XI. Supporting Students in the Writing Process: Language Diversity and Multilingual Writers

Marking (or NOT Marking) Errors

Commenting on surface-level grammar errors can have negative impacts on both students and instructors. Research has shown, for instance, that receiving papers with many grammar corrections doesn’t necessarily help students to understand grammar or prevent them from making the same mistake in the future. Worse, receiving papers with many grammar corrections can lead to students:

- feeling judged

- using limited sentence structure and vocabulary (i.e., playing it “safe”)

- losing a sense of self-efficacy in English language and in academics more generally

For instructors, time spent on (needlessly and sometimes harmfully) marking grammar errors takes away from time dedicated to the more important work of responding to content and ideas. Instructors should prioritize responding to the content that is being assessed in a writing assignment over considering any grammatical errors.

Considerations for when and what to mark about grammar errors

Stage of the writing process

First drafts: If students will have an opportunity to correct their errors for the next draft, consider what errors will be rendered moot through revision and refrain from marking or commenting on them.

Final drafts: If students won’t have an opportunity to correct their errors, consider the purpose of marking corrections (keeping in mind that having an error marked does not necessarily help the student understand how not to reproduce the error in the future).

Subjectivity of “errors”

There’s not always a clear line between objective and subjective grammar errors. Consider the degree to which your own subjective preferences for words, phrases, and sentence structures affect what you want to mark. (Many of us are overly concerned with the grammar and style issues we’ve gotten feedback on in our own writing!)

Another consideration: Just as all speakers have accented speech, and you wouldn’t want to “correct” someone’s pronunciation just because it is reflective of a different version of English from your own, consider grammar issues that are not objectively wrong and don’t affect meaning as accented writing. “Accented writing” refers to writing that indicates something about the writer’s linguistic background. In our work with students, it can be productive to accept (and even appreciate) that they may use wording or grammar reflective of their unique linguistic background.

Frequency and patterns of errors

Consider marking only errors that follow a consistent pattern (e.g., many instances of singular nouns when they should be plural) and that occur repeatedly. This could look like an overall comment such as, “you have many errors with plurals, and I’ve highlighted these errors in yellow”, and then highlighting all the nouns with issues with plurality).

You might choose to ignore errors that occur once or twice because this is unlikely to lead to a learning experience for the student.

Impact of errors

Consider only marking errors that impact your understanding of content.

Context of Writing Task

Use the context of the writing task to guide how you respond to errors in a student’s work. The way you approach marking errors on, for example, a paper that assesses students’ understanding of course materials should be different from the way you might approach marking errors on an NSF grant proposal that’s due in less than 24 hours.

Examples of Marking and Giving Feedback to Student Work

These examples will show the same student text, which was written by a first semester master’s student in Economic Policy, with a variety of feedback strategies.

The Student Text

Introduction

Female plays a big role in improving countries economic growth due to her strong participation in any sectors. According to Klasen countries who have discrimination between male and female are experiencing low economic growth than the others who do not (1999). Saudi Arabia one of the biggest oil producers in the world, and it has low women labor force participation in the world. Based on General Saudi Arabia Authority for statistics, women who are participating in the labor force only 15% of the population, which is very low comparing to men who are around 76%.

Women in Saudi Arabia have shown a lot of improvement regarding their qualification. For example, Thoraya Obaid the first female who is working as a head of United Nations agency, and Dr. Hayat Sindi the first Saudi women who developed the point of care medical testing and biotechnology. [ . . . ]

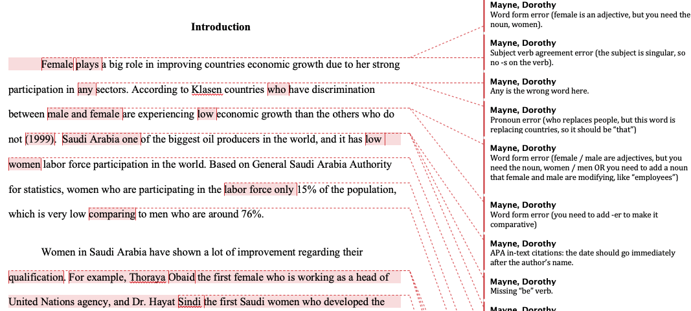

Example 1: Identifying, naming, and instructing about errors

In this example, the instructor identifies each grammar error by indicating what kind of error it is and providing a brief comment about how to fix it.

This type of feedback could help the student learn to make most corrections on their own, and there is some instruction that the student could take away from the comments that could help prevent them from making the same error again. However, research on the effectiveness of this kind of grammar correction on student writing has inconsistent findings. Also, while there is quite a lot of feedback here, it is ONLY about local (i.e., sentence-specific) concerns, potentially overwhelming the student with a lot of feedback, none of which responds to the intellectual work of the paper. This takes a lot of time and effort on the part of the instructor, and there is little evidence that it helps students and some evidence that it is harmful to students.

