Main Body

Chapter 3: From Germany to Russia to the North Dakota Frontier

LauraLee Brott and Anna Andrzejewski

Introduction

The story of the migration of the German people to Russia (and parts of Eastern Europe) and eventually to North America – and North Dakota in particular – is complex. Much of scholarship about these people emphasizes how they retained aspects of their German culture as they migrated.[1] Less discussed are how elements of German-Russian culture came to be integrated with American culture as well as how this culture blended with that of other frontier settlers of German-Hungarian, Bohemian, Norwegian and Polish heritage. These and other ethnic backgrounds settled in the Great Plains in the same period as the Russian-Germans, which ultimately helped shape a new and distinctive regional culture on the northern plains.

This chapter traces the history of the German migration to Russia and eventually to North Dakota. Although the category “Germans from Russia” describes a large portion of the homesteaders who settled in southwestern North Dakota, they were not the only settlers in this region. In Hettinger and Stark Counties, Germanic speaking people from other parts of Eastern Europe – Hungary, for example – settled on farms that in some ways appear to resemble farms within our project area (stone construction and one-story linear form). Detailed fieldwork of the sort conducted for this e-book is one way to more accurately account for the particular and distinctive features of the architecture of the Germans from Russia.

From Germany to Russia (and elsewhere)

The story of the Germans from Russia in North Dakota begins in Europe. Of course, Germany as we think of it today was not an organized political entity until the organization of the German Empire in 1871 under the leadership of Bismarck.[2] Prior to this, it was a loose agglomeration of political entities, some large and some small, vying for power and control. Religious differences also divided those claiming German ancestry, with many of these differences dating back to the time of the Protestant Reformation. Wars between different political entities affected the fortunes of many Germans as much as the lingering feudal system and religious differences made life miserable for many of them. These “push factors” accounted for a nearly constant exodus of Germans to North America, other parts of Europe, and Russia during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[3] Large numbers of Germans settled in eastern North America (Pennsylvania and the Shenandoah Valley through 1800, and parts of the Midwest afterwards), in parts of Eastern Europe (Hungary, Romania, and Bohemia), and along the Volga River and the north shore of the Black Sea in Russia.

