Main Body

Chapter 6: Schefield Area Properties

This chapter contains research discovered by fieldschool students on five of the individual farms we investigated during the field school.[1] Each write-up contains a basic description of the farm along with interpretation related to the students’ area of interest, whether genealogical, architectural, or otherwise. These narratives along with the accompanying illustrations suggest the value of a “fieldschool approach” in both discovering new information as well as raising questions to be explored by researchers in the future.

Raymond Frank Farm

—Alex Leme

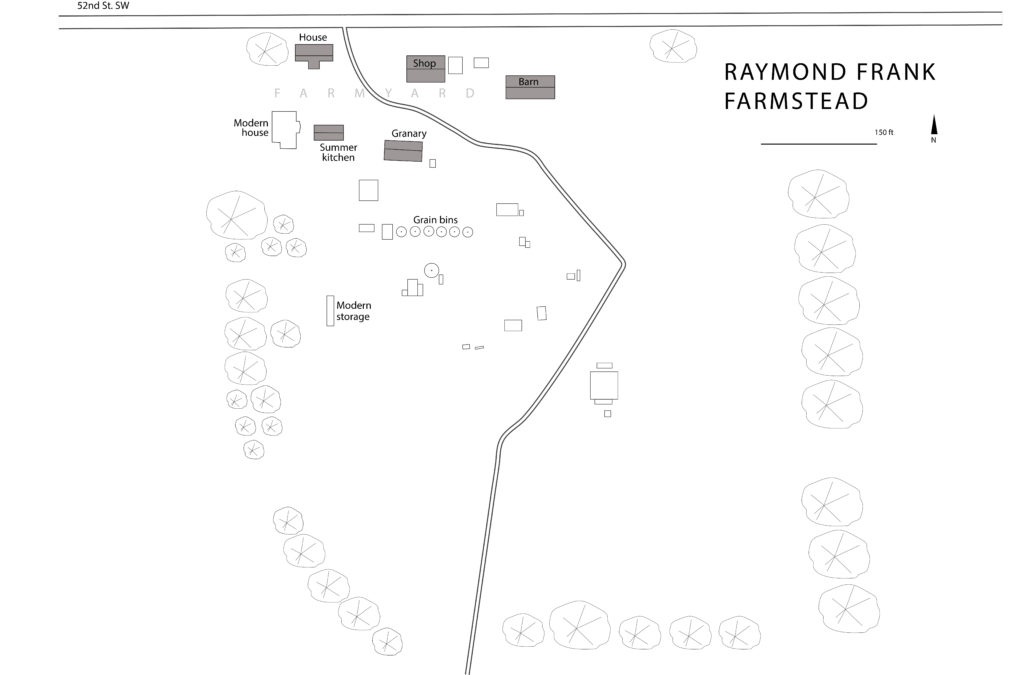

Nestled on rolling prairie, the Raymond Frank Farmstead consists of twelve buildings located on the south side of 52nd Street SW in Stark County. The farmstead comprises a historic house (built ca. 1907), a barn and a summer kitchen, and several other historic and modern outbuildings laid out in a courtyard plan.

