A Field and Its Forms

Where We Stand: This Project’s Core Beliefs About 19th-Century Studies

In the following pages, I argue that the most compelling reason to study the long nineteenth century is not the specific works published during that period of time, but rather, our current orientation toward the nineteenth-century archive. Put a different way: our current relationships to long-nineteenth-century texts—as well as to current-day patterns of technological change and global capitalism—make it possible for researchers and instructors to do more with Victorian media and to reflect differently on our own information ecosystems than many other archives permit.

We have the ears and the interpretive tools to identify whose voices our institutions are leaving out. What we need is to use these tools to resituate our own writing and teaching within those institutions.

Having outlined a series of motivating conversations about how audiences participate in scholarly communities, I’d like to return once more to my claim that strategic presentists should be devoting more attention to the present-day affordances of the long-nineteenth-century archive as such when they make a case for the broader relevance of our subdiscipline.

This is an expansive stance, so let’s break it down into separate parts.

PART 1: The Victorian Print Culture Surge Enriches Our Present-Day Archive

The long nineteenth century was a time of rapid technological and social change, and this led to a print culture “boom” that expanded the scope of the materials and nineteenth-century reflections about reading culture that we are able to examine in our own work.

During the 1800s, printed texts became much more affordable, prevalent, and accessible to people across a wider range of social classes than had been the case in past centuries. In Britain, literacy rates increased, railroads and the invention of the telegram changed the speed and frequency of communication, the concept of professional authorship gained traction, and new ways of cataloging and legally defining media began to crystallize. If in long-past eras, books were precious objects to be chained to library tables and limited to the elite, nineteenth-century books could be accessed through a library subscription at unprecedentedly low prices, purchased in penny installments, picked up in railway bookstalls, used as a vehicle for love-notes, or even torn up and used as kindling.[1] Reading practices are always shaped by conventions that affect how people put texts to use. In the Victorian period, disparate interpretive strategies and institutions emerged as technologies expanded. A more-widespread circulation of texts at multiple price points allowed readers to develop a more varied, personalized, and socially integrated range of interactions with literary texts.

These rapid changes in print production, circulation, authorship, and reader interaction practices during the mid-nineteenth century mark what we would now call a period of “media in transition.” Participatory culture scholar Henry Jenkins defines this phenomenon as “a phase during which the social, cultural, economic, technological, legal, and political understandings of media readjust in the face of disruptive change” (Convergence 289).[2] Such periods of readjustment often inspire writers to map out contrasting beliefs about the past and future of cultural institutions—what they were transitioning from and to. Because more people were empowered to read and write about such changes during the long nineteenth century, we have access to a wider range of perspectives to draw from in the printed matter that survives today. Preserved and digitized texts, as well as our own research processes, are inevitably biased toward dominant and privileged perspectives,[3] but the sheer proliferation (and comparative democratization) of this media still gives us more artifacts to think with than we can access for many earlier periods.

PART 2: Public Domain Texts Foster Innovative Scholarship

Because the surviving nineteenth-century media archive is both massive and in the public domain, scholars can interact with this archive in a wider range of ways than it is possible for us to do with many other historical archives.

Victorian texts occupy something of a sweet spot where preservation and accessibility are concerned. It is expensive to preserve physical media, and forces such as mold, fires, and Victorians’ tendencies to repurpose written books have caused a large number of texts to be lost to us. Many artifacts that have survived are prohibitively difficult to access or digitize. These challenges apply to many texts in the Victorian period, but thanks to the print boom, we are more likely to have multiple surviving copies of published texts to work from as we research. For example, if the sole existing copy of a 13th-century manuscript has a worm-eaten page, contemporary scholars must rely on context cues to fill the gaps. In contrast, if a grub devours a section of our copy of Dickens’s 1836 Pickwick Papers, we can look up multiple digital scans of the serial and volume publication of these tales. Added to this, many editions of novels published during and after an author’s life include different wordings, chapters, illustrations, or bowdlerizations; these are yet more interesting developments to think with.

International copyright policies in the present day also make long-nineteenth-century media easier to access and analyze than is the case for many texts published in more recent years. Thanks again to the Victorian print boom, we have access to a large swath of published media from the period that falls within the protections of the public domain.[4] In the United States, the practice of re-using media for the purpose of teaching, commentary, scholarship, or creative transformation may be loosely protected under the terms of “fair use,” but in practice, fair use is vaguely defined and poorly defended.[5] In contrast, when a work is in the public domain, others have the legal right to republish, reuse, or modify it in any way they see fit, with or without attribution. In other words, people working with pre-1923 materials don’t have to worry as much about defending their use within a US system that interprets fair use on a case-by-case basis.[6] This allows us to do innovative and experimental things with large numbers of texts, such as running thousands of novels through digital analysis applications and exploring the patterns that arise among them.[7] Likewise, we can playfully modify nineteenth-century texts and printed images for a range of purposes—simple entertainment-value among them!

