47 Bond Length and Strength (M8Q4)

Introduction

Learning Objectives for Bond Length and Bond Strength

- Relate trends in atom size and bond order to rationalize and support observed bond lengths and strengths.

| Covalent Bonds | Ionic Bond Strength and Lattice Energy | - Use tabulated bond enthalpies to calculate approximate reaction enthalpies.

| Calculating Bond Enthalpies |

| Key Concepts and Summary | Key Equations | Glossary | End of Section Exercises |

Covalent Bonds

Stable molecules exist because covalent bonds hold the atoms together. We measure the strength of a covalent bond by the energy required to break it, that is, the energy necessary to separate the bonded atoms. Separating any pair of bonded atoms requires energy. The stronger a bond, the greater the energy required to break it.

The energy required to break a specific covalent bond in one mole of gaseous molecules is called the bond energy or the bond dissociation energy. The bond energy for a diatomic molecule is defined as the standard enthalpy change for the endothermic reaction:

For example, the bond energy of the pure covalent H–H bond is 436 kJ per mole of H–H bonds broken:

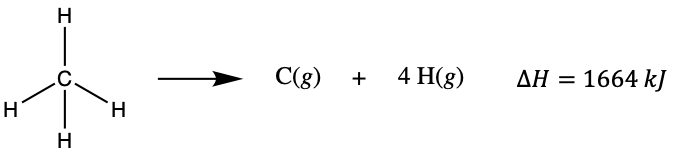

Molecules with three or more atoms have two or more bonds. The sum of all bond energies in such a molecule is equal to the standard enthalpy change for the endothermic reaction that breaks all the bonds in the molecule. For example, the sum of the four C–H bond energies in CH4, 1664 kJ, is equal to the standard enthalpy change of the reaction:

The average C–H bond energy is 1664/4 = 416 kJ/mol because there are four moles of C–H bonds broken per mole of the reaction. Although the four C–H bonds are equivalent in the original molecule, they do not each require the same energy to break; once the first bond is broken (which requires 439 kJ/mol), the remaining bonds are easier to break. The average C-H bond energy is not only averaged over each C-H bond broken within a single molecule, but the average of C-H bond energies of many molecules. For example, ethane, C2H6, has an actual C-H bond energy closer to 423 kJ/mol, lower than the 439 kJ/mol of methane. The 416 kJ/mol value is the average, not the exact value required to break any one bond in any one molecule.

The strength of a bond between two atoms increases as the number of electron pairs in the bond increases. Generally, as the bond strength increases, the bond length decreases. Thus, we find that triple bonds are stronger and shorter than double bonds between the same two atoms; likewise, double bonds are stronger and shorter than single bonds between the same two atoms. Average bond energies for some common bonds appear in Table 1 and Appendix G, and a comparison of bond lengths for some common bonds appears in Table 2 and Appendix G. When one atom bonds to various atoms in a group, the bond strength typically decreases (and bond length increases) as we move down the group. For example, C–F is 485 kJ/mol and 141 pm, C–Cl is 327 kJ/mol and 176 pm, and C–Br is 285 kJ/mol and 191 pm.

