8 Stories in Stone (and Earth)

Investigating Buildings in Southwestern North Dakota, Fall 2018

Anna Andrzejewski

Our investigations led us to questions about place – but they grew out of a close look at the buildings and cultural landscape. As explained in Folk Farmsteads on the Frontier and as Ahmed Abdelazim discussed in an earlier chapter, our methods begin with closely looking at the physical fabric. Doing so offers a point of entry of sorts. We learn about materials and building technology, to be sure, but we also learn about cultural changes over time, gender relations, social patterns of behavior, and individuals’ relationship to the natural world – just to name a few things this group was interested in.

It’s a truism of sorts in the study of vernacular architecture: buildings raise questions but rarely answer them. Nowhere is this more true than in the sites we studied during this fieldschool. We want to the field this trip with two aims: first, to finish some sites we had looked at previously; and second, to expand on the kinds of sites we looked at in 2017. It is the new sites we explored are the subject of this chapter.

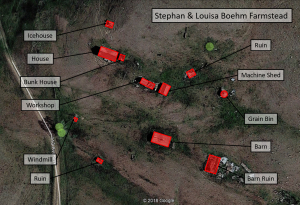

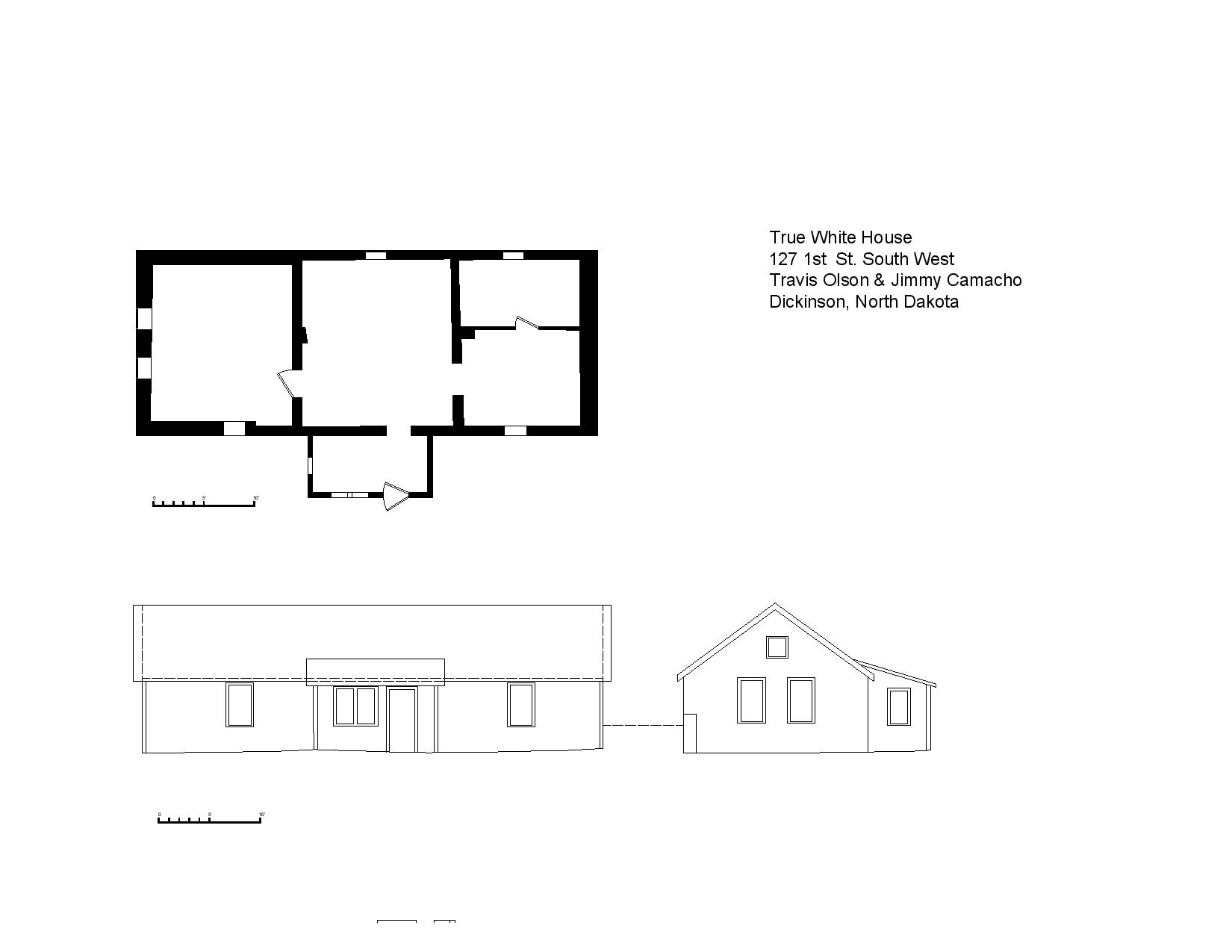

Our choices about what we studied were dictated partly by access. We had been granted permission to look at three sites – the Nick and Eva Hecker Farm, the Sebastian and Anna Frank Farm, and the Jacob and Helena Wandler Farm – near Schefield, which allowed us to expand on our previous year’s findings. Another property – the Stephan and Louisa Boehm Farm – was made available to us by Peter Betchner, who had fond memories of the site of his great aunt’s family’s farmstead. And a site in Dickinson – 127 First Street SW – was offered to us as an example of a pioneer urban house, and one in another building material: earth.

While these sites were made available to us by word of mouth, the collection allowed us to draw some interesting conclusions that built on our work of last year while also raising new questions the UW team hopes to explore in the future.