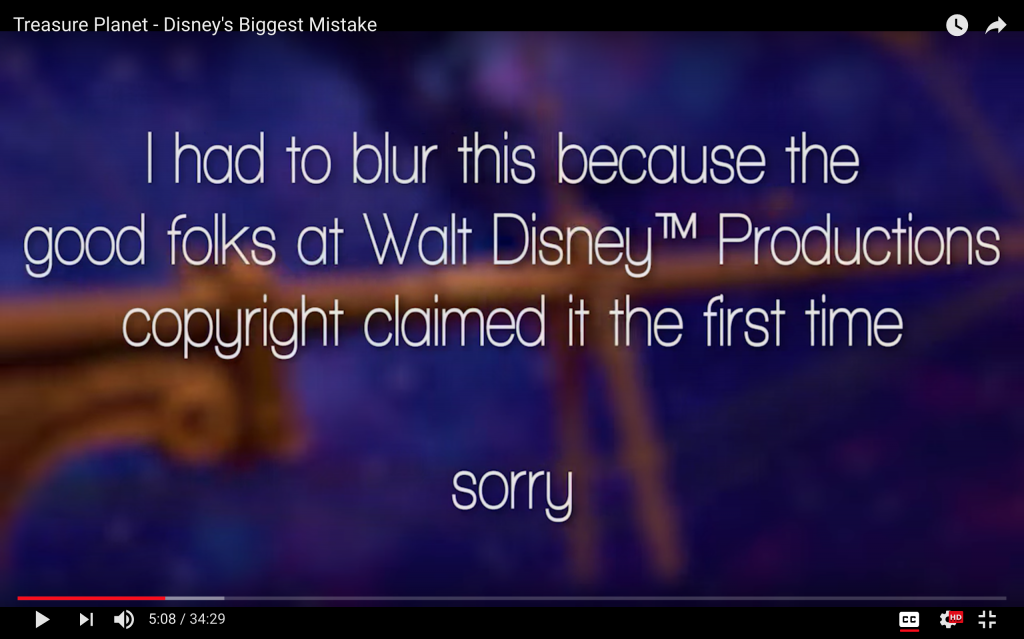

Compare, for instance, these two images.

Image 1

Image 2

The first image is a screenshot from a video essay that a Youtube creator named Breadsword painstakingly put together to critique the Disney film Treasure Planet. Because Disney issued a takedown notice, the author had to remove their initial video and alter its contents.

By way of contrast, the second image is a cheerful mishmash of separate public domain illustrations from the nineteenth century. This second image is infinitely more open to creative engagement than the copyrighted images hidden behind Breadsword’s apology statement. Working with these public domain images, the world is my oyster. If I wanted to include this image in the publication you’re reading right now, I could build the case that my creation and recirculation of the second collage is fair use because the image appears in a scholarly essay and plays a purposeful role in this work. I could insist that the book-hungry tiger is a visual metaphor for Victorian readers’ voracious enthusiasm for texts. I could say that this image is a reference to corporations’ hunger for the profits to be gained from nineteenth-century media and current-day scholarly production alike. I could use it as a flippant description of my own research process, which sometimes produces intellectual appetites I don’t understand until they have run their course. Or I could simply say “I made this image hybrid on a whim. It has no special significance for this project.” And while this might show questionable judgment, it would be legally unimpeachable.

Admittedly, this image pairing does not convey a simple contrast between the license to adapt media and lack thereof: we can still raise multiple questions about privilege and differing interpretations of transformative use. (Would Disney’s representatives have felt as much license to send—or would this Youtube creator have felt that he had the ability to formally protest—the takedown notice had Breadsword been identified as a university-sanctioned scholar? Would the kinds of alteration at play in the collage cause the image to pass a fair use assessment more easily than Breadsword’s use of the clip may have done?) However, even if we were dealing with two uses of the same media form—(film or collage)—I would likely only need to justify my use in the US if I were thinking about material published after 1923.