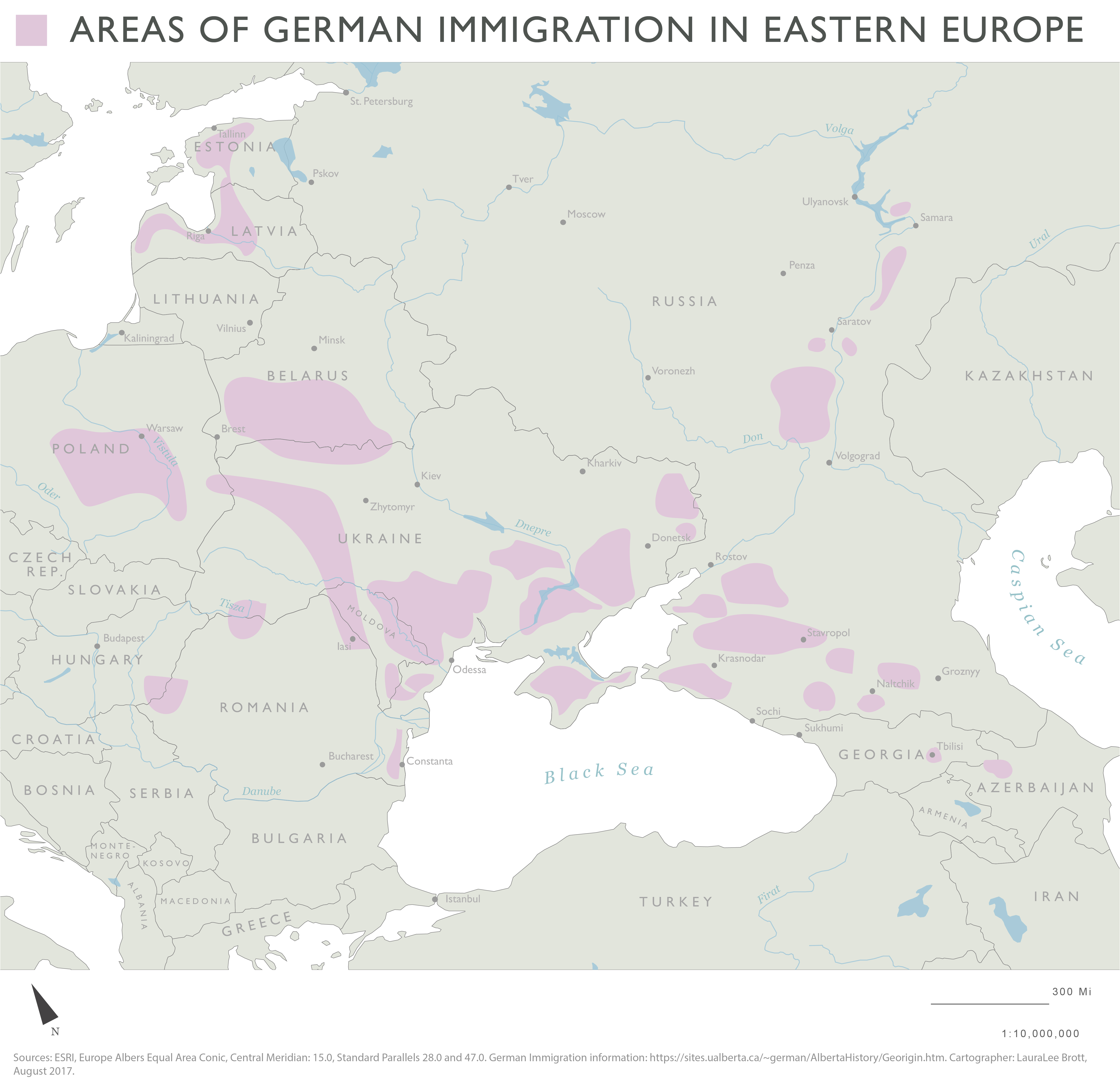

The Germans migrated to Russia in several waves, all spurred by promises of jobs and land from the Tsars. The first period of migration from Germany to Russia occurred between 1533-1584 under Ivan the Terrible, who hired a wide variety of tradesmen to build up Moscow.[4] The second wave of immigrants came between 1672-1725 under Tsar Peter the Great. By that time, there were 50,000 Germans living in St. Petersburg. The third wave was a result of Catherine the Great’s attempt to buffer the eastern parts of the empire against Asiatic tribes.[5] Alexander I continued this endeavor. Germans poured into Russia between 1762 and 1796, and waves continued after that.[6] Many went to the Volga and Black Sea regions (see map 1). By 1897, there were almost 2 million people of German descent in Russia.[7]

Part of the appeal for the Germans to move to Russia is tied to conditions of their settlement as set out by Catherine the Great in 1763. According to historian Richard Sallet, for about a century after this, Germans in Russia were entitled to:

- Religious liberty

- Tax exemptions for ten years in cities and thirty years on the land

- Exemption from military service or civil service, against their will, for all time

- Cash grants for the purchase of buildings and cattle

- Equality with native Russians

- Exemptions on import duty for colonists up to 300 rubles per family in addition to the moveable property of each family

- Permission of professional people to join guilds and unions in Russian empire

- All lands allotted for the settlement of colonists were to be given for eternal time, not however as personal property but as the communal property of each colony

- Settlers were permitted to depart at any time after payment of a portion of assets they had acquired in the Russian empire.[8]

Black Sea and Volga Germans both tended to build their settlements in pockets. Farmers worked on their farms on the outskirts of town during the day, and then resided within the main village at night. The villages were active, having German-speaking churches, schools, recreational places for shopping and social activities. Many villages also had their own German language newspapers. Village construction varied between the two groups. In the Volga region, villages followed a checkerboard pattern with one main street intersected with several cross and parallel streets. The Black sea settlements are “street-villages” with cluster of farms bordering on a single main road. Churches – whether Protestant or Catholic – were typically located in the center of the Russian communities.[9]

The houses the Germans built in Russia were typically one story in height, and usually made of sandstone, limestone or brick. The walls were stuccoed on the outside and whitewashed on the inside. The gable end of houses faced the straight village street, which was up to one hundred yards wide.[10] The Germanic people were industrious, and used their surroundings to their advantage. For example, in forest regions of the Volga, such as the Volhynian region, the buildings were largely constructed with wood.[11]

