Geography/Environmental Studies 339

International Agreements for Climate Change Mitigation

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to explain:

- The basic history of international climate change agreements;

- The basic architecture of the Kyoto Protocol;

- Strengths and weaknesses of the Kyoto Protocol;

- The various positions taken by countries in developing Kyoto and negotiating a replacement for Kyoto;

- The basic architecture of the Paris Agreement;

- Strengths and weaknesses of the Paris Agreement; and

- Looking ahead: what to expect in the future.

International Climate Agreements

Our atmosphere is truly a global commons shared by us all. It has only been relatively recently that we have recognized that human activities, through changes in the chemical composition of our atmosphere, can strongly change our climate (this new understanding is behind the idea of the Anthropocene). This brief history of international agreements to mitigate our effects on climate begins with the Montreal Protocol and ends with the Paris Climate Agreement. While our focus will be on the Kyoto Protocol and Paris Climate Agreement, it is important for us to know about earlier agreements since these have shaped the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement.

| Year | Agreement | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1987 | Montreal Protocol on Substances the Deplete the Ozone Layer | Hailed as one of the most successful international environmental agreements. Led to a significant reduction in the production of ozone-depleting substances. |

| 1988 | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) established | An intergovernmental body created under the United Nations to provide governments with scientific information to develop climate policies. Released its first assessment report in 1990 which formed the basis for the UNFCCC. |

| 1994 | United Nation's Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) | International environmental treaty adopted at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992; came into force in 1994. ‘Parties’ (154 countries) that ratified the convention voluntarily committed to reducing GHG emissions to 1990 emission levels by 2000, but treaty did not include enforcement mechanisms (commitments were ‘non-binding’). Compliance was low. |

| 1995 | First Conference of the Parties (COP1) | Parties (participating countries) to the UNFCCC meet annually to assess progress in mitigating climate change. These meeting are called conference of parties (COP). The purpose of the COPs is for countries to communicate and assess progress in mitigating climate change, establish rules and modalities, and to consider further action. |

| 1997-2005 | Kyoto Protocol adopted in 1997; comes into force in 2005. | KP adopted at the UNFCCC’s COP3. Protocol based on ‘common but differentiated responsibilities.’ During first period (2008-2012) of legally binding commitments, ratifying industrial countries had to reduce their aggregate national GHG emissions to 5-8% below their 1990 emissions levels by 2012. Non-industrial countries were exempted from reduction requirements. |

The Montreal Protocol

Ozone (03) is a molecule that can be found throughout the Earth’s atmosphere. The highest levels of ozone in the atmosphere are in the stratosphere (the outermost layer), in a region called the ozone layer. Ozone in the ozone layer absorbs most of the Sun’s ultraviolet light. This is important to life on Earth’s surface because high levels of UV exposure are dangerous to living tissues in plants, humans, and other animals (e.g. they can cause skin cancers, cataracts, DNA damage. etc.). Certain manufactured chemicals, particularly chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) used as foaming agents, refrigerants, and aerosols, are able to rise up into the stratosphere where they are then broken down into radicals by the Sun’s ultraviolet light. The radicals then cause a chemical reaction that breaks down ozone molecules and depletes the amount of ozone in the ozone layer, Ozone depletion reduces the absorption of ultraviolet radiation and allows dangerous UV rays to reach the Earth’s surface at a higher intensity.

Scientists first described this chemical reaction in the 1970s, and they first observed an erosion of the stratospheric ozone shield (an “ozone hole”) in 1985 over the Antarctica. Among other factors, the colder temperatures there result in conditions that increase rates of depletion. In 1987, an international agreement was signed to protect the ozone layer by eliminating the manufacture and use of “ozone depleting substances” such as CFCs. This agreement, called the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, came into force in 1989 and stipulated different phase-out schedules for the manufacture and use of different chemicals. Developing countries were given longer periods of time to comply with the phase-out stipulations than industrialized countries.