My point is that the acknowledged public domain status of the images I used for my own tiger adaptation requires me to expend less effort defending my use as fair use than would be the case if my archive were composed of more recent publications.[8] Both Disney and I benefit from public domain permissions in this situation, as Disney’s Treasure Planet is itself a retelling of a Victorian novel: Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island. Far from paying royalties, neither Disney nor I even face pressure to credit the original authors or illustrators who produced our 19th-century texts. Yet Disney can attempt to police others’ commentaries about its recent work based on a US legal system that has more language and precedent for punishing copyright violators than protecting fair use (Mazzone xi).[9] We live in a time when fair use principles are effectively broken thanks to justified anxieties about litigation. However, when working with artifacts in the public domain, Victorianists have opportunities for creative application and experimentation that would be more difficult to pursue if other players had copyright over our subject matter.

PART 3: The Openness of Our Archives Affects the Inclusivity of Our Disciplines

Factors that reduce access to disciplinary archives disproportionately exclude people who have limited material resources or institutional capital. A more-accessible archive expands opportunities for people to participate in our fields.

In research contexts, the ability to work with materials depends on having the financial, institutional, political, and social capital to access and legally use that material in some form. For instance, not all scholars are able to obtain research funds to visit their primary sources in a historical society or to pay permissions fees to reproduce media in their publications. And, as I’ve implied in my discussion of Breadsword’s video, not all commentators are equally able to obtain the legal guidance about copyright or the institutional support that can help them make a formal case for their fair use should a concern arise. Corpora thus serve as aggregators of privilege within specific fields, elevating the voices of people best positioned to work with the most compelling artifacts. Specialty areas that present a more level playing field for access to the primary and secondary sources at the heart of their conversations have the potential to be more inclusive than others.[10]

The openness of our archive also has implications for those of us who teach with texts from the long nineteenth century: our students have opportunities to engage with materials that may not have come to the attention of a wider scholarly community. By pursuing original research about lesser-known texts, students are able to participate in authentic learning activities and see themselves as active contributors to the discipline. Providing students with the chance to claim authority over some aspect of the archive is a powerful tool for student engagement that we should not take for granted.

To be sure, there is nothing inauthentic about inviting students to engage with a well-trodden archive. As our theoretical conversations shift, so too do opportunities to think with long-studied texts in new ways: the field renews itself. However, when faced with the challenge to compose ‘original’ work about canonical resources, the weight of existing commentary can lead many students to feel as though the best that they can do is to retrace others’ footsteps. This is compounded by the fact that emerging scholars don’t always have the same level of familiarity with the discussions that have come before them as do long-time participants in these discussions. Even if a student pens an entirely new and productive reading of Middlemarch, their experience may feel the same to them as it would if they had interpreted the text in ways that experts view to be deeply conventional.[11] There are still good reasons to assign essays on Middlemarch, but there is a value for writers and facilitators alike in creating opportunities for students to explore ‘new’ territories as well.

Here’s where we’re back in the world of open pedagogy. Consider how the conversation can change when we change the task and potential audience for a guided project in the humanities. Many courses in the present day culminate in what David Wiley refers to as a “disposable assignment”—a research paper or persuasive close reading that enters the Learning Management System and never leaves it, save perhaps for an evaluatory review by the instructor and (one hopes) a cursory glance by students once their grades have been posted (“What is Open Pedagogy?”)[12] If instead, students work together to compose a resource that has a life outside of the classroom, the instructor becomes a facilitator whose goal is to support students in communicating their work rather than primarily taking on the role of arbiter-assessor. If these students are working on a lesser-known portion of the archive, they’re faced with a genuine need to do the kind of background research into their texts’ social contexts that will help their audience grasp their arguments. This serves as excellent practice for the work that many established scholars do in the discipline. It also gives students the opportunity to develop arguments about a text’s broader significance by synthesizing existing conversations in the field. And, if students are willing to share the products of their work openly, they can also view themselves as scholars who increase others’ ability to access Victorian Studies.

PART 4: Our Research Processes Provide Insights About Current-Day Media Infrastructures and Economies

Our archive can help us see how contemporary media practices—especially our scholarly and teaching practices—are taking on new meanings as technologies and institutions change around us. Digital and legal factors that limit the use of public domain resources shed light on larger information access issues.

On its surface, the legal construct of the public domain is simpler than the legal construct of fair use.[13] But as the long nineteenth century teaches us, when technologies change, new media affordances emerge and new communities form around these affordances. In turn, because these affordances and communities are commodifiable, new disputes emerge about who has the right to use and profit from these media.

