Interactive Media

hypothes.is annotation layer

My dissertation is about participatory culture, and many of my chapters take up scenes in which characters in Victorian novels write in books. In this light, it is all the more appropriate for me to use the tools the web provides to enable others to write in my own text and to participate in the discussion. Hypothesis also allows participants to include hyperlinks and media artifacts in their posts.

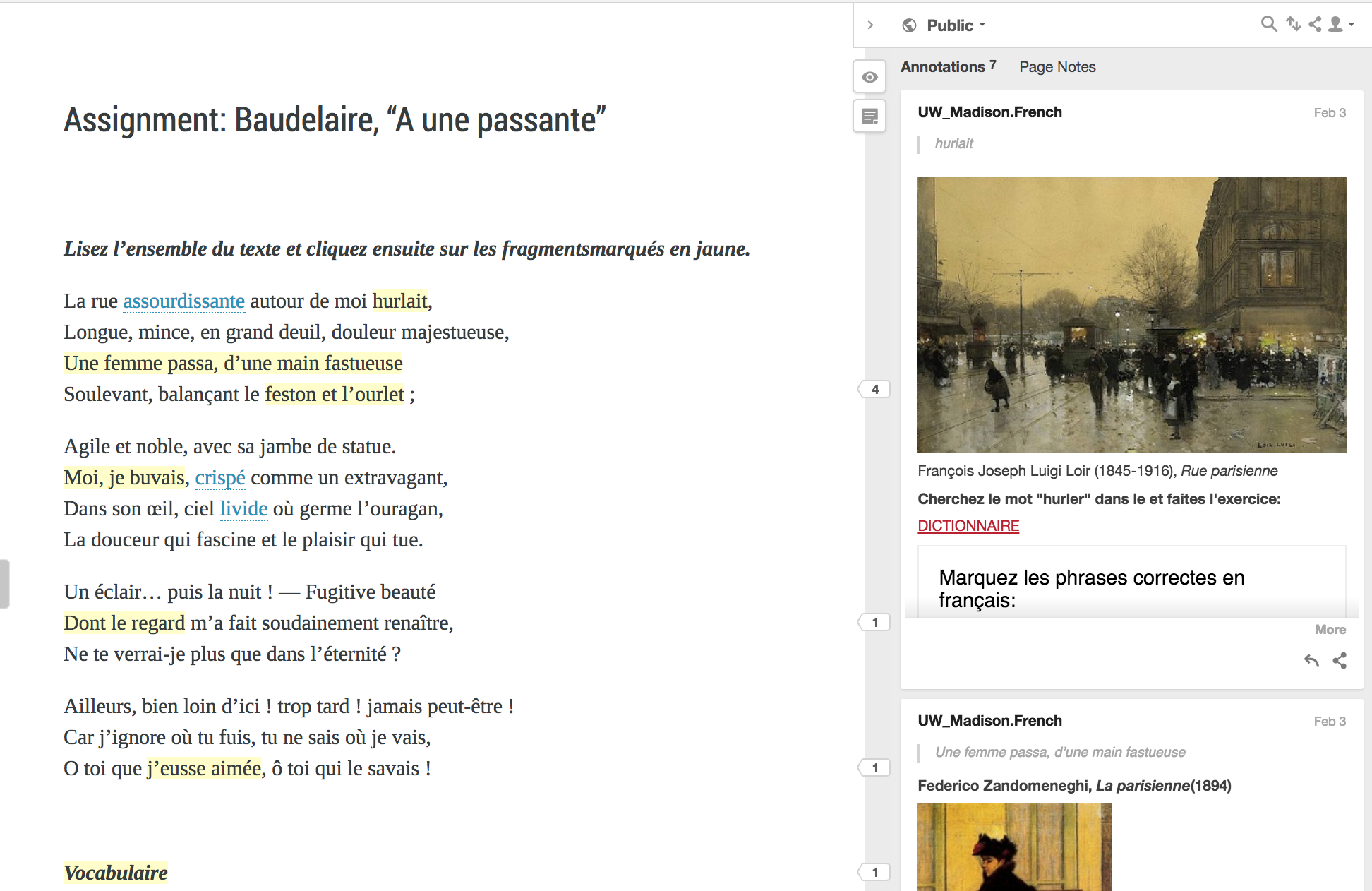

The image above is an example of a Pressbooks – Hypothesis integration I set up for the French department in my role as LSS OER Teaching Assistant. The Hypothesis annotation pane is on the right.

hypothes.is as an option for private committee engagement

I have created a private Hypothesis annotation group specifically for members of my academic community to take up (or take issue with!) aspects of my work if they wish to do so using this medium. (Clicking on the aforementioned link will provide you access and instructions for Hypothesis contributions.)

hypothes.is for future readers

After I have completed this project, I hope that others outside of my committee will engage in conversations with me in the margins of the public annotation layer. This is also a space I can use to provide links to new and relevant articles or other resources that emerge after my defense.

