A Field and Its Forms

From Cambridge Analytica to Cambridge University Press: Scholars, Student Engagement, and… Surveillance Capital?

In their 2016 update to the Framework for Information Literacy in Higher Education, the American Association of College and Research Libraries stresses that information—both for and about media consumers—has value. In the “Publications and Provocations” chapter in this project, I have explored some of the ways that institutions can extract value from academic journal articles, public domain texts, and educational editions. But to assume that avoiding partnerships with the most overtly profit-oriented publishers will address the access inequalities in our scholarly and educational systems is to ignore how data operates in the present day. No matter how openly a text is circulated and no matter how community-minded we believe our motives are for writing it, we still have a responsibility to consider how the media formats we use might detract from our goals for our work.

In this section, I consider how reading platforms can shape how individual people can gather information about readers using media publishing and circulation tools. By reflecting on hypothetical approaches to designing an interactive teaching project like The Woman in White: Grangerized, I unpack opportunities for connection but also the potential for exploitation in such work. Ultimately, I argue that literary scholars and instructors have an obligation to reflect on the new forms of power available to us—and to intermediary parties—by virtue of the platforms we write within. As critical pedagogy theorists and rhetoricians remind us, the relationship between teacher and student, writer and reader, isn’t egalitarian by default. Disrupting inequalities in our teaching and communication requires us to analyze how we deploy our writing in these contexts.

Recognizing this leads me to the following questions:

- What advantages and opportunities might arise for me as a scholar and educator by virtue of controlling my projects’ digital formats and hosting locations?

- What are the deeper ‘hidden profits’ I could exploit even if I freely circulate my texts? How might a person extract information and value from a digital dissertation or critical edition?

- Recognizing that not all commodification is bad, how can I nonetheless reduce others’ ability to profit off of my scholarly or student readers without their informed consent?

- What value trade-offs am I making by circulating my work in the open and digital formats I have chosen for this project?

- What are the broader implications of these trade-offs? How might they make me complicit in larger systems of hegemonic domination?

- How, finally, might nineteenth-century studies practitioners and other educators work together to build resistance to oppressive systems into our work?

An Apt Backstory

In many ways, the story of the nineteenth-century print boom and the increasing popularity of serial fiction is also the story of early data analytics, so my two texts’ questions about media of the past and present are once more in sync. Thanks to changing print circulation norms, Victorian authors could use reviewers’ responses in the press as well as day-to-day interactions with readers as tools for shaping their texts-in-progress. This allowed authors to increase the attention they gave to the most popular characters in future chapters and to frame themselves as being in tune with their readers. Indeed, serial culture scholar Jennifer Hayward identifies the “ability to (at least pretend to) respond to its audience while the narrative is still in the process of development” as a “defining quality of serial fiction” (23). Victorians’ own fascination with the responsiveness of contemporary print is one of the themes I highlight in the introduction to my dissertation’s critical edition, The Woman in White: Grangerized.

As someone composing texts in the present—and more significantly, as someone releasing these texts in serial installments online—I share Victorian novelists’ ability to respond to readers’ opinions as I draft and revise. The platforms I use to publish my work as well as the social media networks through which I circulate this work enable me to push beyond what would have been possible in a pre-digital era. By sharing chapters on Twitter, I can see whether a particular discussion garners attention in the form of comments, likes, or retweets. By enabling Hypothesis annotations as a default on my Pressbooks text and providing instructions on how to use the annotation tool, I can gather direct feedback about the passages that spark a response. Google analytics, Twitter analytics, and—if I ask our network administrators nicely—Pressbooks analytics information can show me other metrics for engagement: navigation clicks, external link clicks, reader country of origin, and more. As I revise, I can do so with this information in mind, modifying my text to align with the tone and topics that I believe my target audience finds most engaging.

When I realized that writing a web-based dissertation allowed me immediate insights into how others respond to my work, I thought delightedly to myself that Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins would probably approve. (Each Victorian author was especially skilled in gleaning information about how audiences felt about their serial novels in progress.)[1] Viewed in this light, one argument for writing a web-based monograph and releasing it serially on social media is that it can allow scholars insight into a readership outside of their university or social circle.

Then I thought about another favorite Victorian serialist, Mary Elizabeth Braddon, and a different dynamic piqued my interest. In this dissertation’s past life, one of my chapters had focused on Braddon’s knack for using the press to kindle controversy—and thus more buzz for her novels. Braddon had access to the world of journalism through her own editorial role and her partner John Maxwell’s publishing network. She also had a keen eye for sensational plot twists that allowed her to draw attention to herself: she and Maxwell penned anonymous letters to major publications (some even in the guise of fictional characters from other Victorian authors!) to attract more eyes. Surely, had she been a writer today, Braddon would have been at the forefront of viral advertising and data analytics. To what ends might she have turned these tools?

Because this Undissertation is interested in the changing roles of publishers, textbook providers, and product developers in shaping academic interactions around texts, my mind turned next to the profit motives that might intersect with projects like mine. Since one of my goals is to minimize my and others’ ability to commodify information about my readers without those readers’ informed consent, I realized that I needed a better understanding of digital circulation platforms.

Putting On a Market-Minded Thinking Cap

My first task in assessing the marketable elements of an open text was to take on a different persona: that of an educator-capitalist. Happily, a computer engineer in my life was willing to think deviously with me. I sat down with Mike Kellum, a full-stack software developer, to talk about how I might go about gathering as much user data as possible from my text and turning it to personal advantage.[2]

As a starting point, we imagined that I was extremely tech-savvy and wanted to develop a web platform of my own to host each component of my dissertation. In a world where I controlled both the code of my project and the avenues through which my readers were accessing it, I asked him, what could I infer about the people reading my work? If I were interested in extracting value from this text even while circulating it at no cost, what could the digital turn allow me to do that print-only texts would not?

Mike explained that browsers and apps are able to log a wide range of user engagement events such as clicks, scrolling, or points when users’ cursors travel over a particular place on the page. If I wanted to make inferences about my digital readers, I could approach their data in the aggregate or individually. For instance, he continued, if my goal was to maximize how many sections of my project people consumed in one sitting, I could track and correlate user interactions with the text to see what patterns were associated with their decisions to stop reading my work (Kellum). Put more concretely, I could say to my dissertation project: “Hey, show me where the largest number of users clicked away from the project and didn’t return.” If my dissertation told me that people tended not to make it past the introduction, I could tweak that introduction until this pattern shifted. Even better, I could use cookies to do A/B testing on my own text, assigning two different versions of a chapter to different populations at random in order to measure which version was most effective. As I learned about this ability, I imagined Charles Dickens salivating at the thought of his novels reporting back to him about his own readers’ habits.[3]

I also discovered that if I wanted to know how people were interacting with my writing on an individual level, I could do so with shocking precision. Say I wanted to know more about the people who had interacted with the text for a moderate amount of time—you, the person reading this section, for instance. Mike informed me that I could either write some code or pay for a third-party service that would create a kind of instant replay of how fast you’re scrolling through this very page, whether you click on footnotes, and more.[4] While your keyboard focus is on the page,

[the product] will extrapolate mouse movements between tracked events, so they may not be perfectly accurate, but you’ll get something very close to the actual [interaction]. It knows your screen size, the position of your mouse, where you’ve scrolled, and what you’re doing with your mouse and keyboard. That’s all there is—except eye-tracking. (Kellum)

If you were required to log in to the website or app before you were able to read this work, I could even trace your interactions with this project across multiple public and private computers, phones, and tablets. I would naturally be tempted to interpret your behavior as an indicator of your opinion, and I’d have an automated leg-up in doing so. Some products will assign emotions to patterns of behavior, such as Full Story’s “rage clicks” tracker.[5] I could use these resources to devise hypotheses about your attitudes toward my work.

Now to protect my bottom line. “In this alternate universe where I’m an entrepreneur,” I asked Mike, “do I have to worry about pesky things like letting people know that I’m tracking them like this?” Luckily, I don’t. In Mike’s words:

There is no legal requirement for disclosure. Developers typically, in my experience, see it as obvious that this information would be available to the developer. It would be like being shocked that there’s a camera in a Walmart. I can see what aisle you’re in, what items you’re touching. The difference is that I can collate that information more effectively. (Kellum)

Excellent, I thought.

Stroking my imaginary goatee like a Bond villain, I mused that I might even be able to work eye-tracking and audio recording into the mix after all. Perhaps I could make headway on this front if I presented you with a complex enough terms-of-service agreement and convinced you to enable a computer camera and microphone. Heaven knows that online exam-proctoring software already allows for this kind of tracking. My own institution, the University of Wisconsin-Madison, has a ProctorTrack integration in its Canvas Learning Management System that will use your webcam (if you have one) to record your take-home exam sessions and algorithmically flag moments where you seem to be looking off-screen.

Maybe I could note where your eyes are glazing over or when you’ve snorted aloud at some inelegant turn of phrase. . . My, that’s a nice shirt you’re wearing.

Applying Analytics

Dystopian Dissertation Data

In the era of Cambridge Analytica, the ability to use data to maximize interest in a scholarly or educational text may seem fairly prosocial. But what are the unseen benefits that an entrepreneurial academic might reap from a project like this one?

To begin to answer these questions, we can look to the things that carry the most professional currency for scholars of various stripes.

First, of course, there’s the desire to successfully make it out of a Ph.D. program and position oneself as a promising job market candidate. If my alternate-universe self were being really mercenary, I might use the data analytics my platform provided to identify my highest-profile readers. If I required a log-in, for instance, I could track my committee members’ interactions with my project across devices. I could then use the information I gleaned to pander to the advisor I felt would best advance my career if I made a good impression on them. I might also be able to triangulate information about users, reach out to my highest-profile site visitors, and network beyond my university. Frankly speaking, there is a limited audience for dissertations in Victorian studies, so if I knew that one of the most celebrated scholars of Victorian scrapbooks lived in Woonsocket, Rhode Island and saw internet traffic from Woonsocket on my scrapbooking discussion, I might take a risk and reach out to her by email. Perhaps she’d like to co-author something together—a great boon for my C.V.

