Active Learning

29 History & Context for Active Learning

Observe & Consider

Observe & Consider

The idea that meaningful learning requires active engagement is an ancient one, and while it is not especially revolutionary, our contemporary educational practices don’t always reflect what we believe or know about active learning. On this page, we’ll take a look at some of the thinkers and ideas which have been most influential on our current ideas about active learning and effective student-centered instruction.

Active Learning and ‘Constructivism’

The term “active learning” and the related idea of “student-centered” (rather than “teacher-centered”) learning became prominent nodes of interest among educators during the late 1970s and early 1980s. As their era’s leading buzzwords, they filled much the same role that blended learning and MOOCs are filling today. Over the past few decades, an increasing number of teachers, educational researchers, cognitive psychologists, and instructional designers have shown sustained interest in developing, propagating, and evaluating models of teaching and learning that afford greater opportunities for participation, exploration, and collaboration to students and learners.

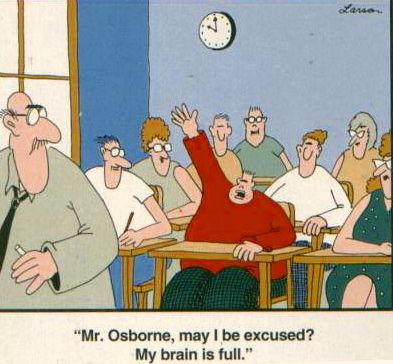

One of the most important contributions that proponents of active learning have made to our idea of effective education has been its revision of the defining metaphors we use to imagine teacher/student interaction. For some educational reformers, like Paulo Freire, prominent teaching methods of their day seemed to be founded on what they described as a “banking model.” In this model, teachers behaved as if information could be directly transmitted from subject experts to novice learners, who passively received and deposited their lesson’s content, filing it away or memorizing it for later withdrawal. Some even visualized education as the filling of smaller, mostly empty vessels [students] with content knowledge poured out from a large, overflowing vessel [instructor], an idea that’s satirized deliciously in the Far Side cartoon below:.

In the place of these metaphors of teaching and learning, proponents of active learning have stressed that learning is an active process, and have developed metaphors of teaching and learning rooted in a “constructivist” philosophy, which posits that knowledge is never merely transmitted between individuals, but is a dynamic capacity constructed by the learner using internal thought processes and acting on environmental stimuli. In other words, learning involves the active construction of meaning by the learner, who combines new information with existing mental models in order to make sense of the world that they encounter. Instead of receiving and importing ready-made knowledge, learners build mental representations or models of the “real world” that they use to solve problems. These representations can be well or poorly formed but are continually accessed and updated by each individual learner, including the individual(s) responsible for filling the traditional role of the instructor. In the sections below, we’ll look at five thinkers whose ideas have provided many of the underpinnings of modern constructivist ideas of learning.

John Dewey

In American education, one of the earliest and most influential advocates for what we would now call ‘active learning’ was the philosopher and educator John Dewey [1859-1952]. In his influential book Democracy and Education [1916], Dewey wrote that learning means something which the individual does when he studies. It is an active, personally conducted affair.

Dewey believed that people come to understand themselves and the world through their interactions with other people and things in the world, and that the purpose of education is to produce an environment in which useful interactions could be developed and sustained. He emphasized the need for active learning when he claimed that there is no such thing as genuine knowledge and fruitful understanding except as the offspring of doing. The analysis and rearrangement of facts which is indispensable to the growth of knowledge … cannot be attained purely mentally—just inside the head. Men have to do something to the things when they wish to find out something.

To learn more about Dewey’s ideas, we recommend reading “My Pedagogic Creed” [1896], which succinctly presents many of his ideas about the purpose of education, or his book Democracy and Education [1916].

In the following video, A.G. Rud, Dean of Washington State University’s College of Education, describes Dewey’s lasting impact on education:

Maria Montessori

The Italian doctor and educator Maria Montessori [1870-1952] developed an educational philosophy in the early part of the 20th century that has had a massive impact on the way that chidren and young adults around the globe experience learning. In a series of influential books she published between 1909 and 1917, Montessori laid out what she called a “scientific pedagogy” that emphasized mixed-age classrooms, student autonomy, uninterrupted opportunities for creative exploration, and carefully designed learning environments. Over the subsequent years, her educational ideas gained traction across several continents, so that today that are an estimated 30,000 schoold currently using some version of Montessori education. In her book, Education for a New World [1946], Montessori provides a good summary of her basic ideas regarding the ideal student-teacher interaction by declaring that Education is a natural process spontaneously carried out by the human individual, and is acquired not by listening to words but by experiences upon the environment. The task of the teacher becomes that of preparing a series of motives of cultural activity, spread over a specially prepared environment, and then refraining from obtrusive interference.

If you’d like to read about Montessori’s approach to pedagogy in her own words, we recommend her book The Montessori Method [1912].

Gilbert Ryle and the Distinction Between Knowing How and Knowing That:

In 1945, the British philosopher Gilbert Ryle [1900-1976] published an influential lecture in which he argued that philosophers had not paid enough attention to the common-sense difference between two kinds of knowledge: knowing that something is the case and knowing how to do things, a distinction which has come to be known as the difference between declarative and procedural knowledge (knowing that and knowing how, respectively). In Ryle’s lecture, he observes that I can’t be said to have knowledge of [a] fact unless I can intelligently exploit it. … Effective possession of a piece of knowledge-that involves knowing how to use that knowledge, when required, for the solution of other theoretical or practical problems. There is a distinction between the museum-possession and the workshop-possession of knowledge.

