Active Learning

30 Active Learning Models & Approaches

Observe & Consider

Observe & Consider

In the following podcast, Steel Wagstaff from L&S Learning Support Services facilitates a conversation about active learning approaches with Jim Brown, an assistant professor in English; Mary Claypool, a recent Ph.D. in the Department of French and Italian; and Beth Fahlberg, a clinical associate professor in the School of Nursing:

Your browser does not support HTML5 audio. If you’d like to listen to the file, use the download link below.

Download the .mp3 (right-click and ‘save link as’)

Observe & Consider

Observe & Consider

Models of Active Learning

Active learning can take many forms, follow different models, and serve many different instructional goals. Many of these approaches have areas of overlap with each other and draw on similar pedagogies that focus on student-centered instruction and course learning objectives. In this way, active learning module and lesson design planning relies heavily on the >backward design process (discussed at greater length in a chapter from our section on Blended Learning, where instructors will identify and craft key learning objectives for their students and then work “backward” to design assessment opportunities and in- and out-of-class activities that respond to these learning objectives and help the students be successful in achieving them. This helpful Educause article on active learning design by three Virginia Tech educators briefly touches on a few of these key design elements and how some might be unique to the active learning environment.

We’ll explore these approaches in greater detail and look at some concrete examples of active learning ideas for both smaller courses and large-lecture sections in later chapters, but here are a few active learning models and pedagogical approaches to get us started:

Collaborative Work

Collaborative active learning emphasizes structured group work, sharing, and project coordination in order to solve an academic task or to learn or develop a new skill. This group work can take the form of pair work, small groups of students, or all-class collaboration. Many of these approaches draw on the use of partnerships and targeted working groups in the classroom environment and leverage the community-building energies that these groups foster. The effect can be increased student engagement, student accountability for their participation and group contributions, and enhanced class cooperation.

Examples of collaborative work activities include:

- Peer tutoring

- Class debates

- “Share out” and interactive discussions

- Group projects

- Student- or group-led lessons (or portions of a lesson)

Some teaching approaches that can work well with collaborative work activites are: inquiry-based teaching, peer feedback or evaluation strategies, independent (or student-led) project assignments, and student-driven pedagogies. A few great examples of UW-Madison collaborative work environments or resources that model collaborative work are the DesignLab (in College Library), The Writing Center, and GUTS peer tutoring.

Problem- & Inquiry-based Learning

Problem – and inquiry-based learning activities have a flexible format but typically follow a pattern of diagnosis and evaluation of a challenge or problem. The students would be asked to

- define or identify the problem or challenge,

- diagnose potential reasons for this problem,

- brainstorm and evaluate alternative solutions or options, and

- choose the most appropriate solution and justify the reason for their choice.

Problem- and inquiry-based learning asks the students to assume responsibility and a higher level of engagement with their learning process (and the teaching process) while also encouraging critical assessment, inquiry, and skillful analysis of course materials and topic content. These types of activities can often be very interactive and deeply rewarding for the students, since they frequently feel a sense of accomplishment while completing and sharing their findings.

Some examples of problem- and inquiry-based activities are:

- Case study analyses

- Independent projects

- Mock trials

- Strategic writing reflections

Some teaching approaches that can work well with problem- and inquiry-based learning activities are: discovery or self-exploration activities or processes, technology-enhanced role simulations, case-centered instruction, and model scenario training. Disciplines like physics, economics, nursing & medicine, and sociology often rely on problem-based learning strategies (as well as many other disciplines). One great UW resource for crafting problem- and inquiry-based learning activities is the Case Scenario Builder/Critical Reader tool created by DoIT Academic Technology.

Games & Simulation Activites

Games and simulation exercises immerse students in responsive active learning environments that frequently simulate a real-life experience. These activities can help create learning situations that would not otherwise be available in the traditional classroom and allow safe, fun opportunities for learners to develop, practice, and improve coping skills for potentially stressful, unfamiliar, complex, or controversial situations. In addition to helping augment course materials, these types of activities can encourage personal initiative and often generate very high levels of motivation, engagement, and enthusiasm.