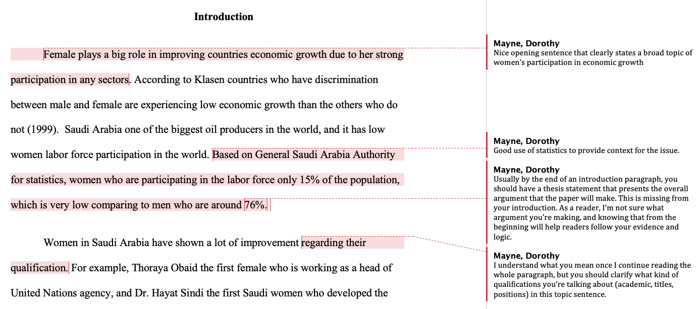

Example 2: Ignoring all grammar errors and responding to the content

This type of feedback ignores the presence of any grammar errors (none of which caused an issue with understanding the content) and instead addresses the content of the paper and what the assignment is meant to assess. The example feedback is based around assessing the paper’s organization. If the purpose of the assignment were to assess students’ ability to use statistics to make an argument, to understand economic growth, or something else, this feedback could be entirely different. Global feedback should address the purpose of a writing assignment as a priority over anything else.

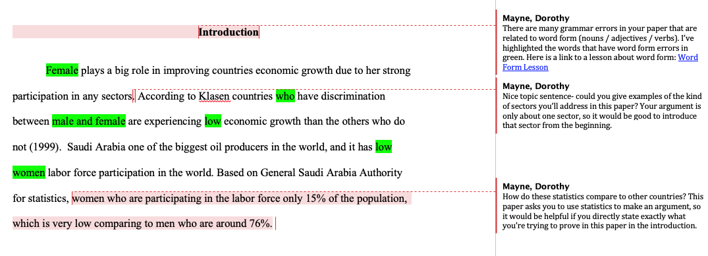

Example 3: Responding to the content while pointing out consist patterns of grammar errors

First, this example shows what it can look like to select one specific grammar issue (word form) and highlight all instances of that error. Word form errors were the most common in this paper, and they arguably had the most potential to disrupt meaning. Not only are word form errors highlighted, but there’s also a general comment about it, including a link to a lesson about this topic. This strategy isn’t always useful or possible. You may not be able to identify the kinds of errors, and you may even wrongly identify kinds of errors, potentially confusing students. In fact, “word form” as a category of error is vague. It’s great to point students to resources that are related to the pattern of error you identified, but not all online lessons are effective for the level of your students, and in many cases, finding a lesson that is applicable and helpful could be very time consuming. The Writing Center has many resources for lessons and practice with English language conventions that are designed specifically for UW students. For the global comments about content, this feedback is imagined as if the instructor is assessing the students’ ability to use statistics to make an argument, so all global comments are related to that issue.

There’s no one, right way to give grammar feedback. The kind of feedback that you should give (if any at all) will depend on many factors, including the purpose of the assignment, your knowledge of grammar, your time, and much more. There are different approaches with benefits and drawbacks, and each student has individual-level and ever-changing factors that will determine what kind of feedback is helpful and harmful to them.

Further reading on marking grammar errors

Ferris, Dana and Roberts, Barrie. “Error Feedback in L2 Writing Classes: How Explicit Does It Need to Be?” Journal of Second Language Writing, 10 (2001): 161-184.

Ferris, Dana. “The ‘Grammar Correction’ Debate in L2 Writing.” Journal of Second Language Writing, 13.1 (2004): 49–62.

-

- In the field of Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language, these articles are considered seminal publications on this topic. The authors provide an overview of research on grammar error correction, implications for future research, and implications for practice. Ferris has continued to focus on this question throughout her career, highlighting how inconsistent research on the effectiveness of grammar correction can be. Often it’s found to be ineffective, but that varies depending on context, course content and purpose, and more.

Boggs, Jull. “Effects of Teacher-Scaffolded and Self-Scaffolded Corrective Feedback Compared to Direct Corrective Feedback on Grammatical Accuracy in English L2 Writing.” Journal of Second Language Writing, 46 (2019).

-

- Through this quantitative quasi-experimental study, the author found that the quality and detail of written grammar feedback did not predict increased grammatical accuracy, highlighting that grammar corrections were not effective in helping students prevent reoccurance of the grammar error that is marked and given feedback.

Mao, Shiman Shae and Crosthwaite, Peter. “Investigating Written Corrective Feedback: (Mis)alignment of Teachers’ Beliefs and Practice.” Journal of Second Language Writing, 45 (2019): 46-60.

-

- This study investigates the misalignment teachers’ perceptions of their written corrective feedback and their actual written corrective feedback. Teachers believed that they responded mostly to global issues in students’ writing, but an analysis of their feedback showed that they commented on local issues more frequently. Thus, there can be a disconnect between what instructors believe about providing corrective feedback and what they actually do in practice.