Germans-from-Russia Diversity

Our field investigations in 2017 were constrained by limits of a project area as well as focused on “Germans from Russia.” Armed with reading the key sources on the architecture of this ethnic group, we were not surprised when we went into the field to find examples of linear rock houses associated with this group. The Raymond Frank Farm, in particular, was a classic example of the sort William Sherman and Alvar Caarlson had identified in the region. We certainly saw evidence of what might be called acculturation in some farmsteads (such as the Clemens Steier and Frank Weiler Farms), but our findings in some ways supported, versus challenged, the few previous investigations of the region’s folk architecture.

Much to our surprise and delight, field investigations of houses associated with Germans from Russia this year revealed more variety. Whereas last year we saw evidence of variety in building materials (frame versus stone) and in second- and third-generation buildings, this year we saw early houses with different, non-linear plans. The houses on the Wandler-Binstock Farm and the Sebastian and Anna Frank Farm are both double pile (two room deep) houses. Both of which diverge from William Sherman’s typical double pile plan.

This year’s study houses thus raise questions we hope to answer through further fieldwork – namely:

- What led pioneers to choose one plan over another?

- How much variation is there in Germans from Russia houses?

- How do plans of Germans from Russia houses compare with that of other immigrant groups (such as the Germans from Hungary)?

Germans from Hungary

This year’s trip offered the UW team its first chance to explore a farm built by Germans from Hungary. The house on the Stephan Boehm farm compared in its linear plan with the houses we had seen by Germans from Russia. This has prompted questions about the association of the linear plan with German-Russians, asking if it is instead a regional versus ethnic form. The location of the Boehm Farm, just south of the Stark County line in Hettinger County, also raises questions about boundaries. As an earlier chapter suggested, residents recall a firm line between German-Russians and German-Hungarian settlement – but where precisely that line is remains an open question.

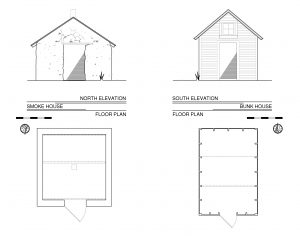

The Boehm Farm also had a “bunkhouse” – something we also saw at the Nick and Eva Hecker Farm and in a driving tour near Lefor later in the week. According to Peter Betchner, this bunkhouse was used as sleeping space for male children on the farm. Its location adjacent to the house suggests a close association between the farmhouse and this outbuilding.

Barn Stories

Folk Farmsteads largely focused on domestic buildings, namely farmhouses. Although we photographed some of the large multi-purpose barns and drew some outbuildings in 2017, this year we paid much more attention to these buildings in hopes of drawing conclusions about agricultural practices in southwestern North Dakota. Our findings suggest much more work should be done to document these buildings, many of which stand in ruin or are being modified beyond recognition. We found barns to store horses (teams); barns for cattle; granaries; dairy buildings; summer kitchens; bunkhouses; and smokehouses. Teasing out the evolution of types of structures, their changing layout over time, and their construction will certainly yield a richer story of agricultural history in the region than has been told previously.

City-Country/Stone-Earth

Our fascination with buildings in the area is at one level borne out of our admiration for stonemasonry, particularly the survival of this hand-crafted mode of building from fieldstone culled from the prairie in the twentieth century (a time when most of the country was building in mass-produced materials using plan or kit houses). Yet oral evidence survives to tell us that stone was only one of many building materials used by eastern immigrants on the Great Plains. Stories of sod dugouts and sod houses abound, yet we know they are not inclined to survive.[1]

An opportune phone call from a Dickinson resident just prior to our trip to the field led us to a house in the county seat we had reason to believe was sod, 127 First Street SW. Field investigation and discussion with the owner suggested it was “rammed earth” (versus sod), but that in itself is significant and raises many questions we hope to investigate in later studies.

- Was there a difference between “urban” and “rural” building methods in the period of pioneer settlement (late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries)?

- What exactly is this method of construction (the White House was inconclusive as to how it was built because of its continued occupancy)?

- Who lived in houses like this, why, and for how long?

- What is the relationship between “urban” and rural life in southwestern North Dakota?

We hope to hold a future fieldschool class focused on south Dickinson, where it appears some other examples of this type of house still stand.

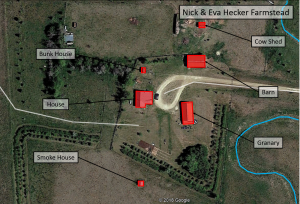

The Nick and Eva Hecker Farm

TRAVIS OLSON

Our field investigations in 2017 introduced us to the ethnic architecture of the German-Russian immigrants who began to settle the area around what would become Schefield around the turn of the twentieth century. Many of the farmhouses that we investigated then, including those located on the Raymond and Margaretha Frank Farmstead, the Frank Ehlis Farmstead, and the Frank and Katharina Weiler Farmstead followed the architectural precedents identified by historians such as William Sherman and Alvar Carlson—namely linear single-pile (one room deep) homes, typically two or three rooms wide, and often with an enclosed entrance vestibule called a vorhausl.[2] In 2018, our research both affirmed and complicated this understanding of German-Russian houses in Western North Dakota’s Stark and Hettinger Counties.

The Nick and Eva Hecker Farm, in many ways, follows the same model. The farmhouse is approximately forty feet wide and twenty feet deep of stone construction. The house has an addition, measuring roughly fourteen-and-a-half feet by sixteen feet, likely built in the early twentieth century, which extends perpendicularly from the front of the house—forming a T-shaped plan. A second addition, built of frame construction in the late twentieth-century, brings the house to its current configuration.

