Active Learning

31 Why Use Active Learning in Smaller Classes?

Observe & Consider

Observe & Consider

Teaching in smaller classes offers all kinds of advantages: instructors can usually learn each student’s name, tailor their instruction to class interests and ability levels, manage collaborative and cooperative projects, and more easily have meaningful interactions, including discussions, with the whole class. While smaller class sizes seem in some ways to lend themselves naturally to more effective active learning, there’s no guarantee that a class will be actively engaged in learning simply because there are fewer students. Similarly, we should be careful not to confuse activity with learning; it is not the case that just because students are actively doing things that they are experiencing meaningful learning, in fact, some kinds of activity may actually detract from learning goals and prove detrimental in the long term. With that caveat in place, we believe that there are active learning is generally both a welcome and effective addition to most small to medium sized courses.

As a general rule, we’d suggest that active learning activities are most effective when they:

- Promote learners’ thoughtful engagement with course material and the learning process

- Are accompanied by clear instructions and timely feedback (including any necessary correction)

- Are intentionally aligned with specific learning outcomes.

On this page we’ll highlight some of the evidence for the impact of active learning practices on lerarning in smaller classes, focusing on two low-risk, high-impact elements: involvement and student cooperation and collaboration.

Why Involvement Matters

The highly influential educational researcher Alexander “Sandy” Astin (now emeritus at UCLA) spent much of his research career trying to understand which variables are most likely to predict student success in college. Through the course of his research, he became convinced that what he called “student involvement” was central to undergraduate success. In a now famous article, first published in 1984, Astin defined involvement as “the amount of physical and psychological energy that the student devotes to the academic experience,” and argued that the amount of student learning and personal development that learners experience in an academic setting is directly correlated to the quality and quantity of the learner’s involvement. Astin believed that the consequences of his findings were fairly clear: in order for a particular curriculum to succeed, above all else it must “elicit sufficient student effort and investment of energy,” which meant that educators should “focus less on what they do and more on what the student does: how motivated the student is and how much time and energy the student devotes to the learning process.”

How Involvement Affects Learning

In the subsequent decades, Astin’s ideas have been deeply influenced several important developments in higher education, especially the development of what are often called learning communities (whether they be specialized dorms, first-year interest groups, mentoring relationships, service learning courses, language houses, honor societies, or even student orgs). Several thorough research studies have also confirmed many of Astin’s core findings: for example, one study of over 6,000 students in introductory physics courses at two nearby state schools whose sports teams also wear red and white and will remain unnamed found that students’ scored nearly twice as high on tests measuring their conceptual understanding in courses that used active learning methods than their peers in traditional courses. Other studies have found similar improved learning gains in courses that employ an active learning approach, and the researchers who have conducted these studies credit these gains to the nature of active engagement itself and not to any extra time spent studying the topic.

Why Cooperation and Collaboration Matter

All of us have experienced the dynamic, multiplying power of working in a healthy collaborative relationship. Cooperation is one of the most fundamental of human activities, the glue of our society, the engine of our deepest and most important relationships. Collaboration and cooperation can also be key drivers in successful active learning experiences, particularly in smaller courses. For more than 40 years, the brothers David and Roger Johnson (both long-time faculty members in the Education department and founding directors of the Cooperative Learning Institute at the University of Minnesota), have studied cooperative learning techniques in the classroom and collected empirical evidence about the impact of cooperation and collaboration on student learning. To learn more about cooperative learning and some popular approaches to its use in the college classroom, we’d recommend this introduction written by two chemical engineering professors from North Carolina State for a symposium on active learning in the analytical sciences.

How Cooperation & Collaboration Affect Learning

The Johnsons’ findings are both convincing and compelling. In their book, Active Learning: Cooperation in the College Classroom, the Johnsons and their research collaborator Karl Smith reviewed nearly a century of research into cooperation and reported that cooperation improved learning outcomes in nearly every instance. In 1998, they published a short article in the journal Choice which summarized their views on cooperation and its impact individual student learning, and in 2009, they produced what was essentially a concise summary of their career work in Educational Researcher, both of which are well worth reading. They have described successful cooperative learning situations as possessing the following essential elements:

- Positive interdependence (each group member depends on and is accountable to others, providing a strong incentive to help and accept help from their peers)

- Individual accountability (each person in the group learns the material)

- Promotive interaction (group members help one another, share information, offer clarifying explanations)

- Social skills (group members must practice leadership, communication, compromise)

- Group processing (group members must regularly assess how well they are working together and make necessary adjustments)