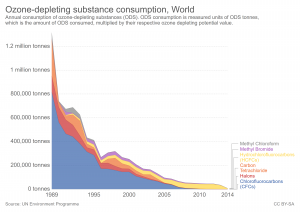

The agreement led to a dramatic global reduction in the production and consumption of these chemicals, many of which are potent greenhouse gases as well. The reduced concentration of these chemicals in our atmosphere has led to signs of ozone recovery in the stratosphere and reduction in the size of the ozone hole over the Antarctic. For more information click on Show/Hide toggle:

Show/Hide

Kofi Annan, the former UN Secretary-General, in his September 2000 address to the Millennium Assembly of the United Nations, stated the following regarding the Montreal Protocol as:

“Perhaps the single most successful international environmental agreement to date has been the Montreal Protocol, in which states accepted the need to phase out the use of ozone-depleting substances”

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)

Following the dramatic success of the Montreal Protocol, international attention shifted its focus to the need to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. GHGs are gases present in a planet’s atmosphere that absorb and emit infrared radiation in all directions. When this radiation is directed downward towards the planet’s surface, it warms the surface, resulting in what is known as the “greenhouse effect.” The main GHGs in the Earth’s atmosphere are water vapor (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and ozone (O3). As human activities have increased the levels of GHGs in the atmosphere, the greenhouse effect has accelerated and caused global warming. While the “greenhouse effect” was first hypothesized near the end of the 19th century, international concern began growing during the 1980s, with increased evidence for a rise in global temperatures along with supporting data showing an increase in carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere. In 1988, countries came together under the United Nations to form an intergovernmental scientific body called the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The IPCC is a scientific organization charged with synthesizing the current knowledge about the causes and consequences of climate change. It published its first report in 1990 with reports issued every 5-7 years.

The 1990 IPCC report formed the basis for the United Nations’ Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), an international climate treaty adopted in 1992 at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. The UNFCCC came into force in 1994 (after 154 countries signed and ratified it). The treaty committed participating countries (called ‘parties to the convention’) to voluntarily reduce GHG emissions to 1990 levels. Though the objective of the treaty is to reduce GHG emissions in the atmosphere, the treaty itself does not including binding GHG emission limits nor enforcement mechanisms to make countries reach their stated emission reduction goals (that’s why this treaty is called ‘legally non-binding’). This voluntary approach proved not to be successful in terms of GHG emission reductions. Still, the UNFCCC has served as a framework for the negotiation of subsequent international treaties (called “protocols” or “agreements”) with respect to climate change mitigation. Under the UNFCCC, participating countries–called ‘Parties to the Convention’– have met yearly at ‘Conferences of the Parties’, referred to as COP and numbered in consecutive order. The first conference, COP1, was held in Berlin, Germany in 1995, and the most recent, COP25, was held in Madrid, Spain in 2019. The purpose of the COPs is for countries to communicate and assess progress in mitigating climate change, establish rules and modalities, and to consider further action.

There are have been two important agreements made under UNFCCC:

- The Kyoto Protocol of 1997 (developed at COP3) was an attempt to move from voluntary emission reductions to an agreement with binding reduction targets. This has been the climate change agreement that was the focus of the international community through 2015.

- A successor agreement, called the Paris Agreement, was approved in Paris in December of 2015.

The Kyoto Protocol

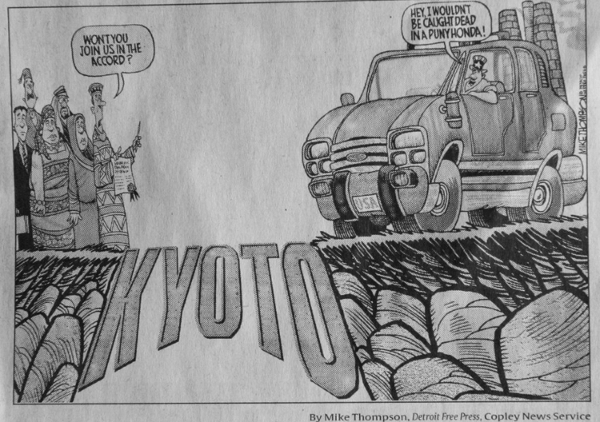

Leading up to the 1997 COP3 meeting in Kyoto, Japan, different perspectives were voiced by developing countries (global South) and industrial countries (global North) about their relative responsibilities to reduce GHG emissions. An influential article (Agarwal and Narain, 1991) presents a common argument in developing countries:

“Can we really equate the carbon dioxide contributions of gas guzzling automobiles in Europe and North America with the methane emissions of water buffalo and rice files of subsistence farmers in West Bengal or Thailand? Do these people not have the right to live? No effort has been made to separate the ‘survival emissions’ of the poor, from the “luxury emissions” of the rich.”

Agarwal, A. & S. Narain (1991) Global warming in an unequal world: A case of environmental colonialism. Earth Island Journal, Spring, 39-40.

