Active Learning

36 Practical Active Learning Ideas for Large Lecture Courses

Observe & Consider

Observe & Consider

In this week’s podcast, Steel Wagstaff from L&S Learning Support Services facilitates a conversation with Janet Batzli, the Associate Director of the Biocore program; David Baum, a professor of Botany; and David Zimmerman, a professor of English, about their experiences teaching large lecture and laboratory classes. In this conversation they share best practices, offer useful ideas and tips, and provide valuable insight into how they’ve introduced active learning and increase student involvement in larger courses.

Download the .mp3 (right-click and ‘save link as’)

Observe & Consider

Observe & Consider

Common Problems with the Large Lecture

It’s probably no surprise to you that the large lecture has received heavy, sustained criticized as an instructional format. And yet, it has survived, like other unhelpful nuisances (Hello flat-earth theorists, Sunny Delight, the electoral college, and the mosquito!). You’ve all had (and hopefully shared) horror stories, seen examples of disengaged teaching, passive participation (or worse) from students, and felt the frustrations of trying to fit a round peg (effective, engaged pedagogy and meaningful learning) into a round hole (poorly designed spaces, overenrolled courses, and unprepared or disinterested students). Some of the biggest problems with large lectures are the following:

- the limits of student attention

- poor rates of retention & transfer

- encourages learner passivity or distraction

In the following sections, we’ll examine some specific, practical ideas that address these problems and have been demonstrated to improve learning outcomes in large lecture courses.

Problem #1: The Limits of Student Attention

Researchers studying the learning experiences of college students in standard lectures found that after an initial settling-in period of five minutes, students readily assimilated material for the next five minutes. Ten to 20 minutes into the lecture, however, confusion and boredom set in and assimilation fell off rapidly, remaining low until a brief spike just before the lecture’s end. These findings have been confirmed and verified in a number of subsequent studies. If we know that learning is uneven or even ineffectual when spread continuously in a 50 minute (or longer) lecture without breaks or variations, why continue doing it?

Solutions:

The most basic solution to this problem is to intentionally break the lecture every 15-20 minutes, inserting brief demonstrations or short writing and reflection exercises followed by class discussion. There are a number of formal strategies that take this basic approach, including the following:

- The Feedback Lecture: Initially developed at Oregon State University in the late 1970s, the feedback lecture is built around a supplemental study guide that provides assigned readings, pre- and posttests, learning objectives, and an outline of lecture notes. The basic format consists of two mini-lectures (each roughly 20 minutes in length) separated by a small-group study session where students respond to discussion questions focused on the lecture material provided by the instructor. These questions can take many forms, from standard open-ended questions to having groups of two or three students begin by considering a judgment question and then building a specific response based on specific information or evidence presented in the course. This large-lecture method was enormously popular among students who experienced it: 99% of students stated they found the discussion break either “useful” or “extremely useful” and 88% indicated that if given a choice, they would prefer a course taught using the feedback lecture over a traditional lecture course.

- The Guided Lecture: In a guided lecture, the instructor begins by announcing the lecture’s primary objectives, which students are encouraged to record. The instructor then asks students to put away their writing utensils and electronic devices and actively listen to a dynamic lecture which lasts approximately one-half of the class period (25-30 minutes). Their instructions are to try to determine the major concepts presented and remember as much supporting data as possible. At the end of the lecture, students are given five minutes to recording all of the salient points of the lecture they can recall. After these five minutes have passed, students are placed in small groups where they work to conceptually reconstruct the lecture, listing its major points and relevant supporting data. Once they’ve done this, students then prepare their complete lecture notes, with the instructor making herself available to resolve questions as they arise. As a homework assignment, students are asked to reflect on the lecture later in the day and to write the major concepts and relevant supporting information in narrative form (some instructors ask them do this without making reference to their lecture notes). At the beginning of the next class, faculty may instruct students to write a brief response to a question or problem based on the previous lecture and then pair with a partner seated on the left or right to compare and discuss their responses.

- The Responsive or Interactive Lecture: There are a number of variations on this approach. In one, instructors devote one class period per week to answering open-ended, student-generated questions on any aspect of the course (see this course’s module about effective online discussion for some ideas about how to do this online). A few rules apply: all topics must be couched as questions and while any student can submit as many questions as they wish, they were also asked to briefly explain why they considered the question important. The class then ranks or orders the question based on relevance or interest, and the instructor responds to as many topics as time allows. Another variation of an interactive lecture can begin with students brainstorming what “they know or think they know” about a given topic while someone records the contributions in a location where all participants can see them. The instructor then uses these contributions to build a conceptual framework around the topic and correct any observed misconceptions.

Resources:

- Education professor Charles Dennis Hale has assembled a very thorough chapter outline on several types of interactive lectures. As prose, it’s not the smoothest read, but it’s packed with resources, references, and has an excellent bibliography.

- William Cashin, an emeritus professor at Kansas State, has written a short IDEA paper on effective lecturing that includes several useful tips and ideas as well as a helpful bibliography.

