A Field and Its Forms

Publications and Provocations

The 21st-Century Publishing Landscape

In order to understand the questions we should be asking about our primary and secondary sources, we must first understand the relationships among current-day academic publishing institutions. In this section, I highlight the ways in which the forms, reading platforms, and distribution structures associated with scholarly publishing increasingly reflect the efforts of a few influential corporations to restrict the reuse of texts, to commodify user data, and to maintain negotiating power over public institutions. I argue that this matters for Victorian studies because such business models actively redefine our relationship to the nineteenth-century archive and work against many scholars’ central motivations for writing and teaching. By devoting more attention to these concerns, we have the opportunity both to improve our own discipline and to make an impact on other fields by illustrating how writing and power operate in concert.

Broader Contexts

Scholars in literary studies are becoming increasingly aware of the ways in which social and structural inequalities stratify the academy along lines of privilege. These compounding factors affect every institution of higher learning and research, although their manifestations differ depending on the institution’s relationship to its community and to broader legal systems.

Writ large, it can be easy to for us recognize the systems that influence how citizens with the most and the least power in society interact with educational and scholarly media. Some government policies reduce access to texts in ways that disproportionately affect low-income people. To name one example, China’s “Great Firewall” filters access to information sources and alters the kinds of texts that people feel comfortable publishing (Zhi-Jin Zhong et al). Because educational opportunities are often linked to privilege, such statewide policies combine with social and economic factors to direct the academic conversations students gain exposure to. As an illustration of this dynamic, one study observed that Chinese college students who were proficient in English and had studied abroad were more likely to use Google to access academic articles published outside of China (Fu and Karan 2750-51). This is significant because many of the search engines supported by the state provide only partial access to work published outside of the country. China also limits access to Wikipedia, thus preventing citizens from either learning from or contributing to a knowledge commons that many students use as a first step in research (OONI).

By contrast, there are other public policies that expand access to academic research. In the United Kingdom, the Higher Education Funding Council and Research Councils UK, (HEFC and RCUK), have not only required that results from projects that receive public funds be circulated in open-access publications, but they have also included open-access publishing as a prerequisite for inclusion in the 2021 Research Excellence Framework (MIT Open Access Task Force 6-7). Open Access (OA) policies aim to level the playing field for internet users to explore academic publications. They also reframe open-access publishing as worthy of respect, an important shift when we consider how much the prestige of a journal can affect its desirability for scholars and tenure committees. As a result, more readers in the United Kingdom and many other countries are able to read authors’ works.

Overarching currents like these establish the basic parameters for our discussions about contemporary authorship and often determine their focus, but conversations about policy at a governmental scope don’t capture the whole picture. What is less obvious are the institution-specific policies that intersect with one another to shape media access within these broader legal systems. We ignore these dynamics at our cost: policies at the level of industry, university, or college affect how we are able to write, speak, and teach. Scholars, students, and the public have the opportunity to participate in these institutions in ways that shift our trajectory toward a more accessible knowledge commons. First, however, we need to address a lack of awareness about how scholarly and educational texts are situated in the present day.

Members of the scholarly community are already working to change this by investigating how the publishing industry’s economic and legal relationship to universities, individual authors, and peer reviewers can affect academic freedom. It’s worth noting, however, that the primary drivers of these conversations tend to be authors in the sciences and social sciences rather than the humanities. There are many reasons for this. In a field such as medicine where the purpose of publishing is, at least on its surface, to limit the amount of human suffering in the world, forces that reduce the spread of knowledge take on a sinister dimension. Moreover, the direct influence of publishing norms on researchers’ output is often more obvious in the sciences and social sciences because scholars in these fields tend to rely more on grant funding to do their work. The ability to publish in high-impact journals often correlates with increased funding for future research, meaning that the publishers, editors, and peer reviewers affiliated with high-impact journals play a particularly visible role in shaping a field’s research directions. When the profit motivations of these intermediary figures seem at odds with the motivations of the scientific community, scholars see the benefit in digging deeper.

In contrast, no one’s bodily health depends on our ability to access the latest volume of Victorian Studies or PMLA. This dynamic has a plus side in that it makes it more difficult for publishers or aggregators to set a high price for humanities publications. However, it also makes it less likely for us to view a lack of access to our scholarship as an urgent problem. Yet for humanities scholars to leave the main part of access advocacy to other disciplines is a mistake. Those who study the long nineteenth century are well-positioned to recognize how the broader and more-localized legal policies associated with our writing intersect. Our work and our teaching depend on our interactions with scholarly publications as well as with archives of physical texts and public domain materials. We are also methodologically well-prepared to imagine ways to disrupt the practices that restrict our research and teaching.

Monopolizing; Monopolicing

What, then, does the most influential portion of the English-language scholarly ecosystem look like? Information scholar Joe Karaganis can set the stage for us with his description of how publishing industries have evolved over the past thirty years (6). Thanks in large part to the ability to share information through digital networks, he observes,

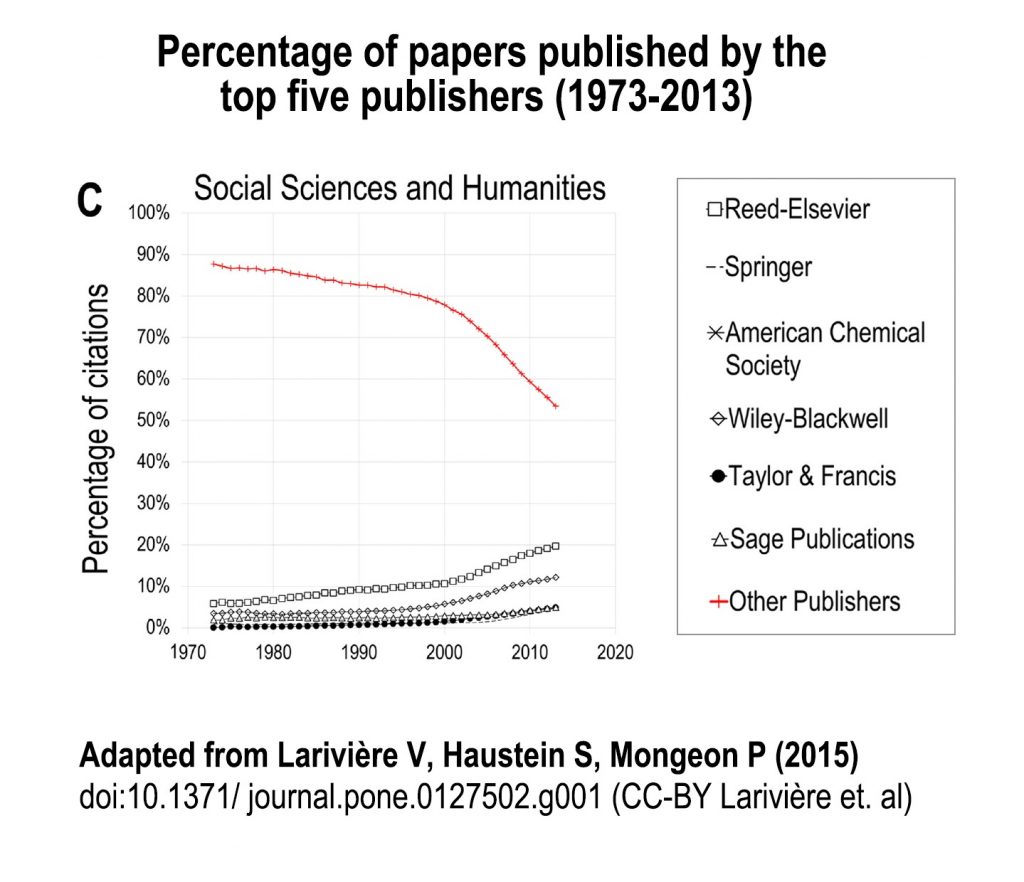

by 2013, five companies—Elsevier, Springer, Wiley-Blackwell, Taylor and Francis, and Sage—published 50 percent of all research papers, rising as high as 70 percent in the social sciences (Larivière, Haustein, and Mongeon 2015). In textbooks, similar processes of consolidation left three publishers—Pearson, McGraw-Hill, and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt—in command of over half the Anglophone market by 2014, and in positions, together with a handful of technology companies, to dominate the emerging fields of digital delivery and learning platforms. (Karaganis 6)