Of course, any Ph.D. candidate should really be thinking several steps ahead of the game in writing their tenure-eyed text. To secure a prestigious job, I’d want to write a first book that could appeal to the flashiest academic publishers. So, let’s imagine that my A/B testing and strategic circulation of my project has been wildly successful and I’m generating quite a buzz. In order to woo Cambridge University Press, I might make it known that I’m seeing astronomical web traffic to my scholarly blog. If the bigwig scholars in my field show up in the comments, all the better for my chances of securing an elite publisher for future work.

Teaching Texts

We can assume that like the real me, Alternate-Universe Naomi is also passionate about creating critical editions that other Victorianists can use in their classrooms. But recognizing that information has value, I asked Mike Kellum how this mercenary version of me might design a critical edition that provided personal gain while still being published at no cost.

Together, we imagined that I was writing an online critical edition called Hard Times: Interactive. An obvious place to turn to for profit would be advertising revenue. As Mike and I talked, I realized that monetizing the edition in this way might change the modes of reader interaction I seek as well as the very structure of my text. Imagining that he was trying to sell my readers to third-party advertisers, Mike mused, “I’d want to maximize time on a page if there were ads in the margins, which may counterindicate things like useful links that speed up navigation” (Kellum). With pride, I realized that could do him one better. Henry James once referred to Victorian novels as “loose, baggy monsters,” but in the digital era, long texts are simply not great for selling ads. Although my critical edition in this universe splits a novel up into its original serial installments, the alternate-universe Naomi might prefer to split up Charles Dickens’s book into many more pieces so that I could fit ads in at the top of each page. Each time a student clicked back through a chapter, I could have their browser load a new commercial and pull in those advertising pennies accordingly. Since the text would be free (and potentially a compulsory edition for class), students might be willing to put up with the sidebar ads for the sake of their grades.

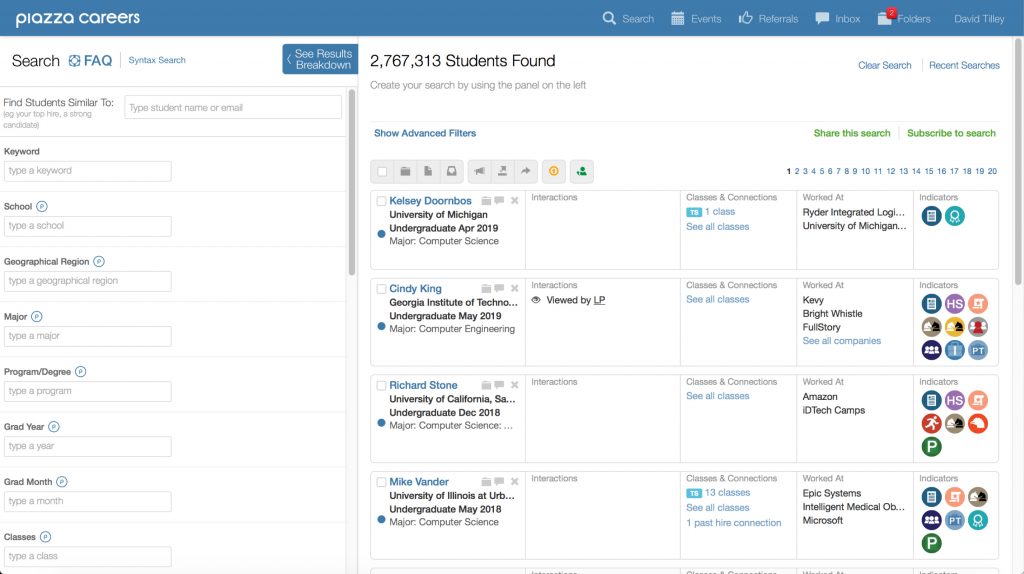

Companies want to advertise content based on users’ interests, so advertising might also give me an incentive to collect more data from students. Thinking like a textbook company once more, Mike reflected: “I’m not going to be advertising Rogaine; I’m going to be serving the students as a particular demographic to advertisers, so I’d want as much information about the students as possible—what device they’re using, et cetera” (Kellum). The idea that advertisers might find it desirable to target specific messages to students in a Victorian Studies class seemed a bit far-fetched to me at first, but I soon learned that there is already an existing market for this information: “I think Piazza gets a lot of money from industry for presenting job postings—so that’s advertising, but it’s highly specific,” Mike told me (Kellum).

Lucky for Alternate-Universe Naomi, Piazza provides a playbook for this type of multidirectional advertising.[6] As a specialized discussion platform that allows students to ask and answer questions, Piazza is a free tool that professors often embed into a learning management system such as Canvas. When a student answers a peer’s question correctly, the professor can endorse that response, granting it more weight for all of the other students in the class. This makes it an appealing resource for instructors because it saves time and allows them to commend students who help their peers. Knowing about students’ educational backgrounds and performance is valuable for third parties, so Piazza has paired up with companies to provide an opt-in job post notification service for students. Piazza can thus market students to companies as hyper-targeted advertising demographics open to companies’ recruitment emails. On its information page for the companies who advertise through the platform, Piazza exhorts employers to “use the power of our network and data to reverse engineer your star hires and find more like them” (Piazza Playbook). Its recruiting playbook provides additional detail:

With Piazza, every student you hire has a high probability of having a Piazza account. And we have rich information on our students – which classes they’ve taken, which classes they’ve TA’d, and which classes they’ve received professor endorsements in. We’re able to provide you with a list of academic traits for any of your past interns or recent grads.

Say Shelby was that star intern; just pop her name into the Find Students Similar To feature and see a list of her traits – she’s a top student in Machine Learning, a TA to an algorithms class, a college-level varsity athlete, coding since the age of 13, and a top student in at least 5 classes. Now I run a search by selecting the traits that I care most about, and within seconds, I find hundreds more like her.

I can then send a highly personalized note to a student who matches Shelby’s profile: “Hi Melissa, I noticed your profile looked a lot like one of our past star interns – she was a TA in algorithms and had been coding since a young age, not to mention involved in varsity-level sports… do you have time to hop on a call? I’d love to tell you more about what we’re doing.” (Piazza Playbook, emphasis mine)

As I delved deeper, I learned that it’s not just business, computer science, or STEM students that Piazza frames as valuable advertising targets. It would seem that academic departments’ efforts to market the humanities as business-relevant is working. Piazza even highlights an English major as a trait for employers to search for in its promotional materials.

At this point in my reflection on third-party advertising, I realized that I was stretching the bounds of what I could imagine a version of myself doing even in an alternate universe. But as I thought more, I began to see how the same tools that ed-tech companies market to advertisers would translate into the strange value systems that emerge in competitive academia.

Say I am an ambitious professor with a penchant for coding, a fully-functional critical edition of Hard Times: Interactive, and a class of 400 undergraduate students. I’m kind of a big deal,[7] and so a portion of my class is desperately hoping to work with me on their honors thesis so they can get a name-brand letter of recommendation to include in their grad school applications. Obviously, I have limited time to spend working with undergrads, so I’ll only want to work with the people I consider to be the best and the brightest.[8] To determine who these students are, I might log into the admin panel of my critical edition authoring platform. I would next ask the platform to display the students who have spent the most time actively reading Hard Times: Interactive and have taken the most private and public notes in the text. Assuming these qualities to be proxies for real commitment to our craft, the top five students on this list would receive primary consideration for honors thesis advisee. Alas, the students who can’t afford internet access at home might screen-shot the text for later reading offline. This would mean that my dashboard’s time estimates for them would show no engagement whatsoever, so I’d be less likely to accept those students as advisees because of my mistaken assumption that they were work-shirkers. But no matter—there are always more students than opportunities anyway.

As that same kind of ambitious professor, the stakes are higher for me when I consider grad students to work with. In an economy of scarcity where I only have so much time to devote to mentorship, the choice of grad student advisees matters all the more. Ideally, all of my handpicked graduate students will move on to become the next Judith Butler, and perhaps algorithms will help. (Ah, the joy it will be to sit down to dinner with other scholars and nonchalantly tell them about the sweetest letter I’ve received from my old protégé, Jacques Derrida Jr!) So perhaps I’ll code my own version of Piazza’s “Find Students Similar To” function into Hard Times: Interactive. I’ll track prospective graduate students’ interactions with the text. Those whose patterns of highlighting and annotation most closely resemble and innovatively depart from those of my most successful advisees might have what it takes to make it in the big leagues.

Because I don’t yet know what kinds of data will be the most relevant to my future work, it will behoove me to gather as much information from my readers as is feasible given my university’s level of oversight and my project’s storage constraints. Perhaps some unknown patterns of behavior will emerge as striking correlates for professional school success! Perhaps there will be unforeseen ways for me to monetize this data years from now! Either way, it can’t hurt to engage in a little bit of data-speculation. Like a mining company purchasing land rights, I’ll leave plenty of wiggle-room to hedge my bets on the data I collect.

Don’t worry: I’ll include an opt-in function. Students will have a choice to have their data collected analyzed in this way. But considering that the new science of close-reading analytics is all the rage right now and that people in the humanities are reputed to be the good guys, most students will probably say yes.

True, there may be some students with more reason to fear surveillance culture than others. Perhaps they’ve been the subject of one too many racial-profiling-inspired airport searches and would prefer not to accept my tracking cookie. That’s just fine: they’ll simply not be included in the analysis; no harm, no foul.[9] This would be unfortunate for those who opt out and might lead to a more homogenous pool of advisee contenders for me. “But then again,” a person who used information in this way might say, “it’s not like I would be deliberately discriminating against anyone. It’s just an unfortunate proxy variable for lack of privilege and proximity to state violence.”[10]

Brain-Reading: Reader Analytics and Educational Neurotechnology

Once Alternate-Universe Naomi has handpicked the cadre of undergrads and PhD advisees who will carry forth my legacy, I can expand further. Perhaps these students and I will work together on some exciting grant-funded projects at the cutting edge of pedagogy and the postdigital humanities.

