Geography/Environmental Studies 339

Divergent Energy Policies: U.S. and Abroad

Learning Objectives

After completing this lesson, you will understand:

- the link between energy policies and international climate commitments

- the rationale for government intervention in the energy sector

- the strengths and weaknesses of major types of energy policy options

- how carbon markets work

- the recent history of U.S. energy policy initiatives in response to climate change

- the contrasting approach taken by Germany (Energiewende)

- the range of policy initiatives being taken around the world to reduce greenhouse gas emissions

Connecting International Climate Agreements with Domestic Energy Policy

If the world takes climate change seriously, renewable energy alternatives need to be stimulated through policy. International climate agreements, such as the Kyoto Protocol and Paris Accord, ask countries to make commitments to achieve target goals around climate change mitigation, such as reducing GHG emissions. While meeting these commitments are supposed to be obligatory for countries that ratify the agreements, there are actually no legal mechanisms in place to enforce fulfillment. It is up to each country to pursue the renewable energy technology necessary to meet its goals, and to create domestic policy that implements this technology and reinforces these goals.

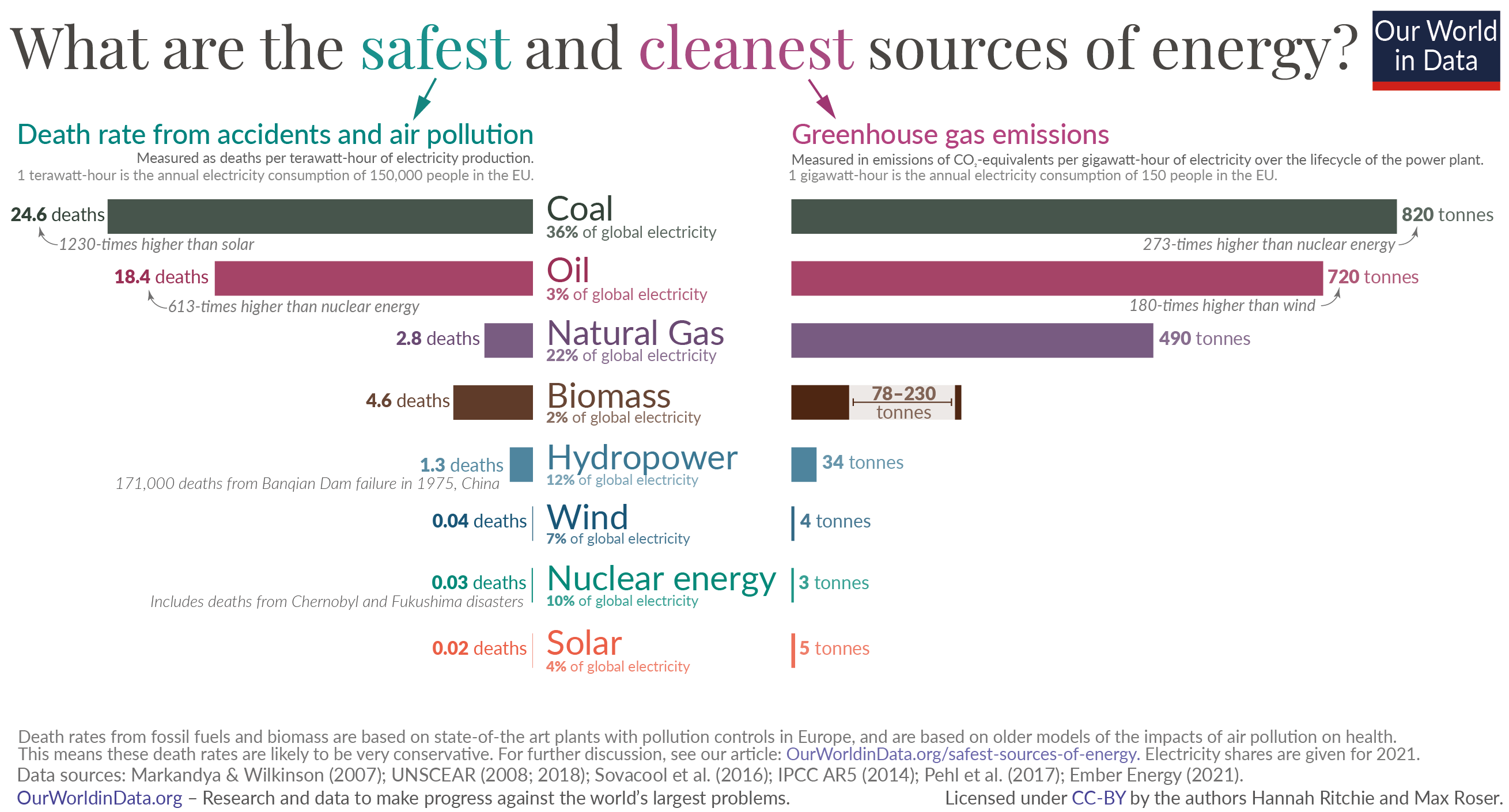

As we have learned, ratifiers of the Paris Accord have made pledges to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Most all of the opportunities to make such reductions are tied to reduced dependence on fossil fuels. Governments generally need to implement policies in order to reach these commitments. A role for government intervention to assure changes away from fossil fuels is that without such policies, the private sector is responding to energy prices that do not reflect the true cost of different energy sources. In other words, fossil fuel prices are lower than they would be if the full costs of their combustion was factored in. This is a widely-accepted reason for government involvement in the energy sector. The focus of this chapter is to investigate the form that such involvement should take.

When we speak of energy policy, we generally refer to policies enacted at the national and local levels within countries. While we have learned about international agreements that allow for emission reduction credits to move across international borders, the incentives to seek such credits are necessarily produced by national and local governments — not by the UNFCCC. Even international trading markets need to be supported by domestic policies of participating countries in order to be successful.

After a brief review of different policy options available to governments, we will compare the national energy policies of a few countries around the world, with a closer look at the United States and Germany. Both are highly industrialized countries but have shown quite different levels of government involvement in supporting a transition away from fossil fuels.

Different Energy Policy Options Available to Government

In very basic terms, government policies can support transitions away from fossil fuels through a combination of rule-based regulation and incentive-based efforts through subsidy of alternatives or increasing the cost of fossil fuels. It is important to recognize that any energy policy relies on some combination of these approaches. Moreover, incentive-based programs need regulations to establish new rules for the market or to introduce new markets into the private sector.

In this section, jump to:

Subsidies

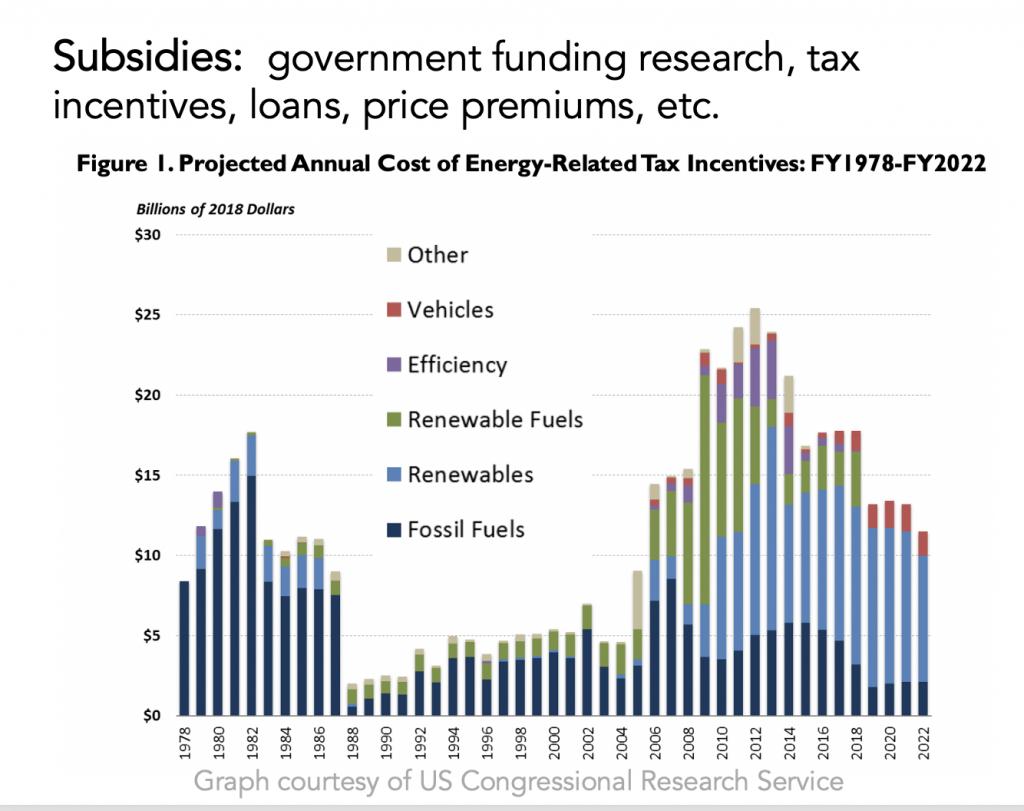

Government can help elicit changes in our energy supply through subsidies. Due in part to security concerns related to our energy supply and the strengths of fossil fuel lobbying efforts, the United States has a long history of supporting the fossil fuel industry. Historically, the fossil fuel sector has received approximately two-thirds of government subsidies since 1916. See “Subsidies” Figure below for data 1978-2018 plus projections through 2022. Note: these projections were made before Biden announced the American Jobs Plan. Also note, ‘renewable fuels’ refers to ethanol and biofuels.

Since 2006, subsidies directed at energy conservation and renewables have been added to those long directed at fossil fuels and nuclear power with the government estimating that renewable subsidies exceeded those supporting fossil fuels in 2016. Explore the dropdown menu below to learn more about subsidies.

Detractors of such subsidies argue that the government should not pick “winners” in the marketplace. Others argue the role of government subsidies for all large-scale technological developments has always existed and that subsidies can quickly stimulate both technology advances and technology adoption. For example, it has been persuasively argued that government subsidies have played an important role in the dramatic decline in costs for renewable energy systems since 2010.

Another policy approach is to increase the costs of using fossil fuels to better reflect their true costs as contributors to climate change as well as environmental and public health damages. There are two primary approaches to increasing these costs: through carbon markets and through a direct carbon tax.

Carbon Markets

Carbon markets are any trading system through which countries, companies, individuals, and other entities may buy or sell units of greenhouse-gas emissions (one tonne of carbon dioxide emissions or its equivalent) to meet either required or voluntary emissions limits. There are two primary types of carbon markets: emissions trading systems (commonly referred to as cap and trade) and carbon offsetting systems.

In cap and trade markets, companies trade emissions permits, allowing them to emit a certain amount of GHGs. The goal of these markets is to achieve an overall emission reduction goal at the least cost to the economy. Those emitters who can more easily (cheaply) reduce emissions, will tend to sell emission permits to those for whom it is more costly to reduce emissions.

In cap and trade markets, companies trade emissions permits, allowing them to emit a certain amount of GHGs. The goal of these markets is to achieve an overall emission reduction goal at the least cost to the economy. Those emitters who can more easily (cheaply) reduce emissions, will tend to sell emission permits to those for whom it is more costly to reduce emissions.

In carbon offset systems, companies trade carbon offsets, or units of reduced or sequestered GHG emissions. Through carbon offsets, companies can claim emission reductions by paying for reductions done elsewhere (presumably at lower cost than they can achieve within their own operations). Both systems operate under the theory that it doesn’t matter where the emissions are occurring, but rather that the accumulation of global emissions is limited overall.

Carbon Tax

A true taxation approach is what is most often favored by economists to reduce GHG emissions. The so-called “carbon tax” would be a tax on fossil fuel use. In the United States, efforts to legislate a carbon tax or cap-and-trade at the national level have continued to no avail, partly due to resistance from Republican legislators. There has however been an increase in bipartisan support within Congress and increased calls from the private sector for a carbon tax. At the state level, Washington State voted on a statewide carbon tax initiative in 2018 (it failed with 56% against).