Ryle’s ideas, developed at greater length in his subsequent work, especially The Concept of Mind [1949], have been of special importance for psychologists and educators interested in developing active learning processes which facilitate meaningful learning by increasing procedural rather than declarative knowledge.

Jean Piaget

The Swiss psychologist and educational philosopher Jean Piaget [1896-1980] is best known for his study of children’s cognitive development, and his interest in how learner’s construct knowledge. For Piaget, knowledge was the ability to modify, transform, and operate on an object or idea in a way that grants the learner understanding through the process of use or transformation. He believed that learning was an activity, and that in emerged from experiences the learner had, both physically and logically, with objects around them. In a late-career interview with Jean-Claude Bringuier, Piaget stated that Education, for most people, means trying to lead the child to resemble the typical adult of his society … but for me … education means making creators … You have to make inventors, innovators—not conformists.

Piaget’s ideas have had an enormous influence on our contemporary understanding of childhood development and our ideals of teaching and learning. To understand more about Piaget’s thought, we’d recommend looking at The Moral Judgment of the Child [1932], one of his most significant books.

You can watch Piaget explain his constructivist position, with examples from experiments conducted with young learners below:

Lev Vygotsky and the Zone of Proximal Development

Another developmental psychologist whose ideas have been particularly important to contemporary ideas about active learning was Lev Vygotsky [1896-1934]. While Vygotsky produced several works of great importance, his most influential idea is probably his conception of the Zone of Proximal Development [ZPD]. The zone of proximal development is the distance between what an individual learner is currently able to do independently and what they have shown an ability to do under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers. Vygotsky believed that what children are able to do with the assistance of others is even more indicative of their present level of mental development than what they can do alone. The zone of proximal development offers a way of thinking about what kinds of things an individual is best prepared to learn and master for themselves, and helps teachers and learners identify knowledges, skills, or abilities that are currently at the upper level of a learner’s competence. In other words, the zone of proximal development focuses not on what I can already do, but what I am almost able to do. For most learners, their zone of proximal development is always changing, since the things that they can perform today with assistance they will soon be able to perform independently, growth which prepares them for further learning. This idea has great relevance for models of active learning, since they often emphasize the value of collaborative exploration and peer teaching and focus on the the practical acquisition of procedural knowledge.

Share & Connect

Share & Connect

If you’ve made it this far, congratulations! In many ways this page focused on declarative knowledge and employed a lot of the techniques and approaches associated with older, more passive forms of instruction that we disparaged as being part of the “banking” model in the opening paragraphs. So here’s something for you to do if you’d like to make this a more active, participatory experience:

Step 1: Reflection

Think back to the most significant educational experiences you’ve had. As a learner, who has been particularly influential in your life? It could be a parent, a grade-school teacher, a college professor, a roommate, a fellow member of a bookclub, a river rafting guide, anyone whose teaching style made a difference for you, who initiated meaningful learning. Do you have someone in mind, someone who helped or inspired you to become an active learner? Good.

Step 2: The Gratitude Project

Make a plan to communicate to this person how their influence on your learning has benefited you. Tell them, sincerely, how they made a difference in your life and thank them for what they’ve done. There are many ways to do this: write a letter (anonymous or signed), send an email, make a phone call, visit face to face. You choose the means of communication, but the challenge is the same for everyone: to express gratitude to this guide or teacher.

Step 3: Trace a Genealogy of Influence

The next step in this challenge involves becoming an active learner again. As a part of your exchange with this influential guide or teacher, ask them who or what influenced their teaching style, approach to learning, or educational philosophy. Find out how they become the guide or teacher that they became, who or what influenced their growth and learning, and share your own experiences and insights where relevant. In our experience, this conversation can be just as rewarding as Step 2, and sometimes even more illuminating.

For example, when I [Steel] was doing this activity for myself, I chose my mother, and was surprised to hear her tell me about how she had started and run something called a “joy school” for me and several neighborhood children when I was very young. Without my even knowing it, Richard and Linda Eyre, the founders of the joy school movement, had been indirect influences on my own early learning experiences, and I’ve made it a goal to learn more about this program, its founders, and its educational philosophy during the coming weeks.

Step 4: Repeat and Revise

We’ve tried to show on this page how many of the best ideas and practices of the contemporary higher education have their roots in the experiments and convictions of teachers from the past. We believe that this is true for almost any idea or practice, that nearly everything we believe, know, and do has a rich and interesting contextual history, a past worthy of exploring. As you investigate the roots and influences of the experiences and knowledges that are most meaningful in your own life, you’ll find unexpected things that you’ll want to learn more about. When it comes to investigating the impact and influence of meaningful teachers, the potential for infinite regress is immense (it seems to be a case where it really is turtles all the way down!) We hope that you’ll continue broadening and deepening your exploration and that you’ll share the fruits of your inquiry by encouraging others to branch out, dig deeper, and connect more widely as they take responsibility for their own active, meaningful learning.

Media Attributions

- 3-modesB

- 3-modesC