Main Body

Chapter 4: The Schefield Community

Michelle Prestholt and Anna Andrzejewski

Our study centered in a rural part of Stark County, near the historic Village of Schefield. Until it closed in 1990, St. Pius Catholic Church was the anchor of this tiny rural community, drawing Catholic parishioners from the surrounding farms for worship. At one time, the community also boasted a store, a Catholic school, and an active Verein hall. Today the community is a ghost of its former self, with only a few residences, the cemetery, and the Verein hall suggesting the history of this century-old village that was once the center of the German-Russian community in this part of Stark County.

Because of the proximity of the farms in our study area to Schefield and given the connections of families we interviewed to St. Pius, we chose to undertake an analysis of surviving historical records in attempt to contextualize the farms we studied within the broader “Schefield community.” That community proved far more diverse than we anticipated, something borne out by interviews we conducted with residents in the area. Although many of the families who attended St. Pius were, indeed, of German-Russian background, we found a much more mixed ethnic fabric in the vicinity of Schefield, consisting not only of German-Russians but also a sizable number of German-Hungarians and people of other ethnic backgrounds. Over time, this ethnic diversity became even more pronounced, and mixing occurred between people of different ethnic backgrounds. By the time St. Pius was demolished in the late 1990s, the sense of the German-Russian history of the community had been reduced to the names in the cemetery and the memories of a few descendants of the original homesteaders.

The History of St. Pius and Schefield

Outside of a few residences, the only historic buildings today that reflect Schefield’s century-long history as a center of the German-Russian community are the former parish house, a little used Verein Hall, and the St. Pius cemetery.

The grave markers in the cemetery are full of German surnames, including some still common in the area, such as Binstock, Steier, Frank, Olheiser, Ehlis, and Weiler. Also notable are the numerous iron cross grave markers, a feature found in many German-Russian cemeteries in the region.[1] A model of the former St. Pius is located in the cemetery as if to commemorate the rural church and its German-Russian founders.

Indeed, when it was built, St. Pius was an anchor within the German-Russian community in Stark County. When St. Pius parish formed in 1910, the County had just experienced its largest period of growth; the county grew from a population of 7,621 in 1900 to 12,504 in 1910.[2] A cursory look at the Population Census reveals much of this population growth came from immigrants from Russia, particularly German-Russians. The longtime pastor of St. Pius, Bede Dahmus (priest from 1933-90), describes the community as it formed around the church in parish records at the Bismarck diocese:

“The first settlers were German-Russians who took up homesteads from the government. When a post office was to be established at the parish house the name “Schoenfeld” was suggested, after the name of a parish or town in Russia. This was corrupted to Sheffield.”

When asked to describe the nationality of the early parishioners, Father Dahmus stated simply, “German-Russian.” [3] Schefield was at one time a thriving village, boasting several stores, a service station, a blacksmith shop, and more than a dozen homes.[4]

The modest Catholic parish succeeded in attracting a sizable congregation in its early years. Its initial membership numbered around sixty families. But according to local historian Nick Olheiser, the parish boasted over 130 families by 1933.[5] Initially services were held in the basement during construction of the Church in 1910-11, which was completed in 1912. It was built to house up to 320 parishioners, and measured

49 x 110 ft in size (with a substantial steeple and stained glass windows). The Parish house, a sizable foursquare dwelling, was completed in 1914. The school building was finished in 1928, marking nearly a decade of growth after the original school had opened in the basement of the Church in 1917.[6]

The Catholic school had robust enrolments through World War II, and supported a high school for a time in the 1930s. Nuns from the School Sisters of Notre Dame (of Mankato, Minnesota) ran the school until 1968.[7] By that point enrollment had gradually dwindled; in 1976, St. Pius enrolled only 44 students. It closed in 1984 with only 19 students.[8]