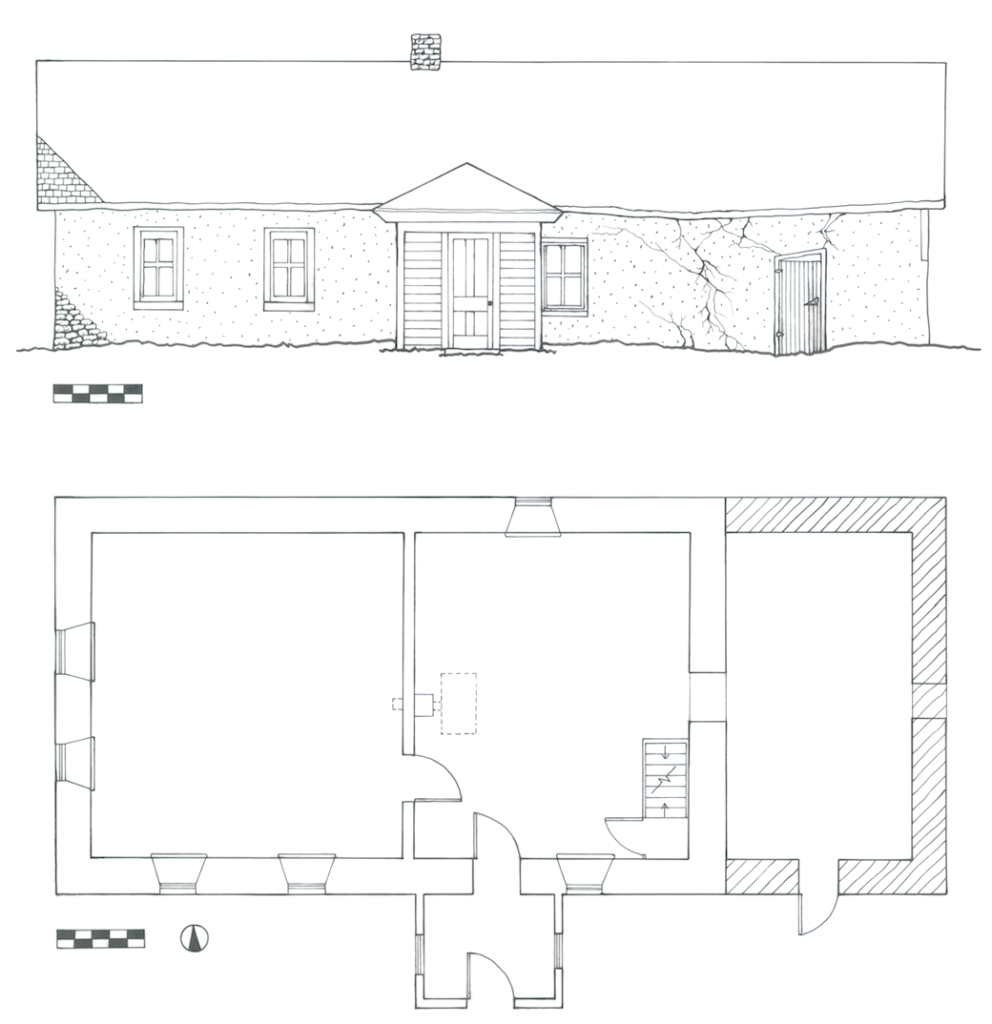

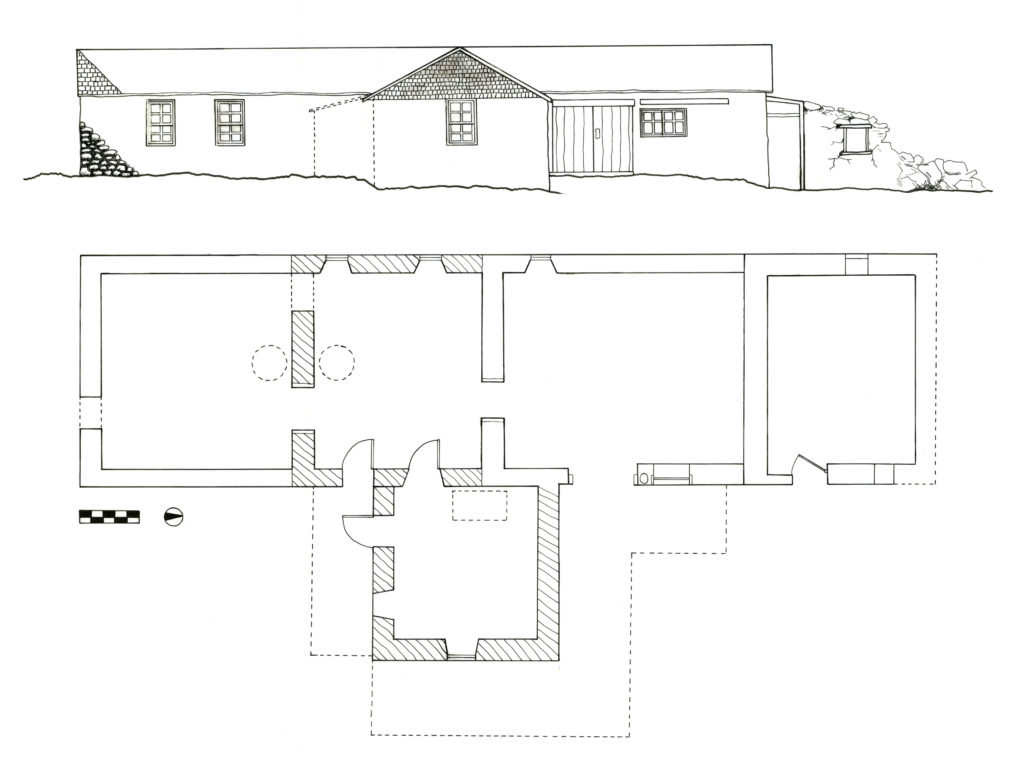

The historic house, very much in line with its Black Sea region counterparts, sits on an east-west axis, facing south away from the main road.[2] The single-pile, one-and-one-half story house is laid out in a linear rectangular plan, containing three rooms (also reminiscent of German-Russian vernacular domestic architecture). A coal shed makes up the eastern end of the house. A hipped-roof vestibule, or vorhäusl, extends off the front, or south, facade, and encloses the main entrance door.

The stone walls, which measure about 24 inches thick, are clad in white clay-plaster. According to William C. Sherman, the clay-plastered, white washed with lime to give a stucco effect, two-feet thick stone wall, as well as the vorhäusl were common features of the architecture of the German-Russian settlers.[3] While the stone wall on the western end of the house rises almost halfway into the gable end, the top part of the eastern wall consists of a wood-frame construction. The gabled roof is clad with wood shingles. The interior wall that separates the kitchen from the coal shed is made of stone, which suggests that the coal or storage room may have been added later.

The interior of the first floor is divided into a kitchen and a parlor-bedroom (Vorderstube). A narrow, steep staircase off of the kitchen connects the first story of the house to the two bedrooms upstairs. The interior walls are covered primarily in straw-clay plaster, with other walls and ceilings made of beaded board. There is no real foundation, so the walls are beginning to settle; floors are collapsing, wallpapers and paint to peel, and parts of the roof are held precariously in place. Upon moving their modern bungalow-style house from town to the farmstead site in the fall of 1965, the Frank family stopped living in the original stone house.[4]

The historic gambrel-roofed barn is located east of the house across a wide fairly open courtyard. Like the walls of the house, the ground level walls of the barn are made of uncoursed stones. The loft story, resting atop the stone walls, is wood-framed and sheathed with horizontal side boards. There are two large entry doors (on runners), one on each end of the east and west elevations of the building. There are two four-light windows and a smaller sliding door located on the west loft wall. The east loft wall has a large pair of hinged doors and a four-light window. A metal ventilator sits atop the center of the roof’s ridgeline. As reported by Jacob Frank, a grandson of the original homesteader, the barn was built in 1924 with the current wood-framed gambrel roof added in 1928.[5]

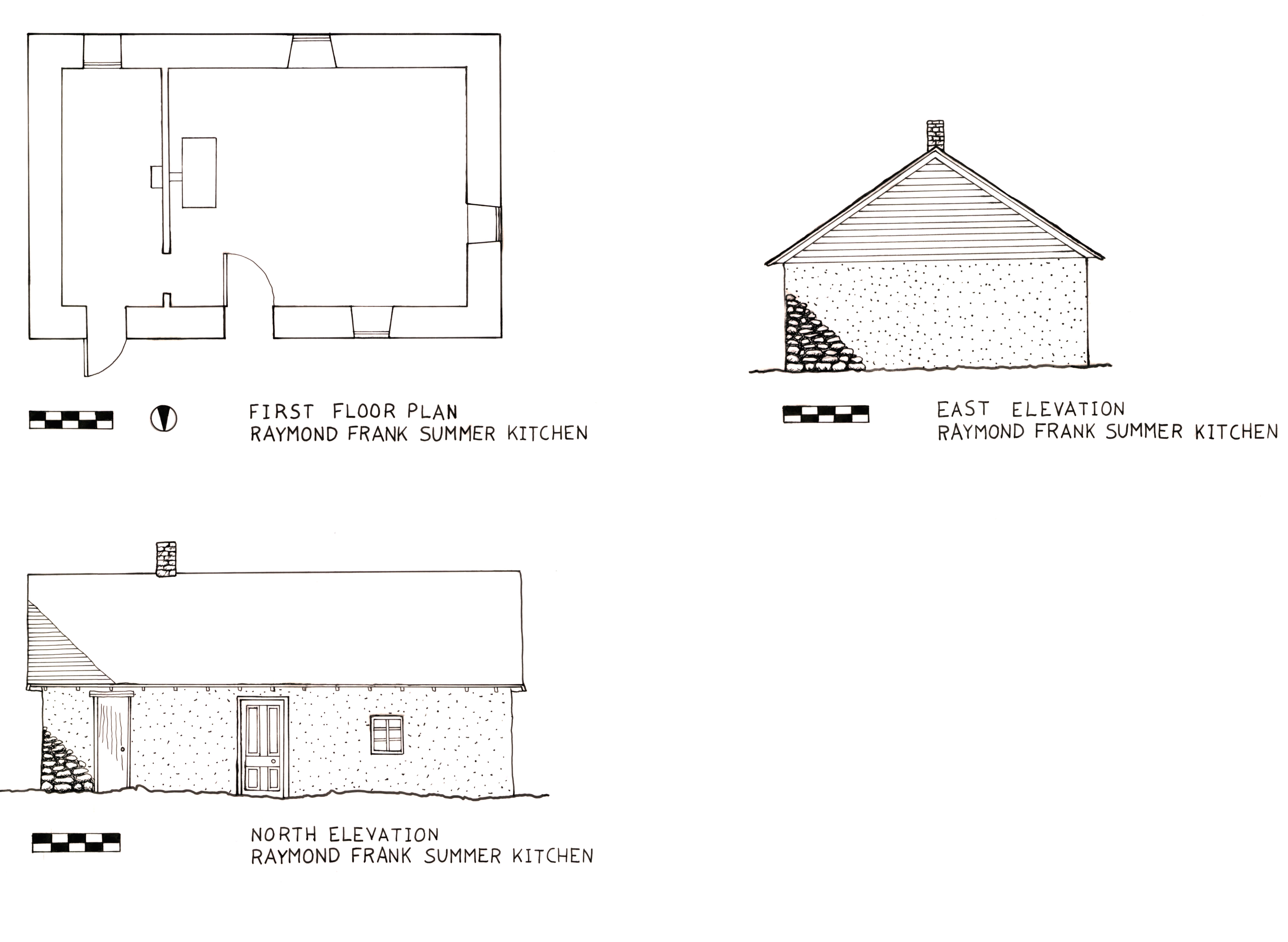

The original summer kitchen is a two-room rectangular building, located about 75 feet southeast of the historic house. Similarly to the previous buildings, it is also built of uncoursed stone clad in plaster. A wood-framed gable roof with wood shingles rests atop the stone walls. The end gables are covered with clapboard. The kitchen does not rest on a foundation and is thus settling into the ground, making the floors uneven and the building’s overall deterioration easily apparent. According to Jeff Frank, about one-foot of the original wall is now underground. Small four-light windows are located in the north, south, and west elevations (one on each side). The entry door, located on the north side, leads into the larger of two interior spaces, which is a kitchen/dining room area (west). A smaller storage room is located to the east of this space, separated from it by a board partition. This is one of the few historic summer kitchens surviving in the area and the oldest example among the properties in this study.