In her examination of the economics of scholarly production and open access, Heather Morrison connects dollar amounts to these monopolies, highlighting the gulf between publisher profits and the rewards offered to the scholars involved in article creation and peer review. As of 2013, she notes, scholarly publishers collected US$8 billion in revenue, which amounts to profit margins “typically in the 30–40 percent range” for the largest players (Morrison).[1] Even though there are real costs associated with coordinating, marketing, hosting, and printing an academic journal, Morrison stresses, publishers do not actually bear much of this burden. She argues that publishers can make such high profits because of “the large percentage of the work that is done on a voluntary basis by scholars paid through university salaries, and in-kind support that is generally available at universities, such as computers, software, and connectivity” (Morrison).

There is a silver lining for humanists in these numbers. In academic journal contexts, at least, the five multinational publishers that dominate the sciences have found it comparatively difficult to obtain a foothold over more than twenty percent of the market for the humanities and arts (Larivière et al. 2). However, this does not lessen the need to ask critical questions about who we include or exclude when we publish scholarship in our field. For-profit institutions control much of our archive at points upstream by shaping how we interact with scholarly databases.

Publishing Changes in the Social Sciences and Humanities (1973-2013)

Toggle the slide below to alternate between graphs describing changes for papers, journals, and citations.

‘Big Five’ publishers have a low market share in the social sciences and humanities compared to the STEM fields, but their influence has been rising in the years since digital publishing and the internet have arrived on the scene (Larivière et al., Bergstrom et al. 9425).

Publishing Changes in the Social Sciences and Humanities (1973-2013)

‘Big Five’ publishers have a low market share in the social sciences and humanities compared to the STEM fields, but their influence has been rising in the years since digital publishing and the internet have arrived on the scene (Larivière et al., Bergstrom et al. 9425).

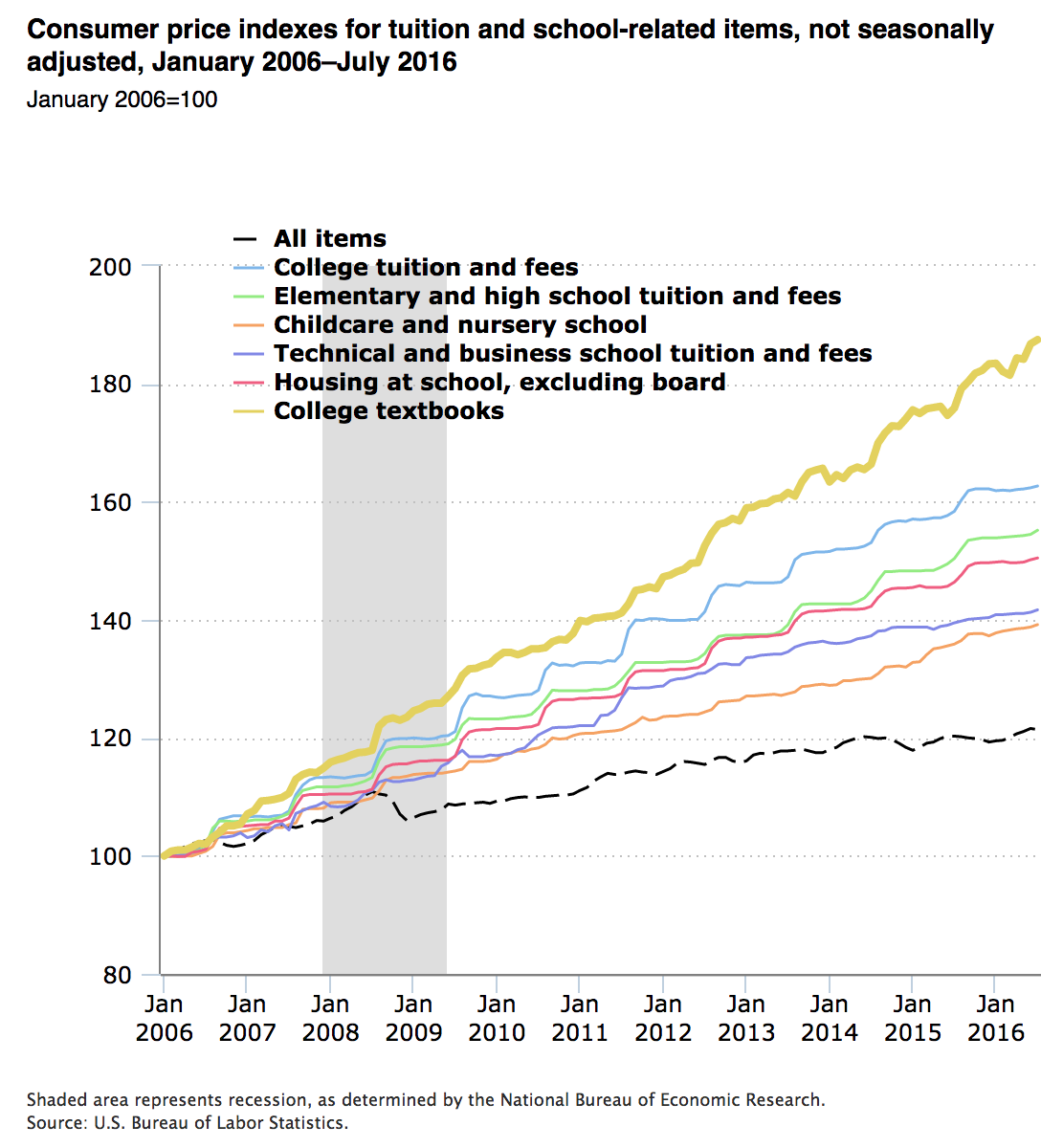

As publishers’ profits from scholarly publications increase, a similar consolidation of power is occurring for educational texts. Profit margins for textbooks far exceed the profit margins that exist in most other businesses. As we will explore shortly, corporations use similar strategies to achieve these profit margins in research and educational publishing. For content distributors, there is a significant incentive to maintain control over the publishing landscape, as this is a profitable industry. According to the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, the consumer price index for college textbooks increased by 88% between 2006 and 2016. By way of contrast, when we omit college textbook prices, the average price index increase for college tuition and fees, elementary and high school tuition and fees, childcare and nursery school, technical and business school tuition and fees, and housing at school (excluding board) combined was 50%. During this 10-year period, the price index increase for all items the CPI measures was 21%[2]

United States Consumer Price Index Increases for Textbooks 2006-2016)

A major site of publishers’ growth is in digital sales, an impact that is so significant that educational publishers are beginning to identify more with ebook, database, and courseware production than print publication. To some degree, digital objects are desirable because they often have lower production costs: industries simply pay for software development and server storage rather than for the cost of printing and physical distribution. Yet for the most part, digital publishing is an asset because it allows companies to exert continued power over a piece of media even after readers have purchased it. As industry giant Cengage itself boasts in its March 2018 report to shareholders, “In contrast to print publications, our digital products cannot be resold or transferred. We therefore realize revenue from every end user” (“Annual Report” 6). In keeping with larger trends in the industry, Cengage explains, “Our sales, marketing & services teams have shifted over the last few years from a textbook to a software sales & support model” (“Annual Report” 6, as cited in Wagstaff).