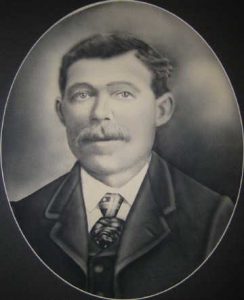

The house was built by Nikodemus (Nick) Hecker, who was born in Russia to parents Jakob and Ottilia Hecker. In 1898, Jakob, Ottilia and their seven children left Russia for Munich, then travelled to Hamburg where they boarded the SS Bulgaria for America, arriving at Ellis Island.[3] The ship manifest notes that Jakob and Ottilia’s destination was with his brother, Joseph Hecker, who was living in St. Paul, Minnesota.[4] Nick was fifteen years old. By 1900, Jakob Hecker’s family was listed in the federal census in Dickinson, North Dakota. Jakob was listed as a day laborer, as were his two oldest sons, Ludwig (eighteen at the time) and Nikodemus (who was seventeen).[5] Jakob Hecker homesteaded on 160 acres in Section 14 of Township 137N Range 97W by 1903, and within three years Nick homesteaded on 160 acres approximately two miles southwest of his father.[6]

According to the current property owners, the first stone building that Nick built on the farmstead is the granary, the building now utilized as a garage. That building initially served as house, barn, and granary—housing Nick, his livestock, and his first crop. It’s possible that Nick built a sod house on the property the year he claimed his homestead, to fulfill the requirements of the Homestead Act, but because Nick’s father lived nearby, and because we don’t know where he was employed as a laborer, it is possible that he forewent the sod house and immediately began work on the stone granary, particularly if it was built as a sort of housebarn. Around 1909, Nick married Eva Frank, daughter of Michael and Marianna Frank who lived on the adjacent farm, and by 1910, Eva had given birth to their first child, Anton Hecker.

We have yet to discover what fully became of Nick and Eva’s family after 1911—the year that Nick patented the homestead. Nick and Eva’s family is absent from the 1920 Census in Stark County, and it seems that the family moved to Oregon (where their second son, Michael, was born) then to California. In the 1920 census, a Russian-born Nick Hecker, of the correct age, was working at a shipyard in Oakland.[7] Eva appears in the same census as an inmate at the Napa State Hospital, and Anton appears to be a boarder at the California School for the Deaf and Blind.[8] In the 1930 census, Anton Hecker reappears in Stark County as a laborer on his uncle Michael Frank’s farm, and he is similarly employed in the 1940 census.[9]

The farmstead as it exists today is a fairly remarkable cluster of buildings, and tracing the deed of the property will help clarify the history of the farmstead. In addition to the house and the granary, the farmstead contains a stone barn with a low gable roof (therefore without a hayloft), unlike any of the barns that we’ve seen in the area so far. The property also contains a frame bunkhouse and a stone smokehouse—both building types that we’ve become increasingly interested in.

In 2017 we spent a short amount of time documenting the farmstead. As the house and the granary have both undergone significant interior alterations, we focused our efforts on gathering the property’s site plan and more detailed documentation of the smaller outbuildings.

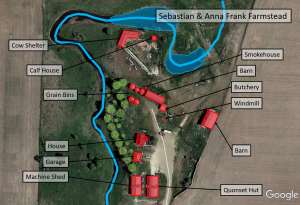

The Sebastian and Anna Frank Farm

TRAVIS OLSON

Eva’s brother Sebastian Frank and his wife Anna homesteaded the farm immediately south of Nick and Eva Hecker’s. Today nine buildings remain on the farmstead, four of which date from the first half of the twentieth century: a farmhouse, a butchery, two barns, and an Aermotor windmill. The farmstead also contains a collection of postwar structures, including: a garage, a Quonset, a machine shed, a cow shelter, a smokehouse, and five corrugated metal grain bins.

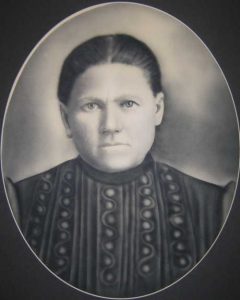

Sebastian Frank (1882-1959) was born in Landau, Russia (now Shyrokolanivka, Ukraine) to Michael and Marianna Frank. In 1898, Michael and Marianna Frank and eight of their nine children (their eldest son Stephen had emigrated with his uncles a few months earlier) sailed from Bremen to America, arriving in Dickinson, North Dakota on November 27.[10] The following year, Michael and Marianna claimed their homestead approximately fifteen miles south and one mile east of the City of Dickinson. One-by-one, Michael and Marianna’s children claimed homesteads on the land adjacent to the family’s sheep ranch, including Sebastian, who in 1904 claimed his farmstead approximately a mile west of his father’s. The following year, Sebastian married Anna Klein, a woman of German- Russian descent who immigrated to America with her family in 1890.[11] According to family history, Sebastian did not first build a sod house on his property, as was common of many of the homesteaders on the Great Plains, but instead was able to rely on his familial network to build a house of more permanent materials.[12]