Say my whole team is fascinated by research on the differences between expert and novice ways of thinking within disciplines. Maybe we’ll want to gather data on how different readers’ minds and bodies react during an encounter with a Victorian text. Our reasoning is that there may be analyzable patterns of difference among undergraduate students, graduate students, and elite scholars as well as among folks within different subdisciplines in literary studies. Brain and body sensors are becoming more widely available in many forms, so if we can gain funding, we have a good shot at acquiring some tools to help us.

We apply for a prestigious grant. In our application, we hint that the data we obtain could help us to speed up the process of educating undergraduates as well as future faculty. We’ll stress the words ‘efficiency,’ ‘machine learning,’ and ‘artificial intelligence.’ It will all sound very impressive, and when they read our dossier, the grant committee will fantasize about reducing time-to-degree numbers and streamlining faculty development using these tools.

Lucky for us, people in high places in the United States education system already have brainwave analysis technologies on their radars, and we have a hunch that this will help our funding case. My hypothetical team will delve deep into research on educational neurotechnology. We’ll be delighted to find Ben Williamson’s 2019 article, “Brain Data: Scanning, Scraping and Sculpting the Plastic Learning Brain Through Neurotechnology,” and read the following lines: “Head of the US Department of Education, the private-education advocate Betsy DeVos, is a major investor and former board member of Neurocore, a brain-training treatment company specializing in neurofeedback technology development and application” (78). Our hunch proves correct. The day we receive our grant, our team will celebrate with a cake shaped like a brain.

Next to assemble our tools. All of our project participants will spend two hours a day reading the Hard Times: Interactive edition I’ve created.[11] To measure whether our subjects’ hearts beat faster during parts of the novel, we’ll have them wear electrocardiogram (ECG) electrodes whenever they interact with the web edition. Using insights gleaned from research on affect recognition technology, we hope to use the electrocardiogram to identify moments of emotional arousal that occur while people are focused on the text.[12]

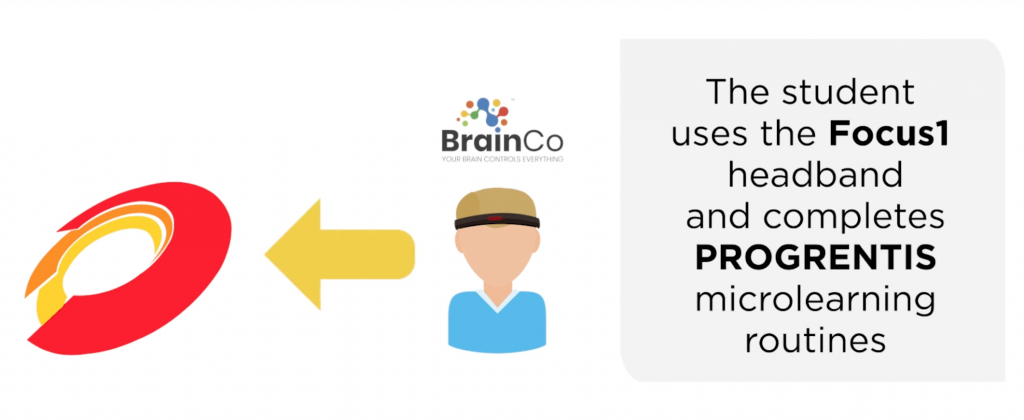

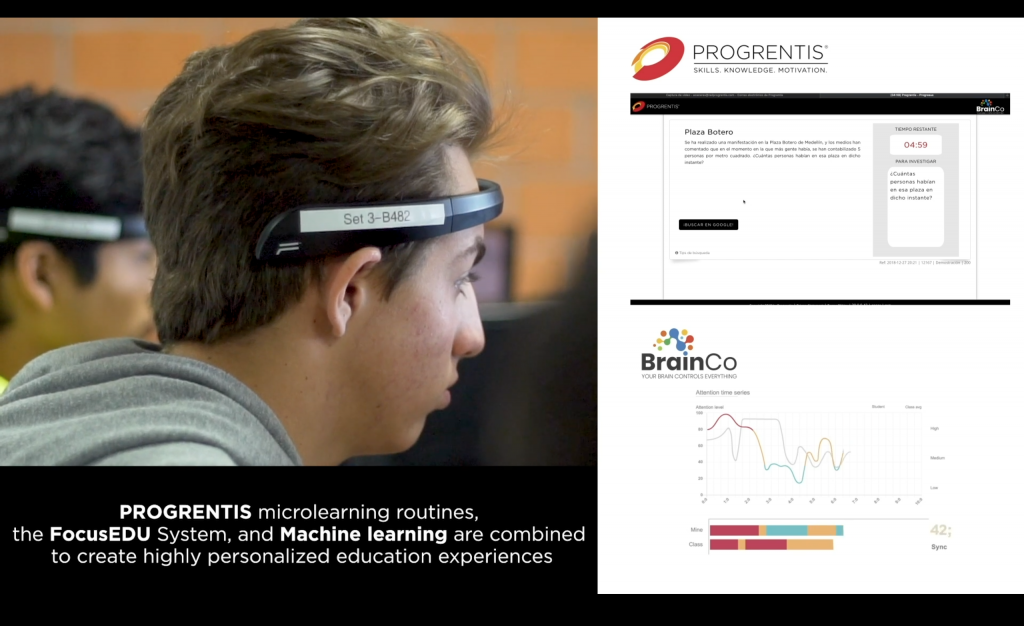

To record participants’ measurable brainwaves, we will tap a company already working on educational neurotechnology devices. Originally devised at Harvard, BrainCo’s Focus EDU tool combines an electroencephalogram (EEG) headband with data analytics displays for instructors as well as students:

With the help of software developers, our team will combine the biological information we get from the EEG and the ECG, the eye-tracking data we get from students’ webcams, and the screen interaction data we track from students’ browsers as they scroll through Hard Times: Interactive.

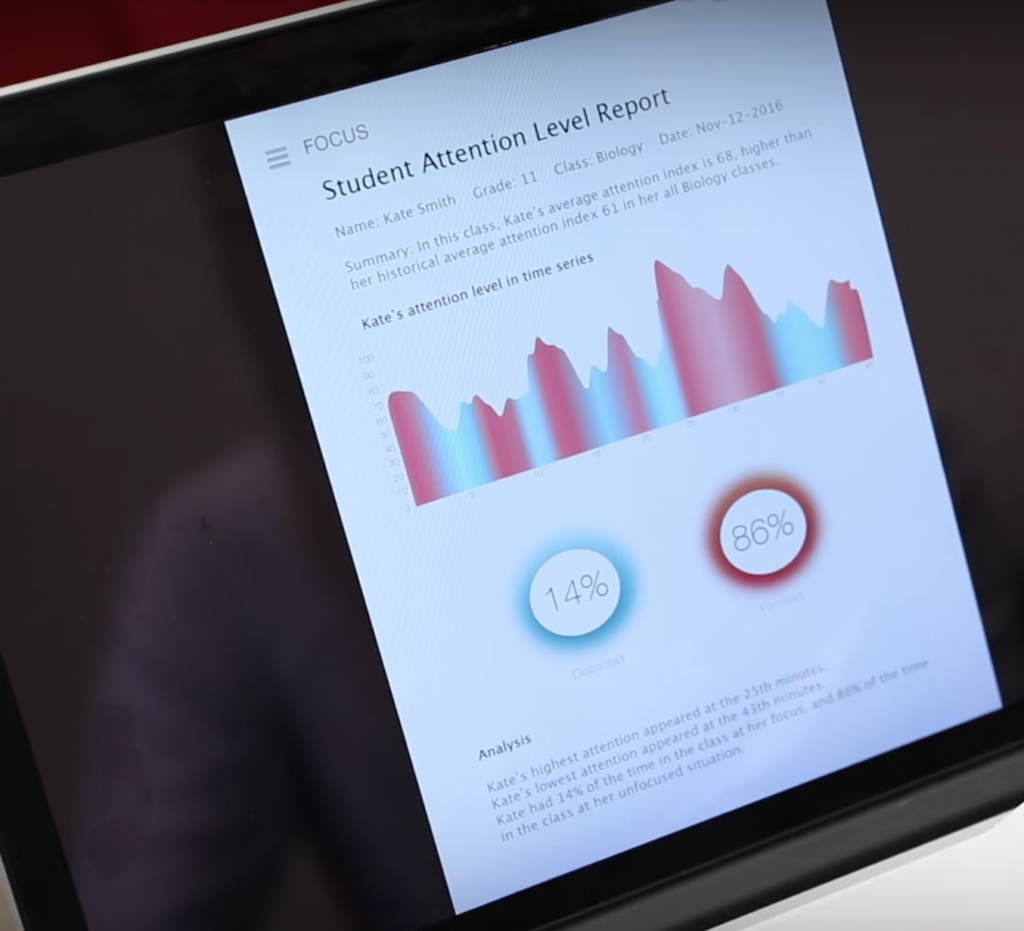

Looking at such data in combination could play a huge role in how we adapt Hard Times: Interactive and how we teach it in classes. Successful learning requires student attention, and FocusEDU emphasizes its ability to quantify student attention and display it to instructors and students in actionable ways. BrainCo alleges that instructors are able to compare students’ levels of attention in the aggregate and individually using a real-time course dashboard. Presumably, we could use the data we collect over time to create a record of students’ responses chapter-by-chapter, page by page, and sentence by sentence. If a majority of our readers seem to be losing focus at a point in the novel that we feel is important for them to pay attention to, we can devise supplemental interactive activities to include at that point in the text.

We might use this data to help individual students develop college-level reading and notetaking skills! This could involve presenting them with attention-feedback reports each time they finish a chapter of our text. BrainCo already advertises similar reports about EEG-recorded attention during class periods, so customizing this kind of feedback report for our purposes could be fairly simple.

Once we’ve gathered and analyzed data about successful students’ emotional reactivity and attention levels while interacting with different points in our text, we can start to work on a ‘nudging’ system in our version of Hard Times: Interactive.

