Geography/Environmental Studies 339

Voluntary Emission Reductions: Paris and Beyond

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to explain:

- The basic architecture of the Paris Agreement;

- Strengths and weaknesses of the Paris Agreement; and

- Looking ahead: what to expect in the future.

The Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement was designed and agreed upon at COP21 in Paris in 2015 by nearly every nation. It is a legally-binding climate change mitigation treaty designed to be the successor to the Kyoto Protocol. To date, 195 countries have signed the Agreement and 187 Parties (of 197 Parties to the Convention) have ratified it. This represents 97% of global emissions. The only significant emitters which are not Parties to the Agreement are Iran and Turkey (But see more below on the United States’ stated intention to withdraw from the Agreement).

In order for the Agreement to formally come into force, at least 55 countries accounting in total for at least 55% of global greenhouse gas emissions had to ratify the treaty. This occurred in Oct of 2016 when 74 countries–including the US, the EU, India, and China–ratified the deal. The Agreement then formally came into force on November 4, 2016.

The broad goals of the Agreement are:

- to keep global average temperature rise well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-Industrial levels while pursuing efforts to limit the temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius;

- to provide a transparent framework for countries to set, monitor, verify, and publicly report on their emissions-reduction targets;

- and to strengthen developing countries’ ability to mitigate and adapt to climate change impacts by setting up a fund through which developed countries can channel money to developing countries for climate change mitigation and adaptation purposes.

How Does the Agreement Aim to Achieve These Goals?

For COP21, countries were asked to develop statements of “intended nationally determined contributions” (INDCs) which represent each country’s individual commitments (a) to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (a mitigation strategy) and/or (b) to reduce their vulnerability to climate change (an adaptation strategy). In contrast to the Kyoto Protocol, these self-determined country-specific contributions formed the basis for the Paris Agreement.

Once a country formally ratified the Agreement, the country’s “intended nationally determined contributions” were replaced by nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to ‘the Agreement. Ratifying countries are legally required by the Agreement to set, monitor, verify, and publicly report on their NDCs every five years. However, unlike the Kyoto Protocol, there are no legal requirements regarding how or by how much countries must reduce their emissions, and there are no financial penalties for not meeting their NDCs. Rather, the Agreement relies more on the enhanced transparency of the framework to foster a sense of global peer pressure and to make it easier to track which countries are setting and meeting ambitious goals, and which are not. One result of this approach, however, is that countries’ NDCs vary greatly both in scope and ambition.

With respect to mitigation, these commitments are highly varied and are normally stated as a reduction target:

- Commitments to reduce aggregate greenhouse gas emissions.

- Commitments to reduce the energy intensity (energy use per unit of GDP) or emissions intensity of its economy (GHG emissions per unit of GDP)

These commitments are seen to be met by achieving a certain percentage relative to a specified baseline, such as:

- The value of the target (aggregate emissions or fossil fuel intensity) in year X.

- The projected value of the target by achievement year based on a “business as usual” (BAU) scenario.

to be achieved by a certain year or range of years… with certain conditionalities (normally funding from industrialized countries)

Follow this link to open the World Resources Institute’s page (in a separate window) that tracks these commitments by country. To answer the following questions, enter the country name (India, China, United States or European Union) in the search box:

And select ‘NDC-Overview’ to read the summary of its emission reduction commitment.

The stated overall goal of the Paris Agreement is to keep global temperature increases well below 2 degrees C and closer to 1.5 degrees C. A number of commentators have made the point that even if these voluntary emission reductions were met within the stated time frames, global temperature increases would likely exceed 2 degrees C.

Climate Finance for Developing Countries in the Paris Agreement

You’ll recall that at COP17 in 2011 Parties to the UNFCCC agreed to establish a Green Climate Fund (GCF) that would provide US$100 billion per year to help poor countries adapt to climate change; however, developed country Parties have yet to achieve this level of funding. In the first round of funding for the GCF in 2014, 44 countries–including 23 traditional contributors, 12 other developed countries, and nine developing countries– pledged a cumulative total of US$10.3 billion to the Fund; however, parts of the pledged amount have yet to be transferred to the GCF.

The Paris Agreement upholds the acknowledgement, first made in the UNFCCC, that countries have significantly different capacities to prevent and adapt to the consequences of climate change. In Article 9, the Paris Agreement stipulates that developed country Parties must provide financial resources to the GCF to help developing country Parties with both mitigation and adaptation. Specifically, the Agreement requires developed country Parties to biennially provide transparent information on how (i.e. grants, loans, etc.) and how much funding they are currently pledging to developing country Parties (through the GCF) to assist with their climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies, and how much they expect to provide in the near future.

Beyond this requirement for transparency, the Paris Agreement also contains language that strongly urges but does not require developed country Parties to increase their level of financial support in order to achieve the goal of jointly providing USD$100 billion annually to developing countries by 2020 for mitigation and adaptation. It also states that that prior to 2025, country Parties must set a new collective target goal that starts at no less than USD 100 billion per year. Finally, the Agreement also highlights the acute need of countries that are particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change and have significant capacity constraints, like the least developed countries and small island developing States.

