Part 1: Essentials of Course Design

Design for Learning

Humans have a strong proclivity for categorizing, cataloging, and classifying. This is how we learn. And we do it for everything: “This is a dog, that is cat. This is a quadratic equation, that is a linear equation.”

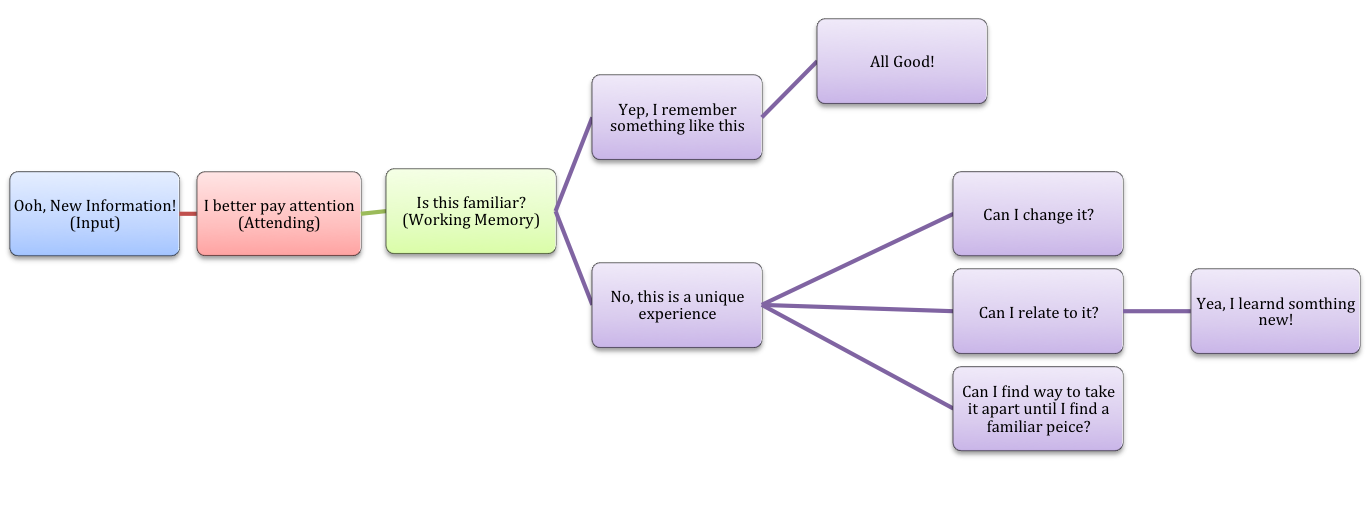

When our minds encounter a new piece of information, we make sense of it by engaging in categorizing, cataloging, and classifying, through a number of cognitive tasks. Let’s take a look at a simplified version of the cognitive tasks our minds engage in when faced with a new piece of information.

This pathway is an automatic process over which instructors and students have little control. We may be unable to manipulate the functions, but we control the input and can heavily influence how students interact with and categorize it.

Teaching in higher education has traditionally has focused on gathering as much information – or inputs – as possible, and distributing that content to students via lectures or textbooks. We then expect that students will somehow learn something from this input and be able to output that information in an exam. In so doing, we fail to take into consideration what is happening in the students’ minds during class (the cognitive process) or what we as instructors can do to help students learn something new.

It is therefore essential that we think deliberately about how students learn before we finalize course content (input). It matters little if your course content (the input you provide students) is cutting edge, if you fail to provide that content in such a way that students are able to attend to that input, categorize it, and relate it to their working memory, interests and goals.

Keep this flowchart in mind as you plan and build your course.Your responsibility as an instructor does not end at the beginning of this flowchart but at its conclusion, when a student can truthfully say “Yea, I’ve learned something new!”

The Basics of Course Design to Promote Effective Learning

Understanding how learning happens is an important consideration in course design and delivery. It is, obviously, only part of the design process. We recommend designing your course with these three concepts in mind:

- Content: Not only do you need to plan for the new content you will be teaching, it is important to anticipate prior knowledge and prerequisites, and understand the roll that content plays in building students’ up to the next level of knowledge. Helping students make connections to previously learned material helps them learn more effectively and in a deeper way.

- Cognitive structure: Information needs to be organized hierarchically. It should be organized according to discipline standards, but likewise in terms of the hierarchical way our minds build knowledge. The way content is organized and delivered will impact how your students connect that information to other knowledge.