Average Bond Enthalpy

In kJ/mol

| I | Br | Cl | S | P | Si | F | O | N | C | H | |

| H | 299 | 366 | 431 | 347 | 322 | 323 | 566 | 467 | 391 | 416 | 436 |

| C | 213 | 285 | 327 | 272 | 264 | 301 | 485 | 358 | 285 | 346 | |

| N | - | - | 193 | - | ~200 | 335 | 272 | 201 | 160 | ||

| O | 201 | - | 205 | - | ~340 | 368 | 190 | 146 | |||

| F | - | 238 | 255 | 326 | 490 | 582 | 158 | ||||

| Si | 234 | 310 | 391 | 226 | - | 226 | |||||

| P | 184 | 264 | 319 | - | 209 | ||||||

| S | - | 213 | 255 | 226 | Multiple Bonds | Multiple Bonds | |||||

| Cl | 209 | 217 | 242 | N=N | 418 | C=C | 598 | ||||

| Br | 180 | 193 | N≡N | 946 | C≡C | 813 | |||||

| I | 151 | C=N | 616 | C=O in CO2 | 803 | ||||||

| C≡N | 866 | C=O carbonyl | 695 | ||||||||

| N=O | 607 | C≡O | 1073 | ||||||||

| O=O in O2 | 498 | N≡O | 632 | ||||||||

| Data from Cotton, F.A., Wilkinson, G. and Gaus, P.L., Basic Inorganic Chemistry, 3rd ed., New York: Wiley, 1995. Corrected values for C-C and C-O from Cottrell, T.L., The Strengths of Chemical Bonds, 2ed., London:Butterworths, 1958. |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Table 1: Bond Enthalpies in kJ/mol.

Average Bond Length

In picometers, (pm)

| I | Br | Cl | S | P | Si | F | O | N | C | H | |

| H | 161 | 142 | 127 | 132 | 138 | 145 | 92 | 94 | 98 | 110 | 74 |

| C | 210 | 191 | 176 | 181 | 187 | 194 | 141 | 143 | 147 | 154 | |

| N | 203 | 184 | 169 | 174 | 180 | 187 | 134 | 136 | 140 | ||

| O | 199 | 180 | 165 | 170 | 176 | 183 | 130 | 148 | |||

| F | 197 | 178 | 163 | 168 | 174 | 181 | 128 | ||||

| Si | 250 | 231 | 216 | 221 | 227 | 234 | |||||

| P | 243 | 224 | 209 | 214 | 220 | ||||||

| S | 237 | 218 | 203 | 208 | Multiple Bonds | Multiple Bonds | |||||

| Cl | 232 | 213 | 200 | N=N | 120 | C=C | 134 | ||||

| Br | 247 | 228 | N≡N | 110 | C≡C | 121 | |||||

| I | 266 | C=N | 127 | C=O in CO2 | 116 | ||||||

| C≡N | 115 | C=O carbonyl | 121 | ||||||||

| N=O | 115 | C≡O | 113 | ||||||||

| O=O in O2 | 121 | N≡O | 115 | ||||||||

Table 2: Average bond lengths in picometers (pm).

We can use bond energies to calculate approximate enthalpy changes for reactions where enthalpies of formation are not available. Calculations of this type will also tell us whether a reaction is exothermic or endothermic. An exothermic reaction (-ΔH, heat released) results when the bonds in the products are stronger than the bonds in the reactants. An endothermic reaction (+ΔH, heat absorbed) results when the bonds in the products are weaker than those in the reactants.

Calculating Enthalpy Change

The enthalpy change, ΔH, for a chemical reaction is approximately equal to the sum of the energy required to break all bonds in the reactants (energy “in”, positive sign) plus the energy released when all bonds are formed in the products (energy “out,” negative sign). This can be expressed mathematically in the following way:

ΔHreaction = ∑ (energy of bonds broken) - ∑ (energy of bonds formed)

In this expression, the symbol Ʃ means “the sum of” and we sum the bond energy in kilojoules per mole, which is always a positive number. The bond energy is obtained from a table (like Table 1/Appendix G) and will depend on whether the particular bond is a single, double, or triple bond. Thus, in calculating enthalpies in this manner, it is important that we consider the bonding in all reactants and products. Because bond energy values are typically averages for one type of bond in many different molecules, this calculation provides a rough estimate, not an exact value, for the enthalpy of reaction.

Consider the following reaction:

or

To form two moles of HCl, one mole of H–H bonds and one mole of Cl–Cl bonds must be broken. The energy required to break these bonds is the sum of the bond energy of the H–H bond (436 kJ/mol) and the Cl–Cl bond (242 kJ/mol). During the reaction, two moles of H–Cl bonds are formed (bond energy = 431 kJ/mol), releasing 2 × 431 kJ; or 862 kJ. Because the bonds in the products are stronger than those in the reactants, the reaction releases more energy than it consumes:

ΔHreaction = ∑ (energy of bonds broken) - ∑ (energy of bonds formed)

= [(H-H) + (Cl-Cl)] - 2(H-Cl)

= [436 + 242] - 2(431) = -184 kJ

This excess energy is released as heat, so the reaction is exothermic. Appendix F gives a value for the standard molar enthalpy of formation of HCl(g), ΔHf°, of -92.307 kJ/mol. Twice that value is –184.6 kJ, which agrees well with the answer obtained earlier for the formation of two moles of HCl.