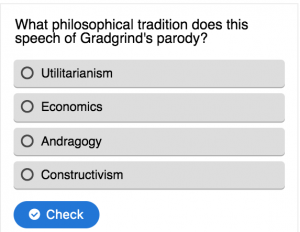

Put in concrete terms: imagine that our critical edition’s records suggest that a large percentage of successful students read the descriptions of Thomas Gradgrind’s schoolroom in Hard Times with great attention, but students who received lower grades in class were more likely to skim through these sections or navigate away from the page. If I’m a reader whose focus pattern begins to deviate from those of my most successful peers, Hard Times: Interactive might ‘nudge’ me toward more desirable behavior by popping up a required short-answer reflection question, video, or quiz to call my attention back to the text.

A Nudge

“Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else. You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them. This is the principle on which I bring up my own children, and this is the principle on which I bring up these children. Stick to Facts, sir!’” – Thomas Gradgrind, Hard Times Ch. 1.

One stumbling block:

Our team recognizes that there are many things we may fail to consider, misinterpret, or devalue if we uncritically rely on our assumptions about the data we gather from our readers:

- Maybe one of my students appears to have lost focus on our text, but only because a description in the novel has so sparked her interest that she’s taking a break to research the Victorian education system rather than interacting with Hard Times narrative in a continuous way.

- Perhaps knowing that their reading process is being digitally analyzed exacerbates stereotype threat for some students from minoritized groups. This may affect these students’ emotional responses and degrees of focus, thus reducing their self-efficacy and disrupting the accuracy of the program’s analysis to boot.

- Perhaps a student who has a visual impairment is using a screen-reader to interact with the text. Our program might flag her as an outlier because of the way that screen-readers are able to navigate nonlinearly through the text, jumping from heading to heading or hyperlink to hyperlink. If I’ve been inspired by the Piazza model and have decided to give potential employers access to student interaction data, this student may not show up in a recruiting search for candidates who have strong humanities profiles simply because her modes of reading don’t easily align with other successful students’.

- Perhaps a student who is an English language learner appears to be scattered in his approach to the text because he is translating words in Dickens’s prose that are no longer common in American English. He may be just as reflective in his approach to the text as other students, but he is also learning an additional layer of information through this reading experience. Unfortunately, the added benefit of this experience may be difficult for my algorithms to quantify. The time this student takes to write down the new words he has learned may tell against him on my dashboard.

- Perhaps the interaction patterns correlated with the highest number of successful students in the class fail to account for neurodiverse approaches to reading that nonetheless lead students to a clear understanding of the text.

- Perhaps a student in the class intermittently stops reading or goes into a reverie because he’s spotted a scene in the text that would lend itself well to a creative retelling on Archive of Our Own, a fanfiction archive where he has a large following of his own readers. [13] If they were his instructors, scholars such as Kavita Mudan Finn and Jessica McCall would celebrate the ways that writing fanfiction can involve many forms of critical analysis that conventional literary studies assignments also strive to teach. Yet to the algorithm, this student would appear to be unfocused.

In each of these cases, a student’s modes of reading Hard Times: Interactive may differ from what I or my algorithms interpret to be indicators of successful engagement. In each case, these students are held up against a normative concept of reading that doesn’t allow for multiple approaches to learning, styles of engagement, or students’ other learning needs. If our nudging system relies on the small subset of learning behaviors it can measure, some of its interventions could be unhelpful or even detrimental for students.

Because we’re scholars of reading and literacy, my team and I will be sensitive to these limitations. As we gear up for our next round of grant applications, concerns about one-size-fits-all algorithms will prick at us. A composition and rhetoric graduate student in my department will suggest that this time around, we apply for funding not for platform development or more electrode headsets, but for a large-scale qualitative research project. To understand the unexpected ways participants learn as they read Hard Times: Interactive, she will insist, we need to interview a diverse pool of students. We even have a leg up in identifying interview candidates—our dataset already flags interaction patterns that appear idiosyncratic! Why not ask these apparent outliers if they’d be willing to talk more? Why not speak with students who use screen readers or other accessibility devices and ask them how new options in our interactive text could better support their modes of reading? Why not listen to readers as they describe discussions with their peers in the annotation layer that helped them feel supported and enthusiastic as they moved through the novel? What else would we learn if we designed an open-ended interview process, coded these interviews, and looked for patterns that could change our authorship and teaching practices?

As a scholar, I’ll be faced with a quandary. I want to continue to create cutting-edge, interactive critical editions of nineteenth-century novels and share them at no cost to students and colleagues. To make this feasible, I will need funding for technology and for graduate student stipends as well as support from my university administration. Unfortunately, in my experience, cold, hard numbers tend to be far more appealing to grant committees than qualitative data. I strongly suspect that if we propose the interview project idea to the big grant committees, I’ll be less likely to receive funding. Likewise, my attention will be divided between the interview initiative and keeping up with the cutting edge of learner data analytics. My team and my project will suffer for it. If we apply for support to purchase the latest ed-neurotech and student engagement tools instead, I may even be able to start a new data-sensitive critical edition this year and support yet more students at universities the world over. I see this as an opportunity to triage a system in which many students are not otherwise able to afford high-quality editions in my field.

My university also has a stake in the direction my team decides to pursue. Just as the BrainCo headband was a project that began at Harvard and extended into industry, so too could the code my team develops move outside of my Nineteenth-Century Studies silo. As of 2019, textbook companies have moved away from the book-selling business and embraced the business of selling interactive reading platforms in their place.[14] My project is on these companies’ radars. We have plenty to offer: my team’s background in pedagogy, literary studies, and the history of reading has led us to make creative advances with our interactive editions, and the data suggest that students are thriving. My university would love to strike a lucrative deal that would allow textbook companies to incorporate some of my reading platform’s student engagement processes into their own products. Continuing to pursue the digital learning analytics and advertising angle will ultimately be more profitable for my school.

With one part regret and two parts jaded pragmatism, I’ll explain my triage mentality to the graduate student who proposed the idea. As a new research direction for my team, a large qualitative interview project is simply not realistic. Perhaps she can do some of these interviews at a much smaller scale as part of her dissertation project, albeit without funding support. Her project could make a difference, I’ll tell her, especially in a world where we’re learning so much more about supporting diverse students’ needs rather than privileging a small subset of undergraduates. I’ll even chair her dissertation committee if she decides to do so. I’ll dearly hope that she agrees.

Data-Mining and Platform Takeaways

Integration Obligations in Our Classrooms

Lest this is lost on anyone: I’m not advocating for the hypothetical scenarios I’ve just described. These narratives are flippant, grim, and pragmatic in turns, but they don’t represent inevitabilities. In the universe that you and I share, I’m deeply concerned about the ways that emerging reading platforms could distribute the most benefit to the most privileged and the most risk to the most minoritized. I see it as a core responsibility of scholars and instructors to pay attention to the unintended consequences of these tools. It’s also our duty to ask educated questions when others express concerns about them. I believe that we can help bring about important course-corrections if we make these discussions more central to our work.

But I’m also torn. While I don’t recognize the alternate-universe-me that I’ve described here as being particularly similar to the version of me writing this essay—(not least because I am not burdened with tenure advancement pressures)—there are still some aspects of these scenarios that touch on questions I hold dear. On the one hand, I feel a wave of discomfort when I imagine looking at a chart of my students’ eye-tracking data or standing in front of a class filled with students wearing EEG headbands. But on the other hand, I’m someone who genuinely loves experimenting with creative reading and teaching technologies. When I imagine getting to see what my own EEG feedback looks like as I read a chapter of The Woman in White or a critical article, I’m fascinated. When I imagine being in a room with others who feel the same fascination about new reading technologies (but whose data is somehow safely protected from appropriation), I’m intrigued. Where would our discussions take us, I wonder? What would we learn about our own unexamined assumptions about data correlation versus causation or about others’ experiences of reading that we might not have uncovered otherwise?

I think that this cognitive dissonance is familiar to many of my teaching colleagues. I’d like to lean into it together.

Here’s just one reason why: we don’t actually have a choice. What strikes me the most when I consider the first two scenarios, at least, is just how realistic they seem when I consider the tools that are already available to me within my current institution. Elsewhere in this project, I argue that it’s important to create educational resources that are interoperable.[15] But to make a text that can be easily read by or imported into another program is to lose (the semblance of) control over others’ uses of that text.

