VIII. Providing Feedback on (and Evaluation of) Student Writing

Strategies for Responding to Student Writing

Carefully consider how you respond to and evaluate your students’ writing. As Adam Rosenblatt has stated, “Traditional grading is one of the academy’s most pervasive and unquestioned forms of structural injustice.” Research has shown that the feedback they receive on writing can influence a student’s sense of self and wellbeing as well as their educational outcomes.

In addition to adopting a mindset that prioritizes students’ growth as critical thinkers and writers, develop a strategy for providing timely, effective feedback to students. We suggest several such strategies below, and we recommend that you experiment with different combinations to find an approach that feels comfortable within your specific teaching context. (Remember, too, that some assignments—like low-stakes writing activities—may not require extensive feedback!)

Write a Headnote or Endnote

You might think of this as a brief letter to the student in which you help them identify what areas or aspects of the assignment should take priority in their efforts toward revision. By speaking to your students directly through this personalized form, you also gain the opportunity to build rapport with them (more importantly trust, and most importantly a sense of belonging).

Balance praise and constructive criticism

Educational specialists advise that feedback should strike a balance between praise and critique / suggestions for improvement. One way to ensure you are offering praise in addition to critique is to use the “Rose, Bud, Thorn” method of crafting a headnote.[1] Following this method ensures that you offer praise, critique, and suggestions for future improvement. In your feedback to students, consider including at least one statement from each of the three categories.

| ROSE | BUD | THORN |

| Point out something that is already a point of strength.

Maybe the student has a very interesting topic, or they have a lot of great evidence from peer-reviewed sources. |

Point out something with potential.

Maybe it’s a subpoint that could be developed more or a term that needs further explaining. |

Point out something that needs significant improvement.

Maybe the syntax is overly complex, or the diction/idiom is not quite right, and meaning is frequently obscured. |

Examples

Consider how the following two examples employ the Rose-Bud-Thorn method. How might you adapt either of these approaches to feel more genuinely in conversation with your students?

Example 1

Hi [Student],

Thanks for sharing your writing with me! Your transition sentences do an excellent job of pointing to your topic changes and of outlining the overall structure of your paper. You also do a great job of effectively introducing and explaining your sources. In your revision, you’ll need to go a step further and analyze how the sources connect to each other to show your understanding of this body of scholarship. Finally, sometimes it’s unclear what your pronouns refer to (for example, “this” at the bottom of p. 3 was confusing). Try using concrete nouns to signify what “this” means.

Example 2

[Student Name],

Some good details here from the experiments—that’s really important in a summary. As you revise, focus on content, organization, and clarity. Here are some key next steps:

- How can you give your readers a fuller picture of the overall purpose of the research before launching into the details of the first experiment?

- After that overview, then devote one paragraph to each experiment

- Give more space to the most important findings and explain their significance.

- After working on these larger concerns, then be sure to proofread and edit carefully—there’s a sentence in the last paragraph that’s confusing, and throughout there are a number of problems with word choice and punctuation.

Glad to meet to talk about any of this feedback and glad to help as you revise. I’m looking forward to reading your next draft.

– [Instructor Name]

Prioritize Global Concerns over Local Ones

In your responses to students, prioritize large-scale, “global” issues (i.e. quality of ideas, arguments, experimental or research design, depth of analysis, findings, use of evidence, focus, clarity of main idea, development of ideas, logic, understanding of course concepts, etc.) over “local” issues such as spelling mistakes, minor grammatical errors, or other issues that don’t significantly interrupt the logical flow. See this chapter from Bean and Melzer for more specific suggestions (available through UW-Madison libraries).