Example 1

Using Bond Energies to Calculate Approximate Enthalpy Changes

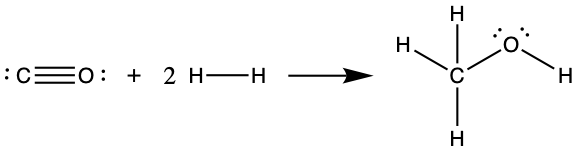

Methanol, CH3OH, may be an excellent alternative fuel. The high-temperature reaction of steam and carbon produces a mixture of the gases carbon monoxide, CO, and hydrogen, H2, from which methanol can be produced. Using the bond energies in Table 1, calculate the approximate enthalpy change, ΔH, for the reaction here:

Solution

First, we need to write the Lewis structures of the reactants and the products:

From this, we see that ΔH for this reaction involves the energy required to break a C–O triple bond and two H–H single bonds, as well as the energy produced by the formation of three C–H single bonds, a C–O single bond, and an O–H single bond. We can express this as follows:

ΔH = ∑ (energy of bonds broken) - ∑ (energy of bonds formed)

= [(C≡O) + 2(H-H)] - [3(C-H) + (C-O) + (O-H)]

Using the bond energy values in Table 1, we obtain:

ΔH = [1073 + 2(436)] - [3(416) + 358 + 467]

= -128 kJ

We can compare this value to the value calculated based on ΔHf° data from Appendix F:

ΔH = [ΔHf°(CH3OH(g))] - [ΔHf°(CO(g)) + 2 × ΔHf°(H2)]

= [-200.66] - [-110.525 + 2 × 0]

= -90.135 kJ

Note that there is a fairly significant gap between the values calculated using the two different methods. This occurs because bond energy values are the average of different bond strengths; therefore, they often give only rough agreement with other data.

Check Your Learning

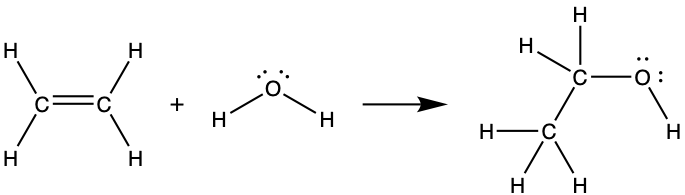

Ethyl alcohol, CH3CH2OH, was one of the first organic chemicals deliberately synthesized by humans. It has many uses in industry, and it is the alcohol contained in alcoholic beverages. It can be obtained by the fermentation of sugar or synthesized by the hydration of ethylene in the following reaction:

Using the bond energies in Table 1, calculate an approximate enthalpy change, ΔH, for this reaction.

Answer:

–55 kJ

Ionic Bond Strength and Lattice Energy

An ionic compound is stable because of the electrostatic attraction between its positive and negative ions. The lattice energy of a compound is a measure of the strength of this attraction. The lattice energy (ΔHlattice) of an ionic compound is defined as the energy required to separate one mole of the solid into its component gaseous ions. For the ionic solid, MX, the lattice energy is the enthalpy change of the process:

Note that we are using the convention where the ionic solid is separated into ions, so our lattice energies will be endothermic (positive values). Some texts use the equivalent but opposite convention, defining lattice energy as the energy released when separate ions combine to form a lattice and giving negative (exothermic) values. Thus, if you are looking up lattice energies in another reference, be certain to check which definition is being used. In both cases, a larger magnitude for lattice energy indicates a more stable ionic compound. For sodium chloride, ΔHlattice = 769 kJ. Thus, it requires 769 kJ to separate one mole of solid NaCl into gaseous Na+ and Cl– ions. When one mole each of gaseous Na+ and Cl– ions form solid NaCl, 769 kJ of heat is released.