For those of you interested, you can see the status of countries’ pledges to the Green Climate Fund by following this link to the World Resource Institute’s Green Climate Fund Contributions Calculator.

U.S. announces intention to withdraw from Paris Accord

On June 1, 2017, U.S. President Trump announced his intention to withdraw from the Paris Climate Accord:

“As president, I can put no other consideration before the wellbeing of American citizens. The Paris climate accord is simply the latest example of Washington entering into an agreement that disadvantages the United State to the exclusive benefit of other countries, leaving American workers – who I love – and taxpayers to absorb the cost in terms of lost jobs, lower wages, shuttered factories, and vastly diminished economic production

For example, under the agreement, China will be able to increase these emissions by a staggering number of years – 13. They can do whatever they want for 13 years. Not us. India makes its participation contingent on receiving billions and billions and billions of dollars in foreign aid from developed countries. There are many other examples. But the bottom line is that the Paris accord is very unfair, at the highest level, to the United States.”

— Statement by President Trump on the Paris Climate Accord. The White House. Office of the Press Secretary. Rose Garden. June 01, 2017.

On Nov 4 2019, the United States made President Trump’s intention official: the U.S. notified the UNFCCC of its decision to withdraw from the Agreement. Per the Agreement’s terms outlining the process for withdrawal, the agreement must be in force for three years before any country can formally announce its intention to withdraw, which is why the U.S. had to wait until Nov 2019 to announce its withdrawal intentions. Then, the agreement stipulates that a country must wait a year after formally announcing its withdrawal intention before it can actually exit the Agreement. On Nov. 4, 2020, one day after President Trump lost his re-election bid, the U.S.’s exit from the Paris Agreement took effect. However, only hours after taking the oath of office, President Joe Biden announced the U.S. would rejoin the Paris Agreement, and this took effect 30 days later (on 2/19/21). The Biden administration must now get a divided Congress to pass legislation tho put the U.S. back on track to meet its commitments.

In the period between President’s Trump announcement to withdraw the U.S. from the Agreement and the country’s formal exit in 2020, the U.S. was required to continue participating in the COP meetings and climate negotiations. However, it did so in a grandstanding fashion. For example, at the 2018 COP 24 in Katowice, Poland, the United States (along with Australia) convened a panel extolling the merits of fossil fuel energy–particularly coal–that elicited protests (see photo). Moreover, the United States, along with Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait were able to water down the COP24 response to the IPCC’s special report about the impacts of a 1.5 degree C increase in global mean temperature that was elicited by the Paris Agreement itself and released approximately two months before COP24.

Despite the lack of support for the Paris Agreement by President Trump’s administration during 2017-2020, there were significant actions taken by local and state governments and private companies in the U.S. to reduce greenhouse gas emissions during this period. These actions are covered in the chapter on energy policy, but there are some estimates that these actions have advanced us significantly toward our Paris Agreement commitments. For those of you who are interested, a 2018 report making this argument by the climate action committee called America’s Pledge on Climate can be accessed through this link.

COP25 and Ambitious Targets

The most recent annual UN climate conference, COP25, took place in December 2019 in Madrid, Spain. COP25 was intended to be a stepping stone towards the next climate conference, in which countries will set new NDCs and funding commitments (the COP26 conference in Glasgow was re-scheduled for Nov 2021 due to to the COVID-19 pandemic).

COP25 took place after several reports confirmed that Party countries’ pledges to reduce emissions are insufficient if we want to avoid a 3.2 degrees Celsius rise in global temperature by 2100, more than double the ambitious 1.5 degrees Celsius goal of the Paris Agreement. Notably, a massive protest march took place in the middle of COP25 to call attention to this gap between current emissions reduction progress and the Agreement target goals to limit warning. Internationally renowned climate activist Greta Thunberg joined the protest march after her symbolic transatlantic journey by sailboat to participate in the protest against climate inaction.

Because country Parties’ NDCs are currently vastly insufficient, countries at COP25 attempted to agree on a paragraph of text that would call for greater ambition from all country Parties when setting the next NDC targets. According to the Agreement’s terms, NDCs must be set every five years and each successive NDC is supposed to “represent a progression” and “reflect [each country’s’] highest possible ambition.” However, many countries used their original INDCS–many of which go through 2030–to set their five-year NDC target. As a result, some countries have stated that they will simply be “re-communicating” the commitments they made in their INDCs, as opposed to setting new, more ambitious NDCs. To date, according to the World Resource Institute’s NDC tracker 103 countries, representing only 38.4% of global emissions, have stated they intend to enhance the mitigation ambition in their NDCs by COP26 (2021). Only one of these 103 countries–China– is a high emitter, and many are small and vulnerable developing nations.

Additionally, country Parties at COP25 failed to come to a consensus about what the word “ambition” should mean, with some–particularly developed countries– interpreting “ambition” more narrowly as a means to increase emissions reductions efforts after 2020, and others–especially India and other developing countries–arguing for a broader interpretation of “ambition” that would include increases to pledged climate finance and efforts to strengthen adaptation and capacity in poorer countries. The latter pointed to the failure of many developed countries to fulfill their pre-2020 NDC pledges and thus posing a threat to the integrity of the Paris Agreement and to any chance of thwarting global warming. The lack of support from the United States has complicated and slowed the commitments made by others.