At the same time, the United States took an especially hard line during negotiations with broad bipartisan support. Immediately prior to Kyoto, the U.S. Senate in 1997 unanimously passed the Byrd-Hagel Resolution which stated that the United States should not be a signatory to any climate change agreement that 1. does not include binding targets and timetables for developing as well as industrialized nations; or 2. causes economic harm to the United States.

At the same time, the United States took an especially hard line during negotiations with broad bipartisan support. Immediately prior to Kyoto, the U.S. Senate in 1997 unanimously passed the Byrd-Hagel Resolution which stated that the United States should not be a signatory to any climate change agreement that 1. does not include binding targets and timetables for developing as well as industrialized nations; or 2. causes economic harm to the United States.

Seeking compromise

In response to concerns expressed by developing countries, the UNFCC adopted in the Kyoto Protocol a set of “common but differentiated responsibilities” recognizing that:

- The largest share of historical and current global emissions of greenhouse gases has originated in developed countries;

- Per capita emissions in developing countries are still relatively low;

- The share of global emissions originating in developing countries will need to grow to meet their social and development needs.

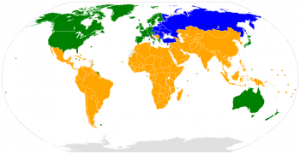

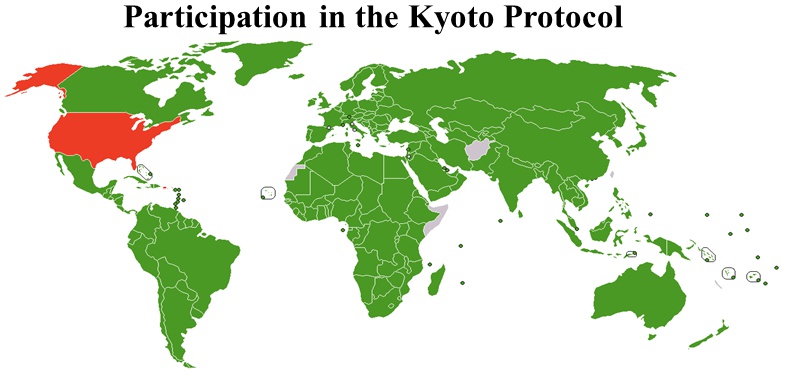

Using categories first introduced in the UNFCCC, the Kyoto Protocol classified industrial (developed) countries as Annex 1 countries (shaded green and blue in map to right). During the Protocol’s first period (2008-2012) of legally binding commitments, Annex I countries that had ratified Kyoto were required to reduce their emissions to a level generally 5-8% less than their 1990 emissions by 2012. Some Annex I countries, largely of the former Soviet Union, were sub-classified as “Economies in Transition” (shaded blue in map) and as such had fewer emission reduction obligations under the protocol.

Using categories first introduced in the UNFCCC, the Kyoto Protocol classified industrial (developed) countries as Annex 1 countries (shaded green and blue in map to right). During the Protocol’s first period (2008-2012) of legally binding commitments, Annex I countries that had ratified Kyoto were required to reduce their emissions to a level generally 5-8% less than their 1990 emissions by 2012. Some Annex I countries, largely of the former Soviet Union, were sub-classified as “Economies in Transition” (shaded blue in map) and as such had fewer emission reduction obligations under the protocol.

China, India, Brazil and other developing countries (shaded yellow in map) and exempted from the Protocol’s reduction requirements (non-Annex 1 countries).