Forms and Platforms After the Digital Turn

The digital technologies that continue to reduce publishers’ overheads for production and circulation are a source of anxiety for those same publishers. Just as occurred during the nineteenth century, forms of mechanical reproduction in the present day are rapidly increasing audiences’ ability to access and redistribute texts on their own account. And, as is often the case, anxiety and influence combine to inspire innovative new forms of policing content. Publishers have felt the need to change their own distribution channels as well as the forms of texts that users can access, thereby reducing users’ ability to alter or share media. This has implications for our reading and writing practices and for the public institutions that sustain them.

Digital Rights Management In Practice

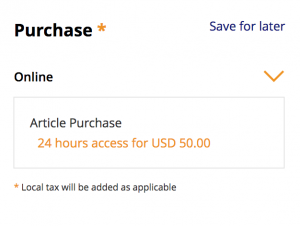

One way that publishers have sought to maintain control over texts is by shifting away from an ownership model to a mediated access model for articles and textbooks (Kenneally 1180-81, 1188). Rather than selling an object to purchasers, many companies offer the temporary ability to download a piece of media or view it within a rights-restricted reading platform.

A key advantage of this approach is that it allows companies to redefine our legal relationship to content. When companies sell licenses to access texts rather than transferring ownership of those texts, they can compel users to agree to ‘terms of service’ contracts as a precondition for viewing the media. Indeed, legal scholar Michael Kenneally notes, among other things, licensing agreements often require readers to relinquish even their right to fair use of that media (Kenneally 1206). This means that users are no longer permitted to do things such as reproduce images or text in educational resources or to create derivative works for the purpose of critique.

Kenneally points out the absurdity of such a requirement, observing that it is very difficult for people to accurately estimate their likelihood of using media before they access that media in the first place (1206). By the time a user can recognize how they might criticize an artifact or draw from it in their own work, it is often too late for them to do so without great difficulty. Rather than simply deciding how to best approach their critique or reuse, they must “weigh the hassle of renegotiating with the commandeering rights-holder (or the risk of proceeding with the fair use despite the contractual prohibition) against the difficulty of internalizing the benefits that the fair use would create” (1206). Kenneally concludes that when companies impose licensing agreements of this type, they can “chill value-creating fair uses in a way that affects society and not just the parties to the argument” (1206). Ultimately, licensing arrangements allow publishers to exert more authority over readers’ practices, create an incentive for readers or libraries to continue subscribing to the publisher’s services, and allow publishers to monitor data about user interactions.

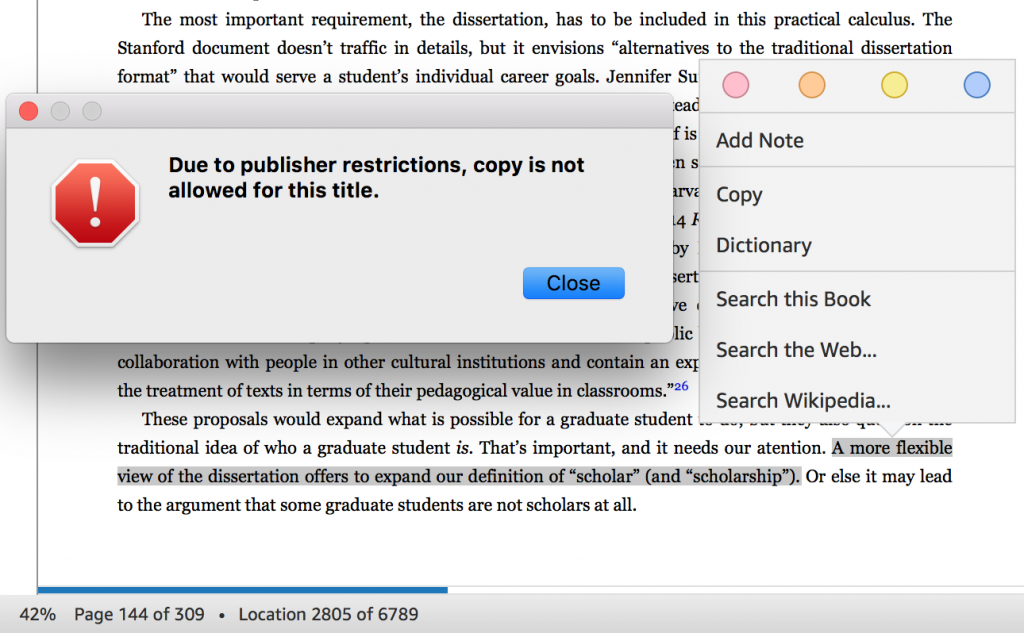

Licensing agreements not only affect the way we integrate content into our articles or YouTube videos, but they also affect our everyday reading practices before we ever pick up our pens to write. This is particularly noteworthy at a time when technological developments are allowing scholars to interact with texts in new and productive ways. For one thing, the reading platforms and file formats that publishers offer are often deliberately limited by Digital Rights Management (DRM) technologies. Yet as we’re reminded by the Rebus Foundation, a nonprofit organization that supports open educational resource creators, “the issue when it comes to scholarly reading is that it is a much more dynamic, active, and interactive process that is simply not supported by existing platforms (“Considering Librarians”). The librarians that Rebus interviewed suggest that the large size and profit motivations of the corporations that sell aggregator services actively reduce the level of creativity afforded to readers. When vendors design proprietary platforms for licensed content, “because that vendor is having to work with so many different publishers with so many different levels of risk that they’re willing to take, they end up going with the lowest common denominator” (“Considering Librarians”).

Limited reading platforms are especially frustrating at a time when new trends in application development are expanding how writers can speak to one another in the margins, extra-illustrate their notes, or reorganize and juxtapose quotations in a dynamic network. These developments often arise from many different collaborators building on one another’s tools for the sake of improving them for everyone. But our largest academic content providers have an incentive to bind readers to the kinds of “closed-silo systems” that are the least friendly to piracy and most pleasing to shareholders (“Considering Librarians”).[3] Such limitations are antithetical to creative forms of scholarly reading and to collaborative authorship.

Platforms in Action

Freewheeling and Big Dealing

In addition to artificially restricting the forms we use to read and write, academic content distributors use legal contracts to maintain and elevate their already-high profit margins. This disrupts the broader knowledge ecosystem and has disproportionately negative effects on the students, scholars, and institutions who are already at a financial or infrastructural disadvantage.

Steep journal prices are indirectly handed down to researchers, students, and the public through what are called “Big Deal” or “bundled” journal packages. In theory, these packages offer university libraries greater access to a wider range of journals, and this is technically true. However, in practice, ‘big deal’ contract markets are distorted, something that has a marked effect on literary scholars’ archives. Market distortions across different institutional contexts are particularly striking. Indeed, after making a series of FOIA requests and analyzing the resulting contract data, Bergstrom et al. argued: “There is ample evidence that large publishers practice price discrimination and that they have been able to set prices well above average costs” (9428). They add:

even with the institution-specific discounts resulting from bundled purchases, the prices per citation charged to large PhD-granting universities by major commercial publishers are much higher than those charged by major nonprofit publishers. Among the commercial publishers in our study, Elsevier’s prices per citation are nearly 3 times those charged by the nonprofits, whereas Emerald, Sage, and Taylor & Francis have prices per citation that are roughly 10 times those of the nonprofits. (9429)

Put a different way, if I received grant funding from the University of Wisconsin to do archival research, the journal contract that would allow UW–Madison affiliates to read the fruits of my state-funded labor might cost three times more if I published with Elsevier than if I published the same paper with a nonprofit academic publisher.