- Constraints: Consider both the physical and digital environment as you organize content and cognitive tasks. What content is best delivered online? What content is best delivered in a face-to-face environment? Be willing to reevaluate if an idea fails and always work to keep technology in the ‘background’ — mastering content learning objectives should be the focus of each activity, not mastering the technology.

Backward Design: A framework for instructional design

One method for helping you navigate the course design based on the concepts above is Backward Design. Backward Design is a very large topic; visit the Appendix for in-depth resources. However, the following will help you become more familiar with Backward Design and how to begin to implement it in your own course design.

Design With the End in Mind: Backward Design begins by answering the all-important question: “What do I want students to know (and/or do) after taking this course? Defining what you want your students to be able to do after they finish your course (your course objectives) allows you to work backwards to identify how to help students progress to those end goals and choose what lectures, assessments, and activities are appropriate for the task.

Learning Outcomes/Objectives: A more formal and best practice method for articulating learning goals is writing Learning Outcomes.[1] Learning Outcomes are the knowledge and skills the students have after finishing the course. They should be presented to students in a structured and predictable manner. When writing learning outcomes an instructor may use the language, “The learner will be able to . . . ”

Pay attention to the verbs in each of these examples.

- “The learner will be able to apply_______ to__________.”

- “The learner will be able to define _________.”

- “The learner will be able to demonstrate ___________.”

Learning Outcomes require an “action” verb, or a verb that can be measured. Note the difference between:

“The learner will understand how to_______.” vs. “The learner will illustrate how to_______.”

It is hard to know when somebody understands something unless they are able to show or apply the knowledge. A learning objective using an action verb inherently lends itself to designing an activity or an assessment in which an instructor can measure understanding. Click here for a helpful list of Action Verbs you can use when designing Learning Outcomes.

Mapping your course: Once you have defined your Learning Outcomes you can begin to map out your course. Mapping out your course helps you determine:

- What do I want my students to know or be able to do?

- What method and activities will I use to help students achieve each outcome?

- In what order will students engage with each outcome?

- How will I know (assess) that they have met a learning outcome?

Implementing your course map in D2L

Mapping your course is even more important if you are planning to deliver content and facilitate activities online. It will help you set up your course structure and help you create an environment that helps students understand:

- What you want them to do

- When and how you want them to do it

- How they will access the material or activity

D2L structures it’s online environment with Modules. It might be helpful to think of a module as a course Unit. Units, or Modules, can be built around each Learning Outcome, but more often than not, they are built around a large theme or concept. That theme or concept might touch on more than one Learning Outcome, and each Learning Outcomes can be associated with more than one theme.

Course Modules contain the instructional materials or activities you would like your students to access online. In D2L, these could be PDF’s or documents of readings, videos, Powerpoints, quizzes, discussions, or access to a Dropbox for turning in an assignment. A module might also include links to activities or readings elsewhere on the web.

For example, you may decide that for the first week of class you want the students to have an introduction to the material and concepts being taught in the class and to understand how those relate to the discipline as a whole.

Therefore, in Week One you might focus on two learning objectives: LO 1: “The learner will describe the relationship between this course and previous courses in the sequence to demonstrate their understanding of the discipline as a whole;” and LO 2: “The learner will provide definitions for discipline related terminology related to the course.” Of course, you will also need to take care of some course management like the syllabus and your expectations of how they will use the D2L site.

You module might end up containing:

- Welcome to the course (HTML Page)

- Syllabus (uploaded file)

- How to use our D2L site (screen cast video)

- Assignment: In a page or less please consider the courses your taken in this discipline. What main concepts or ideas have you learned in this sequence? How do you anticipate this course will contribute to your understanding and skills? (Dropbox)

- Reading: Important concepts of ______ (uploaded file)

- Assignment: Define the important concepts of _____ (Quiz)

Planning ahead by considering Content and Cognition will help you make the most of your D2L site. Keep this in mind as you work through other modules in this guide.

Resources

Nilson, Linda. Teaching at Its Best: A Research-Based Resource for College Instructors. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2010.

Tools for Great Teachers. “Team Collaboration & Planning: The Four Questions and Backwards Design.” http://www.toolsforgreatteachers.com/the-four-questions-and-backwards-design-plus-a-planning-tool.

- "Outcomes" and "objectives" are frequently used interchangeably. Curriculum specialists tend to use "outcomes" as the big, overarching goals within a class, and "objectives" as scaffolded tasks students must complete to meet an outcome. ↵