At the close of COP25, the final agreed upon text ended up much weaker than first proposed. The text calls attention to the gap between current ambition and the Agreement’s global temperature goals and urges parties to consider the gap when “[re]communicat[ing]” or “updat[ing]” their NDCs. It also calls for “round tables” on ambition at COP26 and COP27.

Voluntary Commitments Made by Non-State Actors

Up and to now we have studied international climate agreements tied to a common set of GHG reductions for ratifiers (Kyoto Protocol) or varied voluntary commitments by ratifiers (Paris Agreement). While the Paris Agreement remains active, commitments and progress toward meeting these commitments have fallen short. In addition, the United States, the second largest emitter of GHG has entered, exited, entered, and exited the Paris Agreement which has not only slowed GHG emission reductions in the United States but has shaken the resolve of parties to the Paris Agreement. In the first few months of Donald Trump’s second term (2025), federal support for climate change mitigation was largely rolled back. The United States officially served notice of its intention to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, for a second time, on January 20th, 2025.

Federally supported wind farms were halted at the proposal and construction stages; much of Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which provided significant funding for renewable energy development was dissolved and any un-allocated funds frozen; and a new leasing plan for oil/gas wells and federal support for coal energy were announced.

But are voluntary commitments to reduce GHG emissions the only option? To meet their NDCs, national governments can create policies and make investments to reduce but they have always been dependent on reductions by local governments (e.g. cities, counties, states), individuals, and private companies. If a federal government is not actively pursuing GHG reductions, could these other actors make their own voluntary commitments and move to achieve them? The short answer is yes. Cities, companies and utilities around the world have pledged to reduce GHG emissions. Similar to Paris Agreement NDCs, these pledges take different forms with significant variation among pledging institutions to achieve or move toward their stated goals. Given the lack of federal commitment, and emissions responsibility, no where else in the world are such pledges as important than in the United States. This section describes:

- Voluntary commitments to reduce GHG emissions made by the largest cities, corporations and utilities in the U.S.

- What their commitments represent in terms of overall potential national GHG emissions reductions, and

- The progress made to reach these commitments so far.

What does “Net Zero” mean?

Net Zero means a balance between the amount of GHG gases emitted into the atmosphere and the amount removed. This can be achieved in many different ways. The most straightforward but difficult way is to switch all consumed energy to that produced through non-fossil fuel sources (solar, wind, hydroelectric, geothermal, nuclear etc.) It can also involve continued reliance on fossil fuels along with purchase of carbon offsets/credits to remove GHG emissions elsewhere. References to net zero are often made and should be scrutinized since some may, after reading the fine print, only be for a single part of an institution’s purview or only is achieved by purchasing credits that are produced elsewhere. Please note that the terms “net zero,” “decarbonization,” “zero emissions,” “clean energy,” “carbon neutral,” “climate neutral” and “climate friendly,” are defined differently depending on the context, and are sometimes used interchangeably. They all might include fossil fuels or carbon offsets/credits. Terms which generally do not include fossil fuels or offsets/credits include “fossil-fuel free,” “zero-carbon,” “carbon-free,” and “direct reductions.” See the “Net Zero Timeline” and more info here.

Cities

In the U.S., urban regions account for around 70% of GHG emissions, but facilities/operations owned by cities themselves only account for roughly 1-5% of those emissions. Between 2018-2023, 157 U.S. cities published Climate Action Plans (CAPs) that include GHG accounting inventories, which form a necessary baseline to track reductions, and specific reduction targets. Similar to Paris NDCs, there is a large variation in reduction targets, and their timelines. Many of these plans are limited to municipal operations, which represent a very small fraction of a city’s emissions, but a number of them have been updated recently with reduction goals for the commercial and residential sectors. Goals that address high-polluting industries have been slower to develop.