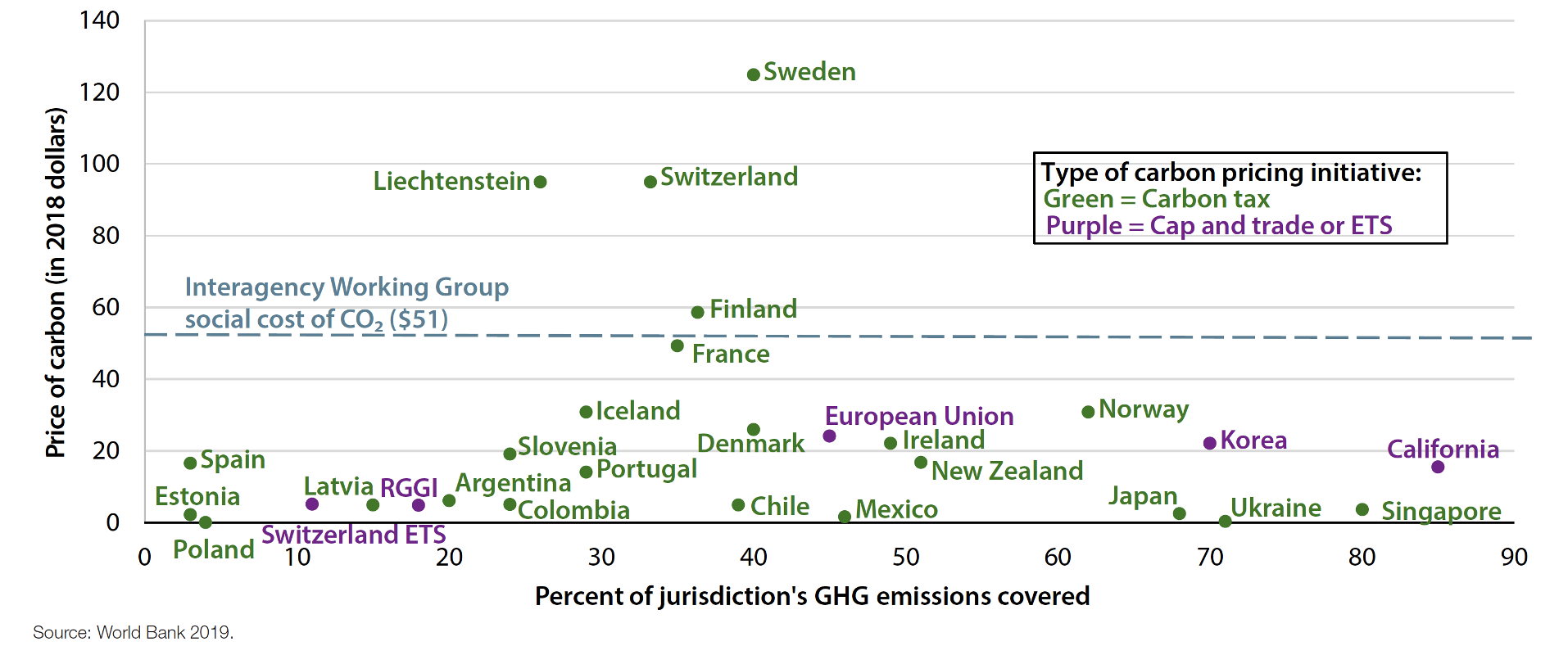

Carbon Pricing

The figure below shows 2019 data for countries, states and regions according to the type of carbon pricing initiative (carbon tax or cap and trade), the price of carbon (vertical axis) and % of jurisdiction’s GHG emissions covered). Despite the growing implementation of these programs, the majority of carbon prices are still below the estimated social cost of CO2 ($51 per ton of CO2equiv).

Restricting carbon emission allowances or raising a carbon tax is not simply an economic decision but also a political one. While the 2018 protests in France by the gillets jaunes (yellow vests) were motivated by a range of grievances, a major initiating factor was the introduction of fuel taxes by the government, which subsequently postponed these tax hikes as a result of the protests.