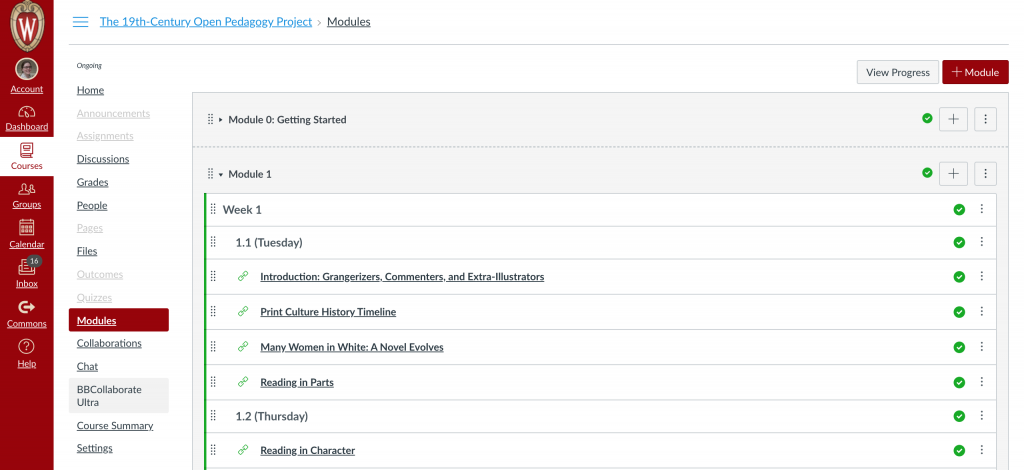

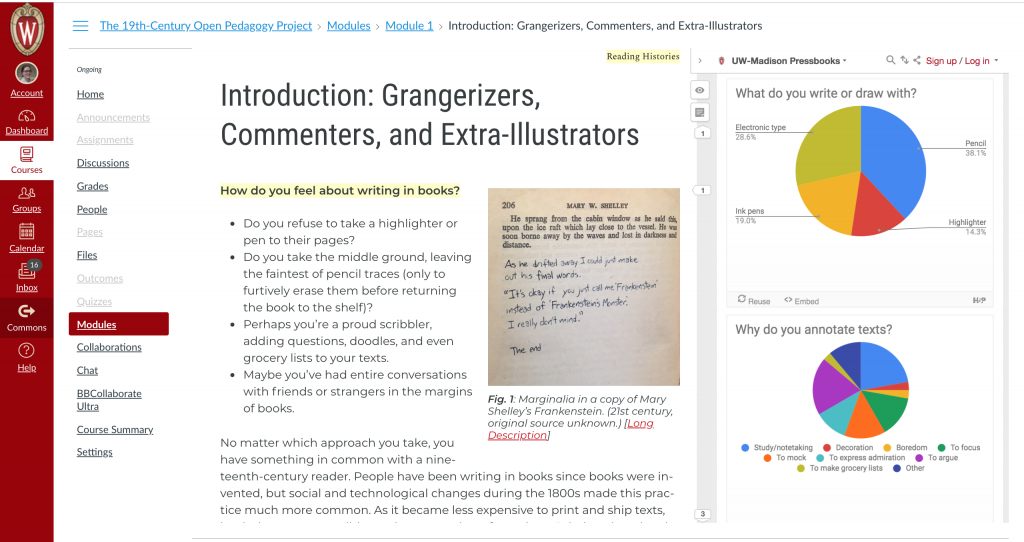

As it stands, I’ve chosen to use Pressbooks as a platform for hosting my project. I appreciate that the company presently includes people who are passionate about open publishing and student data privacy.[16] I also appreciate that the platform’s developers care about ease of incorporating texts into existing teaching workflows: another student-centered impulse. Thanks to a Pressbooks integration, my critical edition, The Woman in White: Grangerized, can be easily imported into my Learning Management System (LMS) to better align with many educational contexts. This, in turn, reduces students’ and instructors’ barriers to entry for this text. [17]

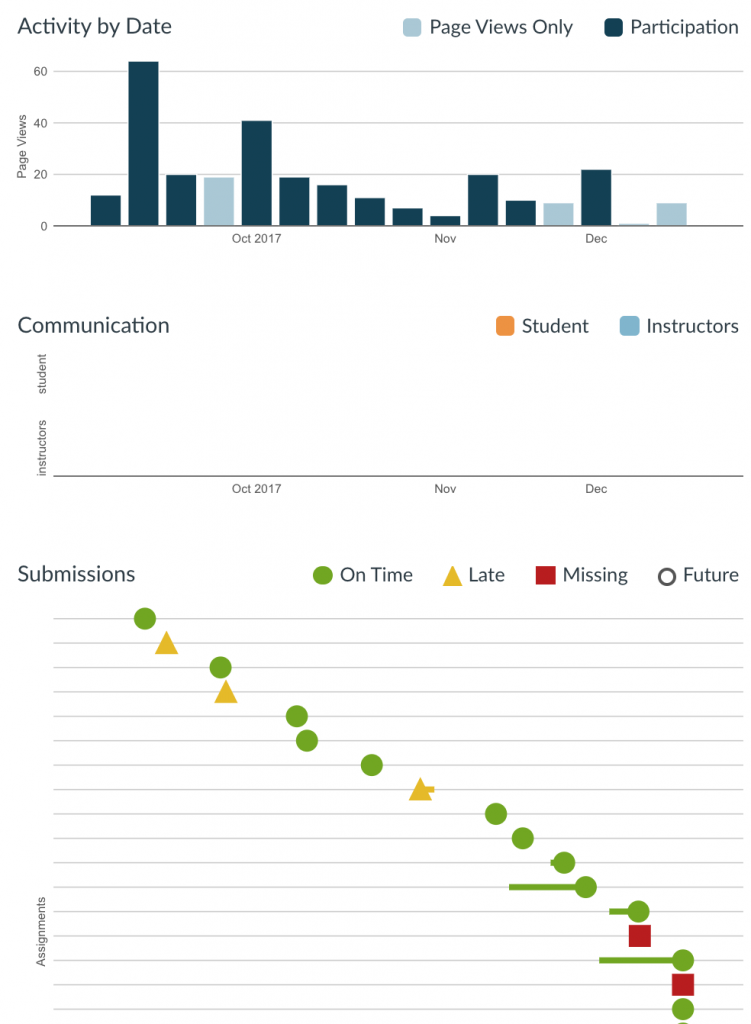

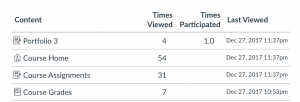

Interoperability is an advantage, and yet the moment I imported the text of my critical edition into a Canvas course, I also gained the ability to track the amount of time that individual, named students spent on our course’s Canvas site and on each separate course page. Here’s what that looks like in practice as of 2019:

Here, the interoperability of my platform has plugged my project into a tool that can be used to start conversations with students about how they’re doing in our course (a good thing), but also to compare students with one another using potentially-misleading information (a bad thing). Framed in concrete terms: the charts in the screenshot above may approximate how engaged a student was with our course content, but it’s risky to assume that this is always the case. Although it appears that my student dropped off the map for a short while in early November and early December, for all I know, he was spending every waking moment committing passages from our course texts to memory or composing a brilliant peer review response for another student in our class. Nothing about this data compels me to conclude that this student was disengaged from my course during these periods of time, but nothing about this dashboard leads me to reflect on other ways he might have been engaging with the course either.

This isn’t a reason to rid ourselves of this dashboard, but it is a reason to consider how we might proactively offset the assumptions we may make about student engagement across all of the platforms we use to teach. Knowing that a reader interaction dashboard offers us a very limited insight into students’ experiences should sharpen our attention to company rhetoric that implies otherwise. This knowledge also increases our responsibility to find other means of asking students about their experiences and making course resources available to them on their terms.

Let’s anchor this once more in the example of a digital critical edition. Say I’m an instructor who is excited at the thought that the teaching text associated with this dissertation, The Woman In White: Grangerized, is available at no cost to students and includes a number of interactive elements. This project’s openness and interoperability mean that I can incorporate it into my course in a range of ways.

One route is to follow in the footsteps of the textbook companies who are moving away from a text production model for educational materials and toward a software distribution model.[18] In this ‘vertical integration’ approach, I’ll use the digital tools at my disposal to maximize my control over the book. To mine data as effectively as possible, I’ll want my students to read the text only in its digital format and only within our learning management system. Unfortunately, the fact that the edition is an OER text means that my students can access it for free on the open web and also download it as a Kindle, iBooks, or PDF file, so students who don’t like reading on their computers or don’t have steady internet access may find ways to read that I can’t track. But because this text is an open resource, I also have the ability to make a cloned version of that text and then click a button marked “Restrict content to LTI Launches.” The contents of my cloned text will only be accessible if my students access them through the embedded text in my learning management system. Using in-class statements and some strategic design decisions, I can try to compel my students to access the text through channels I maintain. This will allow me to compare their interactions with one another more comprehensively.

A better route, I believe, is for me to engage my students in a discussion about how they read for class. I can make sure that they not only have access to but also know how to use different formats of the text and different note-taking affordances within the text. To the extent that I have incorporated interactive elements into the text—quizzes, required discussions, and audiovisual content—I can describe ways to start with one preferred form of reading and return to the embedded version of the text that lives in our classroom platform. This latter approach offers learning benefits for students. Providing access to media in multiple forms accommodates students’ diverse abilities and life circumstances. Offering both PDF and print exports, for instance, improves screen-reader accessibility and accommodates handwritten as well as digital notetaking. This is in line with best practices for Universal Design for Learning, which can be distilled as providing students with multiple means of engagement, representation, action, and expression.[19] In a similar vein, when instructors have conversations with students about how they might diversify their reading strategies in different contexts, they call students’ attention to student’s own learning processes and give students the opportunity to refine them.

Easy peasy, yes? To address some of the power imbalances infused into our teaching platforms, we can be clearer and more deliberate in the way we describe texts’ affordances. We can create viable options for people to engage with writing and teaching materials in a variety of ways. Built into this process are useful checks on some of the ways that my use of a digital platform could lead me to make assumptions that compromise my goals for student learning.

Higher Stakes

But of course, it’s not so simple, and this is why we need to marshal the efforts and voices of the scholarly community as a whole.

As I narrated the scenarios above, I briefly described some of the unintended consequences that might arise from the way my alter-ego was implementing digital platforms. If I had access to information about individual readers’ interactions with my dissertation, I might be tempted to tailor my writing to appeal to the people with the most gatekeeping authority in my field. If I used a free discussion platform that lets students opt in to have their data sold to third parties, decontextualized data that was scraped from my students’ interactions with my edition could help or hurt them on the job market. If students had the chance to benefit in class by releasing their interaction data to me, those students who had legitimate reasons to be uncomfortable with such tracking might be pushed behind the curve in small but significant ways.

If we look once more into the potential effects of these acts, we can see some of the mechanisms through which power is consolidated along lines of privilege in the academy. Being more transparent and providing different media formats for students to engage with is a necessary step, but this alone isn’t going to address some of the deeper concerns we need to grapple with.

One last time, let’s delve deeper into a hypothetical path forward in my discipline. This time, however, we’ll incorporate only tools that people like me can already access without grant funding. We’ll consider what these tools can accomplish and how they can exacerbate oppressive, exclusionary dynamics in my field.

Imagined Audiences

We’ll start by considering what it is that my not-so-secret urge to track my dissertation readers’ responses reveals about my institutional context. Obviously, the idea of designing digital tools that would allow me to analyze individual dissertation committee members’ feelings about my work is a little extreme. However, the factors that motivate this desire to analyze these readers’ interactions are real. My committee members’ opinions already carry far more weight than other readers’ opinions do because of the nature of a dissertation advising relationship. I already write with them in mind as a primary audience, and I do so for many good reasons. For one thing, my committee is made up of excellent scholars who are well-versed in my area of study. For another, they determine whether I move forward in my field.