Statistics such as these are beginning to rankle academics, legislators, and the public,[4] and this is heralding some dramatic sea-changes in the scholarly ecosystem. More institutions are refusing to accept the agreements brokered by highly profit-driven publishers and aggregators. However, the largest publishers and aggregators are responding to these changes by shifting their approach to scholarly journal publishing, library licensing, and textbook distribution. Their strategies for doing so should concern scholars, instructors, and students alike: these corporations seek to redirect the conversation about open publishing in ways that maximize their own profits as well as expand their control over other aspects of the academic process.

To attach these claims to specific strategies, let’s consider a case study. In late February 2019, the University of California system rocked the world of scholarly communications by deciding that its libraries would not renew their contract with Elsevier for online journal access. This decision was partly motivated by the burden Elsevier placed on the system. The contract the university had signed with Elsevier in 2014 amounted to more than fifty million dollars spent on Elsevier’s services over the course of four years, and Elsevier’s prices continue to rise. In a 2019 UC-Berkeley news bulletin about the decision not to sign a new contract, Librarian Jeffrey MacKie-Mason informed the community that during renegotiations, the university had expressed an interest in reducing their Elsevier subscription fees, which were by this point “25 percent of UC system-wide journal costs” (Kell).[5]

Elsevier Subscription Fees – University of California (2014-2018)[6]

| Year | Total Cost |

| 2014 | $9,505,109.42 |

| 2015 | $9,742,737.43 |

| 2016 | $9,986,305.91 |

| 2017 | $10,260,928.63 |

| 2018 | $10,568,756.54 |

Source: Elsevier Subscription Agreement – Regents of the University of California, 9 April 2014.

While this was certainly a dispute over pricing, at its heart, it was a battle over how freely university faculty’s publications would circulate and how willing Elsevier would be to shift its business model to accommodate this. In Mackie-Mason’s telling, a key priority for the University of California was to ensure “default open access publication for UC authors: that is, that Elsevier would publish an author’s work open access unless the author didn’t want to” (Kell). Elsevier was willing to consider the open-access agreement for UC authors, but only if the university agreed to an 80% increase in payments, which amounted to “an additional $30 million over a three-year contract” (Kell). After an exchange of proposals and counter-proposals, the UC system let Elsevier know that they believed that the latest terms Elsevier had offered still did not address their own priorities for open-access publishing, and Elsevier pivoted to a new strategy. In MacKie-Mason’s words, despite knowing that the UC negotiators were dissatisfied,

[Elsevier] approached our faculty directly — faculty who are editors of Elsevier journals, who they have working relationships with — and also the media, and presented a rosy view of the offer they’d made to us. Their characterization of the offer left things out, and they didn’t mention what we’d proposed as conditions. They went public with it. So, we announced the end. (Kell)

Given the information available, it is difficult to pinpoint Elsevier’s exact motivations for this strategy. What is clear, however, is that Elsevier has a massive financial stake in directing the terms under which academics pivot to open forms of publication.

Their PR approaches reflect this. In public statements, major distributors such as Elsevier consistently try to paint a rosy picture of their investment in a knowledge commons, but there are strings attached. (Or rather, there are purse strings attached, and the beneficiary is typically the publisher rather than the public.) In her 2013 exploration of scholarly communication economics, Heather Morrison puts this in context by explaining the philosophy and strategy that Elsevier continues to pursue in the present day. When Elsevier describes its visions for “universal access” to content, she notes, it has a very specific business model in mind: “the basic idea is that if everyone who can afford to subscribe for pay–per–view to Elsevier’s resources does, and this is supplemented by a little bit of charitable access, then everyone has access” (Morrison). What should trouble us is that ‘open access’ models of this variety centralize power in the hands of the organizations which have the most to gain from ensuring that they are the only conduit for content. Morrison explains:

The major problem with this [model] is who owns the information. Elsevier is a corporation, an organization with a mission of maximizing profits to shareholders. As long as Elsevier continues a policy of full copyright transfer by authors [who publish in its journals], Elsevier is free to define the payment terms of its universal access. That is, everyone can have access — provided that they are willing to pay on Elsevier’s terms. Or, Elsevier could abandon this approach altogether in favor of another seen as more profitable. (Morrison)

Because maintaining content marketability depends on restricting access, publishers have every incentive to continue limiting fair use by placing restrictive licenses in between the public and scholarly materials. Despite its optimistic rhetoric, little about Elsevier’s mediated and highly-commercialized model addresses the underlying power differentials that perpetuate unequal access to research and educational resources. More than this, providing conditional access to content actually increases the power differential between public and for-profit institutions and gives publishers more marketing power to boot.

Morrison’s take on Elsevier’s motivations may be cynical, but Elsevier’s strategies during and after the University of California dispute do not lend themselves to a charitable interpretation. Of special note is the Open Access Strategy Manager job posting that appeared on Elsevier’s Careers website on or near March 2, 2019.[7] We learn that the three primary reasons for the position are to:

- “promote a positive policy environment through engaging closely with leading research organisations and helping the business develop and deliver impactful solutions and flexible policy frameworks”

- “support commercial goals by working closely with other teams to develop win/win Open Access (OA) solutions for the business and for the customer“

- “change the image of Elsevier, so that we are viewed as an organisation which supports OA” (Open Access Strategy Manager, emphasis mine).

Commentators were quick to notice how Elsevier’s description places emphasis on the “business” and the “customer;” the “commercial goals” of the publisher and the importance of “compliance,” “upward reporting,” “extracting data, and “deliverables.” Likewise—in this listing, at least—being “viewed as an organization which supports OA” appears to take priority over actually supporting OA. While “previous employment for a commerical [sic] organisation” is listed as a requirement, on paper, the job description places little value on past involvement with open access organizations.[8] The company’s response highlights the need for us to be on the lookout for moments when distributors present their goals as being the same as our goals. It also hints at the motivations we might fail to see if we do not put our formal and rhetorical analysis skills to work in these moments.

In raising these points about Elsevier’s commercial strategies, I am not arguing that it is wholly impossible for for-profits to advance educators’ and researchers’ goals. What I am saying, however, is that it is built into the soul and structure of commercial systems to work toward profit, and publishers’ and distributors’ goals don’t consistently align with the primary goals of humanities scholarship and education. In the present moment, many publishers’ financial motivations actively work against humanists’ motivations to create inclusive classroom spaces and scholarly dialogues. For these reasons, we need to be more intentional about where and under what conditions we invite for-profit institutions into our conversations and classrooms. We need to pay more attention to which rights and whose rights we are signing away when we engage with our research platforms. We also need to think more carefully about the ripple effects associated with changes in our scholarly ecosystem.

In the closing sections of this chapter, let’s consider some of these ripple effects in action, paying special attention to the changes that impact scholars of the long nineteenth century.

The Library, the Archive, and the Privatization of the Public Domain

As media piracy becomes more sophisticated and public sentiment shifts toward open access, major publishers are looking to diversify their market strategies. In addition to publishing monographs or providing access to articles, these institutions have begun to incorporate themselves into academic and educational workflows in new ways. They are embracing “vertical integration” strategies such as offering platforms, curated archives, and data analytics to appeal to customers (Posada and Chen 1, 8). One such vertical integration strategy is to direct traffic to company-held primary resources in addition to secondary ones. Scholars have taken note, and their warnings about “the privatization of the public domain” have taken on increased urgency in recent years.