The lattice energy ΔHlattice of an ionic crystal can be expressed by the following equation (derived from Coulomb’s law, governing the forces between electric charges):

in which C is a constant that depends on the type of crystal structure; Z+ and Z– are the charges on the ions; and Ro is the interionic distance (the sum of the radii of the positive and negative ions). Thus, the lattice energy of an ionic crystal increases rapidly as the charges of the ions increase and the sizes of the ions decrease. When all other parameters are kept constant, doubling the charge of both the cation and anion quadruples the lattice energy. For example, the lattice energy of LiF (Z+ and Z– = 1) is 1023 kJ/mol, whereas that of MgO (Z+ and Z– = 2) is 3900 kJ/mol (Ro is nearly the same—about 200 pm for both compounds).

Different interatomic distances produce different lattice energies. For example, we can compare the lattice energy of MgF2 (2957 kJ/mol) to that of MgI2 (2327 kJ/mol) to observe the effect on lattice energy of the smaller ionic size of F– as compared to I–.

Example 2

Lattice Energy Comparisons

The precious gem ruby is aluminum oxide, Al2O3, containing traces of Cr3+. The compound Al2Se3 is used in the fabrication of some semiconductor devices. Which has the larger lattice energy, Al2O3 or Al2Se3?

Solution

In these two ionic compounds, the charges Z+ and Z– are the same, so the difference in lattice energy will depend upon Ro. The O2– ion is smaller than the Se2– ion. Thus, Al2O3 would have a shorter interionic distance than Al2Se3, and Al2O3 would have the larger lattice energy.

Check Your Learning

Zinc oxide, ZnO, is a very effective sunscreen. How would the lattice energy of ZnO compare to that of NaCl?

Answer:

ZnO would have the larger lattice energy because the Z values of both the cation and the anion in ZnO are greater, and the interionic distance of ZnO is smaller than that of NaCl.

Lattice energies calculated for ionic compounds are typically much higher than bond dissociation energies measured for covalent bonds. Whereas lattice energies typically fall in the range of 600–4000 kJ/mol (some even higher), covalent bond dissociation energies are typically between 150–400 kJ/mol for single bonds. Keep in mind, however, that these are not directly comparable values. For ionic compounds, lattice energies are associated with many interactions, as cations and anions pack together in an extended lattice. For covalent bonds, the bond dissociation energy is associated with the interaction of just two atoms.

The Born-Haber Cycle

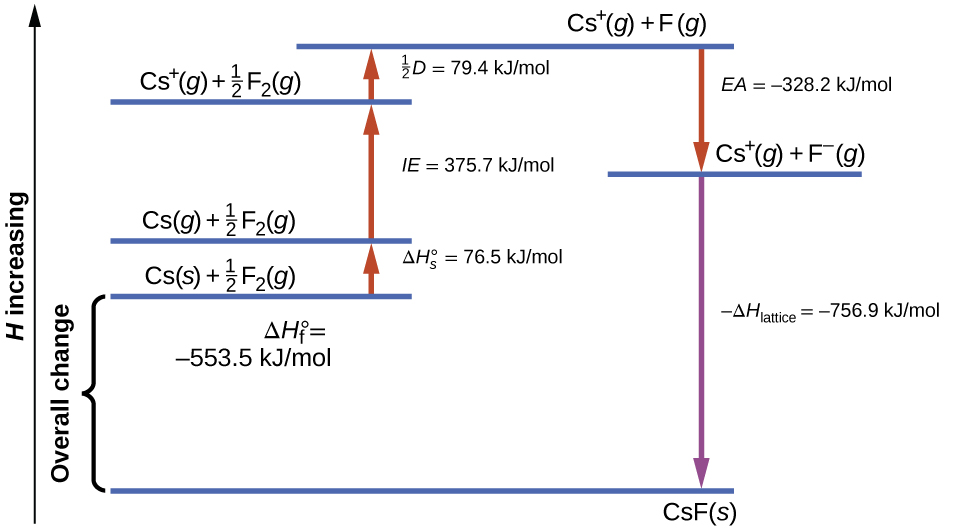

It is not possible to measure lattice energies directly. However, the lattice energy can be calculated using the equation given above or by using a thermochemical cycle. The Born-Haber cycle is an application of Hess’s law that breaks down the formation of an ionic solid into a series of individual steps:

