V. High-Stakes, Formal Writing Assignments

Why incorporate high-stakes writing into your teaching?

Incorporating high-stakes writing assignments in your teaching can offer students the opportunity to demonstrate their learning and to practice critical self-evaluation. High-stakes writing can give an instructor ways to assess student learning in their course, provide information about the effectiveness of their teaching, and foster student-instructor and student-student connections.

1. High-stakes writing can help students grow as writers and thinkers by:

Fostering critical thinking. Research across disciplines demonstrates that writing and thinking are linked in powerful ways. Writing is a cognitive, as well as communicative, act. Writing involves, for example:

- Retrieving prior knowledge

- Connecting to new knowledge

- Generating complex understanding

- Motivating deeper learning

- Building persistence

- Growth mindset

As John Warner writes in “Writing is Thinking” (2023): “Writing is simultaneously the expression and the exploration of an idea. As we write, we are trying to capture an idea on the page, but in the act of that attempted capture, it’s likely (and even desirable) that the idea will change.”

Giving the opportunity for feedback and revision. Giving students the opportunity to get feedback from you as the instructor or from peers—and, just as importantly, to offer feedback to their peers—can get students closer to meeting learning goals. Feedback and revision are key parts of an effective writing process:

When we comment on papers, we should play the role of a coach providing guidance for revision, because it is through revising that our students learn most deeply what they want to say and what their readers need for ease of comprehension. Revising doesn’t mean just editing; it means “revisioning”—rethinking, reconceptualizing, “seeing again.” It is through the hard work of revising that students learn how experienced writers really compose. (Melzer & Bean, 2021)

Combining feedback from the instructor and peers can foster deep learning and reflection. Further, peer review has the added benefit of giving students the opportunity to encounter other students’ writing.

Promoting metacognition and learning transfer. High-stakes writing offers opportunities for reflection and growth when students engage in metacognition. Metacognition refers to the ability to think about and reflect on one’s own learning and thinking process. Students can be encouraged to reflect on the writing process before, during, and after writing a high-stakes assignment:

| Stage of the writing process | Questions to encourage metacognition |

| Before writing: students can reflect on goals | What do I want to accomplish in this paper?

How do I plan to navigate this assignment? How do I want to use/not use AI intentionally? |

| During writing: students can assess progress | What is the best thing about my draft so far?

Where am I stuck right now? What is affecting my writing process? |

| After writing: students can reflect on how it went | If I had more time, what would I change or add?

How has this changed from earlier drafts? What challenges arose in the process? Am I proud of this paper? |

For more on reflective writing, see Boston University’s (2023) website on “Reflective Writing Activities.”

2. High-stakes writing can promote learning and disciplinary knowledge by:

Offering opportunities to learn about different disciplinary genres. “Genre” refers to the conventional combination of format, organization, purpose, and audience for specific types of writing—like how we know that a resume should have the applicant’s name in large font towards the top and include various section headings. Students aren’t just writing “papers” in their coursework—they are actually writing different genres in each class, and sometimes multiple genres within a single class. Whether it is the subtle difference of a close reading or a critical analysis in different literature classes, or larger differences among writing business proposals, lab reports, and press releases, each genre that students encounter will have different expectations.

Writing in authentic disciplinary genres (such as a lab report in biology or an op-ed in public health) helps students learn more deeply about the discipline itself, and disciplinary ways of knowing and telling. Having students write in genres that they will use outside of the university will help them prepare for specific writing scenarios they might encounter, but it also helps apprentice students into the field of study (Carter et al., 2007). Students learn more how to think like a chemist, for example, by writing a literature review in the style of what would be in a journal article than they would just writing an annotated bibliography.

3. High-stakes writing can foster engagement by:

Offering opportunities for connection with the instructor(s). When students receive feedback on high-stakes writing assignments from their instructor, especially in the drafting process, it allows for student-instructor connections. These connections can be fostered through written feedback and one-to-one student-instructor conferences about writing. Check out our sections on feedback and conferencing for more details.

Offering opportunities for connection with peers. When peer review is built into high-stakes writing assignments, students have the opportunity to get feedback from one another. Peer review also affords students the opportunity to encounter other students’ writing. Check out our section on peer review for more details.

Offering opportunities for connection with course content. Eodice and colleagues (2016), in their book The Meaningful Writing Project, found that writing projects are meaningful when they “offer students opportunities to make personal connections to the topic, the processes, or the genre of writing.” Personal connections can be wide-ranging; students may write about their passions, family or friends, communities, and more.