Let’s consider an example of these economies in action:

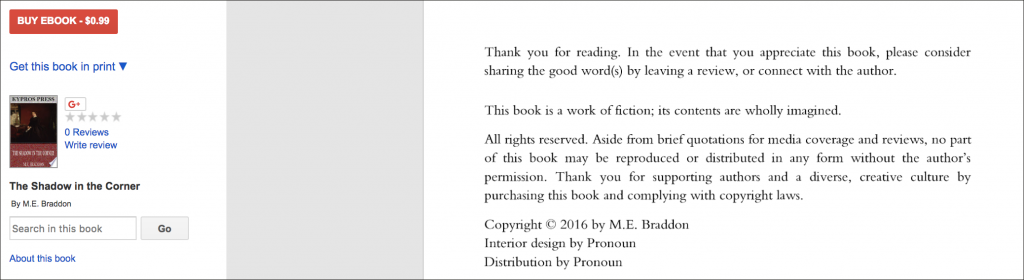

This screenshot features a Google Books listing of Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s 1879 story “The Shadow in the Corner.” In an unintended appeal to the few Braddon fans who happen to be ghost-whisperers, the seller claims that Braddon’s copyright is active as of 2016 and encourages readers to connect with the author to express their appreciation.

Here’s where we can put on our Critical Information Studies hats to explore this statement’s context and potential impact. While selling a text that is in the public domain is completely above-board, this publisher’s attempt to limit others’ rights to do the same with that text is not. This digital artifact is clearly the product of an ebook-on-demand industry that has grown so cheap and efficient that the accuracy of copyright pages isn’t of concern to the gatekeepers at Google Books.[14] It is also possible that no deliberate falsehood was intended: the Braddon cover page may have auto-generated by a computer program, and this ebook may simply be too minor a piece in a larger collection of digitized texts for the producer to feel like customizing appropriately. Regardless of intention, however, it is striking to see such an ardent appeal to readers to respect a fraudulent copyright claim and to think about how different audiences might respond. It is also striking to see this text indirectly authorized by Google, who may well get a small share of this text’s proceeds.

While we’re on the subject of Google, let’s look at an example of the tech giant’s own messages to its readers:

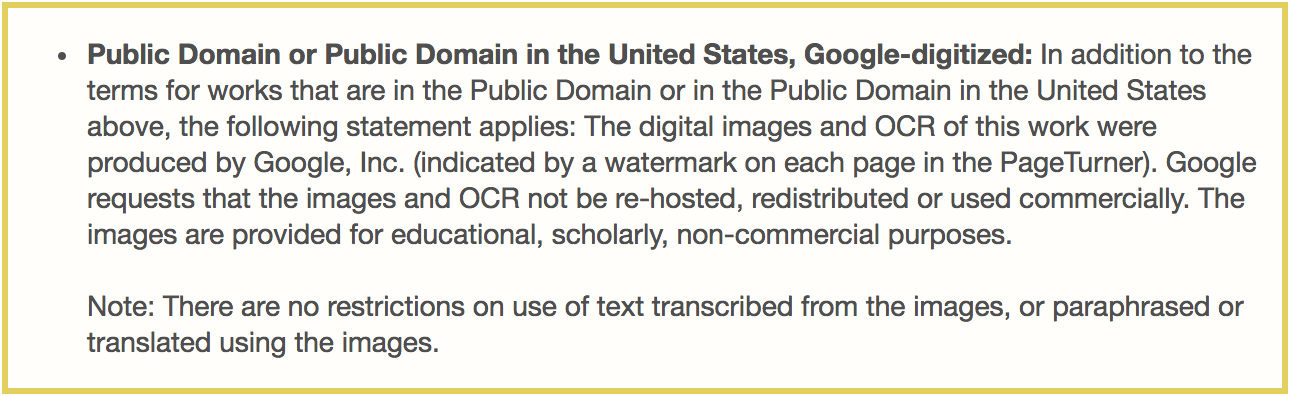

This statement appears on the usage guidelines page for the HathiTrust Digital Library, a treasure-trove of scanned primary texts that draws its collection from a range of libraries and archives, many of them publicly-funded. A huge percentage of the nineteenth-century texts in this collection are designated as “Public Domain, Google Digitized.”

But what does the sentence “Google requests that the images and OCR not be re-hosted, redistributed or used commercially” actually mean? Does Google think it is acceptable for me to re-host the images if I do so non-commercially, or is “used commercially” simply the last item in a list of prohibited acts? Textbooks are educational—can a commercial textbook feature a photo of Jane Eyre’s Google-watermarked cover page? Journals are scholarly, but they are also big business—would Google want Elsevier to profit from an article that features one of these image scans? Is it asking for a cut?