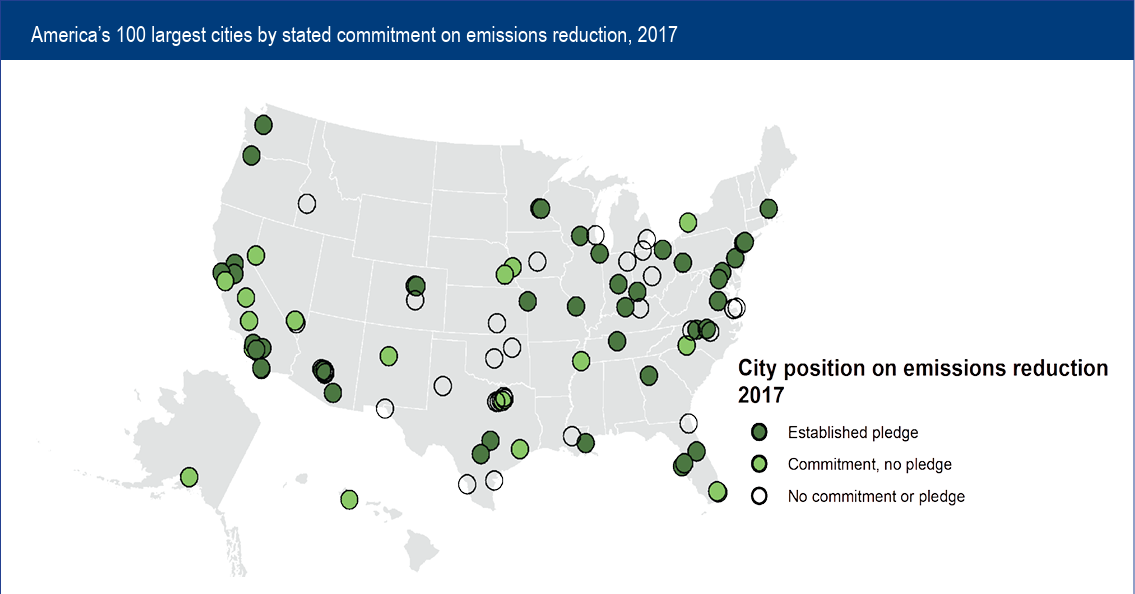

According to Brookings Institute, of the 100 most populous cities in the U.S., about half (45, “Established pledge” on map below) have established GHG reduction targets and corresponding inventories necessary to track progress. 22 have committed to reducing emissions but have not established targets or completed a baseline inventory upon which to base a reduction plan (“Commitment, no pledge” on map). The 45 established pledges, if met, would reduce U.S. GHG emissions by roughly 6% of what total emissions were in 2017.

