Reading Histories

Many Women in White: A Novel Evolves

Writing at the turn of the twenty-first century, D. F. McKenzie described the literary text as “always incomplete and therefore open, unstable, subject to perpetual re-making by its readers, performers, or audience” (55). McKenzie’s perspective may be familiar to you if you’ve ever sat through a friend’s ten-minute monologue about how superior the director’s cut of the 1982 film Bladerunner is to the theatrical release—or vice versa. Bladerunner is perhaps an extreme example of media’s instability: the 1992 director’s cut contained scenes originally removed from the movie, including a scene involving an origami unicorn. This additional scene shifted many fans’ fundamental assumptions about the main character in the film (Convergence 123). But a large proportion of literary scholars today think of all texts as unstable in a similar way. Media such as novels change in large and small ways over time, be it the addition of illustrations, publication in e-text format, or the release of a sequel that changes how readers view the first book. Likewise, as audiences’ attitudes change and new historical events alter social relationships, the same physical copy of a novel could land entirely differently on a different set of readers.

Because literary texts aren’t fixed objects, it can be useful for us to think about novels and communities of readers in historically-situated ways. To focus only on ‘what Wilkie Collins meant’ in 1859 and 1860 is to miss out on a rich tapestry of back-and-forth responses in the press, literary power grabs, and adaptations. As people wrote about, pirated, merchandized, and adapted the novel, conversations about the narrative changed over time. Although Collins tried to maintain authority over his text’s forms and cultural meanings, he was ultimately unable to do so. In the twenty-first century, we benefit. The variations that emerge in The Woman in White offer us a range of ways to think about reading and publishing throughout the nineteenth century and beyond.

Magazine Modifications: The Harper’s Weekly Serial Run

Variations among editions of the novel appeared before the first serial installment even reached any of its readers. In 1859, Wilkie Collins teamed up with the American magazine Harper’s Weekly to release the Woman in White in America at the same time that All The Year Round was running its serial in Britain. As Collins completed installments, he and his publishers took pains to align his two separate audiences’ encounters with the text, sending out each number to the United States in time to run the newest issues simultaneously accross the Atlantic. True, there were some slight differences in publication pace at the very end of the novel—All the Year Round published forty installments and Harper’s extended its run to forty-two parts—but by in large, readers in America and England experienced the serial on a similar timeline.

