing assignment that gives students an opportunity to discuss their thoughts directly with you. You can identify common themes and contrast areas that emerge in the individual writing assignments and share those with your students at a subsequent class session.

-

- Assess your experience and capacity to prepare and facilitate the activity. If you are asking students to submit a writing assignment, it will be important to turn those around quickly and give students some form of feedback on your review of their responses. Do you have that workload and time capacity?

- Tyng, C. M., Amin, H. U., Saad, M., & Malik, A. S. (2017). The Influences of Emotion on Learning and Memory. Frontiers in psychology, 8, 1454. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01454 ↵

- Olsen, J. (2020, October 21). Teaching Around the Election: Flexibility, Acknowledgement, and Other Strategies [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://blogs.commons.georgetown.edu/cndls/2020/10/21/teaching-around-the-election-flexibility-acknowledgement-and-other-strategies/ ↵