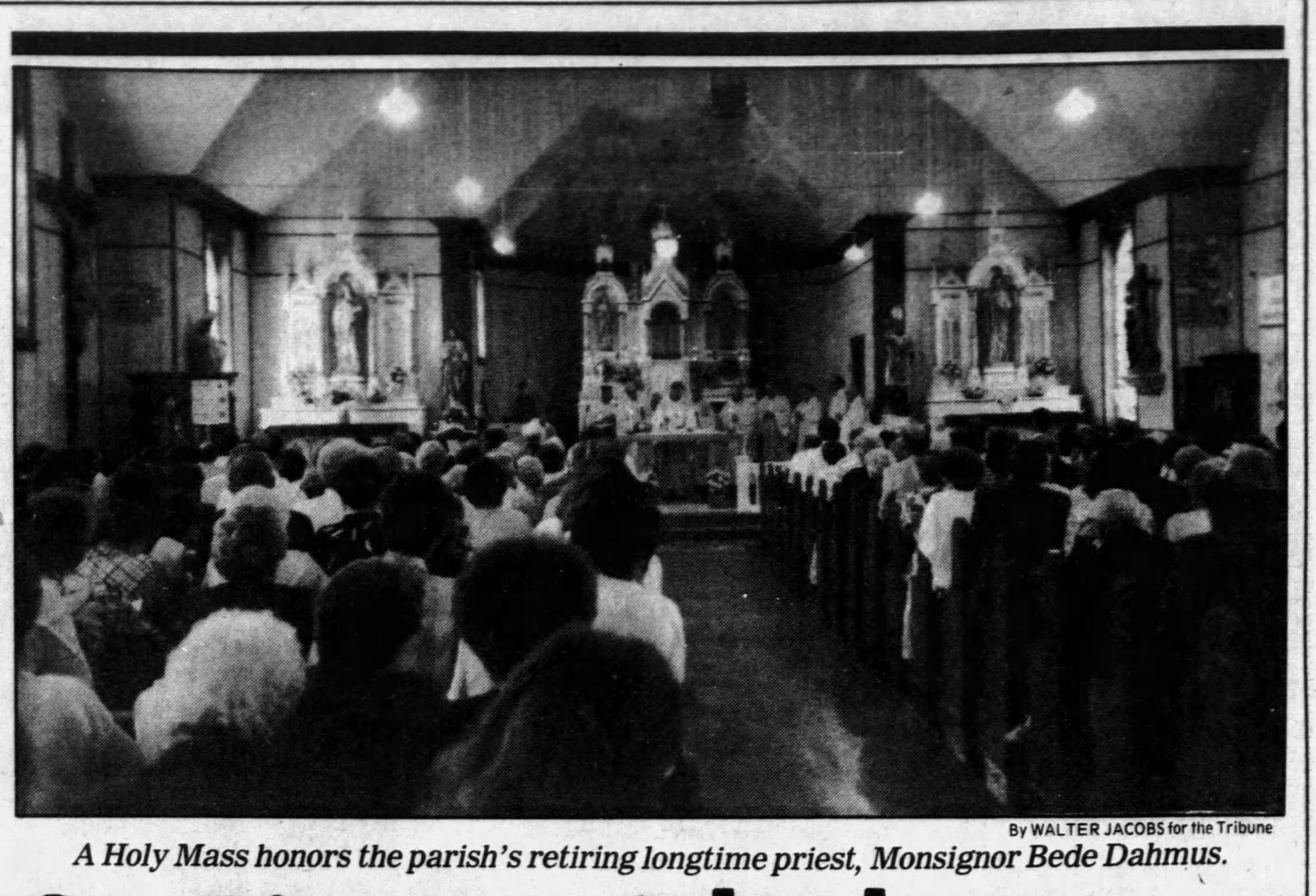

The school’s slow decline is related to that of the parish generally, whose membership also shrunk over the same time period. An undated source in the Bismarck Diocese says membership in the 1980s hovered around 35 or 40 families. The church closed its doors with a service on Sunday, April 22, 1990, which drew worshippers “coming from a long distance” and filled the Church to capacity.[9]

The church and school were demolished in 1998.[10] Although the Verein hall is reported to be active, we tried without success to find anyone to help us determine the membership today.