- ΔHf°, the standard enthalpy of formation of the compound

- IE, the ionization energy of the metal

- EA, the electron affinity of the nonmetal

- ΔH°sublimation, the enthalpy of sublimation of the metal

- D, the bond dissociation energy of the nonmetal

- ΔH°lattice, the lattice energy of the compound

Figure 1 diagrams the Born-Haber cycle for the formation of solid cesium fluoride.

We begin with the elements in their most common states, Cs(s) and F2(g). The ΔH°sublimation represents the conversion of solid cesium into a gas, and then the ionization energy converts the gaseous cesium atoms into cations. In the next step, we account for the energy required to break the F–F bond to produce fluorine atoms. Converting one mole of fluorine atoms into fluoride ions is an exothermic process, so this step gives off energy (the electron affinity) and is shown as decreasing along the y-axis. We now have one mole of Cs cations and one mole of F anions. These ions combine to produce solid cesium fluoride. The enthalpy change in this step is the negative of the lattice energy, so it is also an exothermic quantity. The total energy involved in this conversion is equal to the experimentally determined enthalpy of formation, ΔHf°, of the compound from its elements. In this case, the overall change is exothermic.

Hess’s law can also be used to show the relationship between the enthalpies of the individual steps and the enthalpy of formation. Table 3 shows this for sodium chloride, NaCl.

| Enthalpy of sublimation of Na(s) | Na(s) → Na(g) ΔH = ΔHºsublimation = 109 kJ |

| One-half of the bond energy of Cl2 | [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex]Cl2(g) → Cl(g) ΔH = [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex]D = 121 kJ |

| Ionization energy of Na(g) | Na(g) → Na+(g) + e- ΔH = IE = 496 kJ |

| Negative of the electron affinity of Cl | Cl(g) + e- → Cl-(g) ΔH = -EA = -368 kJ |

| Negative of the lattice energy of NaCl(s) | Na+(g) + Cl-(g) → NaCl(s) ΔH = -ΔHlattice = ? |

| Enthalpy of formation of NaCl(s), add steps 1–5 and find ΔHf º in Appendix F | Na(s) + [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex]Cl2(g) → NaCl(s) ΔHf º = -411 kJ |

| Table 3. | |

We can write:

ΔH = ΔHf° = ΔH°sublimation + [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex]D + IE + (-EA) + (-ΔHlattice)

Thus, the lattice energy can be calculated from other values. For sodium chloride, using this data, the lattice energy is:

ΔHlattice = (411 + 109 + 121 + 496 + 368) kJ = 769 kJ

The Born-Haber cycle may also be used to calculate any one of the other quantities in the equation for lattice energy, provided that the remainder is known. For example, if the relevant enthalpy of sublimation ΔH°sublimation, ionization energy (IE), bond dissociation enthalpy, lattice energy ΔHlattice, and standard enthalpy of formation ΔHf° are known, the Born-Haber cycle can be used to determine the electron affinity of an atom.

Key Concepts and Summary

The strength of a covalent bond is measured by its bond dissociation energy, that is, the amount of energy required to break that particular bond in a mole of molecules. Multiple bonds are stronger than single bonds between the same atoms. The enthalpy of a reaction can be estimated based on the energy input required to break bonds and the energy released when new bonds are formed. For ionic bonds, the lattice energy is the energy required to separate one mole of a compound into its gas phase ions. Lattice energy increases for ions with higher charges and shorter distances between ions. Lattice energies are often calculated using the Born-Haber cycle, a thermochemical cycle including all of the energetic steps involved in converting elements into an ionic compound.

