Strategies for Effective Assignment Design

As students progress through their degree programs, it becomes increasingly important for them to learn the major genres, research strategies, and writing conventions of their field. Because writing expectations vary across disciplinary and professional contexts, students benefit from transparent explanation of what those expectations are, how to achieve them, and why they’re important. This can be accomplished through carefully designed formal assignments.

Experts in Writing across the Curriculum argue that students learn most successfully when formal assignments engage them with “authentic research projects that promote disciplinary ways of inquiry and argument and are written in real disciplinary genres.[1] from the National Survey of Student Engagement shows that deep learning depends less on the amount of writing assigned in a course than on the design of the writing assignments themselves. According to this and other research, effective assignments have the following three features:[2] a meaning-constructing task, clear explanations of expectations, and interactive components.

-

Engage students in meaning-making

A meaning-constructing task asks students to bring their own critical thinking to bear on problems that matter to both the writer and the intended audience. A meaning-constructing task typically presents students with a disciplinary problem, asks them to formulate their own problems, or otherwise engages them in active critical thinking in a specific rhetorical context.

-

Provide clear expectations

Effective assignments clearly present the instructor’s expectations for a successful performance. Ideally, the assignment prompt also explains the purpose of the assignment in terms of the course’s learning goals and presents the instructor’s evaluation criteria.

-

Include interactive components

Interactive activities situate writing as a process of inquiry and discovery, promote productive talk about the writer’s emerging ideas, and encourage multiple drafts and global revision.

Create a Rhetorical Context

Creating a rhetorical context for your assignments means considering the role students will play in their writing, the audience they are meant to address, the format (or genre) of the writing task, and the task they are meant to accomplish. The mnemonic RAFT is helpful to recall these four components.[3]

-

Role

Having a role helps students understand the kind of change they hope to bring about in their audience’s view of the subject matter. Without a specific role to play other than “student,” writers in your class might assume that their purpose is simply to regurgitate information to the instructor.

-

Audience

Specifying an audience goes hand-in-hand with establishing the student’s role. By identifying an audience, the instructor can help students see how their writing might influence a reader’s stance.

-

Format/Genre

By specifying a genre (e.g., experimental report, op-ed piece, proposal), the assignment helps students transfer earlier genre knowledge to the current task and make decisions about document design, organization, and style. It also helps instructors clarify expectations about length, citation style, etc. More important still, the rhetorical awareness enabled by writing in a specific genre also creates an awareness of a discourse community at work. To students, college writing assignments often appear to be an isolated transaction between student and teacher. Students assume that strange features of the assignment reflect the idiosyncrasies of the instructor rather than the conventions of a larger community. When instructors assign authentic genres there is an opportunity to make discourse community values and expectations explicit.

-

Task (Problem-Focused)

The task itself sets forth the subject matter of the assignment. Unlike topic-focused tasks (e.g., research/write about X), which can lead to unfocused papers that merely report information, a truly engaging task is typically embedded in disciplinary “problems” and disciplinary ways of thinking and argumentation. A problem-focused task should give students agency to bring their own critical thinking to bear on the subject matter—that is, to engage them in making their own meaning.