Nick Olheiser was interviewed for the Dickinson Free Press in 2012. Recounting the stories he knew of the Church, school, and Verein hall, Olheiser commented tellingly on the gradual decline of the community, including the moving of buildings and demolition of others: “It was a let-down, not so much for me, but the ancestors who put the effort into building them and taking care of them.” For Olheiser as well as others, the decline of Schefield represented the end of something they associated with their German-Russian roots – and yet looking to other records suggests the Schefield community was always more ethnically complex.

Delving into the Archives

In order to gauge the extent of the German-Russian nature of the Schefield community, the class spent time examining textual records, attempting to correlate information from the 1914 Atlas of Stark County, census records, and burial records at St. Pius. The analysis produced a much more complicated picture of the “Schefield community” than is generally believed. While St. Pius may have been founded, as Father Dahmus suggested, specifically for German-Russians, the surrounding community was always, to an extent, ethnically diverse, something that has continued to expand over time.

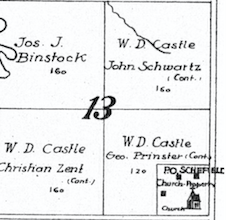

Beginning with the assumption that the “Schefield community” was partly geographical, we began with the 1914 atlas.[11] We decided to collect surnames within a roughly four mile radius of the church, which corresponds generally with Township 137, Ranges 97 and 96 W in the Atlas. After collecting those surnames, we cross-referenced them with the surnames in the 1910 census, Districts 0164 and 0167, which included Ranges 97 and 96 W. If the 1914 landowners were not included in the 1910 records, they were excluded from our data analysis. Overall, there were 160 surnames on the 1914 map, and census data was found on about half (72) of them. We then extracted data on gender, age, birthplace, language spoken, and literacy from the census records on the families.

Based on this data, we extrapolated some interesting data about the population of the Schefield community. 42.94% of the community was born in Russia, with the remainder being born either in North Dakota (38.04% – mainly children) and Hungary (13.54%). The linguistic picture is also fascinating. German was overwhelmingly the dominant language with 75.1% of the population speaking it. English was a distant second (20.55% of the population), and Russian third (4.35%). When we look at the household level, the majority of the households were “German from Russia,” but 14 were identified in the 1910 census as “Germans from Hungary.”[12]

We further analyzed the ethnic breakdown of the ownership map using information on landowners’ birthplaces gleaned from the 1910 census, as well as naturalization records, data from the 1920, 1930, and 1940 censuses, and draft cards. We felt comfortable mixing data sources since we were only trying to establish place of birth to obtain a sense of the ethnic backgrounds of the Schefield community. We then color-coded the landowners on the map based on their birthplace in order to visualize the community geographically. Surprisingly, there was no clear division between Russian and Hungarian families. Although Germans from Russia clearly outnumbered those from Hungary, over the course of the period from 1910-1940, Germans from Hungary dispersed through the area rather than sequestered themselves in clusters.

We also attempted to cross-list the last names of the landowners from the 1914 Indexed County Land Ownership Maps with the names of individuals buried in St. Pius Cemetery using Find-a-Grave.[13] We did not exclude any of the landowners. Thirty-six family names were present on both the ownership maps and the St. Pius burial list. Of those 36, 94.4% were born in or related to someone born in Russia. This information suggests that the St. Pius community was dominantly made up of Germans from Russia, even if the larger Schefield community was more diverse. More in depth analysis of the cemetery records, especially parish records, would likely nuance this finding.

Conclusions

Our analysis of the Schefield community using multiple data sources reveals several things. First, the community clearly has German-Russian roots. The dislocation that these immigrants felt on coming to the Dakota frontier and settling on widely dispersed farms (a sharp contrast to the clustered settlements back in Russia) was likely mitigated by the closeness they felt from the connection to St. Pius parish. And yet the Schefield community was never solely German- Russian. These settlers came to Stark County alongside other immigrants from eastern Europe and Russia, including the German-Hungarians. Although German-Hungarians clustered their settlement in the vicinity of Lefor (and St. Elizabeth’s parish), our analysis showed there was always crossover between the groups geographically.

Interviews conducted as part of this study confirms these findings. Geneva Steier talks about the blending that occurred; though Geneva and her husband were of German-Russian descent, there was always some intermixing:

Oh, I would say that most Germans married Germans and some, once in a while, there were also people around here that came from the Ukraine…my daughter is married to a fella who is Bohemian, you know. Ah, some of those intermarried, too, you know.