Key Equations

- Bond energy for a diatomic molecule: XY(g) → X(g) + Y(g) ΔH°

- Enthalpy change:

ΔHreaction = ∑ (energy of bonds broken) - ∑ (energy of bonds formed) - Lattice energy for a solid MX: MX(s) → Mn+(g) + Xn-(g) ΔHlattice

- Lattice energy for an ionic crystal:

ΔHlattice = [latex]\frac{\text{C}(\text{Z}^+)(\text{Z}^-)}{\text{R}_0}[/latex]

Glossary

- bond energy

- (also, bond dissociation energy) energy required to break a covalent bond in a gaseous substance

- Born-Haber cycle

- thermochemical cycle relating the various energetic steps involved in the formation of an ionic solid from the relevant elements

- lattice energy (ΔHlattice)

- energy required to separate one mole of an ionic solid into its component gaseous ions

Chemistry End of Section Exercises

- Which bond in each of the following pairs of bonds is the strongest?

- C–C or C=C

- C–N or C≡N

- C≡O or C=O

- H–F or H–Cl

- C–H or O–H

- C–N or C–O

- Using the bond energies in Table 1, determine the approximate enthalpy change for each of the following reactions:

- H2(g) + Br2(g) ⟶ 2HBr(g)

- CH4(g) + I2(g) ⟶ CH3I(g) + HI(g)

- C2H4(g) + 3O2(g) ⟶ 2CO2(g) + 2H2O(g)

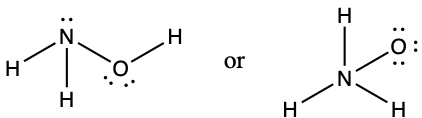

- When a chemical formula can generate two different molecular structures (isomers), the structure with the stronger bonds is usually the more stable form. Use bond energies to predict the more stable molecule with the formula H3NO, hydroxylamine:

- How does the bond energy of HCl(g) differ from the standard enthalpy of formation of HCl(g)?

- Using the standard enthalpy of formation data in Appendix F, show how the standard enthalpy of formation of HCl(g) can be used to determine the bond energy.

- Using the standard enthalpy of formation data in Appendix F, determine which bond is stronger: the S–F bond in SF4(g) or in SF6(g)?

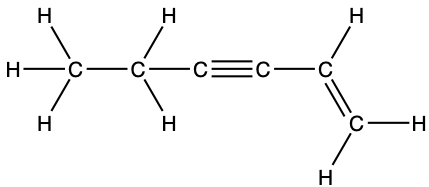

- Complete the following Lewis structure by adding bonds (not atoms), and then indicate the longest bond:

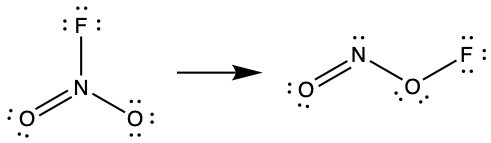

- Use the bond energy to calculate an approximate value of ΔH for the following reaction. Which is the more stable form of FNO2?

- Use principles of atomic structure to answer each of the following:[1]

- The radius of the Ca atom is 197 pm; the radius of the Ca2+ ion is 99 pm. Account for the difference.

- The lattice energy of CaO(s) is –3460 kJ/mol; the lattice energy of K2O is –2240 kJ/mol. Account for the difference.

- Given these ionization values, explain the difference between Ca and K with regard to their first and second ionization energies.

Element First Ionization Energy (kJ/mol) Second Ionization Energy (kJ/mol) K 419 3050 Ca 590 1140 Table 4. - The first ionization energy of Mg is 738 kJ/mol and that of Al is 578 kJ/mol. Account for this difference.

- The lattice energy of LiF is 1023 kJ/mol, and the Li–F distance is 200.8 pm. NaF crystallizes in the same structure as LiF but with a Na–F distance of 231 pm. Which of the following values most closely approximates the lattice energy of NaF: 510, 890, 1023, 1175, or 4090 kJ/mol? Explain your choice.