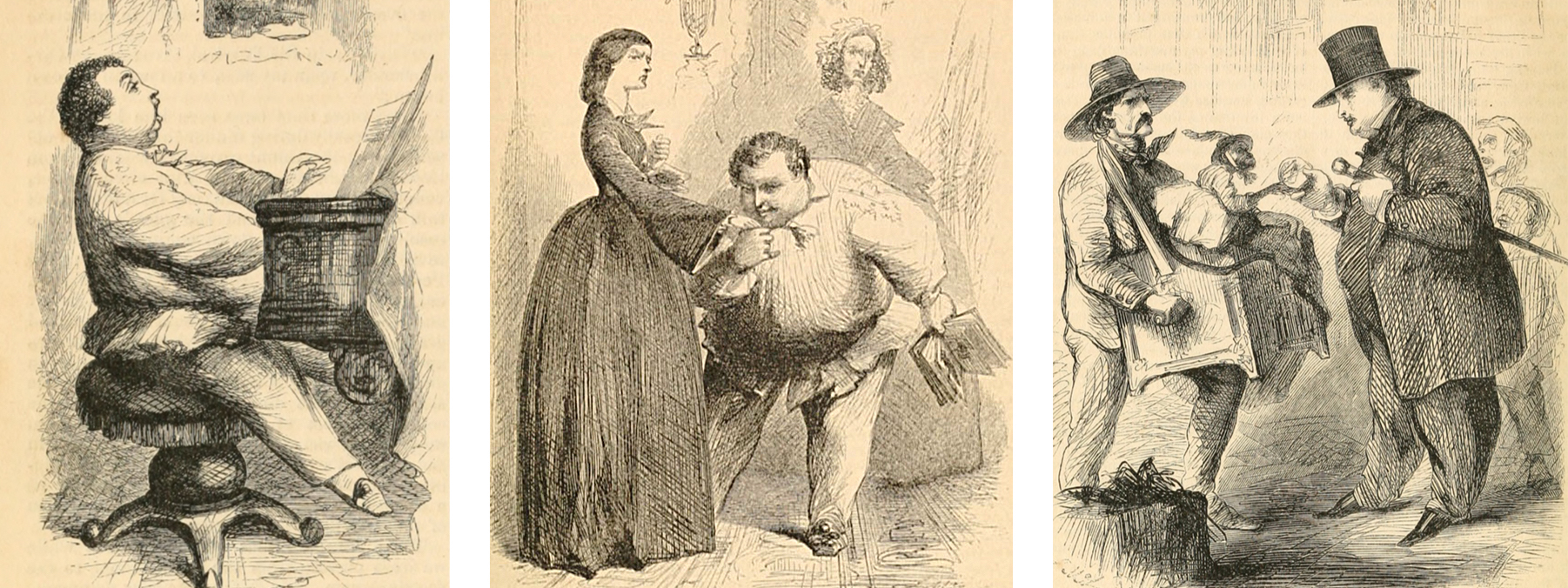

One of the key areas where these simultaneous serial releases differed, however, was in their depiction of the novel’s characters. Harper’s commissioned illustrator John McLenan to produce seventy-five illustrations of scenes and characters throughout the narrative. There tended to be two illustrations per American installment, and these images ultimately granted more visual weight to certain characters than others in any given chapter, something that inevitably affected readers’ encounters with the plot. Already a significant character in the novel, Count Fosco plays a major role in these images, appearing in as many of the Harper’s etchings as Laura Fairlie does. As far as illustrations are concerned, Fosco is second only to Marian Halcombe and Walter Hartright in the American serial’s visual landscape. Moreover, when we consider illustrations that feature only a single named character in the story, Fosco dominates. The Harper’s team was so fascinated by Fosco that they included depictions of such seemingly minor incidents as Fosco taming a dog, Fosco singing Figaro with an accordion in hand, and Fosco looking at an opera poster.[1]

When we think of what it may have been like to read Collins’s novel in serial installments, it’s useful to remember that this experience differed depending on where readers encountered these installments. Even before the novel morphed into new volume editions, the ‘original’ text emerged in a range of formats.[2] The American publishers were prescient: Count Fosco was to prove one of the novel’s most memorable characters for years to come. John McLenan’s illustrations both responded to and further catalyzed Fosco’s popularity.

From Serial to Volume

Collins published the final serial installment of The Woman in White and the three-volume edition of the novel in the same month: August 1860. In his preface to the volume edition, Collins informs readers that the text has been “carefully revised; [and] the divisions of the chapters, and other minor matters of the same sort, have been altered here and there, with a view to smoothing and consolidating the story in its course through these volumes.” The novel was successful enough that the volume edition quickly went through multiple printing runs, and during this process, Collins was able to make a series of ongoing changes to his reprints in response to reviewers who reported chronological inconsistencies in his timeline (Gasson).[3]

Collins’s changes varied in scope from segment to segment of the text. Sometimes, the changes he made to chapters in the volume edition were minimal: for example, he made no alterations at all to Marian’s narrative in the nineteenth installment. Other sections contained significant revisions of varying scope. Some of these are changes that may not substantially alter a reader’s interpretation of the narrative. In installment twenty-six, for instance, the word “doubtfully” changes to “doubtedly” in the 1860 volume, a change Collins or his editor returned to in the 1873 volume edition, which replaces “doubtedly” with “doubtingly.” These words have different connotations that may subtly alter how a reader thinks about the sentence, but the overall impact, we could argue, is fairly modest. However, other alterations may have influenced how readers felt about his characters in more significant ways.