Other notable extant historic buildings on the farm are a historic root cellar, a privy, a garage, a granary, and two sheds. Modern buildings include a bungalow-style house (current residence), modern grain bins, and a modern machine shed.

The farmstead appears to have been built by Raymond Frank before 1914, as it appears on the 1914 Stark County Atlas.[6] Raymond was born in Russia, but had German as his native language as listed on the 1910 Census.[7] Raymond likely migrated sometime between 1900 and 1910 as he first appears on the Federal Census Rolls in 1910, at which point he is listed as living in Stark County.

Frank farmed his property through the 1940s, then apparently handed the farm over to his son, Sebastian. Sebastian lived at the farm with his family of six for several decades before passing it on to his son, Jacob. Currently Jacob’s widow, Florence, resides there with their son, Jeff Frank.

The Raymond Frank Farm, as one of the earliest farms we studied, offers us a nuanced insight into the folk building traditions brought by its original German-Russian settlers. The farm reflects an important moment in the history of the early twentieth century American frontier through the choices of building materials to architectural features and design. For instance, it shows how German-Russian builders applied their traditional building techniques using the materials native to North Dakota.

The relatively treeless and flat landscape of the prairie, much like what they found back in eastern Europe, meant limited access to wood building materials. Alternatively, then, builders used the resources indigenous to the area to erect their buildings. As a result, and unlike the more ephemeral sod structures commonly associated with Great Plains settlements, the historical buildings of the Frank Farm display the kind of sturdy clay and stone structures typical of the Black Sea region in Russia.[8] It is, therefore, not surprising that they have withstood over a century against the harsh winter weather found in North Dakota.

The relatively long and narrow, rectangular-shaped, two- or three-room end-to-end buildings with gabled roofs as seen in both the summer kitchen and the historic house also match their old world correlates. The 18-24 inches thick walls constructed to increase structural strength and to balance interior temperatures were also common in German-Russian folk architecture. But it is the wood-framed vestibule, or vorhäusl, extending off the facade of the historic house that stands in as quintessentially German-Russian.

The historical importance of the Raymond Frank Farm is undeniable. Together, its historical buildings provide a comprehensive, nearly complete, picture of the building traditions adopted by its early settlers. They are, however, more than just records of an immigrant community arriving in the US in later nineteenth and early twentieth century, they too reveal how such community–in all its tenacity, resourcefulness, and ingenuity–came to help shape an American identity.

Frank Ehlis Farm

–Laura Grotjan

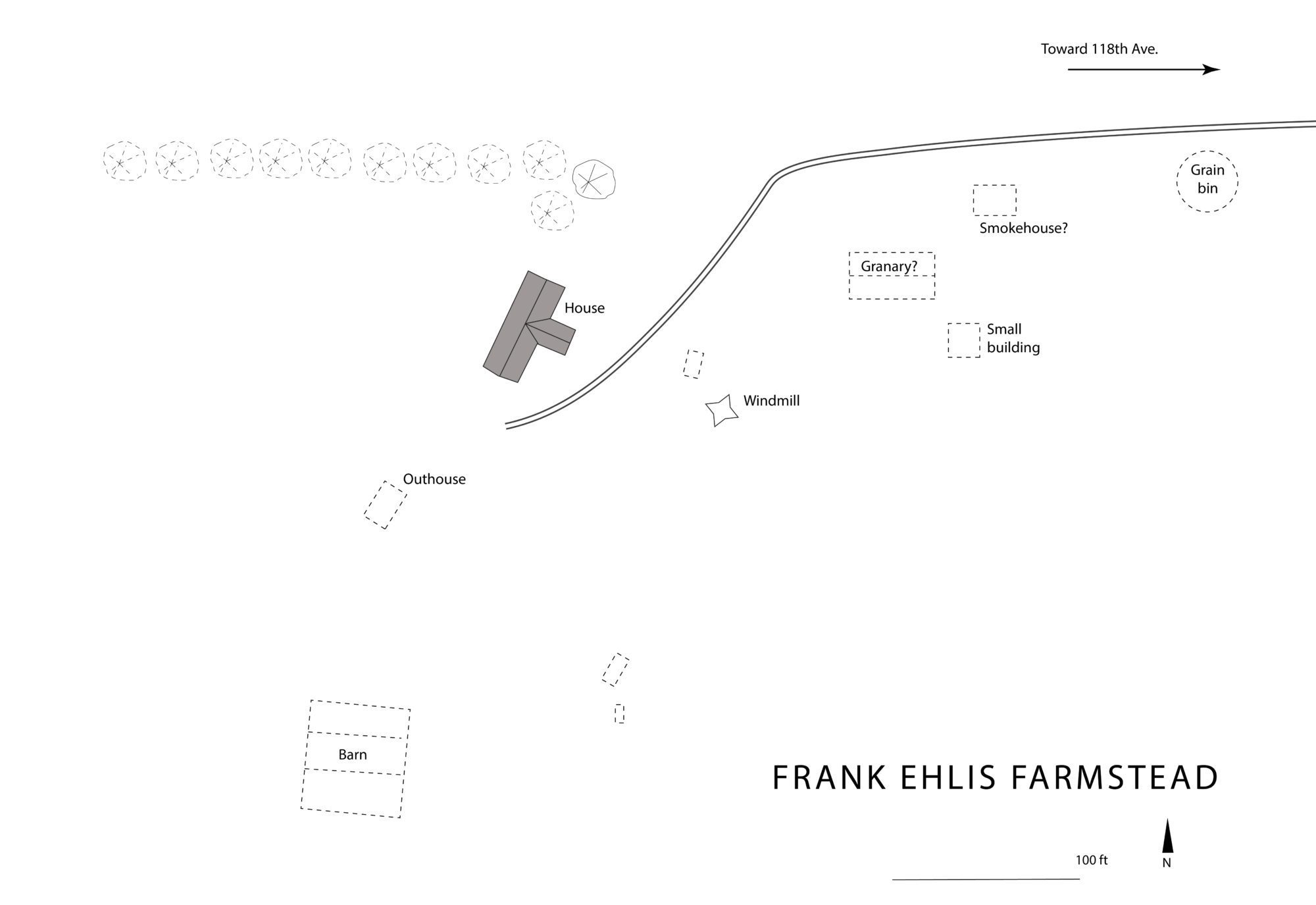

The Frank Ehlis Farm consists of an extant farmhouse surrounded by rolling fields (currently planted in wheat) located on the west side of 118th Avenue SW, approximately 0.25 miles west of its intersection with 53rd Street SW. The farmstead was originally arranged in an L-shaped plan, and would have included numerous outbuildings, such as a barn, granary, grain bin, outhouse, windmill, and smokehouse. All that remains is the early twentieth-century house.

The one-story, gable-roofed farmhouse faces southeast. It is three rooms wide, and has an attached summer kitchen on the northeast end of the building. The summer kitchen is only accessible through an exterior door. The house includes a projecting gable ell which creates a T-shaped footprint. Exterior and interior walls are made of uncoursed rubble stone, and the interior walls are coated in stucco and were once painted red and light blue. According to George Ehlis, the room adjacent to the summer kitchen originally had a dirt floor.[9] The walls of the summer kitchen have mostly collapsed, although the rest of the house has been recently pointed up with cement. A significant amount of the interior has also been patched with cement. Additional contemporary updates include an asphalt shingle roof and 4/4 windows.