Some examples of games and simulation activities are:

- Technology-enhanced role playing (avatars, for example)

- Place-based gaming

- Game or puzzle creation

- Digital storytelling media

Some teaching approaches that work well with games and simulation activities are: problem-based learning (see above section for some additional details), technology-enhanced instruction, “third place” classroom teaching concepts (the idea that instruction can happen in a third space that is situated in or approximates the real world and is neither in the classroom or online). In addition to technology-enchanced gaming, other examples of games and situated learning activities can run the gamut from in-class mini dramas or play acting to study abroad scenarios. A few UW-Madison examples of game and situational learning resources include DoIT’s ARIS program, WisCER’s Epistemic Games Group, and Games+Learning+Society.

Read an article about epistemic games and their potential to help enhance student learning from the Epistemic Game Group in the Wisconsin Center for Education Research (WCER): “Assessing Learning in the 21st Century”

Space & Format Interventions

This model of active learning is a broader catchall term that refer to both changes in the physical environment in a learning space as well as adjustments of content and delivery to accomodate more active learning. Space and teaching format interventions can involve reorganizing and reconceptualizing the classroom space so that the environment better encourages independent student work, allows for a fluid and flexible use of class time and work, and fosters collaboration amongst students. This reorganization can range from rearranging class furniture and making other design modifications to establishing new teaching and learning “movements” which alter the classroom’s ‘traffic flow’ to simply recognizing the different ways that people might naturally occupy a space when they’re actively engaged in the learning process.

Some examples of space and format interventions are:

- Lab-type classrooms

- Enhanced or Interactive Lectures

- Emporium or collaboration areas

- Studio space

- Moveable furniture classrooms

Most any active learning teaching approach (or traditional teaching approach, for that matter) can work well in an active learning space. We have a growing number of these active learning spaces at UW-Madison, including the Wisconsin Collaboratory for Enhanced Learning [WisCEL] spaces in College Library and Wendt Commons.

If you’d like to learn more about these active learning spaces, check out “Learning in libraries: New center marries instructional and study space,” a recent news article about the WisCEL space in Wendt Commons.

Observe & Consider

Observe & Consider

If you’d like to read more about active learning and explore details of some of the models and approaches mentioned above, here are some additional resources that we’d recommend. Again, we’ll be discussing aspects of these models and approaches in depth in Weeks 2-3 when we address specific active learning goals, pedagogies, and activies in small classrooms, active learning spaces, and large lecture courses.

- A brief summary digest of Charles Bonwell and James Eison seminal 1991 book, Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom.

- Key ideas from Joel Michael and Harold Modell’s Active Learning in Secondary and College Science Classrooms: A Working Model for Helping the Learner To Learn.

- We can’t recommend the outstanding National Resource Council publication How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience and School highly enough. You can download the full-text of the book or check out these specially recommended chapters: on learning generally [Chapter 1], on designing active learning spaces [Chapter 6], and on teaching with technology [Chapter 9].

Guided Self-Assessment

Practice & Apply

Practice & Apply

As we’ve seen in the previous section, there are a number of approaches to making learning more active. In this activity, you’ll think though the implications of how a part of your course might work when using one or more of the four models of active learning. Keep in mind that high impact, low risk adaptations are ideal.

Instructions:

-

Download the Worksheet

Active Learning Guided Self-Assessment Worksheet To get started, download the Guided Self-Assessment worksheet to record your information, or use your own system to write down your notes.

-

Recall the Four Models of Active Learning.

Refer to the previous page for examples of how to align active learning with learning objectives. For quick reference, the four models for active learning are:

- Collaborative Work

- Problem- & Inquiry-based Learning

- Games and Simulation Activities

- Space and Format Interventions

-

Assess the Risk and Impact of Adaptation or Redesign

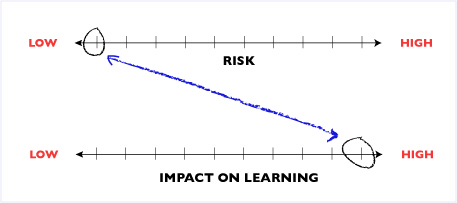

Take note of where your changes fall on the spectrum of risk of implementation and impact on learning.

Risk of Implementation and Impact on Learning Spectrum

The ideal interventions combine low risk and high impact on learning -

Next Steps & Discoveries

What did you learn from this activity? What did you find out about the alignment of your ideas with their potential impact?

Media Attributions

- 3-modesB