We can see this dynamic at play in the novel’s very first serial installment. As he sends the novel’s male protagonist, Walter Hartright, out on the journey which will lead him to his love interest, Professor Pesca tells Walter that he should “marry one of the two young Misses; inherit the fat lands of Fairlie; become Honourable Hartright, M.P.; and when you are on the top of the ladder, remember that Pesca, at the bottom, has done it all!” As he revised the volume edition, Collins omitted the phrase “inherit the fat lands of Fairlie” from this part of the text. While we can’t confidently state what his motives might have been for doing so, we can think about the potential effect of this change on Collins’s audience. After reading the original reference to Hartright potentially inheriting a woman’s wealth, Collins’s serial readers may have had more reason to imagine Hartright to be someone motivated by monetary gain. In contrast, volume readers encountered a sentence that emphasized Hartright earning the favor of a woman and a voting public in his own right. As a result, the volume representation of Hartright may have seemed more valorous than his serial predecessor had appeared.

As you read the novel and its footnotes, we encourage you to think about the changes Collins made and what their effects may have been on the way the volume edition represents characters and events.

Those Meddling Critics!

Not only did the readers of Collins’s volume edition of The Woman in White encounter different words on the page than did his earliest serial readers, but many later readers also encountered the narrative alongside ongoing conversations about the novel that may have colored their interpretations as they read.

Collins was aware of this possibility and did his best to take it in hand. By the time that he was editing the text for its re-release, both he and his publishers had heard enough buzz to be confident that the three-volume edition of the novel would be a success in the booksellers’ stalls. However, Collins had concerns about how reviewers might influence his new audience. To mitigate these concerns, he included direct appeal to critics in his preface:

I am desirous of addressing one or two questions, of the most harmless and innocent kind, to the Critics. In the event of this book being reviewed, I venture to ask whether it is possible to praise the writer, or to blame him, without opening the proceedings by telling his story at second-hand? As that story is written by me. . . the telling it fills more than a thousand closely-printed pages. No small portion of this space is occupied by hundreds of little ‘connecting links,’ of trifling value in themselves, but of the utmost importance in maintaining the smoothness, the reality, and the probability of the entire narrative. If the critic tells the story with these, can he do it in his alloted page, or column, as the case may be? If he tells it without these, is he doing a fellow-labourer in another form of Art, the justice which writers owe to one another? And lastly, if he tells it at all, in any way whatever, is he doing a service to the reader, by destroying, beforehand, two main elements in the attraction of all stories—the interest of curiosity, and the excitement of surprise?

Unfortunately for Collins, his appeal produced mixed results. Multiple critics referred to his request not to spoil the novel when they wrote their review articles. Some acknowledged the virtue of allowing readers to enjoy the suspense during their first encounter with the story.[4] Other reviewers were less charitable, however. The Illustrated London News goes so far as to chide Collins for telling journalists how to do their jobs:

In a characteristic preface Mr. Collins begs the critics not to forestall public interest in his work by “telling the story at secondhand.” Go to, Mr. Collins! Such a request resembles the reticence of the reduced gentlewoman who cried “Hearthstones!” in a back street and a weak voice, and “hoped nobody heard her.” (“Literature and Art” 184)

In this description, the reviewer compares Collins to a high-born woman who has lost financial stability and must make a living by selling commodities: “hearthstones” is a term to describe Bath Brick, a cleaning product. In other words, by denying the reviews that bring him popularity and profit, Collins is being a hypocrite. Of course an entire novel will not fit into a single periodical column, the reviewer points out, but limiting the reviewer’s role is senseless: “if we dine with the lord mayor are we to go into disquisitions on the architectural features of the Mansion House . . . and never say a word about the turtle and venison, the champagne and loving-cup, we have had for dinner?” (184). Clearly, we are told, it is a reviewer’s duty—and in Wilkie Collins’s interest—to sift through the writer’s text and summarize as they see fit.

And summarize they did. Book reviews in the nineteenth century often included extended descriptions of an author’s plot and style, so spoilers abounded. Many reviews for The Woman in White described the novel’s plot and made direct references to the most surprising turns of events in the story. As you read (or reread) the novel, consider how these small-scale retellings of the novel may have colored new readers’ impressions of the tale before they ever picked up the volume edition.