Problem #2: Poor Rates of Retention and Transfer

Want some depressing news? What do students remember from a course a few months after they’ve completed it? The research shows that in most cases the answer is “almost nothing.” While it’s unrealistic to expect all of our students to remember all (or even) most of our lecture content, most of us want to believe that our teaching does make a substantial difference in our students’ development, that what we do and say can positively impact their long-term memory and that what they learn in our context- and discipline-specfic class will be useful to them in other parts of their lives (what educators and psychologists call positive transfer). The researchers who have studied the difficult problems of content-knowledge recall and skill transfer have found that there are things that you can do, even in large lecture classes to positively impact what students learn (and retain) even after they’ve taken your final and destroyed thousands of brain cells over their winter or summer break.

Solutions:

One surprising research finding from the past few decades has been that testing seems to have an almost magical ability to improve student learning. Researchers don’t understand exactly why they work in this way, but in several studies, students who are asked to take a quiz or test immediately after a lecture were found to have much higher rates of long-term retention, for both factual and conceptual knowledge.Students do experience considerable anxiety about tests and quizzes, some of which is probably productive, and some of which probably isn’t, but here’s the remarkable thing: testing seems to have the same positive impact on learning even when their results aren’t heavily weighted as part of their final grade. Cognitive psychologists have come to describe the effect as “the testing effect” of “testing-enhanced learning.” David Myers describes some of the basic principles behind the testing evidence in this engaging 5 minute film:

UW-Madison psychology professor Brad Postle recently received a DoIT Engage award to implement a testing-enhanced learning plan in a large undergraduate lecture course he teaches and found that it had a dramatic effect on student performance, doubling the number of ‘A’ grades earned in his course compared to prior semesters, drastically reducing the number of students who failed the course, and improving overall performance. You can watch a brief video in which Dr. Postle describes the project’s impact on student learning at the DoIT engage site.

When it comes to applying the evidence for testing-enhanced learning in your large lecture courses, here’s our advice: use quizzes, exams, and tests as regular parts of your lecture plan, including for non-evaluative purposes. Many instructors on the UW campus and elsewhere, particularly in STEM courses, have begun integrating student response systems (a fancy name for clickers and clicker software) into their lecture plans, with positive initial results. Regular low-stakes tests and quizzes provide crucial self-assessment and evaluation opportunities and allow students to practice/demonstrate content mastery. Composing these exams can even be a collaborative assignment for students. Ask students to make up a test or suggest test questions that require higher-level thought about concepts contained in their reading assignments. Put learners in groups and ask them to take each others’ tests. Students can then discuss their exams tests with partners, verify answers, question wording, see if tests relate well to the reading assignment, and share particularly good (or difficult) questions with the whole lecture session.

Resources:

- Read a review of the literature documenting the testing effect published in Perspectives on Psychological Science in 2006 by Henry Roediger and Jeffrey Karpicke, psychology professors at Washington University in St. Louis. Roediger also directs the Test-Enhanced Learning in the Classroom project, which runs a website listing their several publications.

- Read Shana Carpenter’s brief (5 page) 2012 review of the evidence for testing’s impact on positive transfer (learner’s ability to apply their learning to new situations).

- German educators designed a study testing the effectiveness of online quizzes used in conjunction with a large lecture course. Students in the interactive quiz lectures reported higher levels of satisfaction with the course, and also reporting higher levels of attention, activity and perceived learning success. Because it was conducted by Germans, it was very precise.

- Read Shanta Hattikudur and Bradley Postle’s description of the effects of Test-Enhanced Learning on their cognitive psychology undergraduate lecture course at UW-Madison.

- DoIT’s Engage program also hosts a very useful page about student response systems (clickers) and their impact on student learning.

- In 2012, University of New England professor Shawn Keogh published a review of the existing literature about the classroom use of clickers, highlighting major perception and outcomes of their use, and empirically documenting their usefulness in the management discipline.

Problem #3: Encourages Learner Passivity

Want even more depressing news? Consider what the typical student does in a typical lecture to meaningfully engage their higher-level cognitive abilities. Research indicates that left to their own devices, most students do almost nothing that contributes to long-term meaningful learning. In some classes they’re little more that amanuenses, furiously transcribing the lecturer’s slides word for word from projection screen to their notebooks. In other lectures, they passively watch, listen, or receive information, taking in a performance as if it were being televised. In other lectures, they drift off into their own private worlds, sleeping, chatting or texting with peers, or browsing the web on personal electronic devices. Without proper design, guidance, and instruction, large lectures can actually discourage meaningful engagement and establish (or confirm) poor learning patterns and habits.

Solutions:

A few paragraphs up we discussed the idea of the interactive lecture and our podcast guests shared a number of activities that have helped them discourage passivity in their large lectures and laboratories. David Baum’s idea of ‘barbed content’ is a particularly vivid image, and there are several ways that you can add barbs to your lecture ideas and help students engage intellectually with your lecture material and take up a more active, constructive role as learners in your course. In the video below, David Abbott, a professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology at UW-Madison, discusses ways that he recently transformed his large lecture course into a more interactive, active learning environment with help from an DoIT Engage award.