The farmhouse was likely built in 1906 when the earliest owner, Frank Ehlis (1872-1928), immigrated from Russia. His native language is listed as German in the 1910 census, his occupation is recorded as farmer, and he is said to own his farm.[10] As of 1975, the farm is referred to as the Tony Ehlis farm, implying that Frank’s son Anthony (1912-1985) must have next taken over the farm.[11] Presently, the house is owned by Frank Ehlis’s grandson (Anthony’s nephew), George Ehlis, who lives on the nearby Daniel Ehlis farmstead and whose family crops the land surrounding the Frank Ehlis house.

The Frank Ehlis house shares multiple characteristics with “typical” German-Russian houses. The house follows a linear plan and has the quintessential vorhäusl, which complies with the Russian tradition of using an antechamber or entryway.[12] However, the vorhäusl does not function solely as an entryway in the Frank Ehlis house, but rather as a kitchen. It is possible that a partition may have been used to create an entryway within the kitchen, as William Sherman mentions was sometimes practiced.[13] Additionally, the summer kitchen is not a separate building, as is usually the case, but is instead abutted to the northeastern end of the house.

The simplicity of the Frank Ehlis house in comparison with the neighboring Daniel Ehlis house, an early twentieth-century frame bungalow, is reflected in George Ehlis’s oral history describing their contrasting personalities. Daniel is described as a well-to-do man who valued quality and investment, while Frank had simpler taste and was more interested in occasional frivolity with his family.[14] The houses also reflect different ways in which the Germans from Russia adjusted to life on the American frontier, some preserving old world ways while others more quickly adapted to early twentieth-century American ideals.