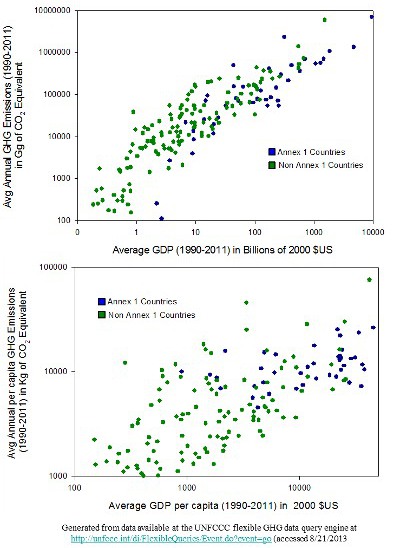

Annex 1 and Non-Annex 1 emissions and economies

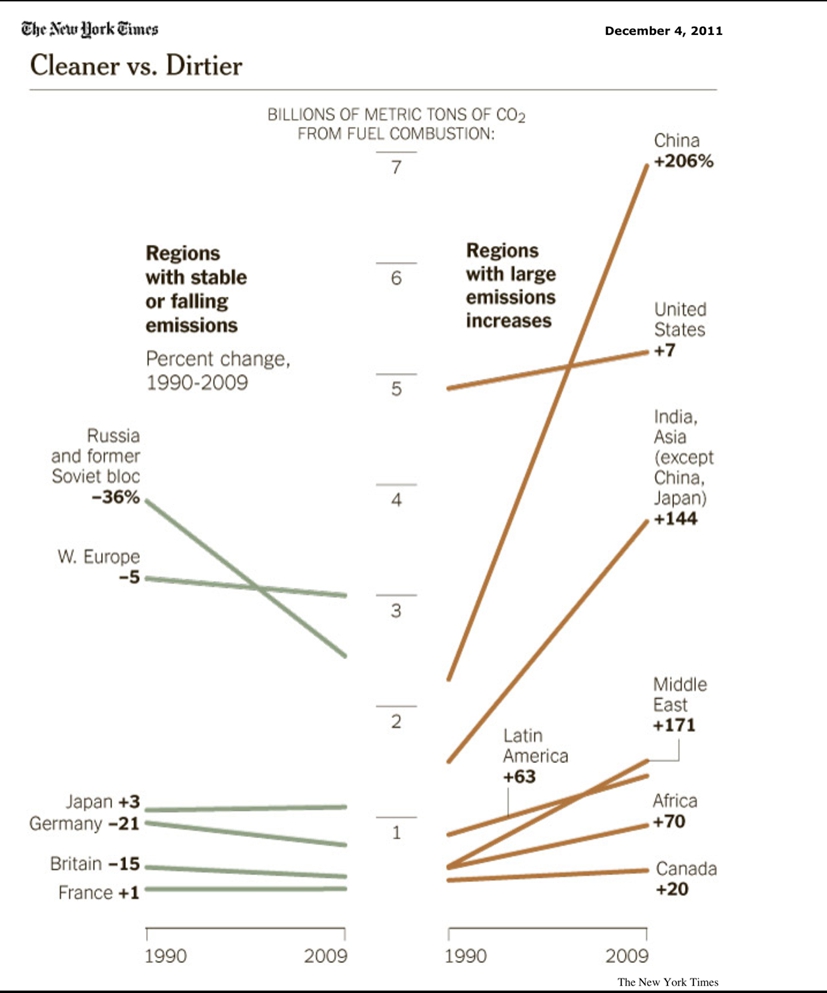

The use of the categories of Annex 1 and non-Annex 1 was made to divide the signatories to the UNFCCC with respect to their relative responsibilities to reduce GHG emissions due to their current emissions, historic emissions and capacities to reduce (given socioeconomic development needs). Any categorization, particularly into only two groups, very much simplifies the diversity of situations of countries. As we will see, the Annex 1/Non-Annex 1 categorization has created controversy about the Kyoto Protocol. To give you some sense of this, we provide two graphs and an animated visual for your consideration below.

One measure of a country’s development status is its gross domestic product (GDP), which is the annual value of goods produced and services provided within a country. The graphs below show the relationship between annual average GHG emissions and average GDP (top graph) and annual per capita (per person) GHG emissions with average per capita GDP (bottom graph). Each country is represented by a dot with Annex 1 countries in blue and non-Annex 1 countries in green. Look at these graphs and answer the short answer questions that follow.

Additionally, as we covered in the previous climate chapter (Debating responsibilities…) countries have historically been responsible for different levels of emissions throughout time. Some argue that this historical imbalance make some countries more responsible than others for the total cumulative emissions that have warmed the planet. Though much of the additional (i.e. anthropogenic) CO2 that has accumulated in the atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution would be absorbed by carbon sinks over the next 100 years, approximately 20% of this surplus carbon remains in the atmosphere for thousands of years before being absorbed. In short, this means that GHGs emitted during the Industrial Revolution are still warming the planet today. Take a second look at the following animated visual to see which countries have had the largest shares of global GHG emissions since the Industrial Revolution. (you saw this animation in Module 11)

Now use the graphs, animated visual, and the information provided in this section to answer the short answer questions that follow.