The distinctive features of particular settlements resulted from clusters of families coming either from particular regions in Germany, from a particular religious background, or often both. Eventually there were over three thousand distinctive Germanic settlements in Russia. While these settlements differed in terms of their religion and particularly features, the settlers shared the native German language and held on to many German customs, at least initially. By 1871, when Tsar Alexander II revoked the privileges granted to the German-Russians under Catherine the Great’s charter, some accommodation to Russian language and lifeways had occurred but the swift action prompted many of Germanic descent to migrate again in search of new opportunities.[12]

From Russia to North Dakota

Tsar Alexander’s actions effectively ended equal treatment of German-Russians, making them essentially peasants and requiring the immediate drafting of men into the Russian army. While some endured, many German-Russians left for the United States and Canada. Like their ancestors, they were lured by similar prospects that prompted their move to Russia: the promises of free land and freedom to practice their own religion and culture.

Immigration to the U.S. began in earnest in 1872 after railroad companies distributed pamphlets throughout Europe and Russia, boasting of large tracks of affordable land in the Great Plains.[13] The Homestead Act of 1862 offered 160 free acres of farmland provided one improve and live on the plot for a minimum of five years. Of course, the Great Plains were not widely settled by white Americans or European immigrants until the transcontinental railroads entered the area during the last few decades of the nineteenth century.[14] The Northern Pacific Railroad entered the Dakota territory in 1872 and reached the city of Bismarck in 1873, opening up the northern Dakota territory for widespread settlement.[15] Settlement accelerated between 1880 and 1890 by nearly 1400% (from ~37,000 to over 190,000).[16] Between 1870 and 1920, 120,000 Germans poured into the U.S. from Russia.[17] North Dakota specifically held 23% of German-Russian population in the United States by 1920.[18]

Scholars have contended that the German-Russians who chose to settle in the Great Plains desired a landscape reminiscent of the Russian steppes they were used to cultivating.[19] It is true that Germans from Russia who came to the U.S. generally avoided urban areas, seemingly preferring the isolation of the rural landscape (though of course assurances of free land also made this appealing). Most of them were reasonably well off, and most were farmers, as local historian Kevin Carvell explained:

Most homesteaders were poor, but they were wealthier than many….they had enough money to get out here….to get a wagon, a horse, a pick…they had a little bit of money….the German-Russians were straight off the boat, and had been farmers for 10,000 years and had endured harsh lives in Russia when they emigrated there.

According to Richard Sallet, 95% of the Germans from Russia that settled in the Great Plains were wheat farmers.[20] As much as possible, the German-Russians migrated in groups and tried to settle near others of the same religion – whether Catholic, Lutheran, Mennonite, and Hutterite. The Homestead Act did not allow for settlement in rural villages; farmers had to reside on their 160 acre plots. In North Dakota, they tended to try to put their farms at the corners of the tracts of land so they lived in somewhat close proximity to one another.

The German-Russians who settled in North Dakota retained the German language in churches, schools and newspapers through at least the first World War. Before World War I, twenty-nine German newspapers were printed in North Dakota, but less than twelve survived afterwards. In general, those born in 1950 understood aspects of the German language but were not fluent speakers, suggesting a fall-off in German customs as the settlers acclimated to frontier life in the Great Plains.[21]