The first thing we should recognize is that the privatization of the public domain is most feasible when financial pressures place archives and libraries in a bad position to bargain with the corporations who offer to digitize their collections. Evelyn Bottando’s investigation of Google’s library partnership program provides an apt illustration of how large organizations profit by directing the public’s access to the digitized media they collect. Bottando explains that even when user access is ‘free,’ Google profits from hosting artifacts like Youtube videos and public domain resources because of the way this content enriches their data-gathering efforts and advertising revenues (Bottando 25, 114). Because Google is an established, private institution with a profit incentive for becoming a go-to research hub, it is able to offer digitization services at a lower price and faster speed than other digitizers who might be bidding for a digitization contract (87). Yet because of this, the negotiating power is Google’s. The result is that publicly-funded agencies face pressure to limit public access in ways that work against their mandate to increase public access. When, for instance, Bottando was speaking to Patrick Bazin of the Bibliothèque Municipal de Lyon, a library that had partnered with Google, she asked whether he was in a position to give Google’s digital scans of his library’s public domain books to another institution (86). Bazin’s response: “No, because this is a partnership. Another institution could take this [these files] and it would hurt Google’s business model” (86). Libraries aren’t often in a position to demand that corporations grant them circulation rights over digitized resources with no strings attached. And so they compromise.

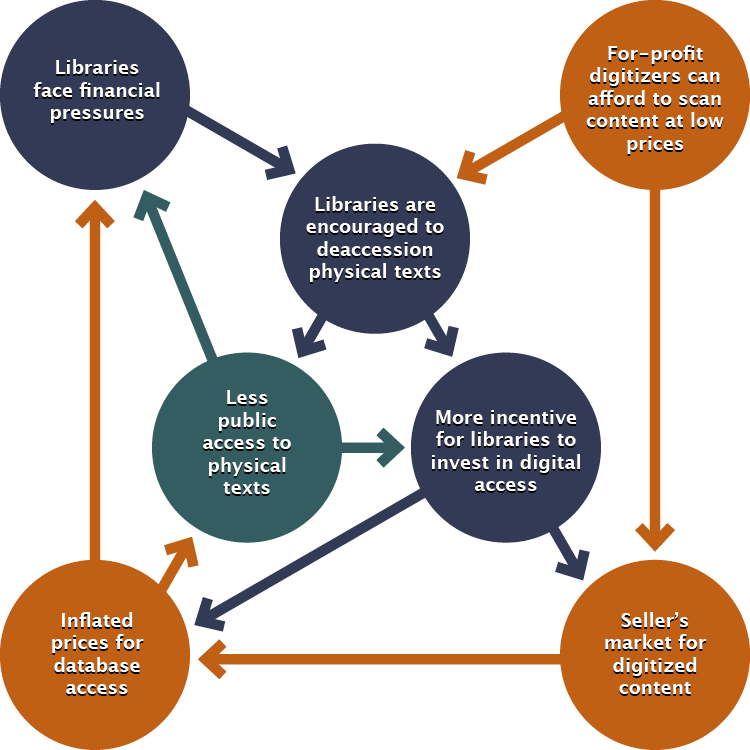

Faced with tight budgets and ever-increasing journal costs, libraries turn to digitization to preserve and circulate texts, a practice that allows them to host archives of fragile public domain texts off-site or deaccession them entirely.

Here’s the rub, however: when public institutions like the Bibliothèque Municipal de Lyon are not in a position to grant open access to the public-domain scans of their works and when those same public domain texts are becoming increasingly more difficult for the everyday person to access, for-profit institutions become the most robust sources of public domain scans. Organizations like ProQuest (which owns the British Periodicals Database beloved by Victorian print culture scholars) have a seller’s market for their resources. For a library that wants to provide users access to ProQuest’s content, high subscription rates become one of the financial burdens that drain money away from the library’s budget for stack maintenance. As a result, libraries have more incentive to jettison texts that are delicate or have low mainstream popularity.

Within Victorian studies, material culture scholars have called attention to digitization’s repercussions for our archive, lamenting this vicious cycle of high database prices and shrinking stacks. Andrew Stauffer distills these concerns especially poignantly, arguing that to reduce the number of physical nineteenth-century texts in circulation is to lose the opportunity to read these texts for traces of their own past audiences (340). The dedication on the flyleaf, the flowers pressed between pages, and the sewing needle stored in a book for safekeeping—we lose the lion’s share of these idiosyncratic traces when a few digital “surrogates” replace access to a much wider range of physical texts (336-37). The most strident skeptics of the digitization economy argue for material preservation, or at the very least, for the creation of high-quality and stable photographs of each individual text that is relocated out of the reach of archive visitors.

I’m persuaded by these concerns about the value of keeping a varied physical archive within reach of visitors, but I would also like us to think more strategically about access issues within the economic structures we cannot escape. It is an unavoidable truth that many libraries simply cannot afford to maintain collections of nineteenth-century texts if they even have them in the first place. Likewise, nor not all libraries are able to subscribe to repositories such as the British Periodicals Database. Although material copies of texts offer insights that cannot be gained through virtual surrogates, digitized primary source texts expand people’s ability to explore at least some of the material traces Stauffer and others describe. This is especially a boon for poorly-funded libraries or people who cannot travel to visit physical texts for any number of reasons—finances or physical ailments among them. More than this, with new digital platforms and soaring storage capabilities, we have the opportunity to develop new ways of thinking with readers’ material traces. Imagine, for instance, a platform that superimposed the marginalia from multiple copies of the first volume edition of The Woman in White! Imagine if libraries and individuals could contribute their scanned copies of the same edition for inclusion in the collection. What an interesting thing it would be to look at the patterns that might emerge in the margins…

Unfortunately, one of the things stopping us from exploring texts in this way is that the most centralized collections of nineteenth-century media exist behind paywalls that many students and scholars struggle to breach. Given what we know about the factors that foster or forestall access to institutions of higher education, we can see that the privatization of the public domain disproportionately restricts access to nineteenth-century primary sources for people who lack financial or institutional resources. It also confines a large proportion of our primary source encounters to the forms and platforms that publishers create rather than those that we design for our own research purposes.

Reading With The Basilisk: Primary Research in a Post-EULA Era

“But wait!” an imaginary choir of colleagues cries out. “Not all digitized texts are locked away in for-profit databases. Haven’t you heard of the HathiTrust Digital Library? It is a massive treasure trove! It is well-organized; it has permalinks; it is freely accessible and searchable online.”

The imaginary chorus is correct. The HathiTrust collection is a thing of wonder and beauty. It matters that it is freely accessible. It matters that it is stable. It is extremely important that it is so well-organized compared to other free archives of public domain content.

Yet I’m afraid that it is also the best example I can provide of a resource where all of the broad and troubling threads I’ve outlined in this chapter intertwine. HathiTrust may be an excellent resource for research, but it is hardly exempt from the profit motives and restrictive licenses that characterize much of the scholarly ecosystem today. It too has a role to play in redefining which nineteenth-century publications readers can most easily reuse in their work.

So far, I have suggested that corporate interest in commodifying access has changed our legal relationship to our primary and secondary sources. In my last section, I called attention to the statement that HathiTrust provides on its public domain texts that have been Google-digitized, noting that these texts feature the stern but ambiguous caveat: “Google requests that the images and OCR not be re-hosted, redistributed or used commercially.” I also explained that when it is attached to a public domain text, this firm but vague language is only persuasive in an environment in which organizations can legally impose restrictions on our public domain and fair use rights by using licenses as a precondition of accessing media. HathiTrust’s public-facing documentation does not make it clear whether Google is simply asking us to do it a polite favor or if its “request” has legal teeth.[9]

But to some degree, the precise meaning of the word “request” is irrelevant here. To achieve its desired effect, all Google needs to do is suggest that it might be able to leverage its lawyers against those who rehost or remix these scans. One reason for this is that when litigating licensing disputes in the United States, courts have generally supported companies who have sought to enforce “clickwrap” and “browsewrap” licenses (Clark and Chawner). Clickwrap licenses are the pop-ups that prevent you from using a service until you click “I have read and agree to the terms of use.” Browsewrap licenses are even more pernicious. In Michelle Garcia’s succinct explanation in the Campbell Law Review,” many Browsewrap contracts center on a “Terms of Service Agreement” whereby a user visits a website and by viewing the website, using the website or even just navigating to the website, the user agrees to be bound by the Terms of Service located elsewhere” (Garcia 35-36). Garcia points out the improbability of users actively consenting the these ‘agreements,’ noting that in some cases, the very act of navigating to the page on which the terms exist constitutes agreement with the terms (36). Whether or not Google’s “request” is a formal browsewrap license, it resembles one enough to stymie readers who encounter it.