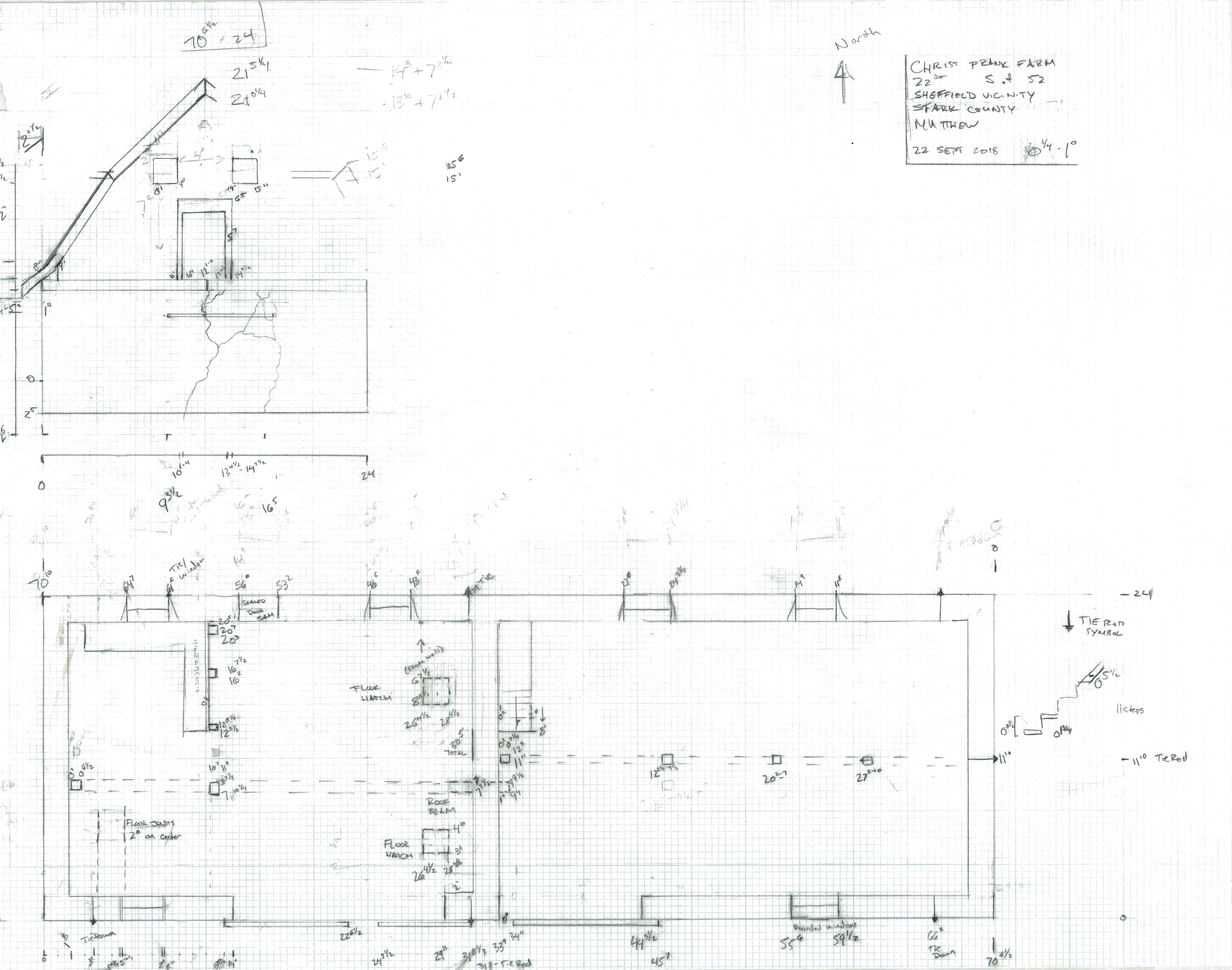

The first building on the farmstead appears to be a rock barn which measures over seventy feet wide and twenty-four feet deep with twenty-inch-thick, nine-foot-tall stone walls. The barn has a wood-framed gambrel roof. The ground floor plan reveals two distinct spaces divided by a stone partition wall. The western section of the barn measures approximately thirty feet by twenty feet, and the eastern section measures approximately thirty-five feet by twenty feet. The south elevation contains two sliding bay doors, one entering either section of the barn, and two small windows. The building contains a single interior staircase to the hayloft above, located in the northwest corner of the eastern section of the barn. Evidence in the hayloft floor suggests that only the eastern section of the barn was used to house livestock, as the hay-drops are only situated over that half of the barn. In the later part of the twentieth century, the western half of the barn was used as a workshop and for equipment storage.

The barn contains a couple of curious construction elements which call into question its use history. First, the eastern bay door is immediately adjacent to the stone wall, and the door jamb is fixed immediately to that wall. The hay loft floor is supported by summer beams which in turn are supported by six-by-six posts, but these summer beams appear to be a later addition. Not only are the summer beams in either room not aligned, but the space where they are saddled into the central stone partition wall appears to have been carved out of an existing wall. Further, the summer beams are supported by posts at the stone walls—an element that would not have been necessary if the beams were part of the original design conception as the stone walls would have offered sufficient support. The exterior of the stone walls has been stuccoed over, but the north elevation contains a crack in the stucco that runs vertically through the height of the exterior wall at the approximate place of the interior partition wall. This evidence, as well as the eastern door’s jamb position suggest that the barn was built in two sections, the western half of the barn having been built first. This is complicated, however, by the continuous roof framing. If the barn was built in two sections, then the entire roof had been rebuilt, and if the roof had been rebuilt to incorporate a hayloft, then it would have been necessary to add summer beams to disperse the weight to the stone walls.

The second oldest building on the site appears to have been the house. It is a one-and-a-half story wood frame structure, three bays (thirty-six feet) wide and two bays (twenty-four feet) deep, with a side-gabled roof with a distinctive ‘kick’ at the eave. The original east elevation has been largely altered and is now mostly obscured by a large kitchen addition built in 1971, but it appears that this face of the house may have had two doors and at least three windows.[13] The north and south elevations both contain two windows in the ground floor and paired windows in their gable walls. The west elevation contains only a gabled dormer in the roof and one opening in the first story which was converted into a picture window during the second half of the twentieth century.