The U.S. has historically not pursued any plans to implement carbon pricing programs (either via cap-and-trade or carbon taxes). One argument against raising the price on carbon is the concern that this would unfairly affect the poor because they already pay a larger portion of their income for energy than do more affluent citizens. But several states (e.g. CA, PA, MA, and OR) are using emissions trading programs to meet climate goals over the next decade.

Regulation

As mentioned above, all programs that subsidize renewables or increase the price of fossil fuel use require some form of regulation. Rules need to be set for eligibilities for taxes and subsidies as well as to govern emission trading. Regulation can also be used in energy policy as the enactment of rules independent of these incentive-based programs such as taxes, subsidies, and government sponsored markets. For example, in the United States regulation was used heavily by Obama’s Administration. Responding to resistance by Congressional Republicans to new climate or energy policy legislation, the EPA, using its executive authority to implement the Clean Air Act, effectively passing new rules to reduce GHG emissions.

Click on the dropdown below to learn more about Obama’s actions and subsequent responses from the Trump and Biden Administration below:

This pattern of regulatory reforms and reversals points to the limitations of relying on rule changes based on reinterpretations of existing law (Clean Air Act).

U.S. Energy and Climate Policy

Comparison of National Energy & Climate Policies

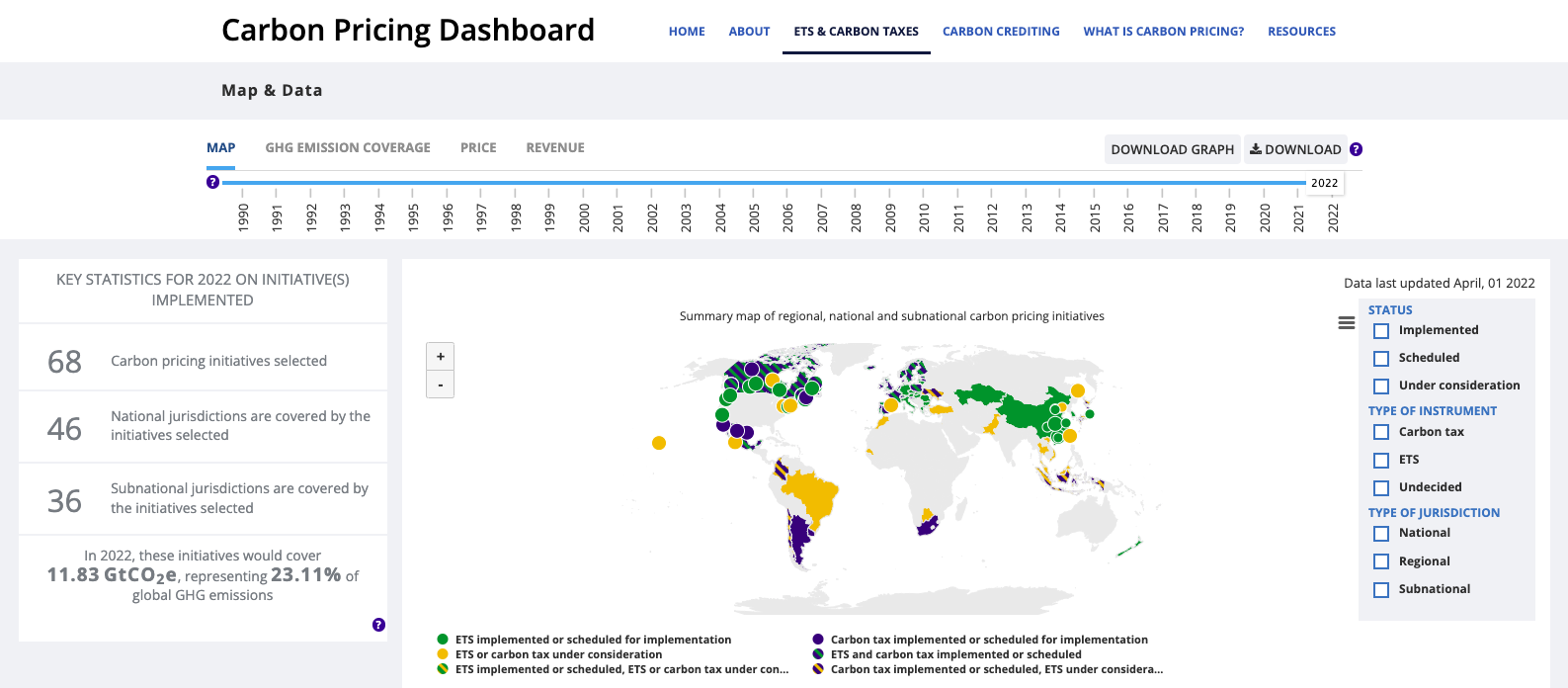

First, explore the map on the World Bank’s Carbon Pricing Dashboard (screenshot shown below). Using the selection options in the right sidebar (“TYPE OF INSTRUMENT”), compare the carbon tax programs implemented globally to the ETS (cap and trade) programs that have been implemented worldwide.