More importantly, if this text is in the public domain and I’m writing in the United States, should I care what Google would prefer I—or my students—do with these scans? Is Google’s request even legally binding? One of the clearest precedents we have for questions like this is a 1999 U.S. ruling that reproductions that are intended to ‘faithfully’ depict an art object or text in the public domain are also in the public domain (Stokes 136).[15] In theory, then, this ownership claim should be just as spurious as that of the sketchy Google ebook-seller we’ve just discussed. But what does it mean for Victorian Studies if Google’s request is legally binding?

Alternatively, what does it mean if it isn’t binding but we—or other scholars and students—believe that it is? Or if it isn’t binding but university representatives or publishers encourage us to leave the reproductions out of our work just to be on the safe side?[16]

Because so many nineteenth-century texts are in the public domain, questions about the worth of an author’s creative productions aren’t at the forefront of our decision-making about media reuse. Thus, we are better positioned to spot ambiguous rhetorical strategies like Google’s or attempts to redefine what a “faithful” reproduction means. Put differently, if Barthes’ figurative “death of the author” helped to reshape the way we think about our methods, in today’s environment, the fact that our authors are literally dead can help us understand how larger institutions affect access to those authors’ texts.

To torture yet another critical phrase, the medium is the message, but the mess left on our hands when we work with that medium is also the message. If scholars don’t pay attention to that mess now, our field’s ability to welcome a wider and more diverse range of participants into our conversations will suffer for it. This vigilance is the work of Victorian Studies too.

As we move forward, it’s time to ask where we should direct this vigilance, and one answer is the scholarly publishing industry many of us participate in as a precondition of academic employment.

Works Cited

Bernstein, Susan David, and Catherine DeRose. “Reading Numbers by Numbers: Digital Studies and the Victorian Serial Novel.” Victorian Review, vol. 38, no. 2, 2012, pp. 43–68. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23646683.

Breadsword. “Treasure Planet: Disney’s Biggest Mistake.” Youtube, 2017, 5:00, https://youtu.be/b9sycdSkngA?t=299.

Griest, Guinevere L. Mudie’s Circulating Library and the Victorian Novel. Indiana U P, 1970.

Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York U P, 2006.

Jhangiani, Rajiv. “Open Educational Practices in Service of the Sustainable Development Goals.” Open Con, United Nations Headquarters, New York, 2018. Recording and transcript: http://thatpsychprof.com/open-educational-practices-in-service-of-the-sustainable-development-goals/. Permalink.: https://perma.cc/9ENN-PEQE.

King, Andrew, and John Plunkett, editors. Victorian Print Media: A Reader. Oxford University Press, 2005. OCN: 173282894.

Mazzone, Jason. Copyfraud and Other Abuses of Intellectual Property Law. Stanford Law Books, 2011.

“More Information on Fair Use.” U.S. Copyright Office, updated December 2018, https://www.copyright.gov/fair-use/more-info.html. Accessed 9 Mar. 2019. Permalink: https://perma.cc/TSU5-KQZM.

Petri, Grischka. “The Public Domain vs. the Museum: The Limits of Copyright and Reproductions of Two-Dimensional Works of Art.” Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies, vol. 12, no. 1, Aug. 2014, p. Art. 8. www.jcms-journal.com, doi:10.5334/jcms.1021217.

Stokes, Simon. Art and Copyright. Oxford U P, 2001.

Trettien, Whitney Anne. “A Deep History of Electronic Textuality: The Case of English Reprints of Jhon Milton Areopagitica.” Digital Humanities Quarterly vol. 7, no. 1, 2013, pp. 2-28.

Wiley, David. “OER-Enabled Pedagogy.” Open Content, 2 May 2017, https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/5009. Permalink: https://perma.cc/RZ8V-K4LE.

—. “What Is Open Pedagogy?”Open Content, 21 October 2013, https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/2975. Permalink: https://perma.cc/ZY3Q-CMYV.