The U.S. Position on Kyoto

In 1997, the U.S., represented by then Vice President Al Gore, signed the Kyoto Protocol.Each signing country to the Protocol then had to ratify the treaty through its own political process in order for the country to be legally bound to the treaty’s terms. In the U.S., this required approval by both Congress and the Executive Branch (the President). In 2001, President Bush formally announced the U.S.’s intention to not ratify the Kyoto Protocol:

“This is a challenge that requires a 100% effort; ours, and the rest of the world’s. The world’s second-largest emitter of greenhouse gases is the People’s Republic of China. Yet, China was entirely exempted from the requirements of the Kyoto Protocol. India and Germany are among the top emitters. Yet, India was also exempt from Kyoto … America’s unwillingness to embrace a flawed treaty should not be read by our friends and allies as any abdication of responsibility. To the contrary, my administration is committed to a leadership role on the issue of climate change … Our approach must be consistent with the long-term goal of stabilizing greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere.” — The White House (2001-06-11). President Bush Discusses Global Climate Change. Press release.

In an attempt to provide greater flexibility to Annex 1 countries to meet their obligations and in order to coax the US into ratifying the protocol, country parties at the COP 6-2 meeting in Bonn, Germany (2001) agreed to incorporate three “flexibility” mechanisms into the Protocol: (1) an International Emissions Trading system allowing Annex 1 Parties to ‘trade’ their emission allowances; (2) a Joint Implementation mechanism that allows Annex 1 countries to jointly implement emission reduction projects; and (3) the Clean Development Mechanism which provides a way for Annex 1 countries to fund emissions reduction projects implemented in non-Annex 1 (developing) countries. In essence, these flexibility mechanisms provide ways for industrialized Annex 1 countries to take credit for funding emissions reduction activities outside of their country, either in other developed countries (Annex 1) (joint implementation) or in developing countries (non-Annex 1) (clean development mechanism).

In an attempt to provide greater flexibility to Annex 1 countries to meet their obligations and in order to coax the US into ratifying the protocol, country parties at the COP 6-2 meeting in Bonn, Germany (2001) agreed to incorporate three “flexibility” mechanisms into the Protocol: (1) an International Emissions Trading system allowing Annex 1 Parties to ‘trade’ their emission allowances; (2) a Joint Implementation mechanism that allows Annex 1 countries to jointly implement emission reduction projects; and (3) the Clean Development Mechanism which provides a way for Annex 1 countries to fund emissions reduction projects implemented in non-Annex 1 (developing) countries. In essence, these flexibility mechanisms provide ways for industrialized Annex 1 countries to take credit for funding emissions reduction activities outside of their country, either in other developed countries (Annex 1) (joint implementation) or in developing countries (non-Annex 1) (clean development mechanism).

These programs will be the focus of a future chapter.

Ratification of the Kyoto Protocol

To come into “force” — e.g. to become a legally binding agreement — the Kyoto Protocol needed to be ratified by at least 55 countries. and Annex 1 ratifying countries included in the 55 had to together contribute at least 55% of global greenhouse gas emissions in 1990. The Kyoto Protocol came “into force” in February 2005 after the ratification of the protocol by Russia in November 2004.

The United States (depicted in the map above in red) was alone among parties to the UNFCCC in refusing to ratify the Kyoto Protocol and therefore was not obligated to meet the Protocol’s GHG reduction targets. The Table below lists the top 15 countries in terms of aggregate GHG emissions in 2010.

| Country | CO2 equiv emissions (millions of metric tons) | % of Total | per capita CO2 emissions (metric tons) | Annex 1 Ratifier of Kyoto |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 8,321 | 26.2 | 6.3 | N/A |

| United States of America | 5,610 | 17.7 | 18.1 | no |

| India | 1,696 | 5.3 | 1.4 | N/A |

| Russia | 1,634 | 5.1 | 11.7 | yes |

| Japan | 1,164 | 3.7 | 9.2 | yes |

| Germany | 794 | 2.5 | 9.6 | yes |

| South Korea | 579 | 1.8 | 11.9 | |

| Iran | 560 | 1.8 | 7.3 | N/A |

| Canada | 549 | 1.7 | 16.3 | yes |

| United Kingdom | 532 | 1.7 | 8.5 | yes |

| Saudi Arabia | 478 | 1.5 | 18.6 | N/A |

| South Africa | 465 | 1.5 | 9.5 | N/A |

| Brazil | 454 | 1.4 | 2.3 | N/A |

| Mexico | 445 | 1.4 | 4.0 | N/A |

| Italy | 416 | 1.3 | 7.2 | yes |

The Effectiveness of the Kyoto Protocol

During the first legally binding commitment period (2008-2012), The Kyoto Protocol required that Annex 1 ratifying countries reduce their GHG emissions by 5-8% below 1990 levels by 2012. This figure shows the change in greenhouse gas emissions by countries from 1990-2011.

