Ch. 3.2. Colonial Perspectives and Mid-18th-Century Debates

Adapted from Yirush, pp. 193-208.

The Rise of the Colonial Assemblies and Settlers’ Assertion of Rights

With imperial authorities unwilling to support the governors, and important colonial posts held by place seekers (or their deputies), the assemblies were able to slowly usurp executive authority. As a result, as James Henretta remarks, “by the third decade of the eighteenth century many of the American representative bodies had achieved a degree of strength and confidence which allowed them to deal with royal officials on a basis of near-equality” (Salutary Neglect, Princeton, 1972, p. 105).

This encroachment on royal authority was reinforced by the increasingly assertive rights-consciousness of the settlers. In 1735 the assembly in the new royal colony of South Carolina informed the governor that “His Majesty’s subjects in this province are entitled to all the liberties and privileges of Englishmen.” The representatives added that “by the laws of England and South Carolina, and ancient usage and custom,” they had “all the rights and privileges pertaining to money bills [i.e., laws that entailed spending government funds] that are enjoyed by the British House of Commons.”

Colonial Loyalty to the British Empire

Despite the ongoing disagreement over the rights of the settlers, it would be a mistake to view the empire in these years as beset by endemic political conflict. Indeed, the decades following the Peace of Utrecht [which ended the War of Spanish Succession, 1701-14] were ones of increasing social, commercial, political, and cultural integration in the broader Atlantic world. Under the Hanoverians (whose dynasty began in 1714), support for the monarchy grew in British America, as the settlers came to see these Protestant kings as liberty-loving rulers who provided protection in return for allegiance.

As well, this era of Walpolean rule was also the period when there emerged an ideology of the British empire as “Protestant, commercial, maritime and free.” Moreover, the British constitution in these years was the object of veneration by both domestic and foreign observers, many of whom asserted that the way it balanced democracy, aristocracy, and monarchy was peculiarly suited to the preservation of liberty.

The settlers in America were, for the most part, content with being part of a larger British world that embodied these values. As a result, they did not think systematically about the political structure of the empire, beyond a desire for a degree of local autonomy compatible with what they took to be their rights as Englishmen.

New Wars and Mid-Century Conflicts Over Colonial Governance

However, as with the earlier episodes of conflict in the empire, the exigencies of war and trade led to a renewed round of centralization in the 1740s. And as these geopolitical concerns grew in importance, so the old dream of a unitary empire gained a new purchase among imperial officials in London.

New wars broke out in 1739 pitting Britain against Spain, and then from 1744 to 1748 also against France. In 1744, the Board of Trade, concerned about colonial emissions of paper money, introduced a bill in the House of Commons invalidating all acts, orders, votes, or resolutions of the colonial assemblies that were contrary to royal instructions. This bill was never enacted, but it provoked much criticism in the colonies.

Colonial opposition was widespread, focusing not only on these attempts to limit paper money, but also on the British practice of naval “impressments” (i.e., forced recruitment, usually of sailors) and assertions of imperial control over the colonial militias.

The Independent Advertiser, the newspaper founded by a young Samuel Adams, invoked Locke and Cato [pseudonym of the British authors of a series of letters written in ca. 1720 that defended republican political ideals] against these policies. And in an anonymous pamphlet of 1747, called An Address to the Inhabitants of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, the author (most likely Samuel Adams) defended anti-impressment riots on the grounds that the people were in a “state of nature,” and had “a natural right” to band together for “their mutual Defense.”

Also in the late 1740s, Governor Clinton of new York was locked in a battle with the assembly, which had taken control of the nomination of officers, the mustering and pay of the militia, the repair of forts, and the control of Indian policy (often paying the militia directly without the governor’s authorization). As well, the assembly had used the governor’s need for money in time of war to extract concessions from him, including the right to control the disbursement of public funds.

Farther south, James Glen, the governor of South Carolina, wrote an anguished letter to the Board of Trade in 1748 complaining of the erosion of his authority at the hands of the assembly. According to Glen, the assembly had arrogated to themselves “much of the executive part of the Government.” They appointed the treasurer, the Indian commissioners, and the Comptroller of the duties on imports and exports. “Thus by little and little,” Glen warned, “the People have got the whole administration into their hands, and the Crown is by various laws despoiled of its principal flowers and brightest jewels.”

Even after peace came in 1748, concern about French power was compounded by the palpable erosion of royal authority in many of the colonies. Thus after 1748 the Board of Trade launched new efforts to restructure the empire, often based on proposals from those who had held royal office in the colonies.

Among the leading advocates of reform were two Scots, Archibald Kennedy and Cadwallader Colden, who had experienced the weakness of royal authority at first hand during their long residence in New York. Both Kennedy and Colden were concerned that local autonomy was undermining the vital diplomatic and military ties to the Iroquois Confederacy.