In addition to the ideas that Dr. Abbott described and those described in this week’s podcast, we’d also suggest trying any or all of the following:

“Where Am I Stuck?” Activity: Fancher Wolfe, now an emeritus economics professor at Metropolitan State University, developed a helpful activity in which he would regularly break students into small groups (4-6 students per group) 15 minutes before the end of class. He would give each person in the group two minutes to tell others where they were feeling stuck in the course, what they presently found difficult or confusing. If a student feels everything is clear, she can pass. One student keeps time and another acts as the group’s recorder. Once each member has spoken, the instructor gives them three minutes to try to reach a consensus on a particular sticking point that’s troubling the majority of the group members which the group’s recorder can then report back to the larger group or share directly with the instructor, who adjusts future lecture plans accordingly.

Large-Lecture Activities: With careful planning and some advance preparation, large lecture settings can be effectively used for staged debates, simulations, role playing, or even place-based instruction or field trips (which Janet Batzli discusses in this week’s podcast). One way to approach these activities is to build the lecture around a problem or challenge that can best be solved with ideas or concepts introduced during the lecture. Instructors prepare the group with a minilecture and then pose or introduce a specific, real-world problem. The instructor might then divide the class into two or more large groups, giving each a well-defined role in and asking them to develop a position or describe a course of action. Once the groups have had sufficient time to discuss and develop their ideas, the instructor can ask each group for participants to represent their group’s position in whatever activity format the instructor has chosen for that class: whether it be a formal debate, a simulation, role playing, or even a panel discussion.

Structured Note-Taking: Even in lectures where the instructor is the primary speaker or actor, students need not be passive listeners only. Instructors can do a great deal to train students in the art of active listening and help provide useful guidance when it comes to effective note taking and study habits. There’s a wide and extensive literature describing several different note-taking and active listening methods, which generally indicates that students who develop the habit of succinctly summarizing lecture content and those who ask and answer questions in their note taking practice perform better than untrained students who tend to simply copy and lecture material verbatim for later review. Something as simple as building structured pauses into lectures for students to consolidate their notes and reflect on their learning can make a surprising difference. In one study, an instructor paused for two minutes on three occasions during each of five lectures; the intervals between pauses ranged from 12 to 18 minutes. During the pauses, students discussed and reworked their notes with a peer, with no direct instruction or interaction with the lecturer. At the end of the lecture, students wrote down everything they remembered from the lecture in three minutes. In two separate courses repeated over two semesters, the results were striking and consistent: students hearing the lectures where the instructor paused did significantly better on both the free-recall quizzes and an end-of-semester comprehensive test (the difference in mean scores was large enough to make a difference of up to two letter grades). Next week we’ll discuss even more writing and reflection activities in greater detail, but for now you can read that study as well as a comparative study of note-taking methods in the resources section below.

Resources:

- Legendary education professor Jim Eison has written a fantastic, detailed description of active learning techniques for large lectures, including references to the pause procedure (described in literature from the late 70s-early 80s).

- In 1992, Alison King, then a California State education professor, published a comparative study of the effectiveness of different styles of notetaking in the American Educational Research Journal.

Practice & Apply

Practice & Apply

Guided Self-Assessment: Active Learning in Large Lectures

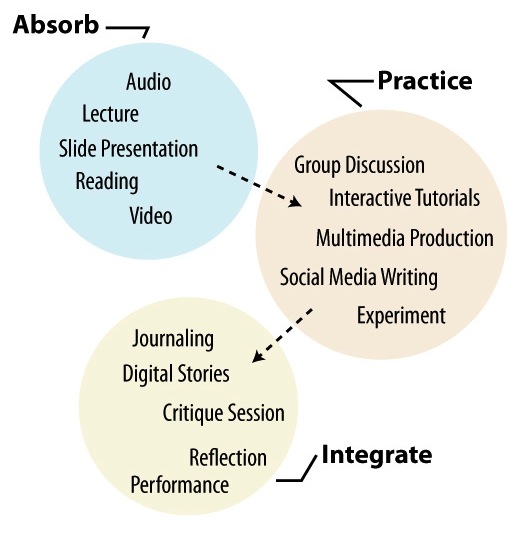

Visualization of active learning activities. Concepts adapted from William Horton’s E-Learning by Design, 2nd ed., 2011.

Absorb activities are a way to communicate essential course concepts so students are both informed and inspired. Activity objectives in this domain involve words like infer, interpret, paraphrase, recall, detect, & attend.

Practice activities help students focus on taking the information they have learned and actively work with it. Practice objectives in this realm include words like discover, verify, organize, discuss, develop, & apply.

Integrate activities allow students to apply what they’ve learned in a realistic context or link new information to what they already knew. These activities are generally flexible to allow students to make a personal connection with course concepts.

Instructions:

Think about a lecture that you give or one that you’re familiar with as a student. Next, break the lecture down into its component parts. Use this worksheet to record and adapt the lecture’s main elements. Identify areas that you would like to make more active.

Media Attributions

- 3-modesB