Chapter 4.0. Government in Britain in the Eighteenth Century: Introduction

Whereas most of the material in Module 4 examines colonial law and policy, this chapter changes the perspective by turning to British government within Britain itself. The first sections briefly address the monarchy under the Hanoverian dynasty (ch. 4.1), the royal navy (ch. 4.2), and the newly-dominant Parliament (ch. 4.3) in the period between the Glorious Revolution of 1689 and the American Revolution of 1776. Then a final, longer section presents excerpts from John Locke’s Second Treatise on Government, published in 1689 (ch. 4.4). This work became influential as a theoretical justification for Britain’s post-1689 parliamentary monarchy, and for consensual government more broadly.

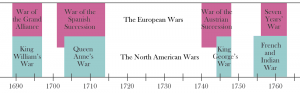

A Prosperous Century: The period from 1689 to 1776 was one of great prosperity, both for Britain and its overseas colonies. It was in this period that the United Kingdom of Great Britain (a country officially created in 1707 by the merger of the Scottish and English parliaments) became the dominant global maritime power. Britain gained this new power in part by fighting many wars against other European colonial powers, including Spain, the Netherlands, and especially France. The long-term rivalry with France continued until 1815, when British forces defeated Napoleon.

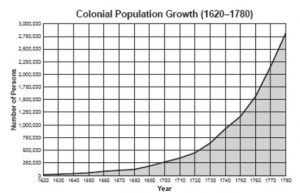

Colonial Prosperity: Despite these wars, the eighteenth century was particularly prosperous for Britain’s colonies within the Atlantic coast’s temperate zone, which later became the first thirteen U.S. states. These colonies saw rapid growth in both population and economy, growing from about 250,000 inhabitants in 1700 to close to three million by the outbreak of the American Revolution in 1775–when Britain’s own population was only about nine million. This context of prosperity may help to explain why almost all politically active Americans remained loyal, patriotic British subjects until about 1765, when the Revolutionary period began.