In his 1751 tract titled The Importance of Gaining and Preserving the Friendship of the Indians, Kennedy described the mutual assistance in war and trade between the English and the “Five nations” as an “original contract and treaty of commerce.” However, he worried that British and colonial neglect of this relationship would allow French influence with the Iroquois to grow. Charging the colonial assemblies with being “the authors of this neglect,” Kennedy called for strengthening imperial authority through the reform of the empire, a reform to be “enacted, by a British Parliament.”

Background to the French and Indian War (or the Seven Years’ War) (1756-63)

In the summer of 1753 what Kennedy had warned about came to pass, as news reached the Board of Trade that the Mohawk leader Hendrick, angry at his treatment by the Albany commissioners, had told the New York governor that the Covenant Chain, the venerable diplomatic alliance between the English and Iroquois, was no more.

Soon after receiving this news, the ministry heard reports of French encroachments in the Ohio Valley. In response, it sent a letter to the royal governors (in August 1753) to “repel by Force” any incursions within the “undoubted limits of His Majesty’s Dominions.” The Board of Trade also sent word to the governor of New York to convene all of the colonies for a conference designed to restore the alliance with the Six Nations.

The Albany Congress (1754)

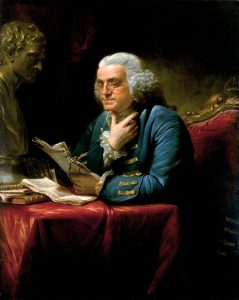

This led to a meeting at Albany in June 1754. Although originally charged only with repairing the Covenant Chain, the delegates exceeded the mandate given them by the Board of Trade and agreed to create a colonial union, largely at the urging of Benjamin Franklin and William Shirley, the governor of Massachusetts. Franklin had been thinking about such a union since the early 1750s. Indeed, he had corresponded about it with, among others, Colden and Kennedy. In early 1751, his plan for a union was printed as an appendix to Kennedy’s Importance of Gaining … the Friendship of the Indians. (Below: Benjamin Franklin in 1767.)

The Albany Plan

In 1754, on the eve of the Albany Congress, Franklin drafted a similar but more detailed plan, which provided the blueprint for the discussion at Albany. He saw union as the precondition for an expansive empire to the west. Once the Indians had faded away, he hoped that “the greatest number of Englishmen will be on this side of the water.” Franklin exulted in such a prospect: “What an Accession of Power to the British Empire by Sea as well as land! What increase of trade and navigation! What numbers of Ships and Seamen!”

The delegates at Albany agreed to create a colonial union with a “President General” appointed by the Crown, and a “Grand Council” to be chosen by the assemblies. The council had the power to choose its own speaker, and it could not be dissolved or prorogued without its own consent, or by the “Special Command of the Crown.” All acts passed by the council required the assent of the president general who would then execute them.

This new government would also have control over all Indian affairs, including the making of peace and war, the regulation of trade, the signing of treaties, and the purchasing of all land not within the current boundaries of any one colony. It would also decide on the settlement of western territories (purchased from the Indians), granting land and reserving to the Crown a quit rent. And it would be responsible for making laws for these “new settlements” until the Crown formed them into governments.

The proposed union government was also to be in charge of colonial defense, with the authority to raise and pay for troops, and the power to “levy such general duties, imposts, or taxes, as to them shall appear most equal and just.” Its laws would conform to those of England and be transmitted to the king in council for approbation, who would have three years to disallow them. However, each colony was, with the exception of ceding authority in the above areas, to “retain its present Constitution.”

Despite the backing of prominent colonial elites, the Albany Plan was uniformly rejected by the assemblies who were worried that it would undermine their autonomy by creating a new level of government with taxing powers, the ability to raise troops, control over coveted western lands, and a monopoly on relations with Native Americans.

Two of the backers of the Albany plan – the royal officeholder William Shirley and the imperially minded provincial, Benjamin Franklin – had very different responses to its demise. After failing to get the Albany Plan through the Massachusetts assembly, Shirley wrote to London that the Albany Plan did not sufficiently “strengthen the dependency of the colonies on the Crown.”

While Franklin shared Shirley’s desire for a more unified empire, he objected to the lack of colonial representation in Shirley’s plan. Franklin argued that the settlers should be represented in Britain’s Parliament.

Franklin long held onto his vision of an expansive empire predicated on colonial equality and government by consent. But in the 1760s, having come to the conclusion that a parliamentary union was impossible, Franklin was in the forefront of those proposing a federal division of authority in the empire, with the colonies having a constitutional connection solely to the Crown.