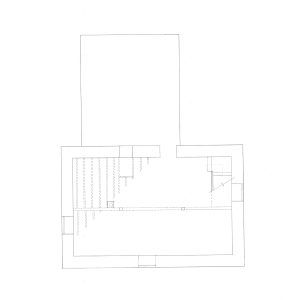

The interior plan of the house is atypical of the house plans that we’ve so far seen in Stark County, and understanding of the historic uses of the spaces is complicated by layers of alterations. The house has a fieldstone foundation with a full cellar beneath its historic core. A milled six-by-six summer beam supported by six-by-six posts spans the entire length of the house. Today, the cellar is accessed from a staircase in the 1971 kitchen addition, but historically was accessed by a box stair in the house’s southeast corner. Elements of this stairway still exist. The joists also show evidence of a coat chute in the east wall, although there is no other evidence of a coal bin.

The main floor of the house has a very irregular room layout. From the kitchen addition, you enter into a small room which currently functions as a sort of vestibule before entering the living spaces of the house. Past this small room is the main living area of the house, which now functions as a living room. This room has the finest finishes of the house, including a pressed tin ceiling and door frames styled with the most intricate cornices and carved plinth blocks. This room appears to have historically been the only first-floor room with access to the chimney stack. There are two small (ten by ten foot) chambers at the north end of the house. The south end also contains two rooms, one of which is approximately nine-foot square and has been opened into the living room space. The other of these two spaces is currently partitioned to serve as a laundry room, a bathroom, and a staircase to the upper floor. It’s unclear how this room historically functioned or how it was laid out. Historically this space would have been the access point to both the staircase up to the second floor and the staircase down to the cellar, but these staircases were not stacked on top of each other. There also appears to have been an exterior door at and either one or two windows at the eastern wall. Also curious about the floor plan are the two angled walls. One of them was clearly installed to allow a door into the northern bedroom, but was this original? Or was this door moved? The purpose of the second angled wall is more obscure. Was this added in a remodel? Where was the cookstove located before the kitchen addition? Was there a second chimney?

The second floor of the house is laid out as we’ve seen in other houses in Stark County, with two rooms both utilized as bedrooms.

According to family history, “While the pioneers built their first homes of sod, Mr. Sebastian Frank, as his father, built a more substantial and permanent home of sandstone which not only served him well for 45 years, with an addition in 1912 and more modern equipment, but this home is still in use today [1980].”[14] This statement is curious considering that the house at the Sebastian Frank Farmstead is built of frame, and may suggest that the original house was remodeled and expanded for use as a barn. The 1912 date may reference the year that the frame house was built. The Michael and Marianna Frank Farmstead, Sebastian’s father’s farm, is no longer extant, but Sebastian’s brother’s farm, the Raymond and Margaretha Frank Farmstead, homesteaded in 1906 is located two miles to the west.[15] His sister’s farmstead, the Clemens and Barbara Steier farmstead is located on the section between.[16] These two farms offer additional insight into the original design of Sebastian Frank’s farm. The original section of the barn at Sebastian Frank’s farm is approximately the same dimensions as Raymond’s stone farmhouse. The original barn at Raymond’s farm (no longer extant) was built with a thatched roof.[17] If Sebastian’s stone house may also have had a thatched roof, and when the house was expanded as the barn and the wood superstructure was added, summer beams would have been necessary to support the additional weight. Sebastian Frank’s new farmhouse shares commonalities with Clemens Steier’s farmhouse, including diagonal walls and interior finish details, and both houses demonstrate cultural evolutions and assimilation into American culture.

Sebastian and Anna had twelve children, and a larger farmhouse would have been desired to raise a large family.[18] They lived on the farmstead for over 45 years until November 1950 when Sebastian and Anna retired to Dickinson, passing the family farm to their youngest son Christ.[19] Christ married Monica Schwindt in 1951 and the couple had one son before Monica’s passing in 1953; the following year, Christ married Lorraine Billman, and the couple had six more children. Christ and Lorraine Frank lived on the family farm until 2001 when they retired to Dickinson.[20] Christ passed away in 2014, and the farm was sold to a descendant of Clemens Steier.

The Jacob and Helena Wandler Farm

TRAVIS OLSON

(Also known as the Joseph and Regina Binstock Farm.) Like the Sebastian and Anna Frank farmhouse, the Jacob and Helena Wandler farmhouse has a double-pile, or two-room-deep plan. The Wandler house, however, represents a more ethnically German-Russian building tradition, not only in its plan, but also in its materials and building technology.

Jacob Wandler married Helena Froelich at St. Francis Xavier in Rastadt, Russia in the Beresan District of what is now the Ukraine. In 1898, at the age of 33, Jacob sailed with Helena and their four children from Bremen to America, through New York’s Ellis Island.[21] By the time the federal census was taken in 1900, Jacob, Helena, and five children (nine-month-old Margaret was born in North Dakota) were living on a claimed 160-acre homestead near Schefield.[22] The farm was officially patented in 1906.[23] In addition to the farmhouse, the only building which is known to have been built for the Wandler family is a stone barn, located just northeast of the house. Helena Wandler died in 1936, and Jacob Wandler died in 1938; both are buried in the St. Pius Cemetery in Schefield.

After the Wandlers’ deaths, the property was sold to Joseph J. Binstock, who had patented the farm immediately to the north in 1910 and 1911.[24] It appears that Joseph J. and Regina Roller Binstock continued to live on their homestead, renting the Wandler farmhouse to one of their children, but further research is necessary to determine how the property transferred to its current owner, Gerald Binstock.