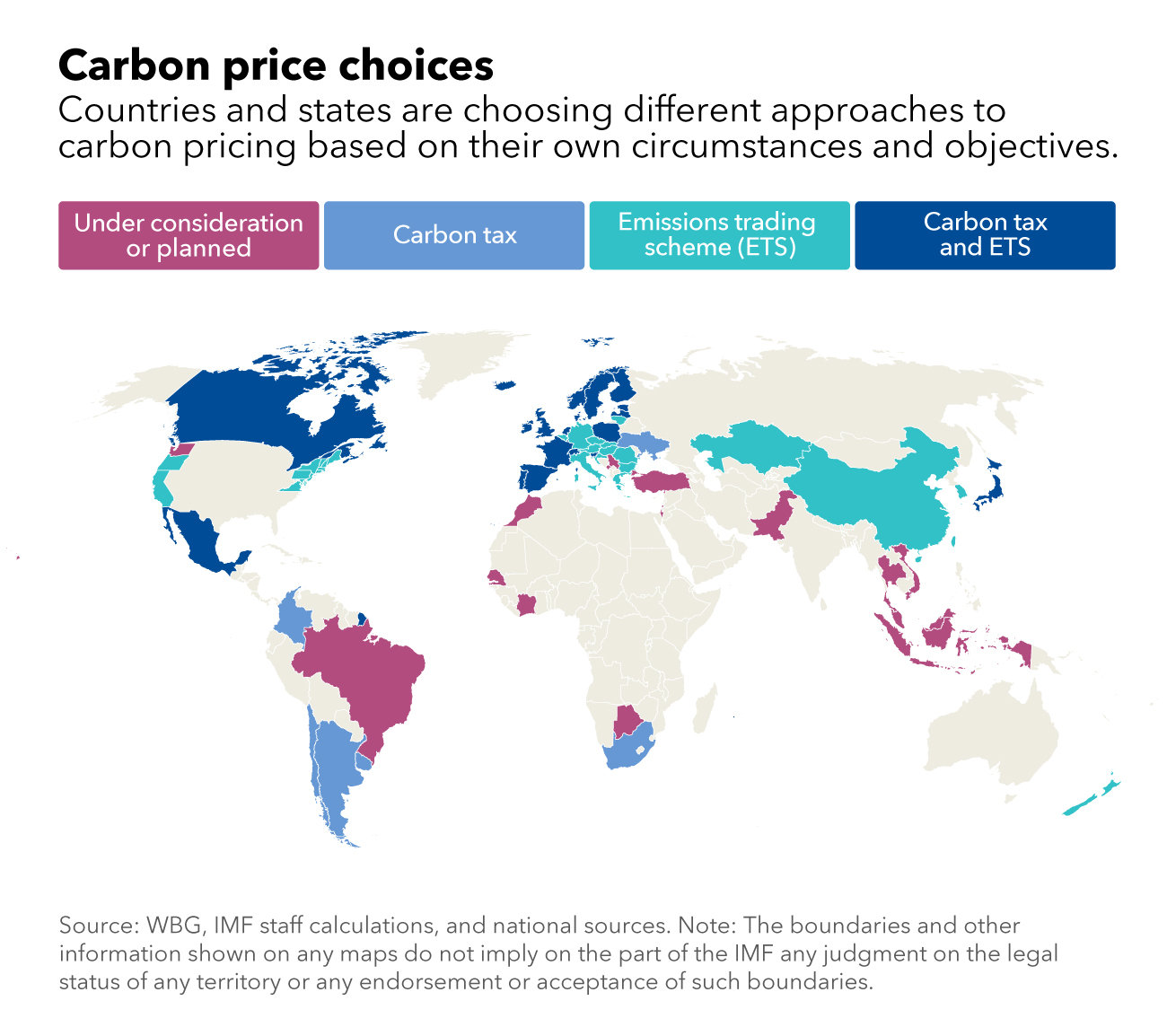

The map below shows the range of carbon pricing approaches both planned and underway across the world.

Next, we look at a few international examples of energy & climate policies to get a sense of the range of policy efforts, impacts, and challenges around the globe. Consider the economic and political differences between these countries that might help account for differences in policy efforts.

A carbon tax, the carbon pricing policy most supported by economists and environmentalists, takes different forms across different countries. Explore the dropdown below to look at examples from three different countries:

Germany

Last, we take a deeper look at Germany (below), which provides a contrast to the United States in terms of national government initiatives to address climate change, but also reveals some common challenges. Here we see how Germany’s climate and energy initiatives are shaped in part by domestic choices and in part by international markets and politics. Germany’s efforts to transform its energy system from fossil fuels and nuclear power is referred to as Energiewende (or Energy Transition).

In this section, jump to:

German National Policies toward Energiewende

German National Policies toward Energiewende

Germany has a large, dynamic economy based on manufacturing. Thus, the ambitious commitment taken by the German government to transition its energy system completely away from nuclear and fossil fuels has been seen as a very important case internationally.’