Conveniently, I already have ways to tailor my writing for these readers without the intervention of technology. When we meet in person, my advisors provide me with their critiques and preferences. Most of the time, I incorporate their suggestions because these suggestions are genuinely useful. However, I’ll admit that sometimes, I will incorporate suggestions that don’t seem like an ideal fit for what I am trying to accomplish. I value my advisors’ perspectives, and if sometimes it feels like these perspectives carry more weight than my own, that is because within the institutions I inhabit, they often do. On an individual level, the guidance of established faculty in my field helps me progress from being a novice in the discipline to being well-versed in the conversations and writing conventions that my field most values.

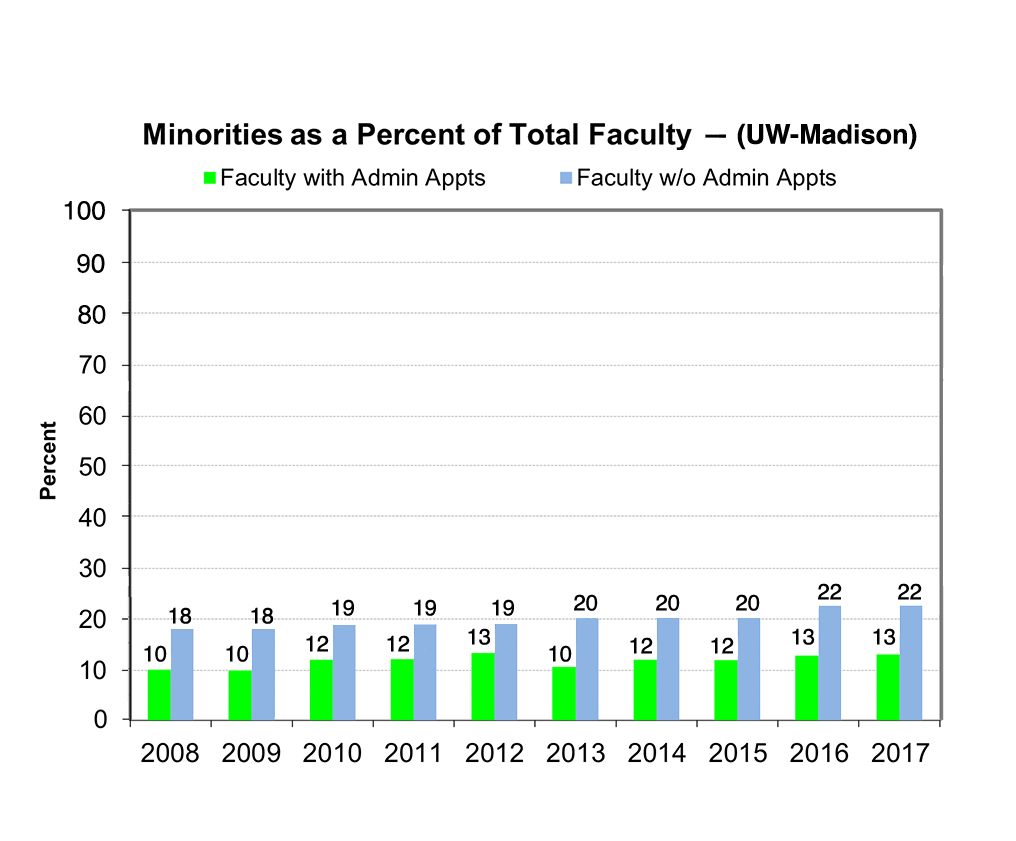

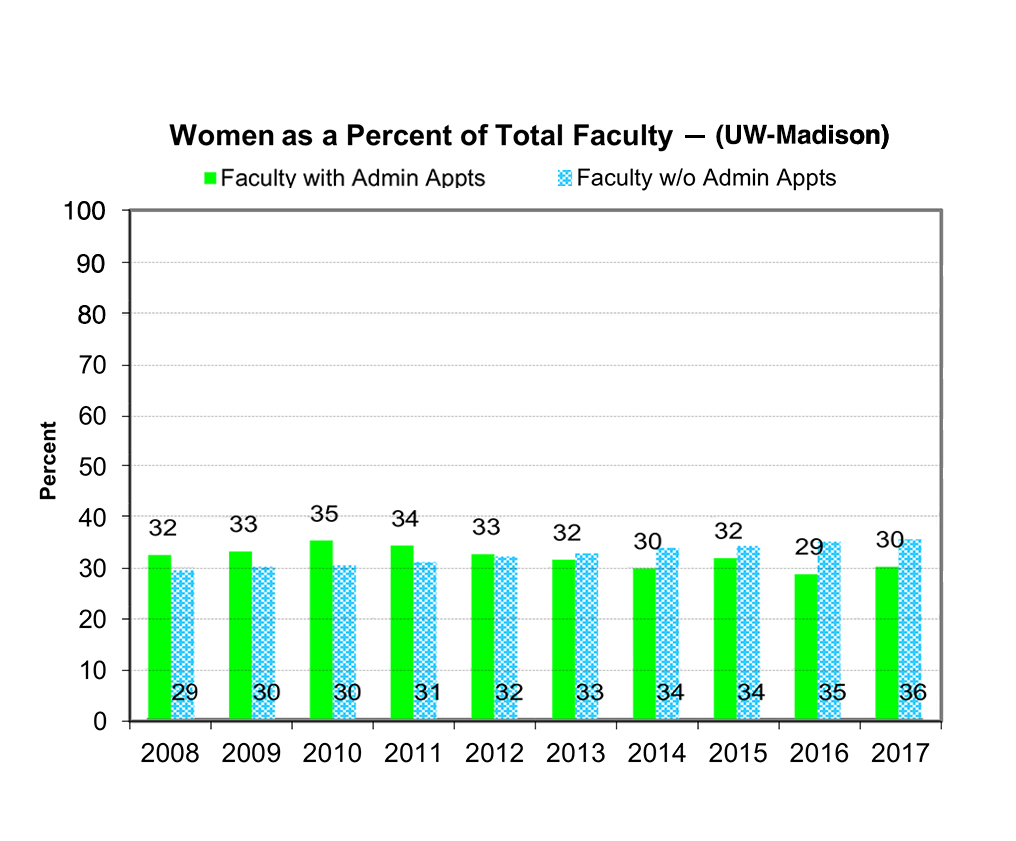

However, when we consider the ways that addressing a localized imagined audience like this one is likely to shape my approach to scholarship going forward, we can recognize a troubling limitation. Over the course of several years, I’ll spend a significant amount of my time viewing my work through the eyes of colleagues who—taken as a collective group—do not resemble my future students or the range of people in my hoped-for reading audience. The demographics of faculty at my institution hardly reflect the demographics of the country in which I work. For one thing, as of 2018, white faculty members significantly outnumbered people who identify as being Black/African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian, or Hispanic. Of 2,140 total faculty, 1,667 people—that is, 78%—identified as white only or didn’t identify their race or ethnicity (“Data on Women and Minority Faculty and Staff 2009-2018“). In contrast, in that same year, the United States Census Bureau estimated that 60% of Americans are white alone (not counting people who identified as Hispanic or Latinx). 50.8% of people in the 2018 US census were identified as female compared to 35.8% of people identified as women in our faculty demographic data at UW (United States Census Bureau, “Data on Women and Minority Faculty and Staff 2009-2018.).

To share a longer-term view of employment demographics, I’ve drawn these charts from the September 2018 edition of the “Data on Women and Minority Faculty and Staff at UW-Madison” report, which is compiled for the Committee on Women in the University each year. I have edited these charts to better reflect the fact that each bar represents a percentage out of 100. The original document truncates the y-axis on each of these charts. (In the original document, the top percentage listed on the y-axis of the “Minorities as a Percentage of Total Faculty” chart is 25%. The highest for the “Women as a Percentage of Total Faculty'” chart is 70%.) Source: “Data on Women and Minority Faculty and Staff – 2008-2017.”

Let’s pause to acknowledge that yes, there are problems with using these national and local data without contextualizing them in more detail. Yes, we need to approach any comparisons with nuance. And yes, the faculty demographic information I have is an aggregate of people from departments across the university, so it doesn’t account for the makeup of my specific English department.

But it’s significant that there is a lack of representation of this scope within my institution and beyond it: research on faculty employment suggests that broader structural factors in the US academy limit access to faculty positions for underrepresented minority scholars. These factors also create a harmful working environment for many of the minoritized scholars who accept a faculty position. To explain the scope of some of these larger trends, medical sociologist Ruth Enid Zambrana points out that “social status identity inequality (race, gender, ethnicity, and class background) influences mentoring, discrimination, work-family balance, and coping strategies and in combination potentially adversely impacts physical and mental wellbeing” (Zambrana). This lack of representation and the institutions that support it influences how my field constructs its scholar-subjects.

In broader strokes, the fact that employment demographics at other educational institutions reflect these same structural inequalities suggests that a significant number of my fellow literary studies scholars have also cut their teeth on dissertation projects that disproportionately address an imagined white audience. There are echo chambers here, and the traditional, closed-door PhD dissertation format does little to disrupt them. This is a problem because it shapes the way the field’s conversations evolve and is a marginalizing force besides. As a PhD student, I’m expected to share my work at conferences and in journal publications in order to get my name out there and to be exposed to other academics’ opinions about my work. But if I’m only writing for paywalled journals, my primary audience is embedded in privileged institutions. If I’m piloting my work at conferences, it will be to people who can afford to travel, who can afford to take off work to attend those conferences, and who feel like they belong in those academic spaces enough to get something out of their interactions.

So, within and outside of my institution, my writing context leads me to prioritize an audience that disproportionately enjoys dominant-group privileges of various sorts. Zeus Leonardo connects this process to broader patterns of exclusion and resistance to necessary change, explaining that “when scholars and educators address an imagined white audience, they cater their analysis to a worldview that refuses certain truths about race relations. As a result, racial understanding proceeds at the snail’s pace of the white imaginary” (Leonardo 141). Without sufficient discussion of these dominant echo chambers and without analog and digital structures designed to resist them, I will continue to uncritically replicate white supremacist perspectives in my writing and my teaching.