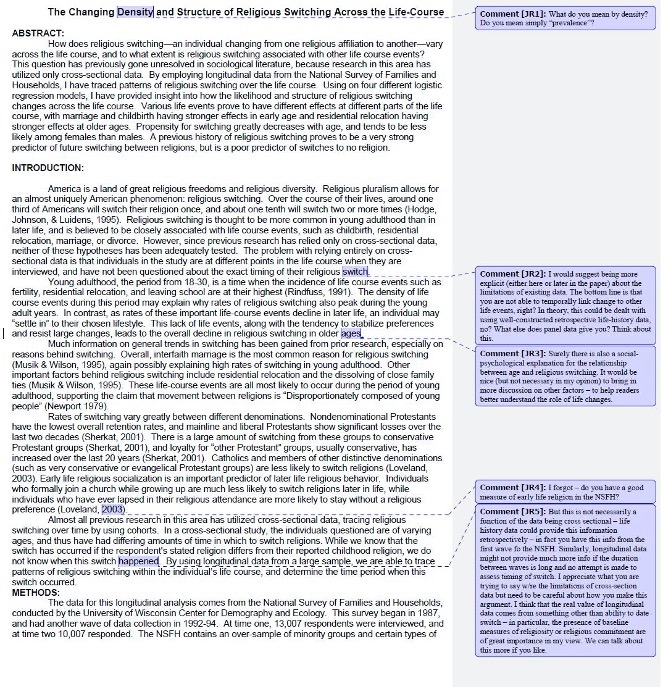

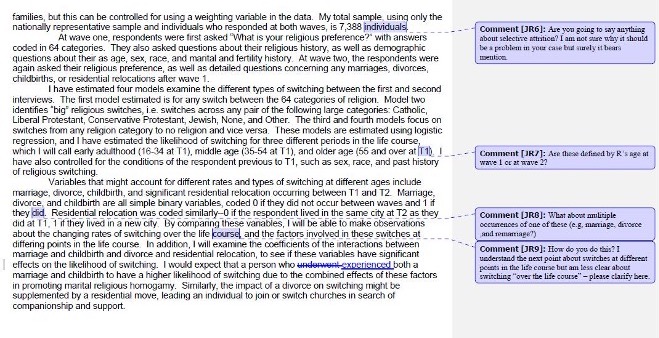

Comment in the Margins

Marginal comments—whether typed using the Commenting feature of MS Word or Google Docs or handwritten—allow you to target feedback to very specific moments within students’ drafts. Note how, in the example below, Professor Jim Raymo uses marginal comments to engage with the substance of his student’s research. He effectively uses a combination of questions and suggestions to guide and deepen thinking. Note, too, how he effectively blends encouragement with criticism and advice, and invites the student to speak with him further about some of his suggestions.

Using Alternatives to Written Feedback

In person meeting

Occasionally, you may find that a particular assignment or individual student draft doesn’t lend itself well to the strategies we’ve outlined here. For instance:

- If student’s draft is really in trouble and you’re not sure where to start with your feedback, have a conversation with the student (in person or virtually) rather than respond in writing. This creates opportunity for you to learn about the student’s circumstances or challenges, and allows the student to learn more about your expectations.

- If you’re finding a common problem across many papers for the same assignment, don’t respond to all of them—address and teach about that common problem in class. Next time you plan to use that assignment, consider revising it for clarity or incorporating pre-emptive instruction in your course curriculum.

Group feedback

Sometimes instructors find themselves writing the same comments on almost every student paper. If this is the case, you may want to give the class some collective feedback about the most common problems you find in their papers, eliminating the need for detailed explanation on each student’s paper. Here’s an example of one professor’s collective comments to students in an introductory English class:

Dear Class,

I wanted to give you some collective feedback about this first paper, in addition to the more personalized notes I’ve left on each response sheet. Overall, I truly enjoyed reading these papers; most showed evidence of careful thought and hard work. I appreciate that. However, there were some errors common to many papers, and some comments that I found myself writing over and over again, so I thought it might be useful to address them here.

Description vs. Analysis:

Many of you had the right instinct and cited the text in your papers—a fine beginning! However, telling your reader what is there in your poem (just describing it) takes the reader only half-way; continue by teasing out the how and why questions (questions of significance). Also, especially with poetry (but also with prose), it’s often useful to ponder the precise language that the author employs—consider these detailed, technical matters and pose a theory of their significance for your reader.

Documentation:

You underline books, like Songs of Innocence, and quote poems, like “Holy Thursday.” Also, after a quote from a poem, identify it with a line number (not a page number) in parentheses.

Its vs. It’s:

If you want to write the contraction for “it is” then use “it’s.” For example: It’s about time we were leaving. If you want to write about something that belongs to “it” then use “its.” For example, My dog could chase its tail all day long.

I hope you’ll keep these tips in mind next time you sit down to work on a paper—for this (or any other) class.

Thanks for all your effort!

And if you have any questions at all—about comments, grades, the poems themselves, etc., I STRONGLY ENCOURAGE you to come in and chat. If my office hours aren’t convenient, I’m happy to make an appointment.

Audiofeedback

Some students may benefit from receiving audio feedback on their written work. In addition, for some instructors, providing audio feedback can serve as a welcome change from writing feedback. See this article and this one for suggestions on giving audio feedback. Audiofeedback introduces your voice into your feedback, so rather than a paper with red marks, students get to hear directly from you. They get to hear your encouragement, your inflection points, and your warmth.

Screencast feedback

A screencast is a recording that captures actions on a computer screen and can be accompanied by your voice. It is an innovative way to deliver clear feedback to a student writer by allowing them to follow along with you as you comment on their work. Through screencast evaluation, you can indicate specific revision needs, offer suggestions for following through on revision, talk through how you graded the assignment on your rubric, and more.

When teaching online, it may be challenging to feel a personal connection with your students, and your students may feel the same way. Like audio feedback, a screencast allows students to hear your voice and to see specifically where in the draft you had praise and/or suggestions or critiques. You can learn more about screencasting here and here.

- Our gratitude to UW-Madison Sociology TA Abby Letak for sharing this strategy. ↵