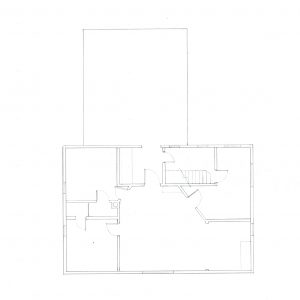

The Wandler-Binstock Farmhouse is more similar to the double-pile house plan that previous scholars have identified in German-Russian regions in the Northern Great Plains than the Sebastian and Anna Frank house plan, but is still a notable departure. William Sherman suggested that the typical two-room-deep house plan consisted of six rooms (three rooms wide and two rooms deep) with each of the rooms aligned with one another.[25] In Sherman’s model, one enters into what he calls the vordere kuche (or front kitchen), in cases where the vorhausl has been subsumed into the main block of the house, these two spaces are synonymous, but just as frequently the house still contains the separate front vestibule. The room off the back of the front kitchen is the main kitchen. The room on the right hand side he calls the staatsstube (directly translated to ‘state room’ but utilized much as the English parlor).[26] The room off the back of the staatstube functioned as the parents’ bedroom, while the two rooms at the left end of the house were the family’s bedrooms.

The Wandler-Binstock House, however, historically contained seven rooms, with three rooms in the front and four rooms in the back. Where it is most common for these double-pile plans to have a central kitchen, this house is different in that the kitchen is located in the northeast corner, and the presence of the in-floor door to the cellar and the location of the pantry in the northwest corner suggests that the kitchen’s location has not been moved. The central room of the house was used as the family’s main public-facing living space. Two doors opened off of the back of the living room into two smaller bedrooms. During the Binstocks’ ownership of the house, the northern of the two rooms functioned as the parents’ bedroom and the slept the four brothers. A second storage room occupied the southwest corner of the house, accessed through a door in the south wall of the boys’ bedroom. The large room off the southern wall of the living room was probably conceived as the parents’ bedroom, but the Binstocks used it to sleep the family’s five daughters.[27]

Historically the house had four openings across the front of the house, including two doors: one which entered into the main living space of the house and a second that entered directly into the kitchen. Like many of the other farmhouses we’ve seen in Stark County, the wind-facing north and west sides of the house contained fewer openings than those on the south and east sides, but the two-room-deep plan required windows on the east side to bring natural light and ventilation into the rear rooms of the house.

The location of the kitchen at the end of the house rather than the middle marks a conceptual departure from other farmsteads that we’ve seen in the region. In most cases, all of the sleeping rooms of the house are accessed from the kitchen, or the kitchen functions as the home’s center of activity. At the Wandler-Binstock house, this position has been replaced by the parlor, or what Sherman may have referred to as the staatstube. This means that there is a progression of the privacy of the rooms; visitors could enter the kitchen but would need to be invited into the more private family space, and the sleeping chambers were not accessible from the kitchen.

The Wandler-Binstock House was demolished in the fall of 2018.

The Stephan and Louisa Boehm Farm

TRAVIS OLSON

This year also offered us a foray into the architecture of another ethnic group, the German-Hungarians. In the interviews that we conducted in 2017, many people of German-Russian descent mentioned the German-Hungarians as being similar yet different, and during our return trip we found ourselves with the opportunity to see a German-Hungarian farmstead northeast of New England in Hettinger County.

Stephan S. Boehm and Louisa Betchner were married in Jozseffalva (German: Josefsdorf), in the Banat Region of Hungary on July 5, 1903.[28] In February of the following year, Louisa gave birth to their first child Katharina.[29] With the interest in beginning a new life for his family, Stephan and his brother Johann left Hungary for America from the Port of Bremen, sailing aboard the S.S. Hannover and arriving in the Port of Baltimore in April 1904.[30] The brothers gave the name of Johann “Lamping” (likely an Americanized version of the name Lampl) in Philadelphia as their point of contact. Louisa and her infant daughter left Hungary four months later, sailing aboard the S.S. Rhynland from Antwerp; they arrived at the Port of Philadelphia 17 August 1904.[31]

Little is known about the family’s early years in America. The 1910 Census listed Stephan and Louisa Boehm living with two children, Eva and Steven (their daughter Katherina had died in August of 1905), at 1527 N Hancock Street in Philadelphia’s Kensington Neighborhood where Stephan was employed as a hatter in a hat factory. Stephan’s brother (employed as a spooler at a silk mill) and his wife Catherine also lived in the small rowhouse, as did German-Hungarian boarders Nicholas Bruner and his wife Margaret, and Stephan’s brother-in-law Nicholas Betchner.[32]

Family history remembers that Stephan and Louisa Boehm came to North Dakota in 1910.[33] Stephan established a homestead in McKenzie County (SW ¼ S34, T147N R99W) which he received patent for on July 22, 1914.[34] About five years later he traded the homestead land for land in Section 20 of Clark Township (S20, T136 R96) in Hettinger County.[35] Stephan and Louisa had five children live to adulthood: Eva, Stephan, Rose, John, Adam, and Nick, and they raised Eva’s son George as their own.[36]

Stephan and Louisa Boehm chose to build their Hettinger County farmstead between two low hills to partially protect the house from the cold winds from the north and west. Built near the top and into the side of one of the two of those hills, the one-and-a-half story house is effectively perched over the rest of the farmstead. The dwelling would have shone in the mid-day sun for the weeks following its annual whitewash coating. The house was constructed of twenty-two-inch-thick stone walls with wood-framed interior walls, and the house contains a full cellar. The southern-facing front elevation of the house contained a projecting vestibule, or vorhausl, at its center, designed to keep the wind from blowing in dust and snow, common in German-Hungarian and German-Russian housing.[37] The plan, too, reveals Germanic influences. The front door enters directly into the main workspace of the house, the kitchen. A door to the left enters the formal room of the house, the parlor-bedroom. The eastern end of the house is divided into two smaller rooms, a front room that may have been used as a bedroom or for storage, and a back room which functioned as a pantry and an enclosed stair-hall with access both to the two bedrooms above and the cellar below. The house has a full brick chimney that runs through the entire height of the house at both the partition wall between the kitchen and parlor and the wall between the two bedrooms upstairs. Standing adjacent to the house to the east, approximately ten feet from the main house, is a one-room wood-frame bunk house.