Renewal or Replacement of the Kyoto Protocol?

To extend the Kyoto Protocol beyond 2012, the agreement had to be either renewed or replaced (per the Protocol’s original stipulations). From November 28 to December 11, 2011, the 17th session of the Conference of the Parties (COP17) to the UNFCCC was held in Durban, South Africa to seek renewal.

The COP 17 agreed:

- to seek a new legally-binding agreement by 2015 including that included all countries, which would take effect in 2020;

- That the Kyoto Protocol would remain in effect with a second commitment period (2012-2020) until the new agreement was made, though only some countries indicated that they would renew their commitments (Russia, Japan, and New Zealand did not take on new targets in the second commitment period, and Canada withdrew from the Protocol in 2012); and

- to launch a Green Climate Fund that would provide US$100bn per year to help poor countries adapt to climate change. [however, this quantity has yet to be met]

After the COP17 in Durban, three additional COPs (18-20) were held between 2012-2014, each focusing on developing a new agreement to replace the Kyoto Protocol. Three important areas of concern arose during this time:

- Growing strains in the Developing World Alliance between rapidly-growing middle-income countries emitting relatively large amounts of greenhouse gases (e.g., China, India, South Korea, Brazil, Mexico) and the poorest countries experiencing many of the impacts of climate change (Island Nations, African countries, Bangladesh, etc.).

- A greater recognition of the differential impacts of climate change on the poorest of developing countries with a concomitant need for the industrialized world to fund climate change mitigation and adaptation.

- Considerable anxiety about the need to resolve the stand-off among the largest emitters (China, U.S., and India) related to their responsibilities to reduce their GHG emissions.

In 2014, hopes were raised with the news of the joint announcement that the U.S. and China would both seek to reduce their GHG emissions. While not an enforceable treaty, the U.S. stated that it intended to reduce its aggregate emissions to 26%-28% below its 2005 level by 2025. China stated that it intended to start reducing aggregate emissions by 2030.

The Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement was designed and agreed upon at COP21 in Paris in 2015 by nearly every nation. It is a legally-binding climate change mitigation treaty designed to be the successor to the Kyoto Protocol. To date, 195 countries have signed the Agreement and 187 Parties (of 197 Parties to the Convention) have ratified it. This represents 97% of global emissions. The only significant emitters which are not Parties to the Agreement are Iran and Turkey (But see more below on the United States’ stated intention to withdraw from the Agreement).

In order for the Agreement to formally come into force, at least 55 countries accounting in total for at least 55% of global greenhouse gas emissions had to ratify the treaty. This occurred in Oct of 2016 when 74 countries–including the US, the EU, India, and China–ratified the deal. The Agreement then formally came into force on November 4, 2016.

The broad goals of the Agreement are:

- to keep global average temperature rise well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-Industrial levels while pursuing efforts to limit the temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius;

- to provide a transparent framework for countries to set, monitor, verify, and publicly report on their emissions-reduction targets;

- and to strengthen developing countries’ ability to mitigate and adapt to climate change impacts by setting up a fund through which developed countries can channel money to developing countries for climate change mitigation and adaptation purposes.

How Does the Agreement Aim to Achieve These Goals?

For COP21, countries were asked to develop statements of “intended nationally determined contributions” (INDCs) which represent each country’s individual commitments (a) to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (a mitigation strategy) and/or (b) to reduce their vulnerability to climate change (an adaptation strategy). In contrast to the Kyoto Protocol, these self-determined country-specific contributions formed the basis for the Paris Agreement.

Once a country formally ratified the Agreement, the country’s “intended nationally determined contributions” were replaced by nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to ‘the Agreement. Ratifying countries are legally required by the Agreement to set, monitor, verify, and publicly report on their NDCs every five years. However, unlike the Kyoto Protocol, there are no legal requirements regarding how or by how much countries must reduce their emissions, and there are no financial penalties for not meeting their NDCs. Rather, the Agreement relies more on the enhanced transparency of the framework to foster a sense of global peer pressure and to make it easier to track which countries are setting and meeting ambitious goals, and which are not. One result of this approach, however, is that countries’ NDCs vary greatly both in scope and ambition.

With respect to mitigation, these commitments are highly varied and are normally stated as a reduction target:

- Commitments to reduce aggregate greenhouse gas emissions.

