Universal Design for Learning

Three Principles of Universal Design for Learning

Where Universal Design anticipates people’s diverse ways of being through the design of physical spaces and objects, Universal Design for Learning (UDL) anticipates diverse ways of being through the design of education policy, curriculum, instruction, and assessment.

The fight for disability rights is ongoing and crucial to any institution’s progress toward equity in education. The UDL framework helps instructors and administrators recognize the many ways in which standard policies and “best” practices exclude people with disabilities, and it provides flexible, non-prescriptive guidelines for revising those policies and practices with inclusivity in mind.

There are many excellent online resources that provide introductions and practical applications of the UDL framework in higher education (you can find links to a few such resources under References & Further Reading below). One resource of particular utility for orienting oneself to the major principles of UDL is the UDL GuidelinesLinks to an external site., developed by CAST.

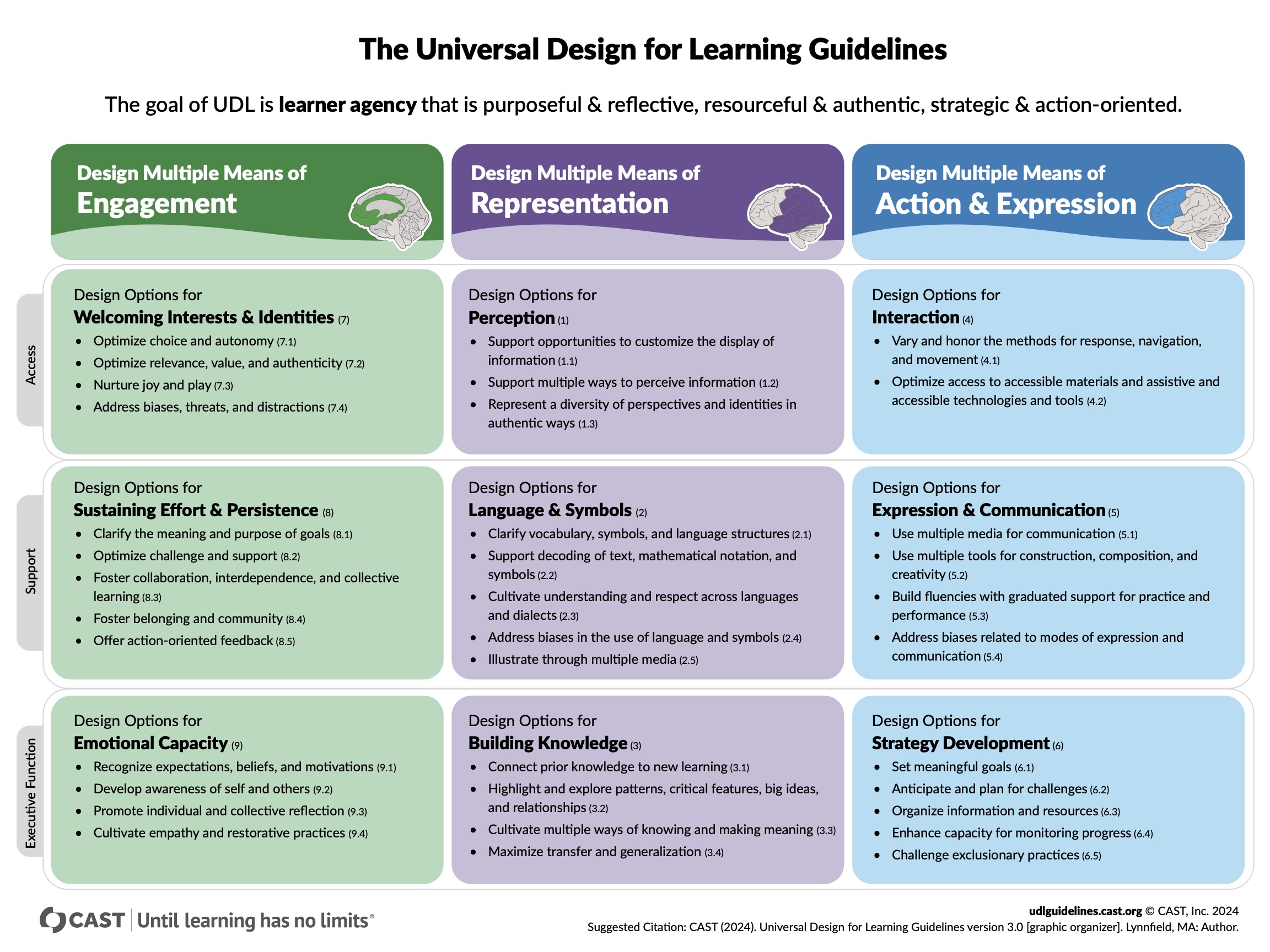

These guidelines are grounded in cross-disciplinary researchLinks to an external site. and present three main principles to keep in mind as you incorporate the UDL framework in your teaching and course design:

- Multiple means of representation

- Multiple means of engagement

- Multiple means of action & expression

These principles aren’t necessarily intuitive, so let’s unpack each one a little further.

Multiple Means of Representation

Within this principle, instructors strive to create multiple pathways for learners to acquire information and to build knowledge (or, as CAST frames it, the “what” of learning). This means, among other things, that students will have opportunities to engage with course content through text (reading), audio (listening), and visuals (viewing/watching graphics, symbols, and animations).

This principle also encourages instructors to be mindful in their selection of illustrative examples of course concepts. For instance, examples or scenarios routinely grounded in able-bodied (or white, or American, etc.) experience can and do present barriers to learning for students whose lived experiences do not intersect with the socio-cultural parameters of the example/scenario.

Multiple Means of Engagement

This principle taps into the internal or affective dimensions of learning (what CAST presents as the “why” of learning). Instructors following this principle will present students with several avenues to connect with course material, tap into personal motivations, and build persistence.

One common way instructors provide multiple means of engagement is by building in elements of choice and autonomy in course assignments. For instance, encouraging students to pursue a research or writing project that is of personal interest to them can sustain motivation and deepen learning.

Multiple Means of Action/Expression

This principle (framed by CAST as the “how” of learning) reminds instructors to provide their students options in how they can demonstrate their learning. This means that students might be challenged to verbalize their understanding of course concepts through various forms of speech and writing (e.g. low- and high-stakes presentations, discussion posts, formal writing assignments), or to illustrate their understanding through other means (e.g. demonstrations, diagrams, concept maps).

- Jay Dolmage’s monograph on the systematic exclusion of people with disabilities in higher education (link opens in separate tab): Academic Ableism: Disability and Higher EducationLinks to an external site..

- Jay Dolmage’s article in Disability Studies Quarterly (link opens in separate tab): “Universal Design: Places to StartLinks to an external site.“

- CAST’s website dedicated to UDL in higher education (link opens in separate tab): http://udloncampus.cast.org/homeLinks to an external site.

- CAST’s introductory website to UDL (link opens in separate tab): http://udlguidelines.cast.orgLinks to an external site.