Clemens Steier Farm

–Michelle Prestholt

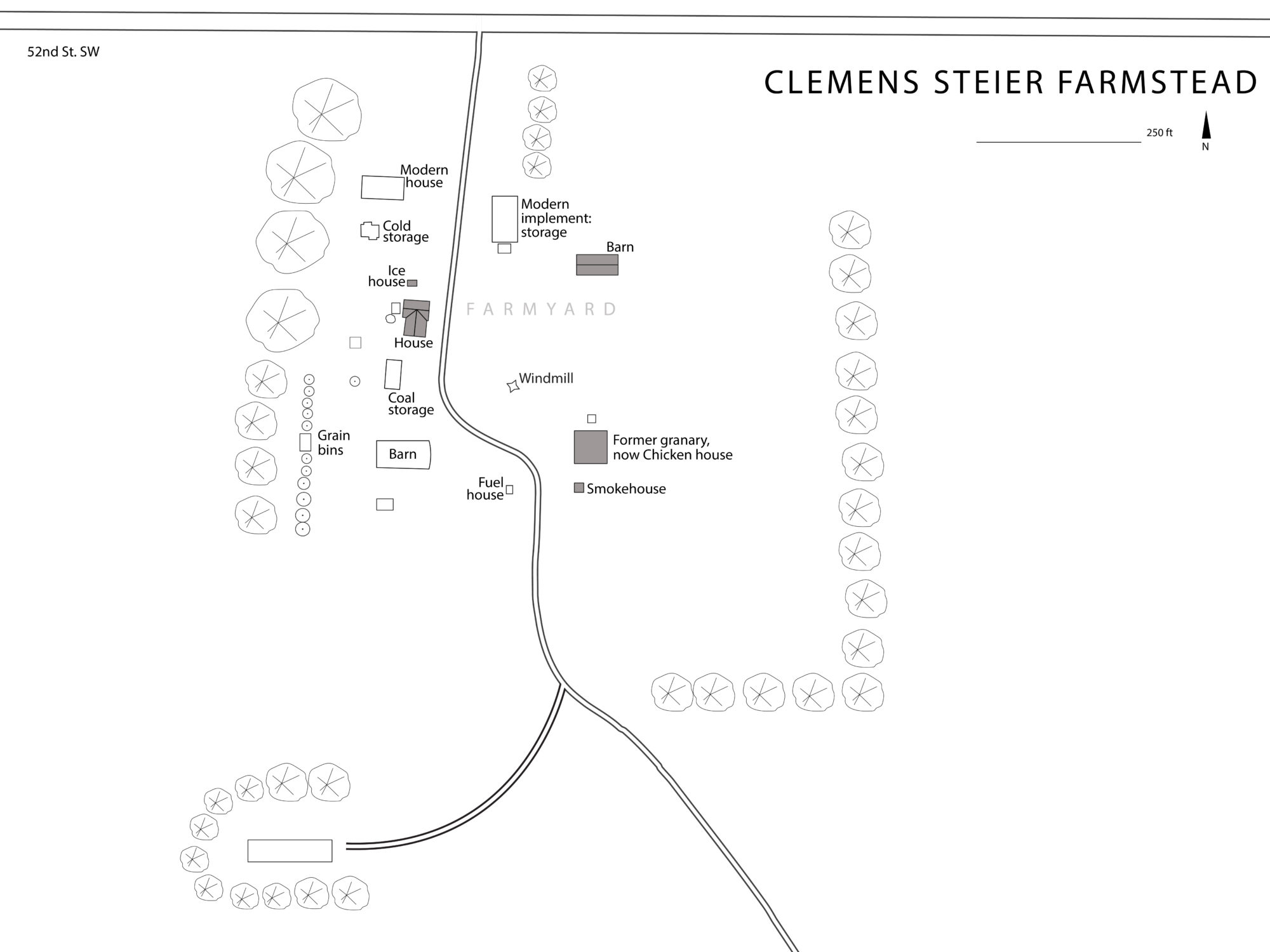

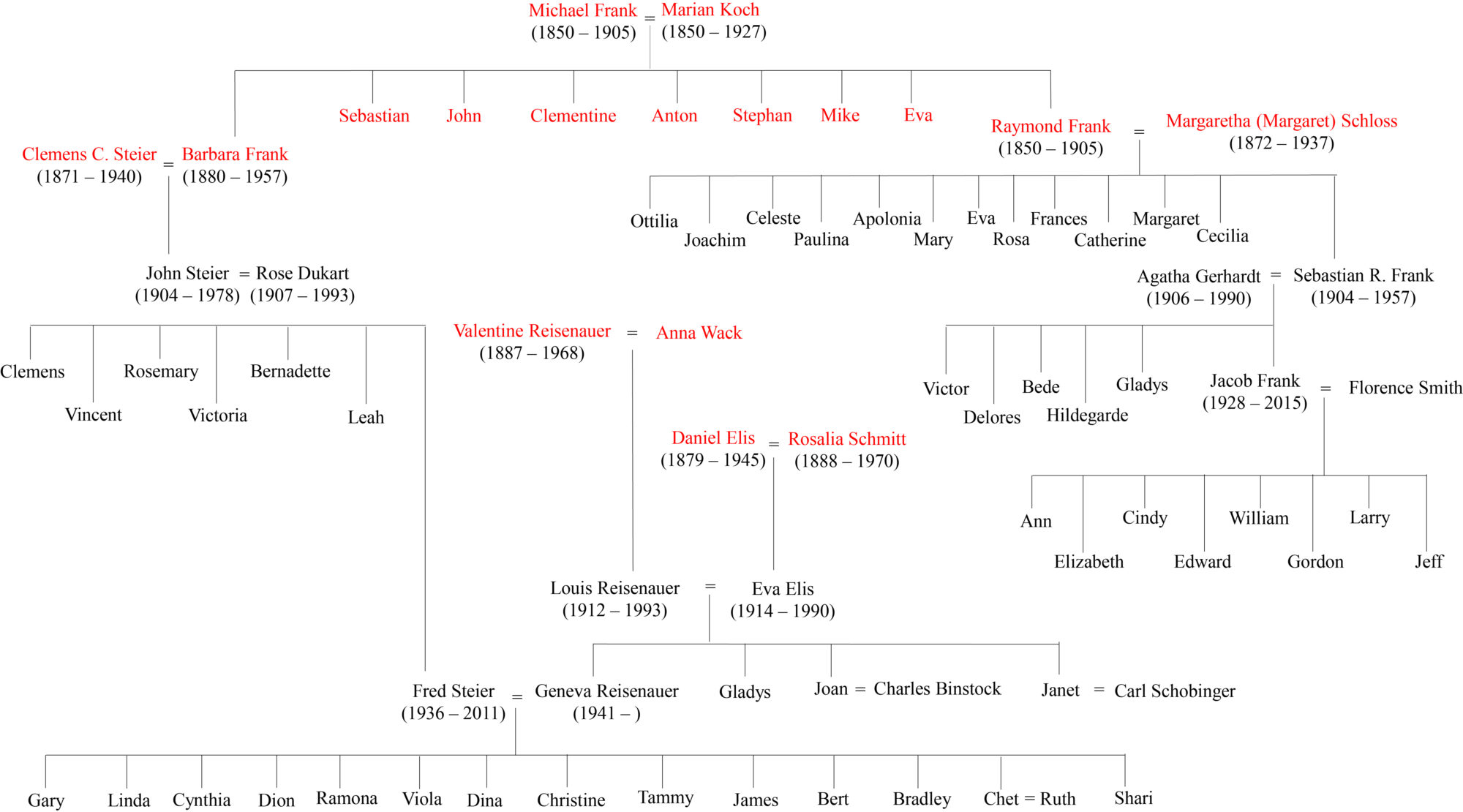

The Clemens Steier Farm contains an assortment of farm buildings, both modern and historic, and is located on the south side of 52nd Street SW about one-half mile east of Highway 22. There are three historic buildings dating to around or after 1910 made from stone: a farmhouse, barn, and smokehouse, as well as numerous other farm buildings. The farmstead is arranged in a courtyard style, with a large, open farmyard between the house and the barn.

The historic buildings were constructed by Clemens C. Steier, a “German from Russia,” who immigrated from Landau, Odessa, Russia (present day Ukraine) to North Dakota in 1892. He married Barbara Frank, also from Landau, in 1901. He purchased 320 acres of land seventeen miles south of Dickinson under the 1820 land purchase act on July 18, 1910.[15] Two miles north of that plot, Clemens acquired 640 acres from the railroad the land on which the current farmstead is situated and referred to it as “Ranch Place.”[16] All of the masonry buildings on the modern farmstead were built using stones that Clemens moved from the southern plot.

Clemens and Barbara moved into Dickinson after John’s marriage to Rose Dukart in 1926. In 1963, John and Rose moved into the same house in town, leaving management of the farmstead to their youngest son, Fred, and his new wife, Geneva Reisenauer. Geneva continues to live in the stone house on the farm today, with her and Fred’s second youngest son, Chet, managing the farm.[17]