Fighting For Fosco

The battle to control which version of The Woman in White was authoritative reached a climax with a theatrical production that appeared on the London stage more than ten years after the novel’s first appearance in print. Collins’s tale had inspired other dramatists to produce stage versions of The Woman in White as early as 1860, and these productions drew a flurry of attention from people eager to weigh each script’s merits and pitfalls, Collins among them (Norwood 234). In 1871, hoping to cash in on the lucrative market for his own plot and characters, Collins reasserted his authority by claiming the right to produce an official theatrical retelling (Norwood 227-28). Creating an adaptation was not an easy task, however, especially because other playwrights’ versions of the novel had already shaped audiences’ expectations of the play. Moreover, the Woman in White’s conceit of telling a story in a series of documents didn’t work for an in-person viewing experience. In order to suit a play-going audience rather than a reading audience, Collins modified and omitted numerous actions and descriptions in the play. He also added new scenes to communicate major plot points. Indeed, he even went so far as to include a dramatic death scene that hadn’t appeared in the serial or the volume versions of the book.[5]

As we have seen, Collins’s preface had already led to heated exchanges between the author and reviewers about who should or shouldn’t be allowed to describe Collins’s plot details to the public. We can see similar tensions flaring up in the expressions of support or criticism for Collins’s play that appeared in newspapers during the 1870s. As The Woman in White took on new forms, members of Collins’s audience claimed the right to decide what kind of retelling should merit the public’s attention.

Fosco’s characterization and performance became a key source of contention for viewers. Some journalists believed that Collins had done a fine job of adapting the Count to this new medium, publicly commenting that the actor who played him, George Vining, had “qualifications for the part of Count Fosco that are too generally appreciated for commendation to be needed” (“Olympic”).[6] Yet to Collins’s frustration, this was not a universal sentiment. Faced with negative reactions to George Vining’s performance as the Count, Collins felt the need to defend the play’s depiction and his actor’s performance, announcing that he didn’t consider it fair “to judge the Fosco of the drama by the Fosco of the novel” (“London, October 13” 25). To drive the point home, he added: “knowing those difficulties [of presenting a novel’s character in a stage play] as I do, I beg you will allow me to say publicly—as the literary parent of Fosco—that Mr. Vining’s representation of this part thoroughly satisfies me (“London, October 13” 25).

Such a strategy roused the ire of a reviewer from The Orchestra, who retorted, “We do not as yet see with Mr. Collins the enormity of difficulties in the way of presenting on the stage a gentle-voiced, noiseless-treading villain any more than a roaring boisterous one” (“London, October 13” 25). The author concludes by casting Collins’s authority in his teeth, arguing that Collins has no say over the aspects of Fosco’s character that readers should enjoy:

Mr. Wilkie Collins says, “Oh, but this is different kind of Fosco.” We object to different kinds of Foscos, as we should object to different kinds of Pickwicks, Micawbers, Dundrearies: we want the real original Jean Maria or none at all.[7] Mr. Collins says he is thoroughly satisfied, as though that closed all discussion. There is such a thing as also satisfying the public. (25, emphasis in original)[8]

It is worth noting that the author isn’t arguing against the existence of a Fosco adapted to a new medium, nor implying that the novel should stand on its own without any alternate forms: a satisfyingly “gentle-voiced, noiseless-treading” character like that presented in the novel is entirely possible onstage, but the reviewer claims that Collins hasn’t preserved the qualities of the character that readers found most compelling. What appears to bother the columnist the most is Collins’s own claim to final say in the matter as Fosco’s “literary parent”—to “close all discussion” when the public isn’t satisfied.

Ultimately, for every one of Collins’s efforts to claim control of his own text—by adding a preface that strove to keep his novel’s plot out of newspapers, by writing an “authoritative” play of his own, and by releasing public statements about his opinions surrounding others’ performance in his play—readers responded that their own interpretations of the novel were just as valid as the ‘original’ author’s. As scholars in the present-day, the existence of multiple Women in White gives us opportunities to understand both Wilkie Collins’s own opinions and those of his audiences in much more nuanced ways.

Works Cited

Collins, Wilkie. Jezebel’s Daughter, London, Chatto & Windus, 1880. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/jezebelsdaughte01collgoog/page/n8. Public Domain.