- Commitments to reduce the energy intensity (energy use per unit of GDP) or emissions intensity of its economy (GHG emissions per unit of GDP)

These commitments are seen to be met by achieving a certain percentage relative to a specified baseline, such as:

- The value of the target (aggregate emissions or fossil fuel intensity) in year X.

- The projected value of the target by achievement year based on a “business as usual” (BAU) scenario.

to be achieved by a certain year or range of years… with certain conditionalities (normally funding from industrialized countries)

Follow this link to open the World Resources Institute’s page (in a separate window) that tracks these commitments by country. To answer the following questions, enter the country name (India, China, United States or European Union) in the search box:

And select ‘NDC-Overview’ to read the summary of its emission reduction commitment.

The stated overall goal of the Paris Agreement is to keep global temperature increases well below 2 degrees C and closer to 1.5 degrees C. A number of commentators have made the point that even if these voluntary emission reductions were met within the stated time frames, global temperature increases would likely exceed 2 degrees C.

Climate Finance for Developing Countries in the Paris Agreement

You’ll recall that at COP17 in 2011 Parties to the UNFCCC agreed to establish a Green Climate Fund (GCF) that would provide US$100 billion per year to help poor countries adapt to climate change; however, developed country Parties have yet to achieve this level of funding. In the first round of funding for the GCF in 2014, 44 countries–including 23 traditional contributors, 12 other developed countries, and nine developing countries– pledged a cumulative total of US$10.3 billion to the Fund; however, parts of the pledged amount have yet to be transferred to the GCF.

The Paris Agreement upholds the acknowledgement, first made in the UNFCCC, that countries have significantly different capacities to prevent and adapt to the consequences of climate change. In Article 9, the Paris Agreement stipulates that developed country Parties must provide financial resources to the GCF to help developing country Parties with both mitigation and adaptation. Specifically, the Agreement requires developed country Parties to biennially provide transparent information on how (i.e. grants, loans, etc.) and how much funding they are currently pledging to developing country Parties (through the GCF) to assist with their climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies, and how much they expect to provide in the near future.

Beyond this requirement for transparency, the Paris Agreement also contains language that strongly urges but does not require developed country Parties to increase their level of financial support in order to achieve the goal of jointly providing USD$100 billion annually to developing countries by 2020 for mitigation and adaptation. It also states that that prior to 2025, country Parties must set a new collective target goal that starts at no less than USD 100 billion per year. Finally, the Agreement also highlights the acute need of countries that are particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change and have significant capacity constraints, like the least developed countries and small island developing States.

For those of you interested, you can see the status of countries’ pledges to the Green Climate Fund by following this link to the World Resource Institute’s Green Climate Fund Contributions Calculator.

U.S. announces intention to withdraw from Paris Accord

On June 1, 2017, U.S. President Trump announced his intention to withdraw from the Paris Climate Accord:

“As president, I can put no other consideration before the wellbeing of American citizens. The Paris climate accord is simply the latest example of Washington entering into an agreement that disadvantages the United State to the exclusive benefit of other countries, leaving American workers – who I love – and taxpayers to absorb the cost in terms of lost jobs, lower wages, shuttered factories, and vastly diminished economic production

For example, under the agreement, China will be able to increase these emissions by a staggering number of years – 13. They can do whatever they want for 13 years. Not us. India makes its participation contingent on receiving billions and billions and billions of dollars in foreign aid from developed countries. There are many other examples. But the bottom line is that the Paris accord is very unfair, at the highest level, to the United States.”

— Statement by President Trump on the Paris Climate Accord. The White House. Office of the Press Secretary. Rose Garden. June 01, 2017.

On Nov 4 2019, the United States made President Trump’s intention official: the U.S. notified the UNFCCC of its decision to withdraw from the Agreement. Per the Agreement’s terms outlining the process for withdrawal, the agreement must be in force for three years before any country can formally announce its intention to withdraw, which is why the U.S. had to wait until Nov 2019 to announce its withdrawal intentions. Then, the agreement stipulates that a country must wait a year after formally announcing its withdrawal intention before it can actually exit the Agreement. On Nov. 4, 2020, one day after President Trump lost his re-election bid, the U.S.’s exit from the Paris Agreement took effect. However, only hours after taking the oath of office, President Joe Biden announced the U.S. would rejoin the Paris Agreement, and this took effect 30 days later (on 2/19/21). The Biden administration must now get a divided Congress to pass legislation tho put the U.S. back on track to meet its commitments.