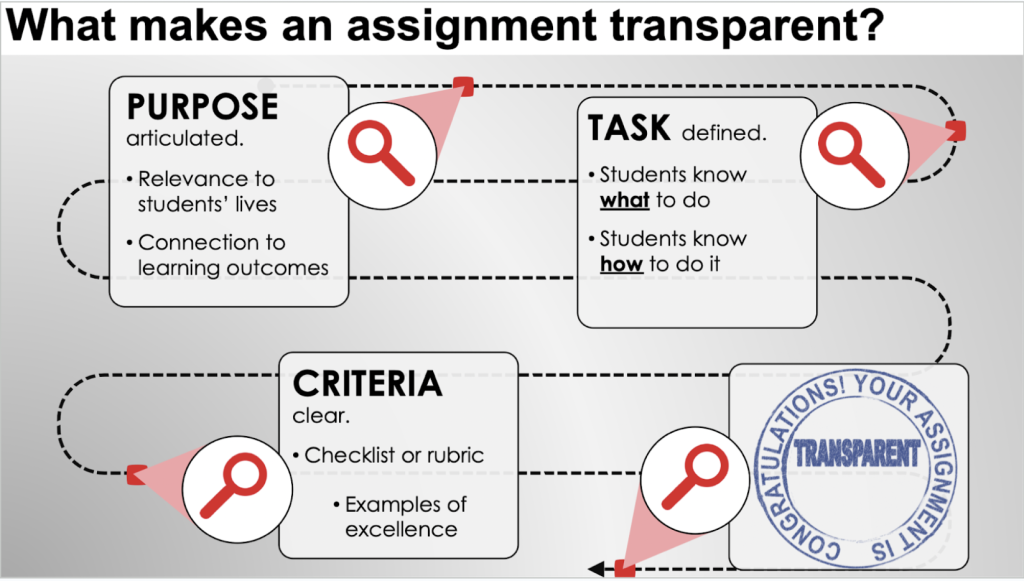

Use Transparent Assignment Design

Often an assignment that seems clear to you can be confusing to your students. While designing your assignments, ask yourself what might be unclear to your students—what assumptions might you be making about their procedural or background knowledge? Scholar Mary Ann Winkelmas

-

Align writing activities and assignments clearly with learning objectives

-

The goal of Transparent Assignment Design is to “to make learning processes explicit and equally accessible for all students” (Winkelmes et al., 2019, p. 1).

-

Make clear the purpose, task, and criteria for success.

-

For more information visit TILT (Transparency in Teaching and Learning)

Example: Less Transparent

Assignment from an Introductory Communications Course

1. Select a professional in your prospective academic discipline and/or career filed that is considered an expert in an area in which you are interested

2. Secure an interview with the professional for a date and time that is convenient for both of you.

3. Prepare 8-10 questions to ask the professional about their knowledge of a particular academic discipline/career field.

4. Conduct a 20-30 minute, face-to-face interview to gather knowledge that will help you make an informed decision about the major/career you are considering. You will want to audio/video record the interview with the interviewee’s permission

5. Prepare a typed transcript of the questions and answers using the audio/ video recording

6. Write a 400-500 word reflection paper in which you address the following items: a. Who you selected and why?

b. What you learned from them that is most interesting?

c. What this assignment helped you learn about your major/career decision?

7. What questions you still have?

8. Submit the typed transcript and reflection paper to your instructor

Revised EXAMPLE: More Transparent

Communications 100E, Interview Assignment

Used by permission of Katharine Johnson, University of Nevada, Las Vegas

Due dates:

- Sept 30 - Draft interview questions

- October 15 - Transcript of interviews - November 17 - Report

Purpose: The purpose of this assignment is to help you make an informed decision about the major/career you are considering.

Skills: This assignment will help you practice the following skills that are essential to your success in school and professional life:

- Accessing and collecting information from appropriate primary and secondary sources

- Synthesizing information to develop informed views

- Composing a well-organized, clear, concise report to expand your knowledge on a subject in your major.

Knowledge: This assignment will also help you to become familiar with the following important content knowledge in this discipline:

- Issues facing professionals in a field

- Scholarly research formats for documenting sources and creating reference pages (i.e.,

bibliographies).

Task: To complete this assignment you should:

1. Secure an interview with two professionals in hour prospective academic discipline

and/or career field who are considered experts.

2. Schedule the interviews with the professionals at a date and time that is convenient for

both of you.

3. Prepare 8-10 questions to ask the professionals about their expertise in a particular

academic or career field. The questions must be based on a review of the filed using 5 credible sources as defined by the librarian in our research module. Sources should be cited using APA formatting.

4. Conduct a 2 -3 -minute, face-to-face interview with each professional to gather knowledge that will help you make an informed decision about the major/career you are considering. You will want to audio/video record the interview with the interviewee’s permission.

5. Prepare a typed transcript of the interviews

6. Compare and contrast the information provided by both professionals in an 8-page (1.5

spaced, 12point Times New Roman font, 1 inch margins) report that documents the advantages and disadvantages of a career in the selected field.

Criteria for success: Please see the attached rubric.Type your textbox content here.