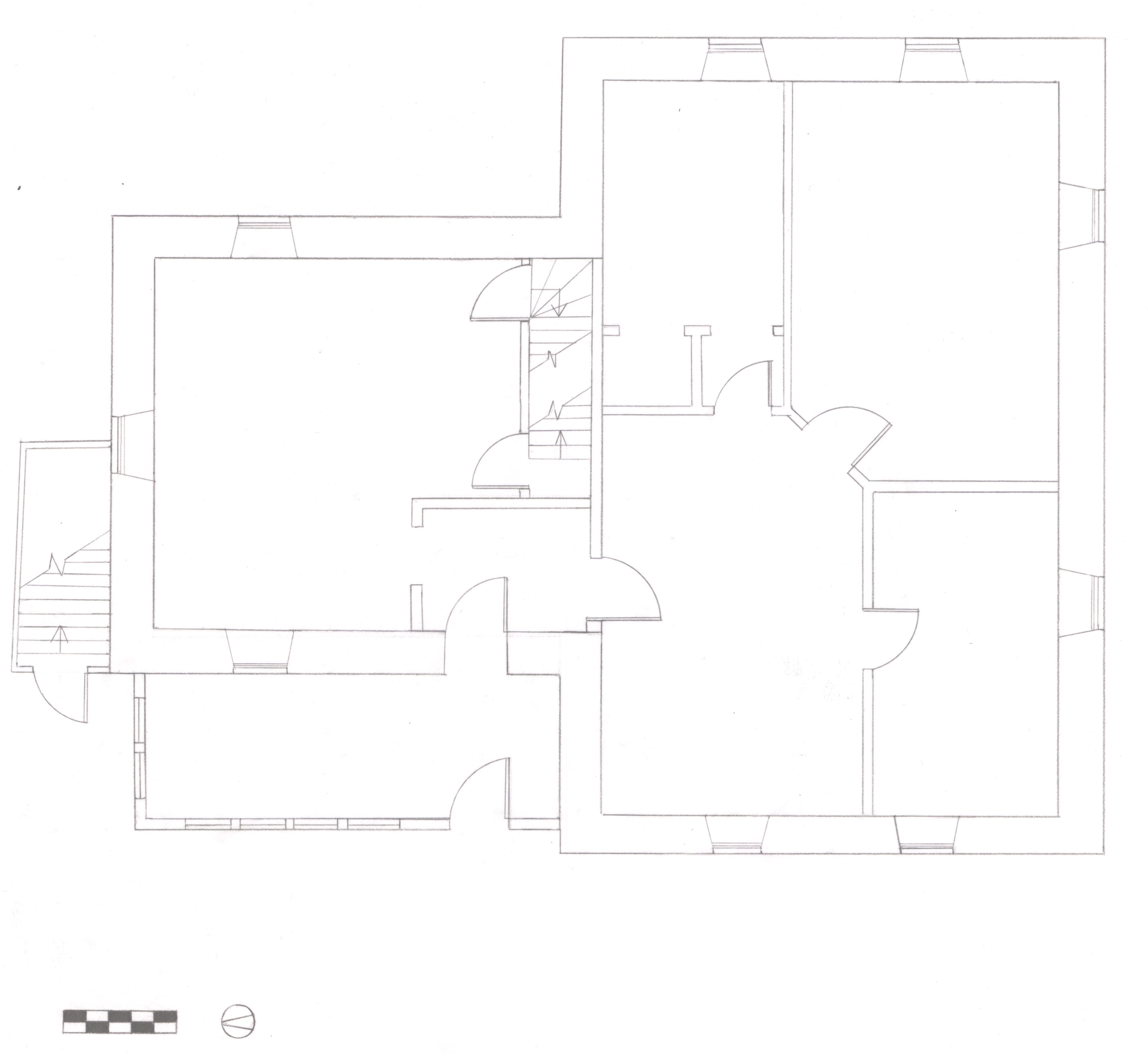

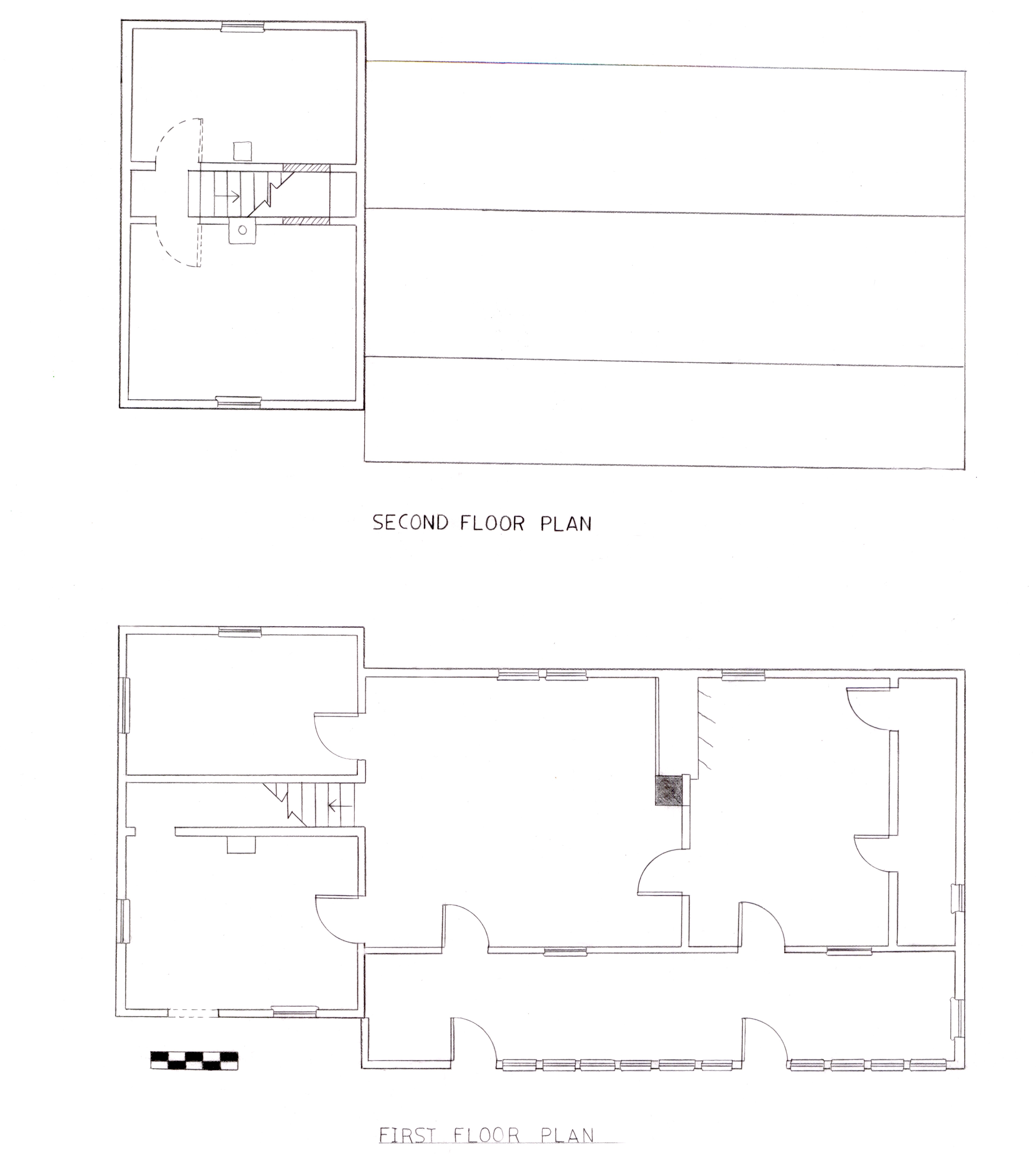

The historic house is set back from the road on the western half of the farmstead. Built of masonry and covered in plaster, it stands two-stories in height and has a gabled roof. Family history affirms that the house was finished in 1910.[18]

The house has a “T-plan” and the northern wing is double pile. The kitchen wing forms the ‘T.’ Historically, there were two bedrooms on the first floor, with two sitting rooms. There were two bedrooms on the second floor, with an abundance of attic storage space. One of the bedrooms on the first floor of the historic stone home was transformed into a bathroom in 2010.[19] The dwelling has been continually inhabited since its construction. It was an ambitious plan for its time in the area in terms of its size and form. The porch was initially uncovered but was roofed sometime before the 1950’s. Currently there is a second home on the property located closer to 52nd Street SW.

The historic home has an intricate basement level as well, whose footprint is well beyond the first floor of the house. There is a furnace room, a room for cooking and cleaning, a bathroom, a canning room, and cold storage. There are two access points, one outdoors from the farmyard and one from inside the kitchen on the first floor of the home. There was a well that is still operational, but no longer in use. Modern appliances, including refrigerators and stoves, were added before the 1950’s.

The barn is located to the east of the house across an open farmyard. It is made from the same rubble stone as the home and is topped by a Gothic arched roof. It was constructed after the house was completed, sometime after 1910. The upper level is used as a hay loft. The lower level is divided into pens for livestock. The roof burned in 1959, at which time Fred and Chet lowered the walls around four feet and rebuilt the frame roof.[20]

Other historical buildings include a smokehouse, an icehouse, and a granary. The smokehouse is located to the southeast of the house. All of the working farm buildings are situated on the eastern part of the farmstead while the domestic spaces, including outbuildings like the root cellar and icehouse, are on the western side. The family butchered their own meat (chicken and pig) and continues to do so. The granary may have been the first building constructed on the property and used as the earliest domestic space.[21] According to family tradition, Clemens, Barbara, and their only surviving son, John, lived in a smaller building with a lean-to for a chicken coop during the construction of the larger home. This building became a granary upon the completion of the main house.[22] A windmill from the 1920s stands in the open farmyard.

A. Jirges Farm

–LauraLee Brott (with Anna Andrzejewski)

The A. Jirges Farm is located in Hettinger County, just south of the Stark County line. The farmstead consists of six buildings and structures of varying condition arranged in a “courtyard” layout, with the house, barn, smokehouse, cellar, and chicken coop creating a rim around fairly large open farmyard in the center. The only structure that breaks up the open space is a small windmill.[23]

The abandoned farmstead is nestled within the farm fields and accessed off a long driveway, which extends eastward off the main road (118th Avenue). The farmstead is situated in the lowest part of the farm, to the north of a hill that slopes upward about sixty feet. This hill provides a view of the whole farm, including the pond that is now dry that sits in the middle of a rectangular shaped shelterbelt directly to the west of the structure.[24]