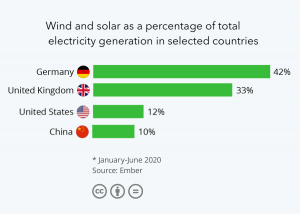

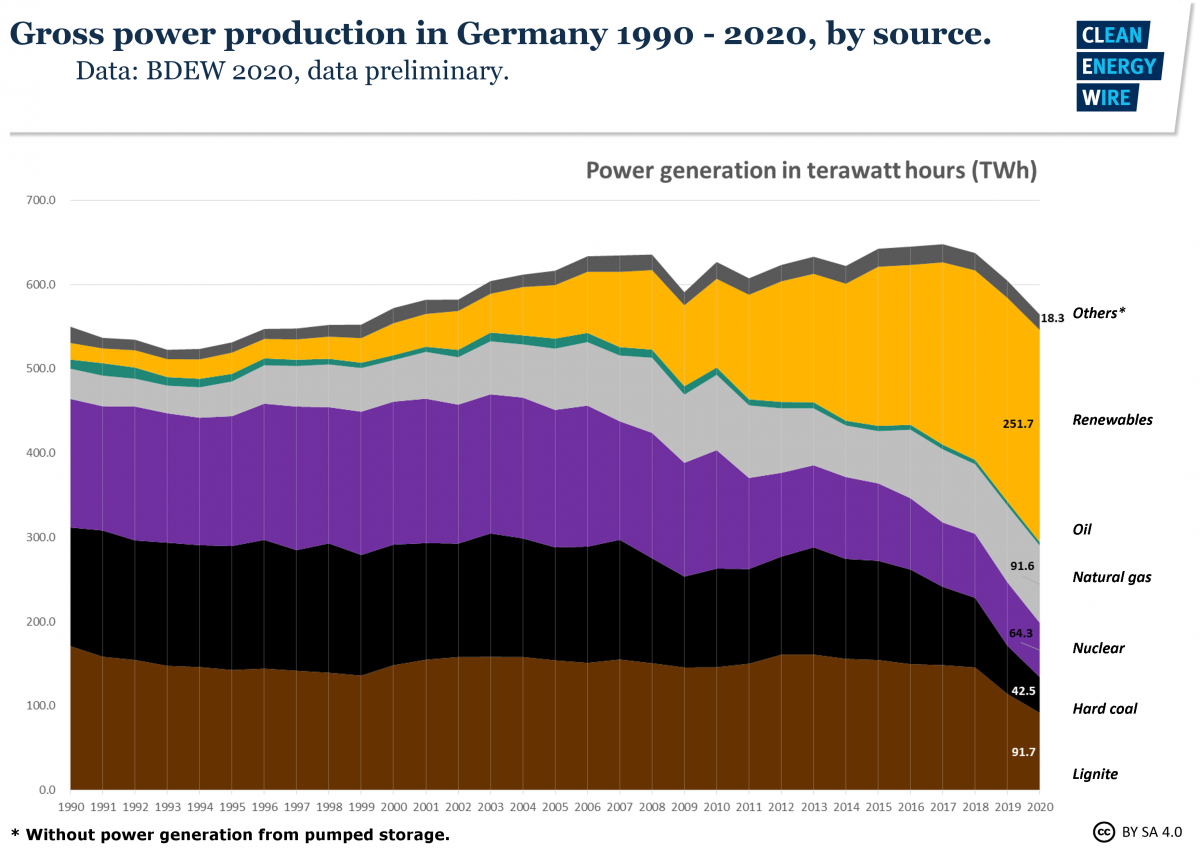

This figure (above) traces Germany’s electricity generation from 1990-2020. As you can see, electricity from renewables (wind and solar) have increased dramatically with production from nuclear and hard coal declining. These results demonstrate Germany’s heavy investment in renewable energy coupled with an almost total withdrawal from nuclear power during that time period. Natural gas and soft coal (lignite) have remained roughly the same over the past ~15 years. Also note the dip in electricity generation in 2020 due to the COVID pandemic.

The shift toward renewables has been stimulated in part by Germany’s participation in the EU’s emission trading system. More importantly, is its policy of providing incentives to homeowners and other small producers of solar and wind power for the electricity they sell back into the grid.

Required: Read only Chapter 2, “German Law gave ordinary citizens…” in the 2012 article, “Germany Has Built Clean Energy Economy That U.S. Rejected 30 Years Ago” to learn about Germany’s incentive program for small-scale electricity producers.

– Greg Nemets, “How Solar Energy Became Cheap” (2019)

Domestic Challenges

The success of Energiewende has largely been in the realm of electricity production, though many challenges still remain. Technical challenges include the need to develop electricity transmission infrastructure as the sites of electricity production diversify. In particular, wind power generated in the northern part of the country needs to be transported more efficiently to southern industrial areas. Moreover, energy storage capacity needs to expand as renewable production increases.

Politically, Germany must deal with the dependence of eastern parts of Germany on coal production (in economically-depressed areas of the former East Germany). Ultimately, Germany managed to reach its 2020 emissions reduction target, but only barely and this achievement was partly due to reduced energy use during the COVID pandemic.