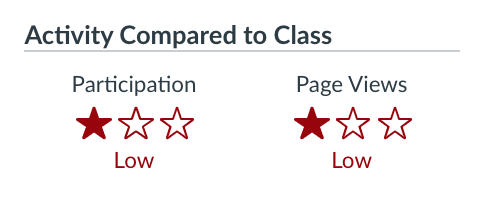

Student Engagement

We don’t have to stop there! Next, we’ll consider my (semi-)hypothetical early experiences in the classroom. I genuinely love teaching, and I just as genuinely need to make ends meet over the seven-plus years I spend in graduate school. So I spend six of those years working as a graduate student instructor. For a few of these semesters I am a teaching assistant, but most years, I work as an instructor of record in introductory composition courses. I design my own syllabi, set up my own Canvas pages, and determine what students read and how they access course materials. When I click on each student’s name in Canvas, I’m automatically presented with a three-star rating visualization that compares their page views and ‘participation’ levels to their peers. I can’t help but roll my eyes when I look to see which student has spent the least amount of time on our course page. Of course it’s that guy who always falls asleep in class. Only later do I learn that unlike the other students in his section, he works a night shift. (I’ll also learn that falling asleep in class can be one of the warning signs of food insecurity. No one will have taught me that in my TA training sessions before. Likewise, no one will have invited me to think critically about the course data dashboard I’m presented with each semester.) For years, the automated three-star student rating system doesn’t make me bat an eye.

When I write my first book, it is peppered with references to secondary scholarship that the majority of the population cannot access without significant difficulty. I’m able to write my book in the first place thanks to the existence of paywalled primary source archives. Despite the fact that these sources are in the public domain, corporate interests have artificially locked-down reuse permissions for the periodicals I study, but I’m lucky enough to have the institutional, financial, and social capital to reprint these primary sources in my scholarly work. Over the course of my career, as libraries deaccession fragile texts and corporations swoop in to cache them, my ability to navigate increasingly labyrinthine click-wrap and browse-wrap terms-of-service agreements becomes an essential part of my scholarship. This, coupled with an institutional travel budget that allows me to take unrestricted photos of public domain texts, increases the gap between how I’m able to engage with primary sources and how the ‘general public’ is able to do so. Scholars and students without these rarified resources? Not so much.

Troubled by the access disparities woven throughout my field as well as by the need for a student food pantry on my campus, I take the time to compose a freely-accessible critical edition of a Victorian novel: I want to make it easier for students to afford to take my class. This volume, too, is peppered with references to paywalled resources, but because I teach at an R1 university and my students can access these texts, I’m not concerned. Students at other institutions who want to use or adapt this text may not have this access, but that’s something I can’t really help.

Once it’s finally complete, I’m delighted to be able to integrate my interoperable, interactive text into my Canvas course. Although I do use a third-party resource such as Piazza as a student discussion platform, I do everything right. I discuss privacy considerations with students in a transparent and caring way. I let them know that they have the opportunity to opt-in to be included in recruitment searches through the platform, but they’re under no obligation to do so. I tell them that they can come to my office hours to talk about job-search resources and application strategies outside of this platform.

I’ve worked hard to ensure that the edition students are using is carefully constructed. Having forged connections with other nineteenth-century researchers at conferences, I’ve been able to include short essays about the novel written by some of the most influential scholars in my field.[20] But there are significant gaps in the stories that researchers in my field focus on the most. Although I’ve tried to appeal to student imaginations by inviting them to read my text with an eye to the range of ways that nineteenth-century readers interacted with fiction, I’ve failed to connect with many of my students. It is the readers who enjoy the most privilege who are best able to see themselves and their families’ history represented in the supplemental essays in the text. In contrast, a genderqueer student in my class won’t see that part of hir experience represented in these contextual overviews, each of which draws on primary and secondary sources that represent gender in binary terms. (This despite the fact that such perspectives on gender weren’t universal during this period.) A student of color won’t learn much about what his day-to-day interactions could have looked like in Victorian Britain: these details are missing in my text as well as in my in-class lectures.[21] These students have excellent imaginations, but the activity seems inauthentic—yet another moment where to participate, they need to look through the eyes of white, straight, cisgender people.

Unfortunately, because I’ve made much of the fact that our class’s critical edition is filled with essays from the most elite writers in the field, I’ve unwittingly reinforced the idea that these are the voices that have the most value in our classroom. My students recognize that they don’t have a PhD, a professorship, or a book deal with Cambridge University Press. Maybe they’re not English majors to begin with. If they wanted to help correct the record, who would even listen? These students can write an essay for class, but they know that I will skim it once to leave comments on it and then it will wither and die in their learning management system. Why put forth the effort—especially when that effort will be higher for them because secondary sources will resist their attempts to find nondominant perspectives at every turn?

So What?

Each one of these more realistic narratives reflects a process that causes privileged people to be overrepresented in the field. We can borrow language from Zeus Leonardo to put this in a different, more pointed way: these are what we might call the “material preconditions that make possible a social condition” in which people who inhabit dominant identities gain resources to the direct, material detriment of minoritized people (140).

In other words, this is the process of white supremacy in action.

Taking my cue from critical race theory, by “white supremacy,” I’m not talking primarily about individual people who are consciously or unconsciously biased. Instead, I’m referring to the array of systemic structures and practices that grant one group unearned advantages over others by default. Here, the term “white supremacy” certainly invokes the subordination of people of color within a racist system, but it also refers to broader patterns of discrimination besides race alone. As Zeus Leonardo explains, the process of domination emerges “not . . . out of random acts of hatred, although these are condemnable, but rather out of a patterned and enduring treatment of social groups.” As writers and teachers, we need to accept that these problems are pervasive and structural if we want to move forward.

This need is all the more critical because media and communication technologies are changing in ways that will reshape our disciplines, books, and classrooms whether we like it or not. Profit-oriented corporate vertical integration strategies and the deeply-flawed power dynamics in our educational institutions will continue to infect our work. These forces intersect in ways that are far too complex for any one person to understand, and this makes it all the more important for us to work together to examine the impacts of our genres and platforms more rigorously than we have been doing thus far. It is impossible to operate in an unjust system without replicating inequality, but without more attention to how we are replicating these inequalities, the decisions we make about new media will continue to compound white supremacy in much more serious ways.

Luckily, scholars in the humanities are in the business of studying media, analyzing rhetorical contexts, and teaching different kinds of literacies. We can apply these skills to help student- and non-student audiences navigate this landscape in informed ways. Likewise, we can direct our gaze inward toward the ideologies present in our field, taking a more critical look at the narratives that take precedence when we make decisions about teaching and publishing. This, in turn, will help us to promote more socially just platforms for education and scholarship.

Calling All Strategic Presentists

We all have an obligation to self-reflexively resist structures of oppression and violence regardless of our institutional and professional affiliations. However, there’s a special place for this kind of work in nineteenth-century studies. As I’ve argued in “Where We Stand,” one reason for this is that our field’s primary source materials offer us unique insights into legal, institutional, and historical forms of exclusion that are ripe for examination and collective resistance.

Exploring the ways our institutions make us complicit in inequality and violence is all the more important for people who identify with strategic presentism as an orientation toward research and teaching. If you’ll recall from the “Critical Orientation” section of this text, many literary scholars have embraced this perspective because of the ways that it frames the research we do as intertwined with the changes we hope to see in our current environments. As we’ve heard in this project, Tanya Agathocleous describes strategic presentism as “a stance that rejects specific visions of the future in favor of illuminating the persistence of the past in the present,” and Anna Kornbluh urges us to consider how the past can “embolden us to say what must be said, in the present tense, now” (Agathocleous 93, Kornbluh, 100). It’s apt, then, that the long nineteenth century provides us with such good examples of new media forms being deployed to centralize control for the sake of profit: this is one of the ways that the past persists into the present. Just like in the Victorian era, to “say what must be said” in order to resist pervasive stratification requires us to speak truth to powerful institutions in ways that may not always lead to professional advancement.

Where do we need to turn next? I wholeheartedly agree with Andrew Miller’s argument that to approach strategic presentism productively, we need to spend more time thinking about the question, “What, in a course taught by one of us, faculty or graduate student, would lead [an] undergraduate to think ‘Yes, I can effectively address the things that matter most to me, in my historical moment, by reading Victorian writers?’” And to his point, I’d suggest that one of the necessary preconditions for that undergraduate beginning to look for a resonance between their own life and nineteenth-century studies is to feel included, respected, and not exploited by the structures of writing and teaching that Victorian Studies embraces.

To provide a basic example, a strategic presentist might explore how ableist discourse operates in Jane Eyre and draw connections to the narrative strategies that still pervade popular media. In this scenario, a scholar’s writing might sensitize readers to injustice in their present. A teacher might help students reflect on the ways that language ‘others’ people with disabilities. But this strategic presentist approach fails to enact its own values if the person advancing this stance doesn’t examine whether their communication platforms reproduce the very inequalities they attempt to highlight. Without a more robust conversation around access to scholarly materials and open platforms, the article writer in question might well circulate their work using a platform that is unfriendly to accessibility devices, meaning that people with visual impairments will not be able to access this text on equal terms.

Recognizing the complexity and complicity of our communication systems, a necessary question for the field, I believe, is “what about our platforms, written genres, subject matters, and pedagogies needs to change if we want nineteenth-century studies to be relevant to a wider range of participants at all levels?” We need to ask this question just as earnestly and just as often as we ask questions about narrative structure, metaphor, and character. And we need to discuss these questions not just using the academic genres and circulation platforms that are already entrenched in the system, but also—and especially—by exploring new ways of constructing arguments and inviting response.

What might this mean for us as writers and as teachers?

It means that we need to do more to recognize the hidden labors of inclusive scholarship and teaching. It also means we need to devote more of our critical mechanisms to improving the systems in which we operate.