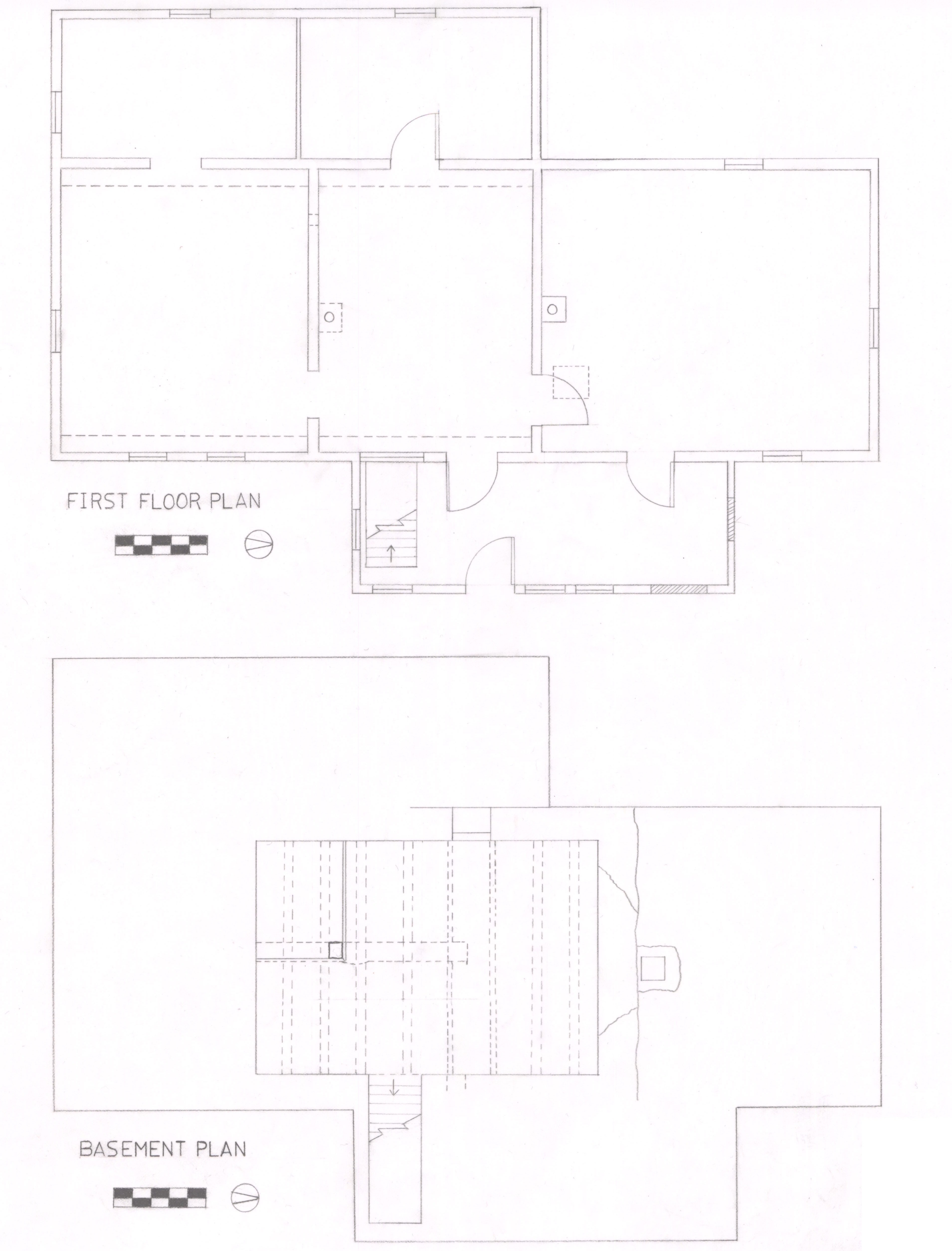

The historic house is of wood frame construction, and rests on a stone foundation. It consists of two main sections: a two-story, two-room per floor “upright” and a one-story cross wing. It is possible the upright and wing may have been built in two phases, with the upright followed shortly after by the wing. The wing is made up of a large central common room, and a kitchen (on the north side of the structure). A porch addition spans the length of the cross wing. Both the upright and wing were capped with gabled roofs; the porch has a shed roof.

Apart from a ghost door visible on the eastern façade, there are a few clues to indicate a two-phase construction sequence. The interior of the structure is more revealing in terms of building phases, specifically in the second story of the upright, or southern portion of the structure. There, two ghost doors are sealed in, the frames of which were used for the newer bedroom doors (one of the older door frames was cut at an angle that matches the roof angle which intersects with the wall). What is most peculiar about these ghost doors is that they currently lead to a drop (the staircase runs in the opposite direction). Close inspection in the first floor closet space revealed that the stairs may have initially run the opposite direction, and at some point, were may have been switched to accommodate for the construction of the cross wing.

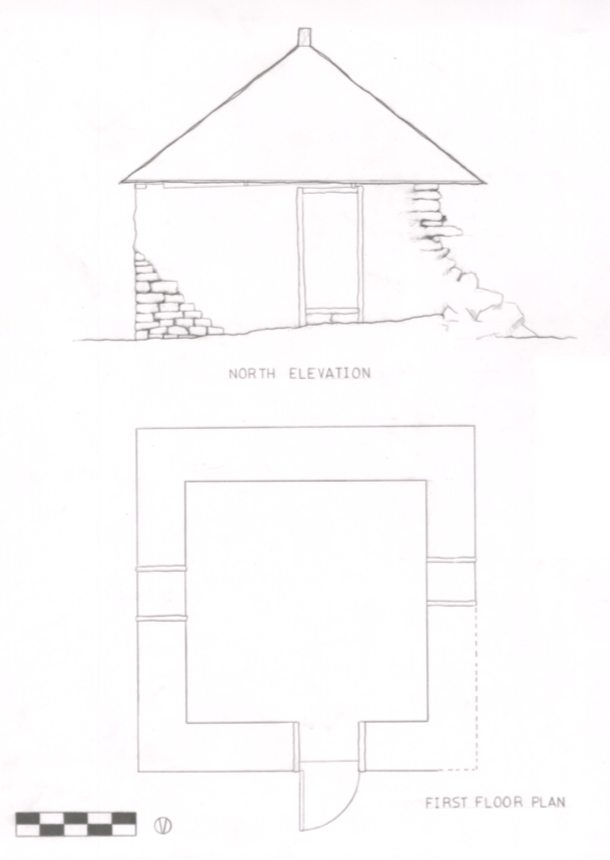

East of the house is a historic barn, dating to roughly the same time period as the house. The barn has fallen into disrepair, with the upper story frame section and roof collapsing, with parts scattered across the fields and barnyard.[25] Originally, the barn had a stone ground story and a frame gambrel roof. The smokehouse, cellar and chicken coop are smaller square planned structures. The stone smokehouse has a pyramid-hip roof, and has retained much of its original shape, but the western corner of the northern wall is crumbling. The door is in the center of the north wall. The root cellar had a front-gambrel roof, and is almost completely destroyed because it was built with a wood frame. The gambrel roofed chicken coop, also made of wood frame, is still standing. The portal is in the center of the west wall and faces the house, likely for ease of access for the home owners.

The house post-dates 1917, as it does not appear on the Hettinger County atlas. At the time of the Atlas, the land belonged to Anna Bernauer, the widow of Jakob Bernauer.[26] The Bernauers immigrated to Chicago from Hungary in 1902 and to North Dakota in 1906.[27] Although Jakob died in 1907, Anna staked claim to the land where she lived with her daughter, Elizabeth, and her husband, Joseph Hoffman.[28] Joseph died in 1916, after which Elizabeth married Anton Kipp in 1918. Kipp was also a German from Hungary.[29]

The Kipps probably built the current house on the A. Jirges Property shortly after their marriage in 1918. [30] This date makes sense in terms of the house type, the upright and wing, which was a popular house type from the late nineteenth into the early twentieth centuries. This type is characterized by having a gabled two-storied section – the “upright” – adjacent to a one-story wing.[31] Although this house form could be built in any material, frame construction was the overwhelmingly popular choice for most examples by the 1900s. This was because by this point, dimension cut lumber was readily available and made the form easy to construct.

The A. Jirges Farmstead makes an interesting comparison with others in the project area. While the outbuildings compare with others built by Germans from Russia in the project area, the house is something entirely different. It is built of wood versus stone (stone being the most common building material for many of the first permanent houses of the Germans from Russia). Moreover, the house is a common American vernacular form widely found amongst many groups across the nation, especially the Midwest, during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, not the linear one-story vernacular form typically seen with German-Russian immigrants.