International Challenges

Energiewende policy has yet to make much progress in the transportation sector, and Germany is still highly dependent on imported natural gas and oil. In 2021, more than half of Germany’s natural gas supply and about a third of its oil supply came from Russia. This heavy dependency on Russian fossil fuels has afforded Russia an immense amount of political power: in response to economic sanctions intended to weaken its war with Ukraine, Russia reduced natural gas supplies to certain European countries. This led to an energy crisis in Germany marked by gas shortages, skyrocketing prices, and a growing level of “energy poverty” throughout the country.

Some are hopeful that this energy crisis will foster accelerated efforts for renewable energy production, linking energy security to independence from foreign gas and oil. Many are calling for Germany to rethink its anti-nuclear power position and re-commission nuclear power plants. However, Germany announced in June 2022 that it will restart coal-fired power plants to combat natural gas shortages in preparation for winter. Ultimately, these negotiations highlight the tensions between domestic climate commitments, energy supply, and international geopolitics.

If you are interested in reading further about Energiewende, this website provides very useful information.

COMPLETION.

YOU ARE FINISHED!

The 2015 international agreement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is an international treaty to address climate change that came into force in 1994. Most all international actions to address climate change (Kyoto Protocol, Paris Agreement, REDD+) are managed under this international framework.

Government-funded research, tax incentives, loans, price premiums, etc., used with the aim to incentive economic or social policy.