Main Body

Chapter 2: A Fieldschool Approach

Anna Andrzejewski

The class was based at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where similar fieldschools have been taught in the summers periodically since 2006.[1] The idea of a fieldschool is based on the notion that content is generated through “fieldwork.” Fieldwork places students in face-to-face situations with their subjects, whether that means buildings/artifacts or contemporary citizens and organizations. The idea is to gather primary research and use those findings at the basis for generating original scholarship. In short, our goal was to learn new information about the architecture and history of this area through immersive study in the local community.

The premise of this is tied to the academic discipline of material culture studies. This field is premised on the notion that human-made things – such as furniture, ceramics, clothing or even houses – are intertwined with our everyday lives. Because of this, it is assumed that studying these kinds of things can reveal things about culture, including things that are not in the written record. The study of common architecture – what some term vernacular architecture – is one subject of material culture studies.[2] The project team relied on approaches derived from the discipline of material culture studies to learn about these buildings and create fresh research findings.

Of course this research was not conducted in isolation. The team drew on scholarship several generations in the making about the architecture of Germans from Russia, which has long been hailed as a definitive feature of the historic building fabric of the region as well as other parts of the Great Plains. As this chapter explains, the project team attempted to use primary data from our fieldwork to build on previous research, which offered some fresh insights and suggested potential avenues for future study.

Previous Research

The architecture and history of the Germans from Russia has been subject to study at the international, national, regional, and local levels. Much research on this group has benefitted from robust historical organizations and collections, namely the Germans from Russia Heritage Collection at North Dakota State University, the Germans from Russia Heritage Society, and the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia.[3] These organizations hold archival collections, especially genealogies, which are designed to educate descendants about their heritage. These collections are supplemented by other collections specializing in the architecture and history of the northern Great Plains. Of particular note are collections at the State Historical Society of North Dakota and a consortium of resources grouped under the collection “Digital Horizons.”[4] Collectively these resources provide excellent background on the history of the Germans from Russia in North Dakota, the kinds of buildings and structures they lived in and used, and some information on the history of people as they migrated from parts of eastern Europe to the northern Great Plains.

The team was also indebted to scholarship conducted on buildings in the region, which includes published articles, essays, and books as well as previous reconnaissance studies, historic resource surveys, and historic contexts. Insight into understanding North Dakota’s settlement history was gleaned through Plains Folk: North Dakota’s Ethnic History, an edited volume with essays on diverse ethnic populations who settled in the northern plains.[5] Scholarship on the architecture of Germans from Russia in North Dakota is limited; it includes an unpublished paper from a conference, a short essay in an edited volume on America’s ethnic vernacular architecture, and a more in-depth published article in Pioneer America centered on the community of Schefield.[6] Additional studies on ethnic barns and churches were helpful in understanding the broader cultural landscape.[7]

Previous studies done in the region for preservation planning purposes were also very helpful for background. The team made extensive use of “Ethnic Architecture in Stark County, North Dakota: A Historic Context.”[8] Prepared in 1992 with funding from the National Park Service, the context laid out property types associated with the different ethnic groups that settled the county while also prioritizing goals for preservation. While helpful in many ways, the study looked at a much broader area than our project. Moreover, many resources have been lost since the report’s completion, something that makes our project all the more timely. Recent survey work done as part of compliance with federal regulations was also helpful in helping the team strategize research priorities.

Finally, several HABS/HAER studies and previous survey work in the surrounding region, such as at the Hutmacher Farm (Dunn County), were helpful as comparative material.[9]

Project Methodology

The class was organized into a four-week session with the “field week” to occur during the second week of the course.

The students spent the first week of class reviewing previous studies and scholarship, becoming familiar with research resources and developing skills in drawing and interviewing to use in the field. The second week was spent in Stark County conducting intensive field survey of seven farmsteads while also conducting five interviews with individuals knowledgeable about the history of these farms, the architecture of the Germans from Russia, and the region’s settlement history. The final two weeks of class were spent in Madison processing the data collected in the field and developing content for the e-book.

The team went into the field with predetermined research questions. These research questions developed out of the students’ interests as well as their knowledge of previous literature. The students were most curious about what they perceived as gaps in existing scholarship. They tried to use what they found in the field to build knowledge that they found lacking in other sources. Although the team veered from these questions in the field, they still served as a useful starting point.

Professor Andrzejewski identified priorities for field research based on the Historic Resources Survey conducted in Hettinger and Stark Counties by Tetra Tech in 2016. The farms chosen seemed to embody features associated with early twentieth-century German-Russian building as discussed in the existing literature and had a fairly high level of architectural integrity.