What does this look like? We could provide feedback on one another’s teaching materials just as carefully as we provide feedback on our articles and monographs, paying careful attention to the ways that these teaching materials invite or forestall participation for different audiences. We can direct our writing, media analysis, and argumentation skills to the task of resisting policies that create disparate access to educational experiences and research tools. We should carefully examine the ways in which new forms of data mining can influence our work, and we should leverage the power we do have to resist the exploitation of our students and peers. Even if it means relinquishing some of the control we have previously enjoyed over our writing, we should turn to digital tools to think of ways to invite more people into our conversations than we currently admit. And we should build all of these values not solely into our lives as individuals, but into our systems, honoring this work as scholarship in our conversations and advancement structures alike.

In closing, I’ll take my cue from student-centered instructional design and propose a series of metaliteracies for nineteenth-century studies. Let’s expand them together.

Works Cited

“Adding ProctorTrack to a Canvas Course.” Wisconsin School of Business KnowledgBase, 20 June 2019, https://kb.wisc.edu/wsb/92562. Permalink: https://perma.cc/VCQ4-AQH9.

“BrainCo Partnerships and Use Cases: Neuroscience and Mental State Training in the Real World.” BrainCo, Accessed 14 September 2019, www.brainco.tech/use-cases-new/. Permalink: https://perma.cc/MY53-FJA9.

“BrainCo Focus EDU Video.” Youtube, uploaded by BrainCo, 12 January 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=fQ3eW3qQ2pk.

Finn, Kavita Mudan and Jessica McCall. “Exit, Pursued By a Fan: Shakespeare, Fandom, and the Lure of the Alternate Universe,” Critical Survey, 1 June 2016, pp. 27-38. DOI: 10.3167/cs.2016.280204.

Harrigan, Margaret. “Data on Women and Minority Faculty and Staff at UW-Madison” (2009-2018). “Faculty and Staff Trends,” Academic Planning and Institutional Research, The University of Wisconsin–Madison, 5 August 2019, uwmadison.app.box.com/s/59oqe7m5k2nfmvrxjzk89oqu4il8fu1h. Accessed 5 April 2019. Permalink: perma.cc/A8XB-K5JP.

—. “Data on Women and Minority Faculty and Staff at UW-Madison” (2008-2017). “Faculty and Staff Trends,” Academic Planning and Institutional Research, The University of Wisconsin–Madison, 5 September 2018, uwmadison.app.box.com/s/v0q9ivahc888gg50c666iy1bkzqoq46i. Permalink: perma.cc/3KFS-UJFV.

Johnson, Sydney. “This Company Wants to Gather Student Brainwave Data to Measure ‘Engagement,’” EdSurge, 26 October 2017, https://www.edsurge.com/news/2017-10-26-this-company-wants-to-gather-student-brainwave-data-to-measure-engagement. Permalink: https://perma.cc/3E5M-44PT.

Katsigiannis, Stamos and Naeem Ramzan. “DREAMER: A Database for Emotion Recognition Through EEG and ECG Signals From Wireless Low-Cost Off-the-Shelf Devices.” IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, January 2018, Vol.22, No. 1, pp.98-107. DOI: 10.1109/JBHI.2017.2688239.

Kellum, Michael. Personal interview. 4 September 2019.

Leonardo, Zeus. “The Color of Supremacy: Beyond the Discourse of ‘White Privilege.'” Educational Philosophy and Theory, Vol. 36, No. 2, 2004. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-5812.2004.00057.x.

Noble, Safiya Umoja. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism, NYU Press, 2018.

Owings, Justin. “What Drives Rage Clicks? How Users Signal Struggle, Frustration Online.” FullStory, 14 September 2017, https://blog.fullstory.com/rage-clicks-turn-analytics-into-actionable-insights/. Permalink: https://perma.cc/Y7PN-822Y.

“Piazza Playbook.” Piazza, https://recruiting.piazza.com/BestPractices. Permalink (Archive.org cache of 30 September 2017): https://perma.cc/B9PJ-4P4Y.

Slater, Niall. Learning Analytics Explained, Routledge, 2017.

“What Does ProctorTrack Monitor?” Verificent Technologies, 6 April 2018, https://verificient.freshdesk.com/support/solutions/articles/1000165260-what-does-proctortrack-monitor-. Permalink: https://perma.cc/HYQ6-CSMN.

Williamson, Ben. “Brain Data: Scanning, Scraping and Sculpting the Plastic Learning Brain Through Neurotechnology,” Postdigital Science and Education, 2019, Vol. 1, pp. 65–86. DOI: 10.1007/s42438-018-0008-5.

“The Universal Design for Learning Guidelines.” The Center for Applied Technology (CAST), accessed 2 May 2019, http://udlguidelines.cast.org/?utm_medium=web&utm_campaign=none&utm_source=cast-about-udl. Permalink: https://perma.cc/FLC4-B7AZ.

“United States Census Bureau Quick Facts (2018).” United States Census Bureau, www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/dashboard/US/RHI825218#RHI825218. Permalink: perma.cc/4TJX-K9VF.

Zambrana, Ruth Enid. Toxic Ivory Towers: The Consequences of Work Stress on Underrepresented Minority Faculty, Kindle ed., Rutgers U P, 2018.

- I explore some of the ways that Dickens and Collins addressed audiences throughout their publication cycle in my participatory edition's brief précis about serial fiction, "Reading in Parts." ↵

- Mike also happens to be my partner, and I couldn't be more grateful for his enthusiasm when I insist on having conversations about reading platforms at the drop of a hat. Thank you, Mike. ↵

- Maybe Dickens really did imagine this! The fantasy of objects telling tales about their interactions with people was common in eighteenth-century 'it-narratives,' a genre which persisted in some forms during the nineteenth century. ↵

- To be clear: I do not have this granular ability to track Javascript events in the text you're currently reading. ↵

- The company informs users that "while session replay can't pick up on mouse slamming, keyboard pounding, exasperated muttering, or other physical abuse of computer hardware, clicking multiple times on a specific element on your site is the nearest digital equivalent. Rapid-fire clicks on your site can be a clear signal of a frustrated computer user" (Owings). ↵

- Piazza literally calls this resource a "playbook." ↵

- This is an alternate universe, remember! ↵

- The idea that instructors should be elevating only the (so-called) 'best and the brightest' in their classes is pernicious, but we'll move on for the sake of the narrative. ↵

- Piazza's playbook includes some interesting elisions that follow this line of reasoning. On the one hand, they take pains to stress that students in the employer search have all opted in. And yet on the same page, they sell employers the fantasy of having all worthwhile candidates at their fingertips, saying: "the best part is, you don’t have to worry about overlooking anyone since over two million students at 2,000 schools and 90 countries use Piazza and have opted-in to be discovered by employers" (Piazza Playbook, emphasis mine). ↵

- This is the kind of person who pointedly ignores Safiya Umoja Noble's Algorithms of Oppression when they encounter it on a bookshelf. ↵

- To reiterate, Hard Times: Interactive is a hypothetical edition used for the sake of example. It doesn't exist in the present universe. ↵

- For an example of recent hypotheses and datasets related to affect recognition, see Katsigiannis and Ramzan's article, "DREAMER: A Database for Emotion Recognition Through EEG and ECG Signals From Wireless Low-Cost Off-the-Shelf Devices.") ↵

- As of September 2019, there are three pieces of Hard Times fanfiction in Archive of Our Own. FanFiction.net has an umbrella category for stories written with Dickens's narratives as points of departure, but there is currently a whopping 493 stories in that category. Archive of Our Own also includes five pieces of The Woman in White fanfiction in English and one in French, while Fanfiction.net includes 30 stories set in the world of the novel. ↵

- For more information on textbook companies' shift to selling digital platform access rather than traditional volumes, see the Publications and Provocations" section of this project. ↵

- In broad strokes, interoperable tools can work within or in concert with other tools. For more detailed information on platform interoperability, see the brief "Interoperability and Exports" explanation in this text. ↵

- As just one example, Pressbooks's Community Manager, Steel Wagstaff, recently teamed up with Billy Meinke-Lau to present a session at the Open Education 2018 Conference titled "'Open' Education and Student Learning Data: Reflections on Big Data, Privacy, & Learning Platforms." In it, Wagstaff and Meinke-Lau stress the importance of gaining informed consent from students about their data use as well as ensuring that there's an ongoing opportunity for students to review their data and change what is collected from them in future. Full disclosure: I worked closely with Steel at UW-Madison as an Open Educational Resources Teaching Assistant. In addition to being an incredible mentor, Steel frequently modeled how to ask difficult questions about ed tech and its impacts on students. ↵

- For more on how embedded content within the LMS can serve as a strategy for inviting students to participate in online knowledge production, see William Beasley's reflection, "Infiltrating the Walled Garden." ↵

- This is a topic I discuss in "Publications and Provocations." ↵

- The Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST) unpacks these concepts in detail. ↵

- This, again, is hypothetical. The critical edition I've composed for this dissertation invites student and scholar contributions openly rather than soliciting contributions individually. ↵

- Although I am working to change this, the critical edition that I have composed as a component of this dissertation is still rife with these gaps. And while I recognize that it's not feasible to represent all possible identity categories, I acknowledge that I have a long way to go to shift the aggregate focus of my critical essays away from the experiences of overrepresented groups. This is research I'll continue to do to improve this text after my dissertation is deposited. A necessary step in this process is to invite critiques and contributions from wider audiences. ↵

"Neurotechnology" is a term that Benn Williamson defines as "a broad field of brain-centred research and development dedicated to opening up the brain to computational analysis, modification, simulation and control. It includes advanced neural imaging systems for real-time brain monitoring; brain- inspired ‘neural networks’ and bio-mimetic ‘cognitive computing’; synthetic neurobiology; brain-computer interfaces and wearable neuroheadsets; brain simulation platforms; neurostimulator systems; personal neuroinformatics; and other forms of brain-machine integration" (Williamson 66, citing the Nuffield Council on Bioethics [2013]; Rose et al. [2016]; Yuste et al. [2017]).

A term used to describe a tool that can work within or in concert with another tool.