What all of this suggests is that in our current information ecosystem, the very act of looking at some of our primary sources enters us into an implied legal contract not to use them in ways that would otherwise be protected by law. We can think of these scans as basilisk texts, objects that freeze us into inaction when we merely set eyes on them. These books also resemble basilisks in another sense: they are “monstrous hybrids” that disrupt our ability to create new works because of their twin pulls toward two different species of content– common and commercial property. Here I’ve slipped into another jargon, borrowing from the language of sustainable design. In sustainability discussions, the term monstrous hybrid refers to “a product, component, or material that combines both technical and organic nutrients . . . in a way that cannot be easily separated, thereby rendering it unable to be recycled or reused be either system” (“Monstrous Hybrid”). How like a text that we can peer at and link to, but not excise from its restrictive license without labor and expense.

The proliferation of basilisk texts has implications for how we interact with HathiTrust and other archives like it, potentially reducing the variety of texts we can ‘reuse and recycle.’ As one case in point, in a 2013 study, Alex Clark and Brenda Chawner sought to understand the influence of platform limitations and EULAs on the accessibility of digitized New Zealand public domain texts.[10] In their research, they selected one hundred public domain texts and searched or each of them in six repositories (Google Books, Hathi Trust, Internet Archive, Early New Zealand Books, New Zealand Electronic Text Collection, and Project Gutenberg,) turning to Google and Bing searches if they found no copies in these archives (Clark and Chawner). Their results give us cause for concern:

Out of a sample of 100 public domain books, only three are hosted by repositories that did not seek to restrict any form of subsequent use. Many repositories also impose significant barriers to access, with 48 percent (24) of all digitized books being hosted by at least one repository that restricts access. An exploratory study into the paid market for public domain books also revealed that 72 percent of digitized books within the sample are offered as paid downloads on at least one merchant Web site, with prices as high as US$9.99.[11]

Clark and Chawner found HathiTrust to be the most use-limited of the six repositories they used in their search. Out of the books surveyed, the authors found twenty-three in HathiTrust, but twenty-one of these—that is, 91% of the available HathiTrust texts—were restricted in some way. Restrictions included “[blocking] the cut and paste function, as well as the ability to download books as a single PDF file (a feature that is only available to users with login credentials from an institutional partner)” (Clark and Chawner). Like the proprietary platforms that ProQuest and other for-profit publishers impose over scholarly articles, HathiTrust’s default settings for some public domain texts restrict creative forms of reading and scholarship.

The main reason for these restrictions is that much of the public domain content in HathiTrust is limited by the terms and conditions imposed by digitizers like Google. This is not especially surprising: HathiTrust came into being as a response to Google’s library partnership program (Elkiss). Unfortunately, the ripple effects of HathiTrust’s content limitations may be significant. Libraries under financial pressures may choose not to shoulder the cost of digitizing a text before deaccessioning it based on the availability of other digitized copies online. In this environment, a high percentage of Google-digitized resources represents a low percentage of texts that allow for creative autonomy over the nineteenth-century public domain. The ‘monstrous hybrids’ that make up this archive can only be repurposed under very specific circumstances that are often difficult for students and researchers to navigate.

An Aside:

Anecdotally, as one component of my critical edition project, I attempted to locate unrestricted public domain scans of all of the primary sources I referred to in my work. This took a significant amount of time, and it was only partially successful. For example, HathiTrust includes multiple copies of the first volume edition of The Woman in White. Princeton’s copy is Google-digitized and thus use-restricted. Only one of the two copies from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign is listed as being unambiguously in the public domain.

I found that it was much easier to locate unrestricted copies of texts that are already well-known in Victorianist circles—multiple libraries were likely to have scanned and shared them under a range of licensing conditions. However, what eluded me were re-hostable versions of lesser-known works such as bowdlerized editions of Shakespeare. This was discouraging because texts like these seem uniquely ripe for student analysis. If students were creating an open-pedagogy project based on such texts, they would have ample opportunities to close-read two texts alongside one another as well as to contribute original research writing to the field. Yet content reuse restrictions make this adaptation process much more complicated.

If you’ve written an article or research paper that refers to multiple pre-1923 texts, I recommend looking for unrestricted copies of your sources as an exercise—it was eye-opening.

Scale and Scope: Where Do We Go From Here?

Another of Clark and Chawner’s findings brings this essay back to the place where it began: the intersections between localized media institutions and legal policies writ large. But while I began this work by inviting us to look at more localized policies in our scholarly communications landscape, this last finding pushes us to think in much bigger terms—in scopes that far exceed national boundaries.

As they searched for their public domain texts, Clark and Chawner were concerned to note that both Google and HathiTrust restricted New Zealanders’ access to many of them. The reason for this is that HathiTrust and Google have responded to different countries’ legal systems in excessively-conservative ways. In New Zealand, the authors note, public domain permissions begin 50 years after an author’s death (Clark and Chawner).[12] In an excess of caution, HathiTrust and Google limit New Zealand IP addresses to works for which 140 years have passed since publication or the author is known to be dead (Clark and Chawner). This is despite the fact that “a fifteen–year–old author would need to live beyond the age of 105 for copyright to last 140 years” (Clark and Chawner). The researchers pointedly note that seventy-seven of the hundred books in their study had identifiable authors, and it was possible to tell when the author had died for sixty-six percent of these books in one minute or less (Clark and Chawner). Yet, presumably because of the vast array of texts in these databases (and possibly the limited impact of country restrictions on profit,) the digitizers tended to leave this public-domain-identification step out of their process, simply limiting access by default. When Clark and Chawner looked for ways to let HathiTrust know that some of its scans could legally be displayed within New Zealand, they found that while provisions existed for reporting whether a copyrighted text is in the collection, HathiTrust and Google Books lack a “standardized procedure to report incorrectly restricted books” (Clark and Chawner).[13] Regardless of these corporations’ intentions, some of the most powerful and best-organized collections of primary sources respond to national policies at such a scale that significant swathes of the archive are artificially inaccessible to scholars working with digitized texts.

Let’s think about these findings in terms of participation in Victorian studies research. Does it not seem strange to you that in the age of digital publication and multinational corporate interests, I, as a scholar in the United States, have more access to many public domain texts written in other countries than those who work in those countries in the first place? What does it mean for nineteenth-century scholarship that this is the case? How do such dynamics shape who takes an interest in nineteenth-century literary culture or who can publish in our field?

Digging into the institutions and policies associated with scholarly publication and digitization raise these types of questions around every turn. Clearly, it is time for us to integrate attention to public access and stewardship of the public domain into our writing and teaching processes. Although we may not be able to reshape larger publishing systems single-handedly, we can take more intentional actions to confront the factors that reduce access in our field. By diversifying our efforts in a range of large and small ways, we may be able to shift the needle toward more inclusive access to our field’s conversations.

Ongoing Questions

What might this values-integration look like for us as researchers?

Perhaps it is time to read those insufferable terms of service agreements after all. We should raise our voices in protest when media providers—and especially those funded by institutions we work within—demand that we relinquish our rights to fair use. We should also find ways to contribute to others’ knowledge in our field by intervening in the digital archive, providing unrestricted public domain scans where possible and pressuring digitizers to do the same. Where multiple archived scans of a primary source exist, we can choose to link to unrestricted public domain scans over ‘basilisk texts.’