The Johnsons and other researchers have found that when these elements are present in a cooperative learning setting, the gains in learning that students experience can be enormous. Cooperative learning doesn’t only impact academic achievement, either; it has repeatedly been shown to improve the quality of learners’ interpersonal interactions, their self-esteem, and their retention in schools or academic programs. As an added bonus, there is some evidence that collaboration is particularly effective for improving retention of traditionally underrepresented groups, which is a major point of concern at UW-Madison. For instance, one meta-analysis of the impact of small-group learning by Leonard Springer, Mary Elizabeth Stanne (educational consultants then based in Madison, and Minnesota, respectively) and Samuel Donovan (then a biology professor at Beloit College) found that small-group learning had a “significant and positive” effect on achievement, persistence, and attitudes among undergraduates, and that this positive impact was “significantly greater for groups composed primarily or exclusively of African American and Latinas/os compared with predominantly white and relatively heterogeneous groups.” They also attempted to determine the impact of the amount of time students spent working together on student learning outcomes and attitudes. They found that medium group time had the highest correlation with achievement-related effects, but that high amounts of group time had the strongest positive impact on students’ attitudes (to learn more about their criteria for group time or their specific findings, please refer to the study itself).

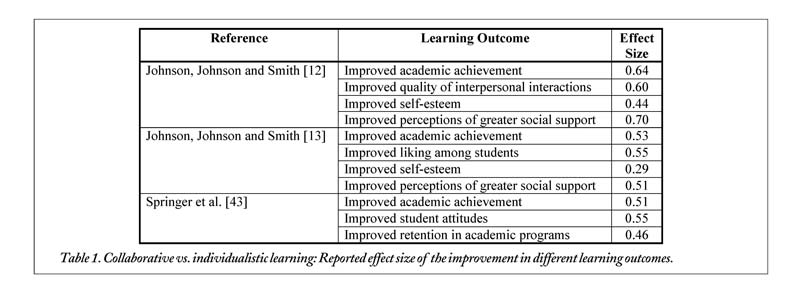

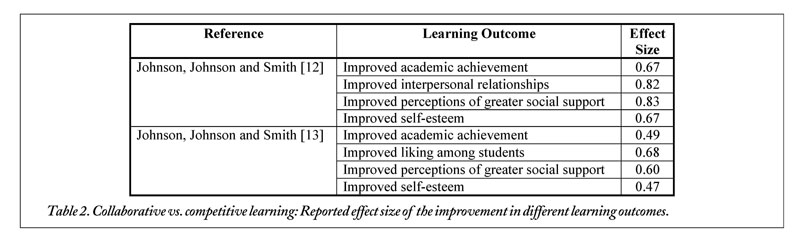

In a 2004 review of the evidence for active learning’s impact, engineering professor Michael Prince summarized the major meta-analyses of cooperative learning then extant and presented the following tables of cooperative learning’s effect size on various learning outcomes relative to individualistic or competitive approaches:

While effect size can be a difficult idea to grasp (especially if you’re not a stat-head who already works with it as a measure), Prince explains that with respect to academic achievement, even the effect documented in the lowest of the three studies cited (Springer et al.) would move a student from the 50th to the 70th percentile on an exam, and would be roughly equivalent with raising a student’s grade from 75 to 81.

After surveying the available evidence, Prince (an engineering professor) concludes, “Looking at what seems to work, there are significant positive effect sizes associated with placing students in small groups and using cooperative learning structures,” which I imagine is engineer-speak for “Holy cow, this active and cooperative learning stuff really seems to work!” If that’s indeed what he is saying, we agree!

Additional Reading:

We made reference to a few different studies on the impact of involvement and collaboration/cooperation on learning on this page. While each of the studies are linked to above, we’re collecting each of them here in one place for your convenience.

- Alexander Astin’s “Student Involvement: A Developmental Theory for Higher Education” (originally published 1984).

- Richard Hake’s “Interactive-engagement versus traditional methods; A six-thousand-student survey of mechanics test data for introductory physics courses” (1998). [Warning: the author is a physicist, and the article certainly reads that way. Not for the faint of heart.]

- Richard Felder and Rebecca Brent’s “Cooperative Learning” (2007)

- David Johnson, Roger Johnson, and Karl Smith’s “Cooperative Learning Returns to College” (1998).

- David and Roger Johnson’s “An Educational Psychology Success Story: Social Interdependence Theory and Cooperative Learning” (2009).

- Leonard Springer, Mary Elizabeth Stanne, and Samuel Donovan’s “Effects of Small-Group Learning on Undergraduates in Science, Mathematics, Engineering, and Technology: A Meta-Analysis” (1999).

- Michael Prince’s “Does Active Learning Work? A Review of the Research” (2004).

What’s Next?

In the next chapter we’ll look at active learning spaces on campus (and beyond!), and in the chapter which follows we’ll explore some specific practical ideas to increase student involvement and cooperative learning in the small- to mid-sized classes you teach or help support.

Media Attributions

- 3-modesB