Ch. 4.3. The British Parliament in the Eighteenth Century

Although, as noted above, the Glorious Revolution of 1689 had already tipped the balance of power in England’s parliamentary monarchy away from the king and towards Parliament, the latter only gradually came to exercise its full powers. But by the mid-1700s there was no longer any doubt that Britain’s government was characterized by “Parliamentary sovereignty,” or the rule of Parliament. In practice this meant the rule of Parliament’s more powerful “lower” house, the House of Commons. In this system, both the House of Lords (the “upper” house of Parliament) and the king and the various agencies of the royal bureaucracy (Privy Council, Board of Trade, etc.) continued to play important roles. But real power–for example over both legislation and taxation–now lay with the House of Commons.

The Theory of Dual Sovereignty: King-in-Parliament. After 1689 the king or queen continued to play a role in law and politics, albeit a much reduced one. This role is usually explained by reference to the theory of dual or shared sovereignty. According to this idea, even though Parliament was now the dominant power in law-making, it still shared sovereignty with the king or queen, whose approval was needed for a piece of legislation to become law. Although the king or queen did not actually have to be present in Parliament to express his or her approval, all legitimate legislation, the statute law made by Parliament, was said to be made by the “king-in-Parliament.”

Perhaps surprisingly from a modern perspective, this terminology continued to be used even after the early eighteenth century, when royal assent to Parliamentary legislation became virtually automatic. The last statute law passed by Parliament that was vetoed by a monarch was the Scottish Militia Bill of 1707, to which Queen Anne refused her assent. And even in this case, the Queen was not so much disagreeing with Parliament as reflecting a changed view of a rapidly evolving military situation: political support for the law had weakened by the time the Queen was supposed to approve it. It should be noted however, that despite the monarchy’s loss of veto power over Parliament, most British officials continued to believe that the monarchy could veto the legislation made by the representative assemblies in the American colonies.

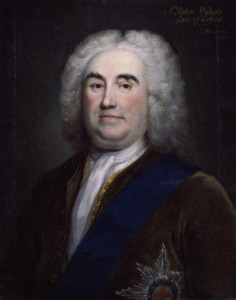

The Prime Minister: In the context of Parliamentary sovereignty, the leader of the dominant party within Parliament’s House of Commons gradually displaced the king to become the real head of Britain’s government in the sense of the person who did the most to shape national policies. Originally just one among many “Members of Parliament’ (or MPs), this leader soon acquired the new title of “Prime Minister.” Between the two main parties that dominated Parliament throughout the eighteenth century, the more pro-Parliament “Whigs” and the more royalist “Tories,” the Whigs usually prevailed. This was the case between 1721 and 1742, when Robert Walpole, leader of the Whig party, became effectively the “first Prime Minister” (as he was called later).

Four other Prime Ministers that were important in the period leading up to and during the American Revolution are listed below:

Newcastle (aka Thomas Pelham, Duke of Newcastle) (Whig), 1754-62. As Prime Minister during the French and Indian War (1754-63), Newcastle’s military strategies failed until he ceded control over the war effort to William Pitt, the Secretary of State for the Southern Department (1757-62). Pitt succeeded in part by more effectively eliciting the cooperation of the American colonists.

George Grenville (Whig), 1763-65: notable mainly for his sponsorship of the Stamp Act of 1765.

William Pitt (Whig), 1766-68. Famous for his successful leadership during the French and Indian War, Pitt was much less successful as Prime Minister (when he also became known by his new title, Lord Chatham). In colonial policy, Pitt followed the ideas of Charles Townshend, the Chancellor of the Exchequer (i.e., head of the Treasury) and former president of the Board of Trade. Together, they sponsored the Townshend Revenue Acts of 1767, which imposed duties on American imports of or trade in tea, paper, and other goods.

Lord North (aka Frederick North) (Tory), 1770-82. Prime Minister during the years immediately before the American Revolution and for most of the war (which ended in 1783), Lord North believed that most of the colonial population was loyal and thus strong measures would bring the few rebels back into line. In response to early colonial resistance (as seen in the Boston Tea Party of 1773), he sponsored the punitive Coercive Acts of 1774, which were known in the colonies as the Intolerable Acts. Even long after hostilities broke out in 1775 he continued to believe that a strong military showing would quash the rebellion.