Information Literacy Skills Needed for Research Writing

Asking students to engage authentic, discipline-specific problems requires a kind of dismantling of the commonly encountered “research paper” culture in which students think of research as going to the library to find sources that can be summarized, paraphrased, and quoted. To move from “research paper” culture to a culture in which research projects are written in disciplinary genres, instructors need to help students develop the following skills related to information literacy:[4]

| How to ask discipline-appropriate research questions. | The nature of questions differs across disciplines, and fields are often divided by theoretical or methodological differences that affect the way questions are framed. Instructors must model for students how to develop their own questions that are discipline-appropriate, significant, and pursuable at their level of study. |

| How to establish a rhetorical context. | Writers write to an audience for a purpose within a genre. Instructors should consider building these parameters into their assignments. |

| How to find sources. | Students need to develop more sophisticated search strategies, as well as more sophisticated means of evaluating sources. Consider collaborating with a librarian. |

| Why to find sources. | Students need to learn that sources are not primarily for long quotations, but for specific purposes that help the researcher to create and share new knowledge. The mnemonic BEAM[5] helps to elucidate these different purposes: to serve as a Background source, as an Exhibit (or evidence derived from an exhibit), as a source of Argument or counter-argument, and as a source of Method |

| How to incorporate sources into one’s own writing. | Students need to learn to use sources purposefully within arguments, and learn when to quote, paraphrase, summarize, or reference. |

| How to take thoughtful notes. | Active note-taking enables critical thinking—something downloading PDFs does not do! Students need to learn that taking notes can help them determine the function of a source, summarize an argument in their own words, and record their own ideas. |

| How to cite and document sources. | Formatting citations is lowest in the hierarchy of skills, but of highest concern to students because they think teachers emphasize it most. |

Click "next" in the bottom right corner to continue reading this chapter.

- Bean, John C. and Dan Melzer. Engaging Ideas: The Professor's Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom. Jossey-Bass. Hoboken: 2021. p. 218[footnote]” So, an effective formal assignment identifies the many components that contribute to a polished final product, explaining what research and writing practices are conventional in the field and to that specific genre. Ideally, students will have opportunities for feedback and revision along the way.

Consider the Novice-Expert Framework

Consider where the students in your class might fall on a continuum from "outsider" to "insider" within your discipline, or from novice to expert writer. Compare where you would expect students to fall if they were enrolled in a first-year interest group (FIG) course, an upper-level course, or a graduate seminar. (MacDonald’s schema, provided in Table 2 below, provides a helpful developmental model to guide your reflection.) Use these considerations to guide your selection of what research projects and writing genres you might assign across your teaching.Stage Kinds of Research Writing Hypothetical Curriculum Nonacademic writing Writing a report about ___________ K-12 Generalized academic Stating claims, respecting others’ opinions, offering evidence, writing with authority First-year composition Novice approximations of disciplinary ways of making meaning Students are beginning to learn a new discipline, beginning to approximate kinds of writing Upper-division courses Expert, insider prose Students have become acculturated into a new discipline Graduate study and some capstone-level courses Consider backward design

Whether you design research and writing assignments as formative or summative assessments, do your best to align them with your course goals. If you are asking students to complete a written assignment, carefully consider the purpose that their writing will serve: Will students be writing as a way of comprehending or applying complex concepts? Will students be writing as a way of demonstrating their mastery of disciplinary/professional communication? Some combination?Strategies for Effective Assignment Design

Research[footnote]Anderson, Paul; Anson, Chris M.; Gonyea, Robert M.; and Charles Paine. “How To Create High-Impact Writing Assignments That Enhance Learning and Development and Reinvigorate WAC/WID Programs: What Almost 72,000 Undergraduates Taught Us.” Across the Disciplines, 2016, Vol.13 (4), p.1-18. DOI: 10.37514/ATD-J.2016.13.4.13 ↵ - Bean and Melzer, p. 64-65 ↵

- All of this section excerpted and paraphrased from Bean and Melzer, pp. 66-68 ↵

- All of this section excerpted and paraphrased from Bean and Melzer, pp. 200-202 ↵

- Bizup, Joseph. “BEAM: A Rhetorical Vocabulary for Teaching Research-Based Writing.” Rhetoric Review, 2008, Vol.27 (1), p.72-86. DOI: 10.1080/07350190701738858 ↵