4. High-stakes writing can build accessibility into a course by:

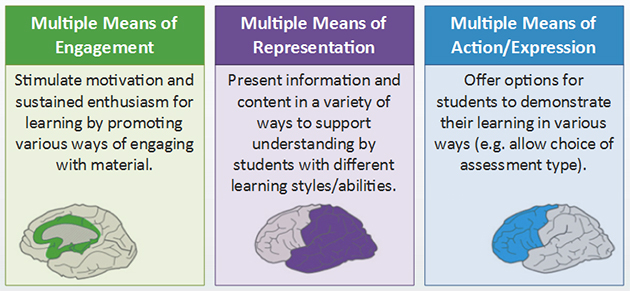

Providing multiple means of engagement. High-stakes writing offers students with a different way to connect to course material than through tests or quizzes.

Providing multiple means of representation. High-stakes writing provides students with a different way to learn material.

Providing multiple means of action and expression. High-stakes writing provides students with ways to show their thinking and understanding of a topic. Offering students multiple different means of communicating their learning—for example, producing videos, podcasts, or mixed media compositions—can ensure that all students, including students with disabilities, have the opportunity to demonstrate their knowledge or expertise with the writing task.

5. High-stakes writing can build equity into a course by:

Promoting learning rather than gatekeeping. “Gatekeeping” is the conscious or unconscious determination of whether students belong in an exclusive group of “top students” or “future professionals.” High-stakes writing can be designed to be gatekeeping, or, alternatively, to promote learning. Assignments are not a neutral component to student experience in your class. Along with course syllabi, policies, rubrics, and more, assignments are part of a larger “ecology” of assessment—that is, systems of judging student learning and performance (Inoue 2015). The assessment ecology of your course shapes not only what but how students learn, and it does so in ways that can be either inclusionary or exclusionary.

| Exclusionary (Gatekeeping) | Inclusive (Promotes Learning) |

| “How can this assignment weed out those who didn’t do the work?” | “How can this assignment help everyone in the class access, engage, and learn course concepts?” |

| Assignments as a benchmark to appraise content proficiency | Assignments as a way to encourage students to demonstrate their learning |

| Focusing solely on holding students accountable to performance standards | Giving students the opportunity for critical self-evaluation |

| Students must compete with peers to achieve a high rank | Students should be in conversation with peers and instructors to learn and grow |

Inclusive assignment design foregrounds an understanding of learning as a complex process abetted by multiple and recursive means of engagement. It also acknowledges the social and affective (as well as cognitive) dimensions of learning. In short, truly effective assignments help to ensure equitable education across a diverse student body.

Offering the opportunity to promote linguistic justice. Linguistic justice is based on the premise that all languages and language variations are legitimate and equal. Truly effective—that is, inclusive and equitable—assignments support rather than penalize the diverse varieties of English used by our students. This can be accomplished by providing transparency around the myth of “standard” English (i.e. even formal, written English varies across contexts); opportunities for translanguaging, when possible; and feedback on conventions in English grammar, syntax, and idiom.

Writing in specific genres can also be an action towards linguistic justice. When students write just a typical academic essay, their audience is usually seen as a highly privileged audience and we have traditionally expected that students write in a tone and dialect to match this expectation. However, when we ask students to write, for example, a news piece to be published in their home community about climate change, their audience is now their own community and they can choose the language that best suits this readership. Writing for their community allows marginalized students a chance to bring their personal experiences into the classroom as an asset rather than a deficit. No matter the genre, providing a specific genre with designated readers, context, and purpose gives students a specific reason to choose the dialect appropriate to the genre rather than setting the arbitrary standard of Standard Academic English.

For more information about linguistic justice, check out the section in this Pressbook on supporting multilingual students.

References

Carter, M., Ferzli, M., & Wiebe, E. N. (2007). Writing to Learn by Learning to Write in the Disciplines. Technical Communication, 21(3), 278–302.

Eodice, M., Geller, A. E., & Lerner, N. (2016). The meaningful writing project: learning, teaching, and writing in higher education. Utah State University Press.

Melzer, Dan and John C. Bean. Engaging Ideas : The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2021. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/wisc/detail.action?docID=6632622.

Inoue, Asao B. Antiracist Writing Assessment Ecologies: Teaching and Assessing Writing for a Socially Just Future. WAC Clearinghouse. Fort Collins: 2015.