While the house material and form may be explained by the later date of the house, it also may have to do with the fact that by the time it was built, immigrants to the region were already adapting to life on the prairie. This was the second house built by Anton Kipp, for his second wife, Elizabeth, and their children (from previous marriages). By this point, lumber was more readily available, but more significantly, immigrants like the Bernauers, Hoffmans, and Kipps were adopting new lifestyles, of which new ways of building are one example. Old world ways were giving way to the new just as the settlers themselves were increasing their wealth such that they could buy new materials (such as lumber) rather than relying on the stone from their fields.

Yet the history of this property is also interesting as the only example with a known connection to the Germans from Hungary. As discussed in Chapter 4, Germans from Hungary were also in the vicinity of St. Pius. While they worshipped elsewhere (Elizabeth is buried at St. Mary’s in New England and her father, Jakob Bernauer, is buried at St. Elizabeth’s in Lefor), they lived in close proximity to their Germans from Russia neighbors. It is also intriguing that the outbuildings on this property were built and look similar to their Germans from Russia counterparts.

The A. Jirges farmstead thus raises many questions that could guide further research efforts in this area. How quickly did ethnic groups acculturate to life on the prairie and how is this reflected in their buildings? Also how similar were the building techniques of Germans from Russia and Germans from Hungary? And how does that relate to building practices from Europe and Russia generally?

Frank D. Weiler Farm

–Travis Olson

The Frank D. Weiler Farm is located one-half mile west of the intersection of State Highway 22 and 52nd Street, approximately 2.7 miles southeast of the Town of Schefield in Stark County, North Dakota. Historic aerials reveal that the farmstead once contained at least nine buildings arranged in a courtyard plan, but only three of these buildings remain: a dwelling, a machine shed, and the ruins of a barn.

Frank Weiler was born April 12, 1886 in Katherinental, South Russia, the youngest of five children.[32] He came to North Dakota in 1902 where he worked as a farm hand, first on his brother-in-law, Joseph Dukart’s farm and then on a farm south of New England. In 1906 he established a farm of his own.[33] The first house on the site was built of sod and rock, and it’s possible the cellar of the current house dates to this initial construction. In 1907 Frank married Catherine Urlacher, and between 1908 and 1934 the couple had eleven children.

The current house was likely built ca. 1910 as a two-room, single-story, balloon-frame construction with a side gable roof on a stone foundation. The house has had three additions: a shed-roof addition to the rear (west) elevation; a single-story, gabled kitchen addition to the side (north) elevation; and a shed-roof, enclosed-porch addition to the front (east) elevation. The walls of the house are covered in horizontal wood sheathing and then faced with clapboard, except the front (east) elevation where the walls were faced with drop siding and later covered with asphalt shingles patterned to look like brick. The house contained wood, two-over-two, double-hung windows throughout, but many of the windows are broken or missing. The side-gabled roof is faced with wood shingles and contains two interior chimneys; the southern chimney is made of brick and is located at the approximate center of the main wing, and the northern chimney is concrete block and marks the beginning of the northern addition.

The main block of the house contains a partial basement, located under the northern of the two rooms, accessed by a bulkhead entrance incorporated into the porch addition. The basement contains a dirt floor and stone walls, and a hewn summer beam (likely the remnant of an earlier structure) runs across the ceiling. The dwelling’s first floor is divided into six rooms. Of the two rooms that constitute the main block of the house, the northern room appears to have been the finer of the two. While both rooms contain wide baseboard, the northern room also retains crown molding. A stack chimney projects into the northern room, signaling the location of the stove. The rear shed addition also contains two rooms, one accessible from each room of the main block of the house. The kitchen addition contains a single room with a concrete block chimney at its southern end, and a trap door in the ceiling leading to a shallow attic. The front addition was likely built as an enclosed-porch (or vestibule) addition, and contains a single room which opens to both the northern room of the main block and the kitchen addition.

The Weiler dwelling shares many characteristics with the other German-Russian houses in the region, including the linear three-room plan, partial cellar, thick stone foundation, and enclosed entrance space (or vorhäusl).[34] However, this house is distinctive among the other extant German-Russian houses in the area because of its somewhat diminished scale, and because it is a unique example of early twentieth century German-Russian frame construction in the region.

- Two of the seven farms - the K. Steier Farm and the Daniel Ehlis Farm - were not researched in enough detail to warrant inclusion here. ↵

- William C. Sherman, "Prairie Architecture of the Russian-German Settlements in the United States," in Russian-German Settlements in the United States, ed. Richard Sallet (Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1975), 187. ↵

- Sherman, "Prairie Architecture of the Russian-German Settlements," 186. ↵

- NDCRS Architectural Site Form, Feature #2, page 2. ↵

- NDCRS Architectural Site Form, Feature #9, page 2. ↵

- George A. Ogle and Co., Standard Atlas of Stark County, North Dakota (Chicago: Geo. A. Ogle and Co., 1914). ↵

- Schedule of Population, U.S. Census, 1910. ↵

- The historic buildings on the Raymond Frank Farm are made of uncoursed stones plowed from the nearby fields and clad in white clay plaster. For further discussion, see Dell Upton, ed., America’s Architectural Roots: Ethnic Groups That Built America (New York: John Wiley, 1995), 131. ↵

- George Ehlis, Pers. Comm., June 29, 2017. ↵

- Schedule of Population, U.S. Census, 1910. ↵

- See http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org. ↵

- William C. Sherman, “Prairie Architecture of the Russian-German Settlements,” in Russian-German Settlements in the United States, ed. Richard Sallet (Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1975), 187. ↵

- Sherman, “Prairie Architecture of the Russian-German Settlements,” 187. ↵

- George Ehlis, Pers. Comm., June 29, 2017. ↵

- Patent Accession Number 145037, U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. ↵

- Betty Gardner and Eleanor Olson, New England Centennial 1886-1986: Century of Change (New England: Richtman’s Printing, 1986), 547. ↵

- Geneva Steier, Pers. Comm., June 27, 2017. ↵

- Geneva Steier, Pers. Comm., June 27, 2017. ↵

- Geneva Steier, Pers. Comm., June 27, 2017. ↵

- Gardner and Olson, New England Centennial, 548. ↵

- Geneva Steier, Pers. Comm., June 27, 2017. ↵

- Geneva Steier, Pers. Comm., June 27, 2017. ↵

- An aerial from 1952 shows three additional structures northwest of the current farm, just north of the shelter belt that surrounds the ghost pond. ↵

- The pond is indicated in a topographic map from 1973. ↵

- According to the current owner, the barn collapsed in a windstorm. It was intact in 2016, so the damage occurred only in the last year. A. Jirges, Pers. Comm., June, 2017. ↵

- George A. Ogle and Co., Standard Atlas of Hettinger County, North Dakota. Chicago: Geo. A. Ogle and Co., 1917 ↵

- “Elizabeth Bernauer Kipp” (obituary), https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/76667288. ↵

- North Dakota Naturalization Index, 1874-1963, P08, 38 (Hettinger County). ↵

- U.S. Census, Schedules of Population, 1910 and 1920 list Kipp’s birthplace as Hungary. ↵

- “Elizabeth Bernauer Kipp” (obituary), https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/76667288. Assessment records in the Hettinger County Courthouse also reveal a jump in property value in 1918-19, which suggests improvements on the property at that time. ↵

- See Fred W. Peterson, Homes in the Heartland: Balloon Frame Farmhouses of the Upper Midwest, (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 30, 109-11. ↵

- Gardner and Olson, New England Centennial, 588. ↵

- Gardner and Olson, New England Centennial, 588. ↵

- William C. Sherman, “Prairie Architecture of the Russian-German Settlements,” in Russian-German Settlements in the United States, ed. Richard Sallet (Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1975), 187. ↵