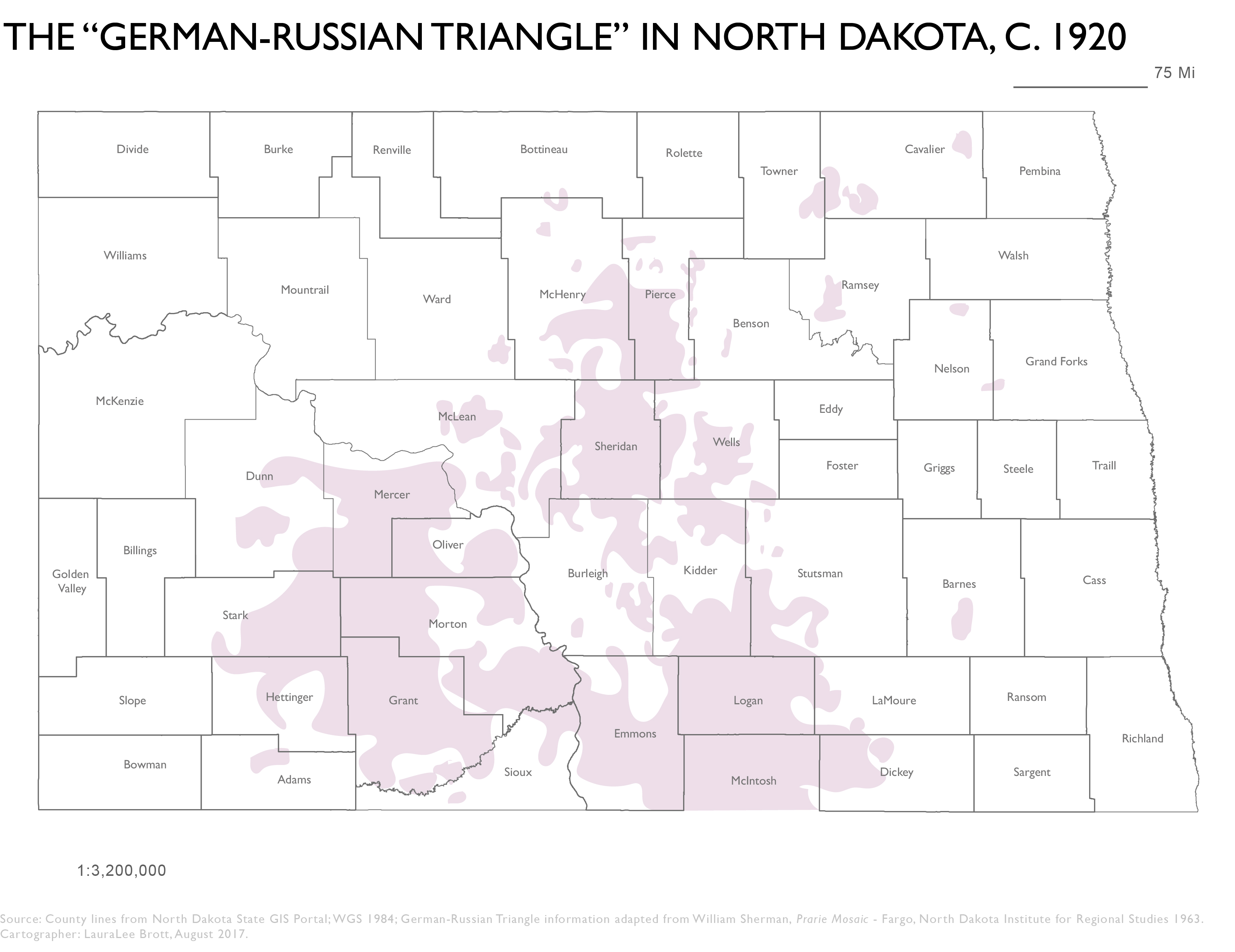

Germans in Southwestern North Dakota

The Germans from Russia are concentrated in three areas of North Dakota: south central, north central, and the southwest quarter (across the Missouri River), making what is called the German-Russian Triangle. 68,000 Black Sea Germans lived in this triangle in 1920; even in 1965, 97% of

households with German-Russian ties in North Dakota still lived in the triangle. Still, the Germans from Russia were far from the only ethnic group to come to this part of North Dakota in the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In addition to German-Russians, Germanic people from other parts of eastern Europe as well as elsewhere (Bohemia, Ukraine, Norway, Bulgaria, Poland and other parts of Europe and Asia) settled on the plains. As discussed by William Sherman in the Preface to Plains Folk: North Dakota’s Ethnic History, the legacy of North Dakota’s diverse ethnic settlement history remains in cultural traditions that are found in pockets of settlement even today.[22] But while members of these different groups settled in clusters, geographic boundaries were porous and never absolute. To isolate one group from another ignores the fact all were neighbors and that intermixing always occurred, even if it accelerated over time, and eventually became associated with a regional (as opposed to ethnic) identity.