Pete and Marie Betchner of Dickinson also talked about this variety in Stark County (and North Dakota more broadly):

The German-Hungarians settled around Gladstone and Lefor…the German-Russians, they settled around a lot around Dickinson….and if you go north of here then you have the Bohemians and if you go twenty miles that way then you have the Ukrainians, which basically, they all live kinda by the same rules and had a lot of the same tradition but they had their own individual characters about them and some of them had their own languages, like the Ukrainians talk different.

Even though groups lived in close geographical proximity, the boundaries between groups mattered, even as recently as fifty years ago.

Still, if the community was always diverse, the immigrants initially had much in common, not the least of which was the German language. George Ehlis recalls going to the St. Pius school as a boy, and having to learn English there:

When I started school, I couldn’t speak English, and it was a Catholic school, taught by nuns, and I was put in the back of the classroom because I couldn’t communicate. Which was unusual, because we lived away from that Schefield community, we were on the edge of it…certain areas had even isolated us. We spoke German, where the people who lived closer to the Schefield Community were bilingual…me and another boy that couldn’t speak English and we learned how to speak English by observing.

Just like German Hungarians who went to school in Lefor, Ehlis and his friends, of German-Russian descent, shared this in common.

Our analysis also suggested how the Schefield community has changed over time. Inevitably, as individuals moved from country to city and the rural population dwindled, so, too, did the role of rural institutions, like the church at St. Pius. As the community has urbanized and modernized, signs of ethnic identification have given way to a more regional identity, something more “North Dakotan” than German-Russian. So, too, have the buildings, markers of ethnic settlement on the frontier, been abandoned, reduced to rubble, or demolished. Schefield, a once thriving center of German-Russian life is a ghost of its former self, with the Verein hall and cemetery being the last reminders of the history of the community’s German-Russian homesteaders.

- Nicholas Vrooman, et al., Iron Spirits: Germans from Russia Iron Crosses in North Dakota (Fargo: North Dakota Council on the Arts, 1982) and “German-Russian Wrought-Iron Cross Sites in Central North Dakota,” Multiple Property National Register Nomination, #64500379, https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/AssetDetail?assetID=e3fb36b8-81f1-45bb-8c49-8dadaf9d20af. ↵

- U.S. Census, Schedules of Population, Stark County, ND, 1900 and 1910. ↵

- “Historical Record” (1945), St. Pius parish, in collection of Diocese of Bismarck, ND. ↵

- Linda Sailer, “Schefield Filled with Memories,” Dickinson Free Press, June 3, 2012 (http://www.thedickinsonpress.com/lifestyles/1816417-schefield-filled-memories). ↵

- Sailer, “Schefield Filled with Memories,” (http://www.thedickinsonpress.com/lifestyles/1816417-schefield-filled-memories). ↵

- For more information on the construction of the school, church, and parish house, see Nick Olheiser, “History of St. Pius Parish, Scheffield, North Dakota, 1910-1976, located at the Germans from Russia Heritage Society, Bismarck, ND. ↵

- For more on the nuns that ran the school see https://www.ssndcentralpacific.org/explore/location/our-lady-of-good-counsel ↵

- Olheiser, History of St. Pius Parish, and Olheiser, History of St. Pius Parish and St. Pius School, Scheffield, North Dakota, 1910-1986, also at the Germans from Russia Heritage Society, Bismarck, ND. ↵

- Walter Jacobs, "St. Pius Parish Closes," Bismarck Tribune, April 27, 1990. ↵

- Sailer, “Schefield Filled with Memories,” (http://www.thedickinsonpress.com/lifestyles/1816417-schefield-filled-memories). ↵

- George A. Ogle and Co., Standard Atlas of Stark County, North Dakota (Chicago: Geo. A. Ogle and Co., 1914). ↵

- U.S. Census, Schedule of Population, Stark County, ND, 1910. ↵

- On St. Pius cemetery records, see https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/636344/memorial-search?firstname=&lastname=Schoch&cemeteryname=. ↵