Primary Texts Embedded as Back Matter

All of the novels in my dissertation are in the public domain, and Project Gutenberg has a generous policy for reuse with modification. This means that I can include the full-text version of each novel in an appendix section of my dissertation.[1] This would enable me to invite reader engagement with my own approach to the text.

There are three reasons why I believe this would be useful:

1. An Invitation to Analysis

Literary scholars are sometimes accused of cherry-picking convenient lines from the text in order to construct their arguments. One way to address this allegation (and to actively work to avoid this practice) is to bring the primary sources closer to the audience. While citations are an implicit invitation to engage with a scholar’s quotations, it takes effort to obtain the correct edition of the text. It is, however, very easy to embed anchors into a Pressbooks text document and to generate a direct hyperlink to that portion of the text. From there, it’s a short click between close reading and context. For example:

2. An Invitation to Grangerize

Annotation, extra-illustration, and grangerization are seeing an enthusiastic renaissance thanks to resources like hypothes.is and Genius.com. Having an appended version of the original source text may allow participants to provide their own commentary on some of the sections of primary texts that are relevant to this project.

3. A Connection to the Classroom

This dissertation will include a section of teaching materials related to this project. For some of these activities–such as those that invite participants to extra-illustrate or analyze the text–an appended, easily-hyperlinked version of primary sources will be helpful to include in this text.

Image-Mapped Close Readings

Many of my primary sources are short enough to embed as images within my dissertation.[2] One form of interactive content that Pressbooks affords is the image hotspot activity, pictured below. For some of the most important periodical articles I discuss in my dissertation, I will include interactive images of the original article. This has two key advantages.

First, embedding these images into my dissertation would give readers a sense of the materiality of the original in a way that academic articles don’t often allow. Instead of simply reading a typed quotation on the screen, readers would be able to see a version of the article’s nineteenth-century layout.

The second application of these images relates to interpretation. Often, as researchers, we’re faced with some tough interpretive decisions while writing articles and chapters, as not all of the interesting or relevant close readings we could provide are necessary to include in paragraph form. Adding an image hotspot activity into the page would allow me to highlight points of interest in the primary text without letting these points of interest take over my close readings within the chapter discussion itself.

Potential Future Applications: Interaction-Tracking

In the future, it may be possible to enable this dissertation to tell a story about its own consumption. The team at LSS are currently working to make it possible for Pressbooks to record data about how people interact with interactive text elements when they access Pressbooks content from a Canvas course page. This means that an instructor working with this material could see how their students responded to the text and use these analytics to start a conversation with students about course reading practices. For example, they might pull up data on the average number of hypothes.is annotations that each member of the student audience read or replied to. Conversations about how current-day readers may be engaging with this text would raise questions associated with my dissertation’s content. This dissertation is about different types of textual interaction and modification and the way that people understood these acts. It would be interesting to invite my text’s audience to reflect on patterns of engagement with this text in the present day.

Another more public way to achieve this kind of self-reflexivity might be to set up a Google Analytics page for this Pressbook and see whether it is possible to embed the real-time results into a page in the back matter of this project.

Broader Discussion Space (Shared)

You are welcome to comment on this text using the annotation sidebar to the right of this page. By default, this document requires viewers to log in with a UW-Madison NetID. If nothing appears in the iframe window below this text, try navigating to the UW Google Suite login page, logging in to your Google drive there, and then refreshing this Resource Guide page. If you would like to access this page in a larger frame, this link will take you directly to the Google document below.

If you would prefer to access this page from a personal Gmail address, please email me and I will add you to the Team Drive folder that contains this file. From there, you’ll be able to see the Google Doc page below whenever you’re looking at this Pressbook while logged in to your Gmail account.

Back to “Dissertation Components” menu

- Why not simply include hyperlinks to the Gutenberg pages for the text, you may be asking? One reason is that I don't have control over the versions included in Gutenberg's archive and do not want to lose content if Gutenberg changes its files or text locations. Another reason is that including a copy of the text in my project allows me to create direct hyperlinks to quotes within the text, something that is not possible for me to do with another website. ↵

- In order to include these article images in my dissertation, I will need to locate (or produce) images of this content that would allow me to distribute the images as an open educational resource. ↵