In selecting the sites, the PI tried to prioritize farmsteads with significant numbers of outbuildings rather than sites with only one or two buildings (except in cases where those buildings had a high level of integrity–in terms of few additions or changes in terms of their material, form, setting, location, or ornament–or were otherwise significant because of their early date of construction or being of an exceptional type).

All of the farmsteads examined had buildings dating to the first quarter of the twentieth century, with most (though not all) of the farmsteads under construction by the date of publication of the local atlases in 1914 (Stark County) and 1917 (Hettinger County).[10] As will be shown in Chapters 5 and 6, these farms represented a range of choices to homesteaders in the region of German-Russian background. While folk in nature, they also suggest ways that their builders and owners accommodated and acclimated to the Great Plains in terms of placement, materials and methods of construction, and building form. Collectively they show significant variety in terms of farm layout, house form and materials, and outbuilding options despite the fact they were produced for people associated with a particular ethnicity.

The day before entering the field, the field team reviewed the research questions and properties for study. Given time constraints (only a week for fieldwork) and the fact the focus was only on seven farms, the PI settled on a deductive approach for the fieldwork. The team agreed to study the farmsteads with the goal at the end of trying to tell a story through the field evidence, weighing that against the findings of previous research. The fact the property owners allowed fairly unlimited access to their farms allowed the team to ask nuanced questions of the buildings and their relationship to one another and the landscape. The team considered everything from farm layout to individual types of buildings to details of construction and compared the farms to one another.

Methods

Although the fieldschool was building-centered, the field team relied on multiple forms of evidence as well as an assortment of research techniques.

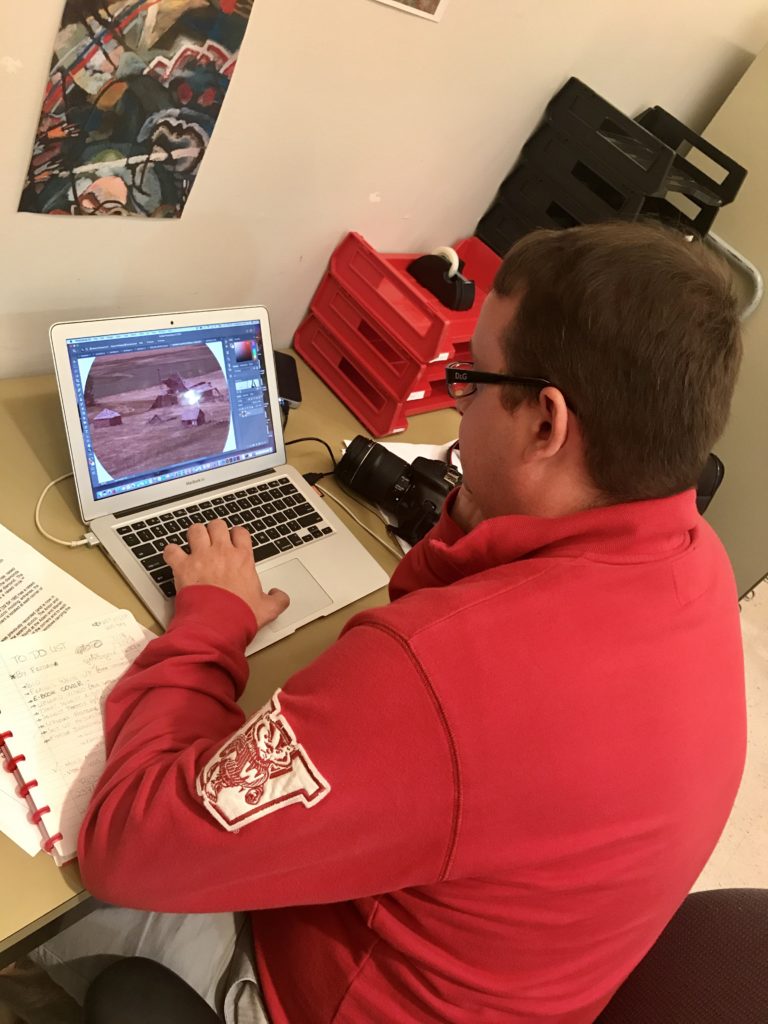

In the field, students learned skills in building documentation though measured drawing, photography, and interviewing. Once back in Madison, students honed their skills in graphic representation through creating scaled measured drawings, designing interpretive maps, choosing representative photographs, and editing video and audio tracks.

