Writing Is Recursive

Christopher Blankenship

In a recent interview, Steven Pinker, Harvard professor and author of The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century, was asked how he approaches the revision of his own writing. His answer? “Recursively and frequently.”

What does Pinker mean when he says “recursively,” though?

You’re probably familiar with the root of the word: “cursive.” It’s the style of writing that you may have been taught in elementary school or that you’ve seen in historical documents like the Declaration of Independence or Constitution.

“Cursive” comes from the Latin word currere, meaning “to run.” Combine this meaning with the English prefix “re-” (to do again), and you have some clues for the meaning of “recursive.”

In modern English, recursion is used to describe a process that loops or “runs again” until a task is complete. It’s a term often used in computer science to indicate a program or piece of code that continues to run until certain conditions are met, such as a variable determined by the user of the program. The program would continue counting upwards—running—until it came to that variable.

So, what does recursion have to do with writing?

You’ve probably heard writing teachers talk about the idea of the “ writing process” before. In a nutshell, although writing always ends with the creation of a “product,” the process that leads to that product determines how effective the writing will be. It’s why a carefully thought-out essay tends to be better than one that’s written the night before the due date. It’s also why college writing teachers often emphasize the idea of process in their classes in addition to evaluating final products.

There are many ways to think about the writing process, but here’s one that my students have said makes sense to them. It involves five separate ways of thinking about a writing task:

Invention: Coming up with ideas.

This can include thinking about what you want to accomplish with your writing, who will be reading your writing and how to adapt to them, the genre you are writing in, your position on a topic, what you know about a topic already, etc. Invention can be as formal as brainstorm activities like mind mapping and as informal as thinking about your writing task over breakfast.

Research: Finding new information.

Even if you’re not writing a research paper, you still generally have to figure out new things to complete a writing task. This can include the traditional reading of books, articles, and websites to find information to cite in a paper, but it can also include just reading up on a topic to learn more about it, interviewing an expert, looking at examples of the genre that you’re using to figure out what its characteristics are, taking careful notes on a text that you’re analyzing, or anything else that helps you to learn something important for your writing.

Drafting: Creating the text.

This is the part that we’re all familiar with: putting words down on paper, writing introductions and conclusions, and creating cohesive paragraphs and clear sentences. But, beyond the words themselves, drafting can also include shaping the medium for your writing, such as creating an e-portfolio where your writing will be displayed. Writing includes making design choices, such as formatting, font and color use, including and positioning images, and citing sources appropriately.

Revision: Literally, seeing the text again.

I’m talking about the big ideas here: looking over what you’ve created to see if you’ve accomplished your purpose, that you’ve effectively considered your audience, that your text is cohesive and coherent, and that it does the things that other texts in that genre do.

Editing: Looking at the surface level of the text.

Editing sometimes gets lumped in with revision (or replaces it entirely). I think it’s helpful to consider them as two separate ways of thinking about a text. Editing involves thinking about the clarity of word choice and sentence structure, noticing spelling and grammatical errors, making sure that source citations meet the requirements of your citation style, and other such issues. Even if editing isn’t big-concept like revision is, it’s still a very important way of thinking about a writing task.