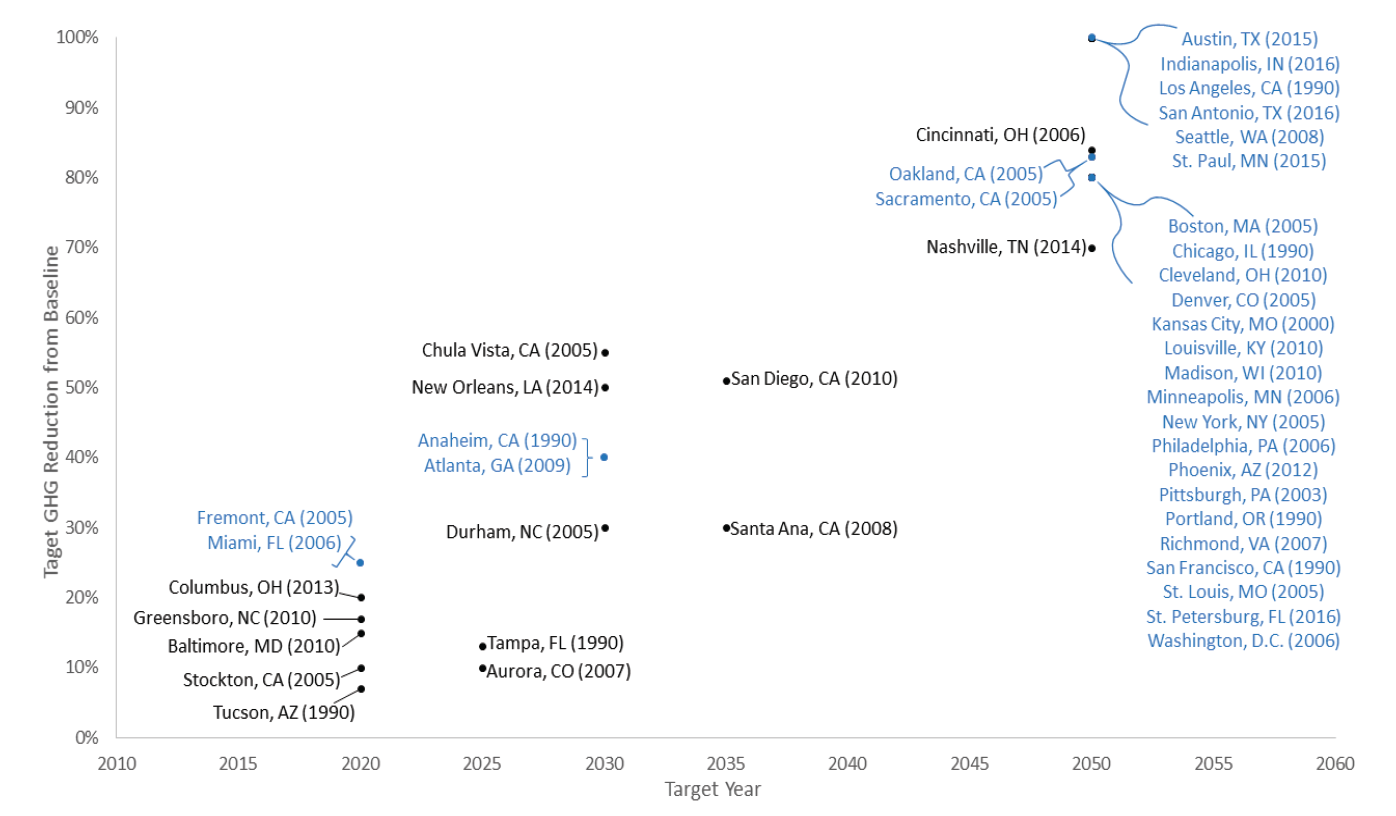

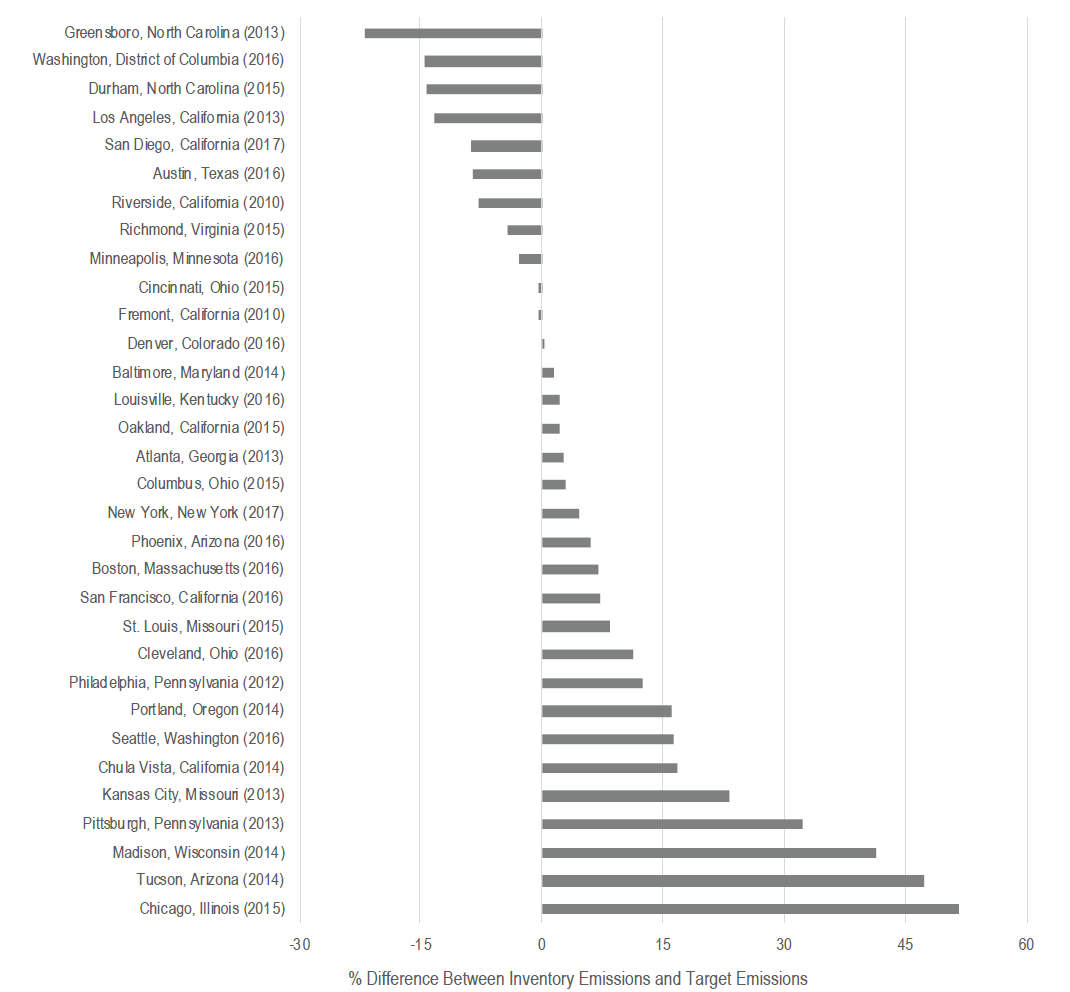

Similar to Paris Agreement national targets, each city plan differs in timeline, specific emissions reduction targets, amount of detail, accounting/reporting mechanisms, and enforcement strategies. Only 54% of plans explicitly aim to achieve “net-zero emissions by 2050.” Some plans end at 20% or 50% in 2020, 2030 or 2035. Only one-third have detailed benchmarks and reporting. The Figure below shows the final targeted percent reduction in emissions and the final year by which the reduction should be fully achieved. The values in parentheses next to the city names correspond to the baseline year of their CAP. Values in blue represent cities with the same reduction target and year.

If you would like to investigate a particular city more in depth, this page shows the level of specificity of the plans of the largest U.S. cities, and includes links to the plans themselves.

About two-thirds of cities are currently behind their targeted emission levels. On average, cities will still need to reduce their annual emissions by 64% by 2050 in order to reach their ultimate reduction targets. The next figure displays the progress of cities towards their goals as the difference between their most recent inventory and the targeted emission level in the year of the inventory. A number of factors may impact a city’s progress towards its stated goals. First is the ambition of the target in the first place. Some targets are easier to achieve than others. As mentioned above, the targets of some cities, like Greensboro N.C., only seek to reduce GHG emissions of city operations while others like Chicago and Madison seek to reduce city-wide GHG emissions. Moreover, as shown in the previous figure, city commitments vary widely in terms of the timeline and the level of reduction commitments. A city may lay out a vision in a CAP but face political hurdles in implementing the plan. In addition, many factors affecting the city-wide GHG emissions are not within the control of city government. A city government can create policies and plans to spur GHG emission reductions but reductions only occur through actions by electric utilities, companies, and residents of the city. A city’s growth will increase its energy demand (particularly AI data centers) and complicate the shift from a fossil fuel energy supply. Federal and state policies and programs will also help or hinder a city reaching its reduction target.