Measured drawing had the steepest learning curve for students in the class. Using tape measures and graph paper, students learned how to recreate scaled plans, elevations, and construction details. The students drew by hand (rather than using Computer Assisted Drawing, or CAD) based on two core beliefs: first, that it would allow them to engage more directly with the buildings and notice details they might not otherwise see; and second, because the class agreed that the detailed appearance of these hand-crafted buildings would best be communicated through hand-drawing. Despite a rough initial morning, by the afternoon of the first day, students were drawing on their own, creating floor plans and elevations – and this work continued throughout the remainder of the week.

Simultaneous with drawing, certain members of the team branched off for other activities, namely photographic documentation, research, and interviewing. One of the students, Alex Leme, had extensive background in professional photography, and he was tasked with creating many of the high-resolution photographs in the e-book. Meanwhile, the PI conducted most of the interviews used in the book, peeling off other members of the team for assistance.

The interviews adhered to “best practices” in the field of oral history.[11] Team members obtained “informed consent” and adhered to the protocol approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison IRB. The questions asked were open-ended, but focused on the history of the Germans from Russia and their architectural legacy.

Once back in Madison, the class spent two weeks processing the data and preparing content for the e-book. Although each student participated fully in all aspects of preparing the e-book, each was given oversight over one aspect: Alex (photography and A/V editing), LauraLee (maps), Laura (drawings), and Michelle (archival research). Each student was also responsible for creating a narrative on one of the sites studied in the field. The PI concentrated on developing the e-book platform, writing interpretive parts of the narrative, and helping put all the different contributions together in this final product.

Benefits of a Fieldschool Approach

While such a short class can hardly be expected to produce the definitive word on such a rich topic as Germans from Russia architecture on the Great Plains, the e-book suggests the value of the “fieldschool approach.” The immersive week in the field was particularly valuable in connecting the project team with local residents and the individual sites. The team was able to gather rich primary data in the form of drawings, photographs and interviews and preserve those findings for future researchers. Compiling findings into an e-book also allows the data gathered to reach a larger audience than a typical report, and the team hopes this will prompt future research in the region on this under-studied architecture and this important ethnic group.

- For fieldschools taught at UW-Madison and the UW-Milwaukee in previous summers, visit https://blcprogram.weebly.com/fieldwork-archive.html ↵

- For an introduction to material culture, see James Deetz, In Small Things Forgotten: An Archaeology of Early American Life (New York: Vintage Books, 1977). A good introduction to the field of vernacular architecture is Camille Wells, "Old Claims and New Demands: Vernacular Architecture Studies Today," Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture 2 (1986): 1-10. ↵

- For information on the collections, visit the following websites: https://library.ndsu.edu/grhc/; http://www.grhs.org; http://www.ahsgr.org ↵

- For information, see http://history.nd.gov and http://digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/about . ↵

- William C. Sherman and Playford V. Thorson, eds., Plains Folk: North Dakota’s Ethnic History (Fargo, N.D. : North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies at North Dakota State University in cooperation with the North Dakota Humanities Council and the University of North Dakota, 1986). ↵

- Steve C. Martens and James W. Nelson, “From Dust to Dust…The Temporal and Organic German-Russian Folk Architecture of Western North Dakota’s Hutmacher Farmstead,” Unpublished paper given at the 1996 conference of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, Ottawa, Ontario; Michael Koop, “German-Russians,” in America’s Architectural Roots: Ethnic Groups that Built America, ed. Dell Upton (Washington, DC: Preservation Press, 1986), 130-35; and Alvar W. Carlson, “German-Russian Houses in Western North Dakota,” Pioneer America 13, no. 2 (September 1981): 49-60. ↵

- Lauren Hardmeyer Donovan, Prairie Churches (Fargo: Preservation North Dakota, 2012) and Prairie Barns of North Dakota (Fargo: Preservation North Dakota, 2015). ↵

- Lon Johnson, et al., “Ethnic Architecture in Stark County, North Dakota: A Historic Context,” prepared for the Division of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, State Historical Society of North Dakota by Renewable Technologies and Michael Koop, subconsultant, 1992. ↵

- Hutmacher Complex, HABS Report, Killdeer, Dunn County, North Dakota, HABS ND,13-KILLD.V,1-. ↵

- George A. Ogle, Standard Atlas of Hettinger County, North Dakota (Chicago: Geo. A. Ogle and Co., 1917) and Standard Atlas of Stark County, North Dakota (Chicago: Geo. A. Ogle and Co., 1914). ↵

- See "Principles for Oral History and Best Practices for Oral History," Adopted October 2009 by the Oral HIstory Association at http://www.oralhistory.org/about/principles-and-practices/. ↵