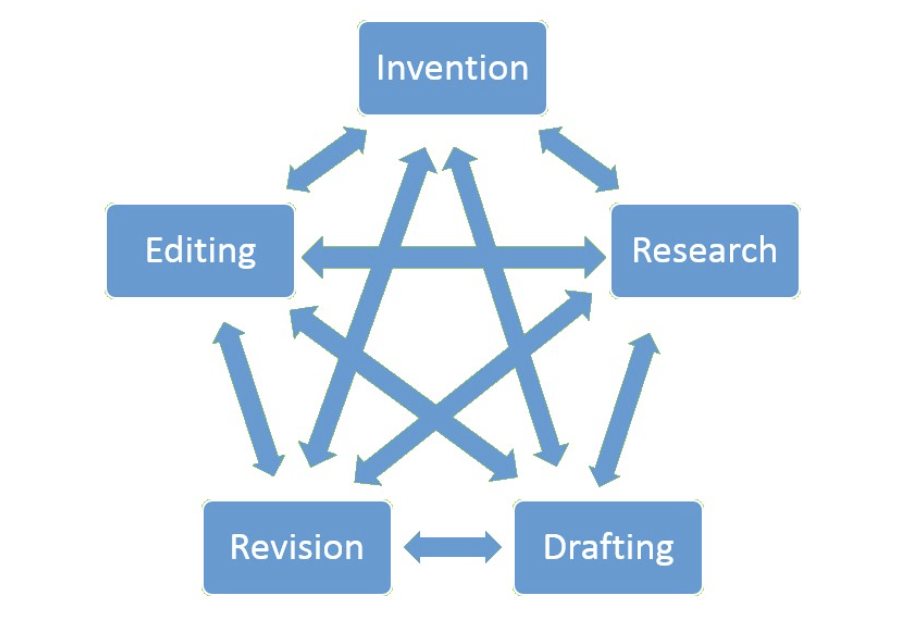

Now, you may be thinking, “Okay, that’s great and all, but it still doesn’t tell me what recursion has to do with writing.” Well, notice how I called these five ways of thinking rather than “steps” or “stages” of the writing process? That’s because of recursion.

In your previous writing experiences, you’ve probably thought about your writing in all of the ways listed above, even if you used different terms or organized the ideas differently. However, Nancy Sommers, a researcher in rhetoric and writing studies, has found[1] that student writers tend to think about the writing process in a simple, linear way that mimics speech:

This process starts with thinking about the writing task and then moves through each part in order until, after editing, you’re finished. Even if you don’t do this every time, I’m betting that this linear process is probably familiar to you, especially if you just graduated high school.

On the other hand, Sommers also researched how experienced writers approach a writing task. She found that their writing process is different from that of student writers:

Unlike student writers, professional writers, like Steven Pinker, don’t view each part of the writing process as a step to be visited just once in a particular order. Yes, they generally begin with invention and end with editing, but they view each part of the process as a valuable way of thinking that can be revisited again and again until they are confident that the product effectively meets their goals.

For example, a colleague and I wrote a chapter for a book on working conditions at colleges, a topic we’re interested in.

- When we started, we had to come up with an idea for the text by talking through our experiences and deciding on a purpose for the text. [Invention]

- Although we both knew something about the topic already, we read articles and talked to experts to learn more about it. [Research]

- From that research, we decided that our original idea didn’t quite fit with the research that was out there already, so we made some changes to the big idea. [Invention]

- After that, we sat down and, over several sessions on different days, created a draft of our text. [Drafting]

- When we read through the text, we discovered that the order of the information didn’t make as much sense as we had first thought, so we moved around some paragraphs, making changes to those paragraphs to help the flow of the new order. [Revision]

- After that, we sent the rough draft to the editors of the book for feedback. When we got the chapter back, the editors commented that our topic didn’t quite fit the theme of the book, so, using that feedback, we changed the focus of the ideas. [Invention]

- Then we changed the text to reflect those new ideas. [Revision]

- We also got feedback from peer reviewers who pointed out that one part of the text was a little confusing, so we had to learn more about the ideas in that section. [Research]

- We changed the text to reflect that new understanding. [Revision and Editing]

- After the editors were satisfied with those revisions, we proofread the article and sent it off for final approval. [Editing]

In this process, we produced three distinct drafts, but each of those drafts represents several different ways that we made changes, small and large, to the text to better craft it for our audience, purpose, and context.

One goal of required college writing courses is to help you move from the mindset of the student writer to that of the experienced writer. Revisiting the big ideas of a writing task can be tough. Cutting several paragraphs because you find that they don’t meet the purpose of the writing task, throwing out research sources and having to search for more, completely reorganizing a text, or even reconsidering the genre can be a lot of work. But if you’re willing to put aside the linear steps and view invention, research, drafting, revision, and editing as ways of thinking that can be revisited over and over again until you accomplish your goal, you will become a more successful writer.

Although your future professors, bosses, co-workers, clients, and patients may only see the final product, mastering a complex, recursive writing process will help you to create effective texts for any situation you encounter.

- Revision Strategies of Student Writers and Experienced Adult Writers” in College Composition and Communication 31.4, 378-88. ↵