—. Preface. The Woman in White, Vol 1, 3rd Edition, London, Sampson Low, Son, & Co., 1860, pp. v-viii. HathiTrust, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiuo.ark:/13960/t5bc48x1g&view=1up&seq=7. Public Domain.

Gasson, Andrew. “The Woman in White: a Chronological Study,” Wilkie Collins Society, 2010, https://wilkiecollinssociety.org/the-woman-in-white-a-chronological-study/. Permalink: perma.cc/D68B-CZPE.

Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, New York U P, 2006.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth and Lisa Surridge. “The Plot Thickens: Toward a Narratological Analysis of Illustrated Serial Fiction in the 1860s.” Victorian Studies Vol. 51, No. 1, 2008, pp. 65-101.

—. “The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper’s Weekly.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 42, no. 3, 2009, pp. 207-243. DOI: 10.1353/vpr.0.0083.

Lewis, Paul. “The Woman in White In Its Original Parts,“ The Wilkie Collins Pages, 2010, http://www.womaninwhite.co.uk/. Permalink: perma.cc/HD8J-LAQT.

“Literature and Art: The Woman in White.” Illustrated London News, 28 Aug. 1860, p. 184. Proquest. Accessed 7 Apr. 2015. [Paywalled.]

McKenzie, D. F. Bibliography and Sociology of Texts, Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Norwood, Janice. “Sensation Drama? Collins’s Stage Adaptation of The Woman in White.” Wilkie Collins Interdisciplinary Essays, Cambridge Scholars Pub., 2007. pp. 221-36.

“The Woman in White.” The Critic, 25 Aug 1860, 21, 529, pp., 233-34. ProQuest: British Periodicals Database, accessed 6 April 2015.

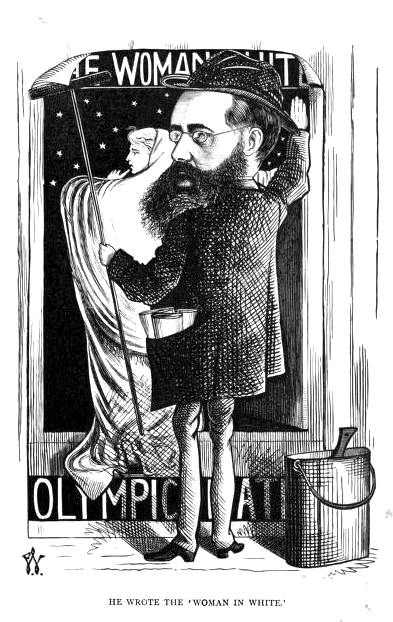

Waddy, Frederick. Cartoon Portraits and Biographical Sketches of Men of the Day, London, Tinsley Brothers, 1873. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/cartoonportraits00wadduoft/page/76. Public Domain.

Oliphant, Margaret. “Sensation Novels.” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, No. 91, May 1862, pp. 564–84.

- Paul Lewis provides a PDF collection of McLenan's images in his online project "The Woman in White In Its Original Parts." ↵

- If you're interested in the visual culture of nineteenth-century novels in general and of Wilkie Collins's American novels in particular, we recommend Mary Elizabeth Leighton and Lisa Surridge's co-written articles, “The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper’s Weekly.” and "The Plot Thickens: Toward a Narratological Analysis of Illustrated Serial Fiction in the 1860s." ↵

- If you're interested in the granular details of these revisions, see Andrew Gasson's "The Woman in White: A Chronological Study." ↵

- Among these respectful critics is the author who penned the August 4, 1860 review in The Literary Gazette, an article reprinted in this volume. We invite you to determine for yourself whether the author actually does preserve the suspense for readers as promised. ↵

- For a detailed description of this scene, see the Saturday Review's October 1871 article about the play, which is transcribed in this participatory edition. ↵

- This quote appeared in The Illustrated London News, and the article in question appears in this edition. ↵

- In this line, the Orchestra reiewer refers to popular fictional characters in other novels. ↵

- Norwood points out that Collins’s defense appeared in an October 12, 1871 edition of The Daily Telegraph as well as on later playbills for the production (Norwood 234, note 7). ↵