- As Guinevere Griest reports, the price for a library subscription at a circulating library could be a guinea a year, which was considered to be within middle-class readers' means (17). Circulating libraries could even serve as brokers for book ownership: “since the average Victorian reader seldom bought a three-decker until he had sampled its worth at the circulating library, and since Mudie could easily afford to slash prices well below the 31s.6d. asked for new three-volume novels, the book-selling department was an important section" (29). ↵

- Less formally but more charmingly, Andrew King and John Plunkett refer to this as a time of "mediamorphosis," crediting Roger Fidler for the term (Victorian Print Media 1). ↵

- This is a claim I will revisit in subsequent sections of this project. ↵

- In many countries including our own, questions of the public domain get muddier when we deal with manuscripts or three-dimensional works of art—however you choose to split hairs around those categories. For a haunting dive into these legal battles, see Griska Petri’s “The Public Domain vs. The Museum.” ↵

- Jason Mazzone’s Copyfraud unpacks how U.S. legal systems do more to punish individuals who violate terms of copyright than to punish corporations who restrict or threaten individuals’ fair use. ↵

- Here, unfortunately, I am best able to speak for scholars in the United States. I considered including representative examples of other countries' policies around scholarly use of copyrighted materials. However, rules of this type are often so complex that even my statements about American copyright, fair use, and public domain landscape are necessarily imprecise. The choice of which 'representative' examples from other countries to include seemed just as fraught with value judgments as speaking primarily from a US perspective did. My invitation, then, is to readers: do you have firsthand experience of using copyrighted texts for educational or scholarly purposes outside of the United States? What challenges or opportunities did you find relevant? If you are reading this text in its digital home, I welcome you to share your experiences in a Hypothes.is annotation layer comment anchored to this footnote. ↵

- To name just one example of a digitally mediated reading approach in practice, Susan David Bernstein and Catherine DeRose used Carnegie Mellon's DocuScope tool to compare rhetorical structures in Charles Dickens's and George Eliot's serial and volume fiction. ↵

- I say "less effort" because even the use of public domain images can be complicated. This is a consideration I will explore shortly. ↵

- In an observation that Breadsword may find poignant, legal scholar Jason Mazzone explains how copyright notices often function as a means of coercion even when companies' claims might not stand up in court: “copyright law does not punish very severely false claims of copyright. As a result, false copyright claims are common. . . . [O]verreaching occurs because content providers are able to take advantage of the fact that the boundaries between private rights and public access are not always visible to the public" (xi) ↵

- This belief in the importance of inclusive structures of knowledge circulation motivates the open access publishing movement more broadly. ↵

- This canonical text dynamic can take multiple forms. Emerging scholars may fail to see the striking originality of their work and let it wither, unseen, in a Learning Management System. On the other hand, as I am reminded often in my role as a composition instructor, emerging writers who explore 'clichéd' concepts are often generating ideas that are new to them, and this is something to be celebrated in the classroom. From the other side of the red pen, however, it can be easy to dismiss real learning as unoriginality when you are reading yet another paper on whether Viktor Frankenstein was the real monster all along. Allowing students to work with less-familiar texts can help instructors recognize the scope of students' engagement with the discipline in more critical ways—as well as more generous ones. ↵

- The "What is Open Pedagogy?" article I cite in this section emerged before recent discussions of open pedagogy led David Wiley to shift some of his terminologies. In this article, he uses "open pedagogy" to refer to activities that are "impossible without the permissions granted by open licenses"--that is, the explicit permission to remix, revise, reuse, retain, and redistribute a particular learning resource. Wiley has since re-associated this definition with the term "OER-enabled pedagogy" (OEP), registering a wider range of practices that may be seen to fall under the umbrella of "open pedagogy" ("OER-Enabled Pedagogy," DeRosa and Jhangiani). ↵

- Here again I am referring to the legal categories prevalent in the United States for reasons I mention in an earlier footnote. However, these constructions still have a wider impact for scholars outside of the US, as a robust archive of nineteenth-century media continues to be digitized and hosted by archives, universities, and others located in the United States. ↵

- Whitney Trettien has similar print-on-demand phenomenon in compelling detail in "A Deep History of Electronic Textuality: The Case of English Reprints of Jhon Milton Areopagitica." ↵

- The ruling stated that a photograph that is a "substantially exact reproduction" of a painting in the public domain would be acceptable for someone to use without paying royalties (Stokes 136 citing Bridgeman Art Library v. Corel Corp., 36 F. Supp. 2d 191 [S.D.N.Y. 1999]). ↵

- Jason Mazzone expresses particular concern about this last possibility, which he notes to be a reality in many writers' experience (Mazzone 3). ↵

A bowdlerized text is a text that has been adapted to be more 'appropriate' for audiences the author believes would benefit from this censorship. Often, elements considered to be sexual, nonnormative, or irreligious are removed from the original text.

In the United States, fair use assessments are always made on a case-by-case basis by weighing the following four factors:

1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.