Despite its seemingly slower progress towards its reduction goal, Chicago shows promise in reducing its GHG emissions. Please read this short article describing its efforts to obtain renewable energy, then answer the following question.

Companies

Companies emit greenhouse gases through fossil fuel consumption in their operations to provide goods and services. In the United States, businesses consume around 40% of all energy used in the form of fossil fuels for transportation, heating and industrial processes. Thus, the business sector represents an important source of GHG.

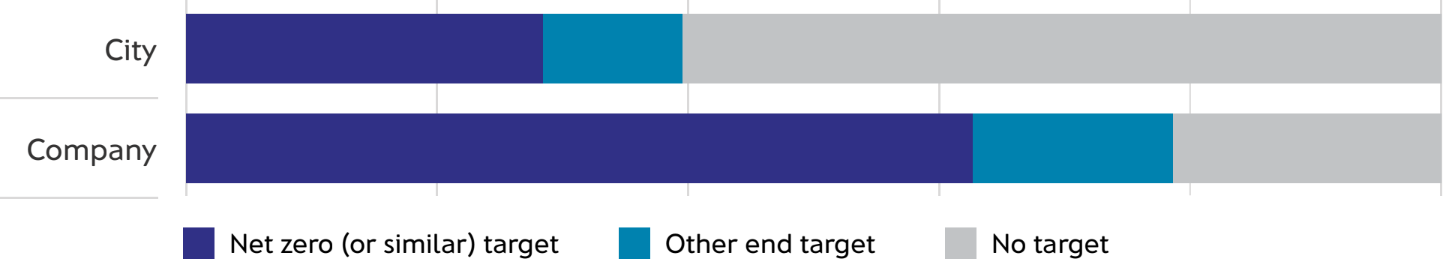

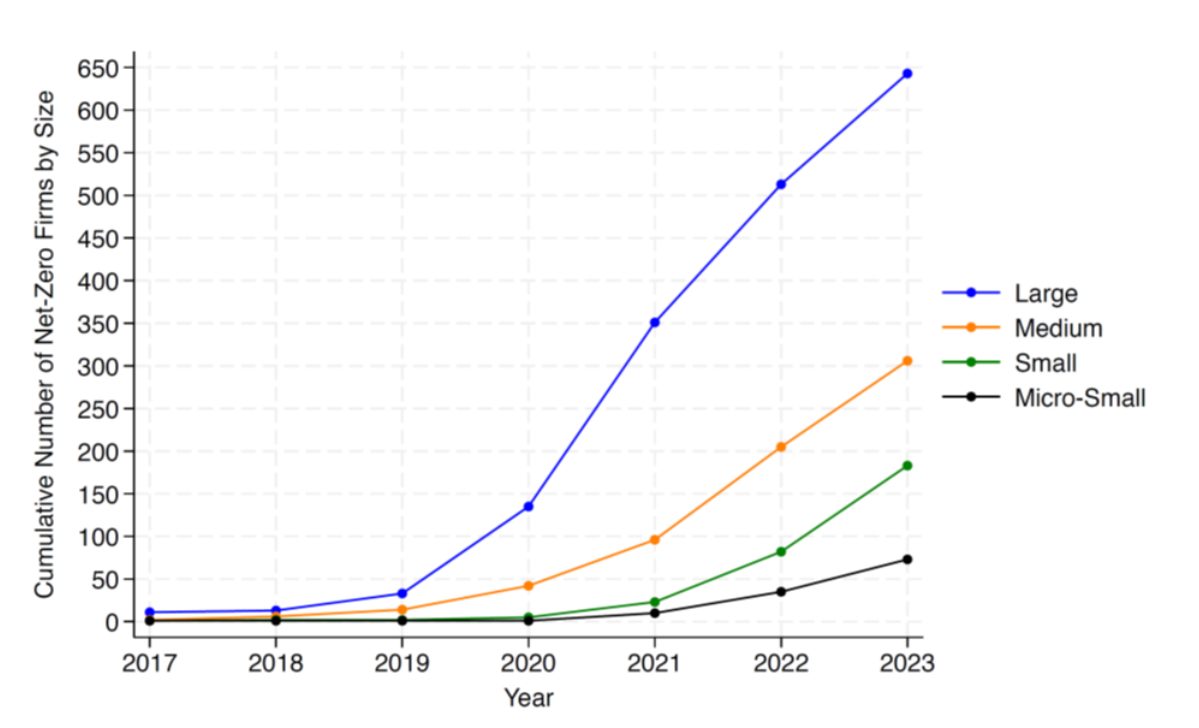

Among the world’s largest 2,000 companies, it has been estimated that more than half have set reduction targets. These commitments are mostly voluntary, though European countries and the U.S. state of California are introducing mandatory reporting standards, for companies over a certain size. Besides these regulations, companies have a number of incentives for disclosing emissions and announcing targets publicly including public relations, responding to stockholders, being ahead of government regulations and staying competitive. Commitments have increased significantly since 2019 and are more common among large companies who hold influence over markets and policies, and have enough assets to make bold targets with confidence. They also are more likely to have operations within government jurisdictions requiring them to reduce emissions. This figure shows the cumulative number of firms having made a Net Zero commitment by firm size [Note that firm size is measured by assets: “Large” ($10 billion or more), “Medium” ($2 billion to $10 billion), “Small” ($250 million to $2 billion), and “Micro-small” ($250 million or less).]

Commitments are typically expressed as net zero obligations although the transparency and clarity of obligations vary widely with some companies announcing plans with little of the specificity needed for implementation. A major uncertainty is the degree to which obligations are met through the purchase of carbon offsets/credits from emission reductions elsewhere to achieve neutrality. As will be discussed in a subsequent chapter, the carbon credit/offset market is plagued with poor monitoring leading to some skepticism about whether they represent real reductions.

Most corporate pledges have a short horizon, with close to 50% specifying a target date less than five years away. This reflects the risk adverse nature of companies as the political and economic benefits of GHG reductions can change rapidly with time. Actual commitments to reduce GHG emissions (not through offsets) vary widely with 70% of pledges committing to a total reduction that is less than 40% of base year emissions. Only 7% of companies in one sample pledged to completely decarbonize. Overall, 72% of companies with pledges are behind on their committed trajectories.

U.S. Companies Activity

Let us now get a bit more into the details of emission accounting by corporations. Corporations often buy electricity from utilities and materials and merchandise from suppliers. Reduction targets can be directed at a company’s direct operations as described above (Scope 1) but also its suppliers of electricity (Scope 2) and the operations of its suppliers (Scope 3). Companies vary in the degree to which their commitments address these different scopes. Commitments that include not only Scope 1 but also Scopes 2 or 3 are necessary for wider reductions in the economy. Now let’s explore some important factors within the commitments of companies in the U.S. through the site NetZeroTracker.

- Go to https://zerotracker.net/ and for “Country or Region” choose “United States of America” and for “Entity Type” choose “Companies. Then use the indicator box to answer the following question.