We visited the farmstead with a cousin of the Boehm family who explained his memory of the ways that the interior spaces were used. The kitchen space was primarily thought of as women’s space, and when the house hosted family gatherings the women tended to gather in the kitchen while the men gathered in the parlor. The two bedrooms upstairs were used by the children, with the girls using the more private room to the west while the boys slept in the room at the top of the stairs. In warm weather, when the bunk house was not used to sleep hired farm labor (particularly during autumn harvest), some of the boys slept out of the main house.[38]

The farmstead contained seven other farm buildings, two of which are in ruin. Just north of the house stands a stone-walled icehouse, also built into the side of the hill with an ice shaft dug straight down into the rock. East of the house stands a wood-framed workshop and a machine-shed with a clipped-gable roof. The farm also contains two barns, one with stone and one with framed walls, and both with gabled roofs. An aermotor windmill stands downhill south of the house, and a metal grain bin stands on the eastern end of the farmstead.

The Stephan and Louisa Boehm Farmstead is of particular interest to us not only because it is first that we have investigated in the area built by a German-Hungarian family but because it is amongst the finest collections of period buildings that we have yet seen. The plan of the house is also the first we have encountered which shows an evolution of the traditional Germanic three-room plan (also known by architectural historians as the Continental Plan) modified and elongated in the Eurasian Steppe and then transplanted to the Northern Great Plains. This is also the first farmstead which retained a bunk house, a building type that we have since encountered more and more frequently. It begs the question, how common were these? How often and in what ways were they used? Further, the Boehms lived for more than five years in one of the most densely populated neighborhoods of Philadelphia in the 1900s, a drastic contrast to the sparsely populated plains of Western North Dakota. How did that experience shape the way they constructed their homestead?

127 First Street SW, Dickinson

TRAVIS OLSON

The 2018 field school also introduced us to our first urban example of what we assume is German-Russian construction. More research is needed to know who built the house located at 127 First Street SW, as well as the history of its ownership, but it does exhibit some telling signs of what points to German-Russian craftsmanship. Foremost of these signatures is the house plan, which reveals a four-room arrangement similar to the Stephan and Louisa Boehm Farmhouse.[39] The house contains a vorhausl which enters directly into the centrally-located kitchen. The room to the left upon entering the home, located at the front of the house, is the largest and finest of the rooms. The two rooms to the right, are smaller. The front room may have historically been used as a bedroom, while the back room, which now functions as a bathroom, may have either originally been a storeroom and pantry or it may have functioned as another small bedroom.

The house’s building materials are also somewhat of a mystery. A hole in the plaster revealed that the house is built of mud, but because the walls have been encased with plaster and siding, its not clear if the house was constructed of stacked mud bricks or if it the walls are rammed earth—a German-Russian tradition commonly exhibited in houses built by German immigrants in the Russian Steppe. Of German-Russian construction in urban settings, the historian Jesse Tanner writes,

“These people are generally very poor when they come to this country. The rich do not need to emigrate. They build mud houses as they did in southern Russia, because they are not able to have better ones. In building these houses they usually make the mud, which is mixed with straw, into bricks which are allowed to dry in the sun. Those who are near the railroads often build their houses of old ties, setting the ties upright in the ground to form a wall and filling the crack between them with mud. …A few years ago there were so many of these houses, both built of mud and those built of tics, in some of the villages of our state, that they gave the village a decidedly foreign aspect. This was true of Richardton between 1895-1900, and it is still true of the part of Dickinson south of the railroad.”[40]

According to Johnson, Hufstetler, and Emerson, the 1927 Sanborn Insurance Maps may show as many as 100 houses with ethnic architectural characteristics, but perhaps as few as five remain with architectural integrity.[41]

It is our hope to continue research in South Dickinson and Richardton, with the goal to identify other houses built by German-Russian immigrants to better understand the urban house typology.

- A few sod buildings survive near our project area, including a former post office in Grassy Butte (https://www.loc.gov/item/2017781030/). ↵

- William C. Sherman, "Prairie Architecture of the Russian-German Settlers," in Richard Sallet, Russian-German Settlements in the United States. (Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1974), 185-195. and Alvar W. Carlson, “German-Russian Houses in Western North Dakota.” Pioneer America13, no. 2 (September 1981): 49-60. ↵

- Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957. Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service; National Archives at Washington, D.C. Microform Serial: T715, 1897-1957, Roll 0023, Page Number 90. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- United States Census Bureau, Twelfth Population Census of the United States, 1900. Dickinson Village, Stark County, North Dakota, 128A. ↵

- Jakob Hecker (Stark County, North Dakota) Homestead Patent No. 12793, “Land Patent Search,” digital images, General Land Office Records (http://www.glorecords.blm.gov/PatentSearch: accessed September 2019). and Nick Hecker (Stark County, North Dakota) Homestead Patent No. 213790, “Land Patent Search,” digital images, General Land Office Records (http://www.glorecords.blm.gov/PatentSearch: accessed September 2019). ↵

- United States Census Bureau, Fourteenth Population Census of the United States, 1920. Oakland City, Oakland Township, California, 2B. ↵

- United States Census Bureau, Fourteenth Population Census of the United States, 1920. Juarez Precinct, California, 20A. and United States Census Bureau, Fourteenth Population Census of the United States, 1920. Berkeley City, Oakland Township, California, 5B. ↵