The area around Dickinson serves as a case in point. It was settled during the 1890s principally by German-Russians from the Beresan region on the Black Sea.[23] More German-Russians flocked to the area south of Dickinson after 1900 and moved further southward into Hettinger and Slope Counties.[24] These German-Russians were joined by other ethnic settlement groups in Stark County, which included the German-Hungarians, Bohemians (and Crimean-Bohemians), Norwegians and Ukrainians.[25] Still, the German-Russians were dominant, in 1910 making up 40.6% of the county’s population and 46.6% in 1920, compared with the next largest group, the German-Hungarians, at 27.5% and 23.3%, respectively.[26]

While census numbers convey the dominance of the German-Russians, geographic distribution of people from different ethnic groups in Stark County tells a more complicated story. If the area south of Dickinson was dominated by German-Russians, other parts of the county had concentrations of people of other ethnic groups. Lefor, for example, was settled mainly by German-Hungarians from the Banat region of Austria-Hungary. Norwegians were concentrated near Taylor (and points north of there). Ukrainians settled in South Heart and Belfield, alongside German-Russians. When religion is added to the picture, the situation becomes even more complicated. Although German-Russians in the Schefield area were Catholic, German-Russians in Daglum were Lutheran. There were even Catholic churches for different groups which corresponded roughly to their geographic location in the county (German-Hungarians went to the church in Lefor, German-Russians to the church in Schefield). Even amongst those who shared the German language, then, their specific ethnic background affected where they settled, how they lived, and where they worshipped.

Although most of the farms examined in this e-book appear to have ties to German-Russian settlement in Stark County, they should be understood in light of this broader story – of German migration first to Russia and then to North Dakota, as well as in terms of the broader patchwork of ethnic settlement on the Great Plains. As later chapters will show, while some of the farms we studied have features that mark them as tied to “German-Russian” culture, features changed over time as their occupants co-mingled (and eventually intermarried) with people from other ethnic groups. The process of migration (and the acculturation that comes along with it) is thus important in understanding the history of these farmsteads.

- Richard Sallet, Russian-German Settlements in the United States, trans. Lavern J. Rippley and Armand Bauer (Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1974), 3-7. ↵

- R. R. Palmer and Joel Colton, A History of the Modern World (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984), 525-27. ↵

- Adam Giesinger, From Catherine to Khruschev: The Story of Russia’s Germans (Battleford, Saskatchewan: Marian Press, 1974), 6-8. ↵

- Sallet, Russian-German Settlements, 8-9. ↵

- “A Brief History of the Germans from Russia,” https://library.ndsu.edu/grhc/history_culture/history/history2.html (accessed November 20, 2017). ↵

- Sallet, Russian-German Settlements, 10-13. ↵

- Sallet, Russian-German Settlements, 13. ↵

- Sallet, Russian-German Settlements, 10. ↵

- Sallet, Russian-German Settlements, 14. ↵

- Sallet, Russian-German Settlements, 13. ↵

- Sallet, Russian-German Settlements, 14. ↵

- “A Brief History of the Germans from Russia,” https://library.ndsu.edu/grhc/history_culture/history/history2.html (accessed November 20, 2017). ↵

- Lon Johnson, et. al., “Ethnic Architecture in Stark County, North Dakota: A Historic Context.” Report prepared for the Division of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, State Historical Society of North Dakota by Renewable Technologies and Michael Koop, sub-consultant, 1992,5. ↵

- Sallet, Russian-German Settlements, 5; William C. Sherman and Playford V. Thorson, eds., Plains Folk: North Dakota’s Ethnic History, (Fargo, N.D.: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies at North Dakota State University in cooperation with the North Dakota Humanities Council and the University of North Dakota, 1986), 133-34; Stark County History, 4-6. ↵

- Johnson, et al., “Ethnic Architecture in Stark County,” 6. ↵

- “North Dakota Historical Population,” https://www.ndsu.edu/pubweb/~sainieid/north-dakota-historical-population.html (accessed November 20, 2017). ↵

- Sallet, Russian-German Settlements, 6. ↵

- Sherman and Thorson, Plains Folk, 137-138. ↵

- Michael Koop, “German-Russians,” in America’s Architectural Roots: Ethnic Groups that Built America, ed. Dell Upton (Washington, DC: Preservation Press, 1986), 130. ↵

- Sherman and Thorson, Plains Folk, 138, 148. ↵

- Sherman and Thorson, Plains Folk, 142. ↵

- Sherman and Thorson, Plains Folk, preface. ↵

- Alvar W. Carlson, “German-Russian Houses in Western North Dakota,” Pioneer America 13, no. 2 (September 1981), 51; Sallet, German-Russian Settlements, 38-39. ↵

- Johnson, et. al., “Ethnic Architecture in Stark County,” 12. ↵

- Johnson, et. al., “Ethnic Architecture in Stark County,” 8. ↵

- Johnson, et. al., “Ethnic Architecture in Stark County,” 9-11. ↵