Electric Utilities

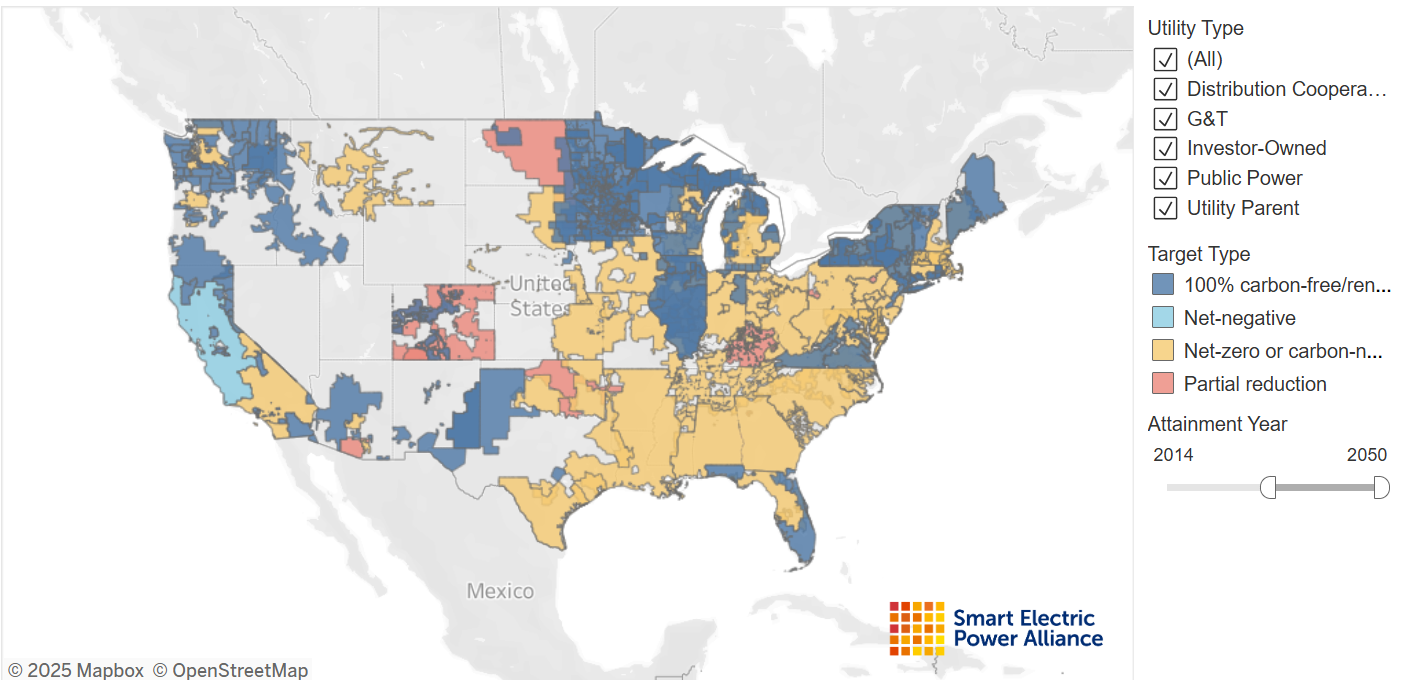

Electric utilities consume 34% of U.S. energy supply to produce electricity consumed by government, individuals, and companies. Utilities have a unique and pivotal role to play in the transition to renewable energy. As key energy providers, they have an inherent leadership position with connections to industries and politicians. As opposed to the entities outlined above, utilities have generally committed to the more ambitious Paris Agreement GHG emission reduction pathway, with 81% of US customer accounts now being served by a utility with a reduction target of 100% by 2050. Many of these plans are mandated by the states they operate in.

This map from Smart Electric Power Alliance shows utility reduction targets. Dark blue is “100% carbon-free/renewable energy” (no use of carbon credits/offsets), light blue “net-negative,” light orange “net-zero or carbon-neutral” and light red is a commitment to “partial reductions.” Many of these commitments are recent and their effectiveness has not yet been evaluated. There are both reasons for optimism, with some utilities on track to meet their targets, and reasons for concern with examples of utilities backsliding on their targets.

Large privately owned utility example: Xcel Energy

Xcel is an investor owned utility (IOU) serving parts of Colorado, Minnesota and 6 other states. In 2018, it was the first in the U.S. to announce it would deliver 100% clean, carbon-free electricity by 2050, with an interim target of 80% by 2030. According to Xcel, progress has been steady and they are on track to meet the first target: “Through 2024, we reduced emissions from electricity by 57%, a further 3% decrease from 2023. Our energy mix is also more than 50% carbon-free.” Xcel has closed down 25 coal units since 2007 with no worker layoffs.

Large public utility example: Public Renewable Power in New York

As a result of years of grassroots organizing, the Build Public Renewables Act was passed in New York State in 2023. It enables the New York Power Authority (NYPA), one of the nation’s largest publicly owned electricity providers to, every year, perform a review on whether NY electricity supply is on track to reach 70% renewables by 2030 and 100% by 2040, per state mandates. If it’s not, NYPA will step in to build enough to make up the gap. The law also introduced a program for low and moderate income residents to receive credits for clean energy produced by the utility and allocated $25 million each year to renewable energy job training, among other measures. Read more here.

RECs, PPAs and other forms of renewable energy procurement

A clear way to measure progress towards net-zero goals is by looking at energy procurement. Besides building on-site renewables, Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) and Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) are ways for cities and companies to fund and buy power directly from specific renewable sources. There are also “community solar” agreements, “green tariffs,” and other emerging forms of renewable energy transactions. While some are conducted over open-electricity markets, they are not indirect, like offsets/credits. They uphold the “additionality” principle that every power deal should add more renewable energy to the grid, as opposed to offsets which can’t make that guarantee.

They support investments and represent a contractual obligation to use renewables. In the U.S. in 2021, 155 local governments signed 290 renewable energy deals, 25% more cities and 55% more deals than the 2020 record. This adds to a total of 1,183 transactions by 723 local governments since 2015. Use this map to explore local government transactions. These transactions become even more crucial when looking at companies. Over 40% of all renewable energy being procured and built in the U.S. is through corporate PPAs and RECs, with companies like Google, Amazon and Microsoft purchasing the most.

Conclusion

“America’s climate-leading states, cities, Tribal nations, businesses, and institutions will not waver in our commitment to confronting the climate crisis, protecting our progress, and relentlessly pressing forward. No matter what, we’ll fight for the future Americans demand and deserve, where our communities, our health, our environment, and our economy all thrive. We will not turn back.“ – The Climate Mayors, a coalition of 350 city mayors from 46 U.S. states

Since 2019, there has been a large upswing of commitments made by cities, corporations, and companies to reduce GHG emissions. These commitments have synergistic effects. The fulfilling of commitments by utilities will allow cities and companies who consume the electricity produced by utilities to more easily reach their commitments. Likewise, city and corporate REC/PPAs reduce the uncertainty surrounding renewable investments for utilities. As contributors to GHG emissions in cities, the fulfilling of corporate commitments contribute to the carbon balance sheets of cities where they or their suppliers operate.

These commitments are significant and if fulfilled will help the United States mitigate climate change within its borders despite the lack of federal support. Such actions do not need full federal support. Still, the posture of the federal government does reduce the general pressure on these entities to fulfill their obligations. Thus there may be backsliding. The changing regulatory and investment support surrounding renewables and fossil fuels can also create barriers to green energy transitions. It is important to recognize though that pressure can come from voters and consumers and the political arenas where such pressure can more successively be applied is not in Washington D.C. but at the local level (city hearings, public utility commission meetings, local elections).