- United States Census Bureau, Fifteenth Population Census of the United States, 1930. Township 137 Range 96, Stark County, North Dakota, 1A. and United States Census Bureau, Sixteenth Population Census of the United States, 1940. Stark County, North Dakota, 3B. ↵

- Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36. National Archives at Washington, D.C. Microfilm Serial: M237, Roll 0040, Page Number 103. ↵

- United States Census Bureau, Fourteenth Population Census of the United States, 1920. Township 137-96, Stark County, North Dakota, 5A. ↵

- George P. Aberle, Pioneers and their Sons: One Hundred and Sixty-Five Family Histories. (Bismarck: Bismarck Tribune Company, 1980), 382. ↵

- Betty Gardner and Eleanor Olson, eds. New England Centennial 1886-1986: Century of Change. (Bismarck: Richtman’s Printing, 1986), 261. ↵

- Aberle, Pioneers and their Sons, 382. ↵

- Alex Leme, “Raymond Frank Farm,” in Folk Farmsteads on the Frontier: North Dakota Field School 2017. Anna Andrzejewski, ed. eBook. Available: https://wisc.pb.unizin.org/ndfieldschool2017/ ↵

- Michelle Prestholt, “Clemens Steier Farm," in Folk Farmsteads on the Frontier: North Dakota Field School 2017. Anna Andrzejewski, ed. eBook. Available: https://wisc.pb.unizin.org/ndfieldschool2017/ ↵

- Jacob Frank, Interview by Lon Johnson and Mike Koop, 9 August 1991, in Lon Johnson, et al., “Ethnic Architecture in Stark County, North Dakota: A Historic Context,” State Historical Society of North Dakota Division of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, [Bismarck, North Dakota, 1992], 62. ↵

- United States Census Bureau, Fifteenth Population Census of the United States, 1930. Township 137 Range 96, Stark County, North Dakota, 2A. ↵

- Gardner and Olson, 264. ↵

- Obituary: Christ S. Frank. The Bismarck Tribune, Bismarck, North Dakota. 30 July 2014. ↵

- Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957. Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service; National Archives at Washington, D.C. Microform Serial: T715, 1897-1957, Roll 0021, Page Number 99. ↵

- United States Census Bureau, Twelfth Population Census of the United States, 1900. Township 137 Range 96 and Township 137 Range 97, Stark County, North Dakota, 29. ↵

- Jakob Wandler (Stark County, North Dakota) Homestead Application No. 28384, “Land Patent Search,” digital images, General Land Office Records (http://www.glorecords.blm.gov/PatentSearch: accessed September 2019). ↵

- Josef Binstock (Stark County, North Dakota) Homestead Patent Nos. 121070 and 227963, “Land Patent Search,” digital images, General Land Office Records (http://www.glorecords.blm.gov/PatentSearch: accessed September 2019). ↵

- William C. Sherman, “Prairie Architecture of the Russian-German Settlers,” in Richard Sallet, Russian-German Settlements in the United States. (Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1974), 185-195. ↵

- Sherman suggests that its most common for the formal room to be on the right side upon entry, but in nearly every example we have seen in Stark and Hettinger Counties, the most formal room is to the left. ↵

- Gerald Binstock, Interview by Travis Olson, 12 August 2019. ↵

- In the historical record Stephan’s name is alternately spelled Stefan, Stephan, and Stephen. His son’s name appears as either Stephen or Steven, but he was locally known as Steve. The Germanic spelling of the last name was Böhm, but American records spell it Bohm, Behm, and Boehm. The Germanic name Betschner was Americanized to Betchner. ↵

- Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004. Record Group Number 85, Series T840. List 046. ↵

- US Customs Service, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service. Baltimore, Passenger Lists, 1820-1964. Record Group 85. List 30. ↵

- Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004. Record Group Number 85, Series T840. List 046. ↵

- United States Census Bureau, Thirteenth Population Census of the United States, 1910. Philadelphia City, Pennsylvania, 13B. ↵

- Peter Betchner, Interview by Travis Olson, 22 September 2018. ↵

- Stefan Boehm (Stark County, North Dakota) Homestead Patent No. 423125, “Land Patent Search,” digital images, General Land Office Records (http://www.glorecords.blm.gov/PatentSearch: accessed September 2019). ↵

- United States Census Bureau, Fourteenth Population Census of the United States, 1920. Clark Township, Stark County, North Dakota, 15A. ↵

- Peter Betchner, Interview by Travis Olson, 22 September 2018. ↵

- Sherman, 187. ↵

- Peter Betchner, Interview by Travis Olson, 22 September 2018. ↵

- The Boehm farmstead was built by a German-Hungarian family, but because Dickinson has historically had a much larger German-Russian population than German-Hungarian, the house at 127 First Street SW was more likely built by a German-Russian immigrant than a German-Hungarian. More research is needed to verify the nationality of the builder. ↵

- Jesse A. Tanner, “Foreign Immigration into North Dakota,” Collections of the State Historical Society of North Dakota 1. (Bismarck, ND: Tribune, State Printers and Binders, 1906), 200. ↵

- Lon Johnson, et al., “Ethnic Architecture in Stark County, North Dakota: A Historic Context,” State Historical Society of North Dakota Division of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, (Bismarck, North Dakota, 1992), 71.{/footnote] German-Russian houses are identifiable on the Sanborn Maps by their long, linear proportions and the presence of a vorhausl. These houses are often oriented with their narrow, gable end facing the street, orienting the house sideways on their lot. This, according to historian Karl Stumpp, aligns with the orientation of village houses in the Black Sea Region.[footnote]Karl Stumpp, The German-Russians: Two Centuries of Pioneering. (New York: Edition Atlantic-Forum, 1978), 21. ↵