In the period between President’s Trump announcement to withdraw the U.S. from the Agreement and the country’s formal exit in 2020, the U.S. was required to continue participating in the COP meetings and climate negotiations. However, it did so in a grandstanding fashion. For example, at the 2018 COP 24 in Katowice, Poland, the United States (along with Australia) convened a panel extolling the merits of fossil fuel energy–particularly coal–that elicited protests (see photo). Moreover, the United States, along with Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait were able to water down the COP24 response to the IPCC’s special report about the impacts of a 1.5 degree C increase in global mean temperature that was elicited by the Paris Agreement itself and released approximately two months before COP24.

Despite the lack of support for the Paris Agreement by President Trump’s administration during 2017-2020, there were significant actions taken by local and state governments and private companies in the U.S. to reduce greenhouse gas emissions during this period. These actions are covered in the chapter on energy policy, but there are some estimates that these actions have advanced us significantly toward our Paris Agreement commitments. For those of you who are interested, a 2018 report making this argument by the climate action committee called America’s Pledge on Climate can be accessed through this link.

COP25 and Ambitious Targets

The most recent annual UN climate conference, COP25, took place in December 2019 in Madrid, Spain. COP25 was intended to be a stepping stone towards the next climate conference, in which countries will set new NDCs and funding commitments (the COP26 conference in Glasgow was re-scheduled for Nov 2021 due to to the COVID-19 pandemic).

COP25 took place after several reports confirmed that Party countries’ pledges to reduce emissions are insufficient if we want to avoid a 3.2 degrees Celsius rise in global temperature by 2100, more than double the ambitious 1.5 degrees Celsius goal of the Paris Agreement. Notably, a massive protest march took place in the middle of COP25 to call attention to this gap between current emissions reduction progress and the Agreement target goals to limit warning. Internationally renowned climate activist Greta Thunberg joined the protest march after her symbolic transatlantic journey by sailboat to participate in the protest against climate inaction.

Because country Parties’ NDCs are currently vastly insufficient, countries at COP25 attempted to agree on a paragraph of text that would call for greater ambition from all country Parties when setting the next NDC targets. According to the Agreement’s terms, NDCs must be set every five years and each successive NDC is supposed to “represent a progression” and “reflect [each country’s’] highest possible ambition.” However, many countries used their original INDCS–many of which go through 2030–to set their five-year NDC target. As a result, some countries have stated that they will simply be “re-communicating” the commitments they made in their INDCs, as opposed to setting new, more ambitious NDCs. To date, according to the World Resource Institute’s NDC tracker 103 countries, representing only 38.4% of global emissions, have stated they intend to enhance the mitigation ambition in their NDCs by COP26 (2021). Only one of these 103 countries–China– is a high emitter, and many are small and vulnerable developing nations.

Additionally, country Parties at COP25 failed to come to a consensus about what the word “ambition” should mean, with some–particularly developed countries– interpreting “ambition” more narrowly as a means to increase emissions reductions efforts after 2020, and others–especially India and other developing countries–arguing for a broader interpretation of “ambition” that would include increases to pledged climate finance and efforts to strengthen adaptation and capacity in poorer countries. The latter pointed to the failure of many developed countries to fulfill their pre-2020 NDC pledges and thus posing a threat to the integrity of the Paris Agreement and to any chance of thwarting global warming. The lack of support from the United States has complicated and slowed the commitments made by others.

At the close of COP25, the final agreed upon text ended up much weaker than first proposed. The text calls attention to the gap between current ambition and the Agreement’s global temperature goals and urges parties to consider the gap when “[re]communicat[ing]” or “updat[ing]” their NDCs. It also calls for “round tables” on ambition at COP26 and COP27.

A term referring to a proposed new geologic epoch where human activities are fundamentally altering global physical systems (climate, landforms, nutrient cycles etc.). It is seen to replace the current geologic epoch of the Holocene which is the more conventionally recognized geologic epoch today.

This refers to how certain gases in the Earth's atmosphere retain energy from the sun's rays by trapping infrared energy (as in the Climate 101 video). The greenhouse effect has existed for millions of years, and is necessary for the Earth to be warm enough to maintain life. When we INCREASE the greenhouse effect by increasing the proportion of greenhouse gases, we experience global warming.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is an international scientific body with almost 200 member countries formed in 1988 under the auspices of the World Meteorological Organization and the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP).

The IPCC reviews and synthesizes existing scientific literature on climate change, publishing multi-volume comprehensive assessment reports at approximately 6-7 year intervals (1990, 1995, 2001, 2007, 2014, and 2021) as well as special reports.