Within this project, I have tried to reflect these values by taking the time to search for unrestricted public domain scans and open-access versions of each of my cited articles. Where possible, I have cited these in lieu of more restricted content.

What might this look like for us as writers?

Perhaps it means acknowledging our own positionalities within broader educational systems. We need to understand that not all of our peers who are interested in studying the long nineteenth century can do so on equal terms. Depending on where and who we are, some folks can participate more than we can, others less. We should recognize the power structures that make it riskier for some participants in the academy to choose how they publish than others. As we identify our own privileges within this system, we should leverage them to address the power imbalances in our disciplines.

One strategy for doing this is for those of us with stable employment to be more selective about the journals we choose to publish in, incorporating open-access publication into our personal categories for success. Another is to draw upon our social networks and encourage influential journals to shift to open-access publishing models. Where open-access publishing isn’t possible, we should become familiar with journals’ attitudes toward self-archiving, towards preprints, and towards postprints.

Within this project, I have tried to reflect these values by exploring circulation options for my work that are not under paywall. My institution provides instructions that say that we ought to deposit completed dissertations to Gale-Cengage’s ProQuest database, and while the repository does now offer the option for people to publish their dissertations OA by paying the company more money, I have viewed it as my duty to research all of my options. Among the hidden labors of this project are the hours I have spent researching UW-Madison’s open repository involvement and seeking information from the graduate school about exceptions to the ProQuest policy. Spoiler: as of 2019, there aren’t any exceptions to the ProQuest policy.

What might this look like for us as educators?

Perhaps it means recognizing that teaching students how to do the work of literary studies also means teaching them how to navigate our beleaguered archives. It means telling them about tools like UnPaywall or the Open Access button, resources that allow internet users to identify versions of scholarly texts that are not locked away within a proprietary database. It means striving to provide legal access to affordable learning materials when possible, recognizing that this makes the most difference to students with the largest financial burdens. It also means paying very careful attention to the tools we bring into our classrooms and how they shape how our students interact with our archive.

Within this project, I have sought out platform providers who have demonstrated a commitment to student privacy, ethical uses of data, and open-source infrastructure, namely Pressbooks, H5P, and Hypothes.is. I have also ensured that readers have multiple modes of accessing my project. Recognizing that different media formats provide different affordances, I have ensured that users may access this project via a web browser as well as offline in the form of an ebook reader file or printable PDF document. In the portion of this text that addresses learners, I have also provided instructions about how to access open versions of academic texts.

In the spirit of reducing potential barriers to the redistribution and remixing of my work, I have appended licenses to each project section that are as open as my institutional context will permit. As soon as I am able to do so without risking the ability to deposit this dissertation with my institution, I will change my projects’ license designations from CC-BY-NC-ND to CC-BY, the Creative Commons license that permits the most forms of reuse while still requesting that others provide attribution statements to accompany adapted versions of this work.

In The Woman in White: Grangerized, I have also composed a research resource for students in order to outline the strategies they can use to locate paywalled resources through legal channels.

Works Cited

“Annual Report for Fiscal Year Ended Mar. 31, 2018.” Cengage Learning Holdings II, Inc. https://assets.cengage.com/pdf/Annual-Report-Fiscal-Year-Ended-March31-2018.pdf. Permalink: https://perma.cc/N73N-ZSC7.

Bergstrom, Theodore C., Paul N. Courant, R. Preston McAffee, and Michael A. Williams. “Evaluating Big Deal Journal Bundles.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 111, no. 26, July 2014, p. 9425, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403006111.

Bottando, Evelyn. “Hedging the Commons: Google Books, Libraries, and Open Access to Knowledge.” Ph.D. (Doctor of Philosophy) thesis, University of Iowa, 2012. http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd/3265.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. “College tuition and fees increase 63 percent since January 2006.” The Economics Daily, 2016, https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2016/college-tuition-and-fees-increase-63-percent-since-january-2006.htm. Permalink: https://perma.cc/UBK8-LJDP.

Cassuto, Leonard.The Graduate School Mess: What Caused It and How We Can Fix It. Harvard University Press, 2015.

Clark, Alex, and Brenda Chawner. “Enclosing the Public Domain: The Restriction of Public Domain Books in a Digital Environment.” First Monday, vol. 19, no. 6, May 2014. journals.uic.edu, doi:10.5210/fm.v19i6.4975. Permalink: https://perma.cc/4B6R-GBZS.

“Copyright Review Program.” HathiTrust Digital Library, https://www.hathitrust.org/copyright-review. Permalink: https://perma.cc/GJL4-AY7X.

Cronin, Catherine. Openness and Praxis: A Situated Study of Academic Staff Meaning-Making and Decision-Making With Respect to Openness and Use of Open Educational Practices in Higher Education. 2018, PhD Dissertation, National University of Ireland–Galway. http://hdl.handle.net/10379/7276. (CC-BY-NC-ND)

“Datasets.” HathiTrust Digital Library, https://www.hathitrust.org/datasets. Permalink:https://perma.cc/UJ5S-NWAS.

Elkiss, Aaron. “Beyond Google Books: Getting Locally-Digitized Material into HathiTrust.” HathiTrust Digital Library. https://www.hathitrust.org/blogs/perspectives-from-hathitrust/beyond-google-books-getting-locally-digitized-material-hathitrust. Permalink: https://perma.cc/7TUE-9J9D.

Elsevier Subscription Agreement 2014-2018, University of California. University of California Big Deal Contracts With Publishers, edited by Ted Bergstrom, http://faculty.econ.ucsb.edu/~tedb/Journals/BigDeals/UCalifornia/. Permalink: https://perma.cc/WRB9-NAKU.

Felluga, Dino Franco. “Addressed to the Nines: The Victorian Archive and the Disappearance of the Book.” Victorian Studies, vol. 48 no. 2, 2006, pp. 305-319. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/vic.2006.0078

Fu, Tao, and Kavita Karan. “How big is the world you can explore? A Study of Chinese College Students’ Search Behavior Via Search Engines.” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 174 (2015): 2743-2752. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.961. (Open publication: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Garcia, Michelle, “Browsewrap: A Unique Solution to the Slippery Slope of the Clickwrap Conundrum.” Campbell Law Review, vol. 36, no. 31, 2013, pp. 31-74, https://ssrn.com/abstract=2409235.

Karaganis, Joe. “Access from Above, Access from Below.” Shadow Libraries: Access to Knowledge in Global Higher Education, edited by Joe Karaganis, MIT Press, 2018, pp. 1-25. (Open publication: CC BY-NC 4.0; PDF download: https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/shadow-libraries).

Kell, Gretchen. “Why UC Split with Publishing Giant Elsevier,” Berkeley News, 28 February 2018, https://news.berkeley.edu/2019/02/28/why-uc-split-with-publishing-giant-elsevier/. Permalink: https://perma.cc/MY5D-EZM6.

Kenneally, Michael E. “Commandeering Copyright.” Notre Dame Law Review, vol. 87, 2012 2011, pp. 1179–1244, https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr/vol87/iss3/6.

McGuire, Hugh, Boris Anthony, Zoe Wake Hyde, Apurva Ashok, Baldur Bjarnason, and Elizabeth Mays. “Considering Publishers” and “Considering Librarians.” An Open Approach to Scholarly Reading and Knowledge Management, Rebus Foundation, 2018. https://press.rebus.community/scholarlyreading/.

“Monstrous Hybrid.” Sustainability Dictionary. Presidio Graduate School, https://sustainabilitydictionary.com/2005/12/03/monstrous-hybrid/.

Morrison, Heather. “Economics of Scholarly Communication in Transition.” First Monday, [S.l.], May 2013, https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/4370/3685. Date accessed: 03 Mar. 2019. doi:https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v18i6.4370.

“Open-Access Strategy Manager.” Elsevier, https://4re.referrals.selectminds.com/elsevier/jobs/open-access-strategy-manager-21906, retrieved 3 March 2019. Permalink: https://perma.cc/Z86V-6FT5.

“Open-Access Strategy Manager – CrowdLaaers.” CrowdLaaers(Hypothes.is Annotation Aggregator), https://crowdlaaers.org/?url=https://4re.referrals.selectminds.com/elsevier/jobs/open-access-strategy-manager-21906. Accessed 5 March 2019.

Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI). “China Is Now Blocking All Language Editions of Wikipedia.” https://ooni.torproject.org/post/2019-china-wikipedia-blocking/. Accessed 17 May 2019. Permalink: https://perma.cc/E8EA-NUC9.

Posada, Alejandro, and George Chen. “Inequality in Knowledge Production: The Integration of Academic Infrastructure by Big Publishers.” Leslie Chan; Pierre Mounier. ELPUB 2018, Jun 2018, Toronto, Canada. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01816707. [CC-BY 4.0]

Rosenblatt, Elizabeth L. “The Adventure of the Shrinking Public Domain,” University of Colorado Law Review vol. 86, no. 2, 2015, pp. 561-630. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/ucollr86&i=591.

“Software License Agreement: Adobe Digital Editions 4.5.10.” Adobe. Archived PDF export: https://wisc.pb.unizin.org/app/uploads/sites/362/2019/03/Install-Adobe-Digital-Editions-4.5.10.pdf, downloaded 5 March 2019.

Wagstaff, Steel. “Open Content Deserves Open Platforms: Using Open Source Tools to Publish Openly Licensed Books & Interactive Learning Material.” “E”ffordability Summit, 27 March 2019, Memorial Student Center, Menomenie, WI, Conference Presentation.

Stein, Bob. “Reading and Writing in the Digital Era.” Discovering Digital Dimensions, Computers and Writing Conference, 23 May 2003, Union Club Hotel, West Lafayette, IN. Keynote Address.

Zhi-Jin, Zhong, Tongchen Wang, and Minting Huang. “Does the Great Fire Wall Cause Self-Censorship? the Effects of Perceived Internet Regulation and the Justification of Regulation.” Internet Research, vol. 27, no. 4, 2017, pp. 974-990. ProQuest, doi: 10.1108/IntR-07-2016-0204.

- For reference, Larivière et al. point out, in 2014, pharmaceutical giant Pfizer had a 42% profit margin (10). They add that several of the big five publishers had profit margins above the "Industrial & Commercial Bank of China (29%) and far above Hyundai Motors (10%), which comprise the most profitable drug, bank, and auto companies among the top 10 biggest companies respectively" (Larivière et al. 10). ↵

- The Bureau of Labor Statistics website features an interactive version of the graph below as well as a machine-readable table of chart data. ↵

- Later in this project I will outline ways for humanities scholars to actively improve platforms for reading and writing even if those scholars do not have coding skills. To support my case in the present moment, I'll simply quote from the "Restrictions and Requirements" section in the Software License Agreement for Adobe Digital Editions, the platform of choice for ProQuest's Ebook collection as of 2019. Item 4.2 in the agreement states: "Customer agrees that it will not use the Software other than as permitted by this agreement and that it will not use the Software in a manner inconsistent with its design or Documentation." Item 4.3 states: "Except as expressly permitted in Sections 2 or 16, Customer may not modify, port, adapt, or translate the Software." In other words, no one is allowed to improve upon the current design by adding additional functionalities without Adobe's permission. Item 4.4 warns against reverse engineering: "except as otherwise expressly permitted in Section 16.1, Customer will not reverse engineer, decompile, disassemble, or otherwise attempt to discover the source code of the Software." Translated: don't try to get into Adobe Digital Editions's code, and absolutely don't borrow code snippets to use in other projects ("4.5.10 Software License Agreement"). This exists in stark contrast to the open-source ethos that fuels many software projects online. ↵

- Some people occupy more than one of these designations at once, of course. ↵

- This number is interesting in part because the University of California system has historically done an excellent job of negotiating their contract down from what Elsevier proposes for them. In contrast with Elsevier's traditional 5% price increase policy for R1 institutions, the university was able to reduce their yearly increase rate to about 1.5% by 2013, a rate that was to increase to about 3% by 2018 (Bergstrom et al. 9429, "Elsevier Subscription Agreement" 8). According to Bergstrom's estimations, "If they had acceded to Elsevier’s requests for annual increases of 5%, their annual subscription price in 2013 would have been nearly $13 million instead of the $9.3 million that they contracted to pay in 2013" (9429). ↵

- Some states require publicly funded agencies to disclose information about their financial contracts upon request, effectively restricting publishers' ability to require that libraries sign nondisclosure agreements. This is why we are able to dig deeper into the kinds of costs and restrictions associated with the University of California system's Elsevier contract for the previous four years. ↵

- The actual posting does not include a date, but Google's first cache of the posting appeared on March 2, 2019 at 17:49:40 GMT. ↵

- An active discussion emerged in the margins of the job posting as Hypothes.is annotators critiqued the description. Due credit goes to annotators danamcfarland, ShorterPearson, and actualham for their close-readings of this posting, and especially Dana McFarland for questioning the commercial credentials requested in the post ("Open Strategy Manager - CrowdLaaers"). ↵

- Digging into HathiTrust's "Datasets" page does yield some results, informing us that many "volumes were digitized by Google and are available through an agreement with Google that must be signed on the behalf of researchers by an institutional sponsor" under the conditions that they "(1) can only be used for scholarly research purposes, (2) May not be used commercially, (3) May not be re-hosted or used to support publicly available search service, and (4) May not be shared with third parties," but this hardly clarifies what would actually happen to me if I were to remove the Google Watermark from a Victorian advertisement and include the image in this project. ↵

- Clark and Chawner also provide an illuminating overview of some of the legal conversations related to copyright and the public domain in both the United States and New Zealand. Their article, "Enclosing the Public Domain," is worth reading for those interested in a more detailed and less US-focused account of the publishing landscape. ↵

- The study's findings reflect a combination of licensing restrictions directed toward all internet users who seek to access their sample text and New-Zealand-specific public domain law. This means that if you were to replicate their study in the United States, Britain, or Europe, some of your percentages of accessible texts might be different. However, both the study's generalities and particulars are of significance to humanities scholars regardless of the countries in which they work. ↵

- This number is somewhat generous in comparison to many other countries' allotment of 70 years after the author's death (Clark and Chawner). ↵

- HathiTrust, at least, has been working to identify public domain texts from 1870-1949 within its collections, an effort that has resulted in 314,398 additional texts from the UK, Canada, and Australia being re-labeled as public domain resources between 2008-2018. This work continues thanks in large part to grant funding ("Copyright Review Program"). ↵

The Higher Education Funding Council (HEFC) and Research Councils UK (RCUK) have combined as of April 2018 - UK Research and Innovation.

Abbreviation for "open access"

I use the term 'scholarly community' to describe people who are active participants in scholarly discussions in a range of formal or informal contexts. This includes--but is not limited to--researchers, instructors, and students affiliated with a higher education institution.

DRM is an abbreviation of"digital rights management." DRM technologies "limit what a reader can or cannot do with a given work" (For more detailed information, see "Considering Publishers" in McGuire et al., "An Open Approach to Scholarly Reading and Knowledge Management.")

"FOIA" is an abbreviation for the Freedom of Information Act. In some states, public institutions are required by the state to reveal the details of their commercial contracts when asked.