- For which of the following substances is the least energy required to convert one mole of the solid into separate ions?

- MgO

- SrO

- KF

- CsF

- MgF2

- The reaction of a metal, M, with a halogen, X2, proceeds by an exothermic reaction as indicated by this equation: M(s) + X2(g) → MX2(s). For each of the following, indicate which option will make the reaction more exothermic. Explain your answers.

- a large radius vs. a small radius for M+2

- a high ionization energy vs. a low ionization energy for M

- an higher bond energy for the halogen vs. a lower bond energy for the halogen

- a lower electron affinity for the halogen vs. a higher electron affinity for the halogen

- a larger size of the anion formed by the halogen vs. a smaller size of the anion formed by the halogen

Answers to Chemistry End of Section Exercises

- (a) C=C; (b) C≡N; (c) C≡O; (d) H-F; (e) O-H; (f) C-O

- (a) −103 kJ; (b) 55 kJ; (c) −1324 kJ

- The greater bond energy is in the figure on the left. It is the more stable form.

- The enthalpy of formation is -431.6 kJ, while the bond energy of H-Cl is -431 kJ. They are practically the same.

- [latex]\begin{array}{l l} \text{HCl}(g) \longrightarrow \frac{1}{2} \text{H}_2(g) + \frac{1}{2} \text{Cl}_2(g) & \Delta H^{\circ}_1 = - \Delta H^{\circ}_{\text{f}[\text{HCl}(g)]} \\[1em] \frac{1}{2} \text{H}_2(g) \longrightarrow \text{H}(g) & \Delta H^{\circ}_2 = \Delta H^{\circ}_{\text{f}[\text{H}(g)]} \\[1em] \rule[-1.3ex]{23em}{0.1ex}\hspace{-23em}\frac{1}{2} \text{Cl}_2(g) \longrightarrow \text{Cl}(g) & \Delta H^{\circ}_3 = \Delta H^{\circ}_{\text{f}[\text{Cl}(g)]} \\[1em] \text{HCl}(g) \longrightarrow \text{H}(g) + \text{Cl}(g) & \Delta H^{\circ}_{298} = \Delta H^{\circ}_{1} + \Delta H^{\circ}_{2} + \Delta H^{\circ}_{3} \end{array}[/latex]

[latex]\begin{array}{l @{{}={}} l} D_{\text{HCl}} = \Delta H^{\circ}_{298} &= -\Delta H^{\circ}_{\text{f}[\text{HCl}(g)]} + \Delta H^{\circ}_{\text{f}[\text{H}(g)]} + \Delta H^{\circ}_{\text{f}[\text{Cl}(g)]} \\[1em] &= -(-92.307 \;\text{kJ}) + 217.97 \;\text{kJ} + 121.3 \;\text{kJ} \\[1em] &= 431.6 \;\text{kJ} \end{array}[/latex] - The S–F bond in SF4 is stronger.

-

, the C–C single bonds are longest.

, the C–C single bonds are longest. - ΔH = 82 kJ, the left one is more stable.

- (a) When two electrons are removed from the valence shell, the Ca radius loses the outermost energy level and reverts to the lower n = 3 level, which is much smaller in radius.

(b) The +2 charge on calcium pulls the oxygen much closer compared with K, thereby increasing the lattice energy relative to a less charged ion.

(c) Removal of the 4s electron in Ca requires more energy than removal of the 4s electron in K because of the stronger attraction of the nucleus and the extra energy required to break the pairing of the electrons. The second ionization energy for K requires that an electron be removed from a lower energy level, where the attraction is much stronger from the nucleus for the electron. In addition, energy is required to unpair two electrons in a full orbital. For Ca, the second ionization potential requires removing only a lone electron in the exposed outer energy level.

(d) In Al, the removed electron is relatively unprotected and unpaired in a p orbital. The higher energy for Mg mainly reflects the unpairing of the 2s electron. - 890 kJ/mol. The lattice energy of NaF is less than that that of LiF because of the longer Na-F distance. Using ΔHlattice = [latex]\frac{\text{C}(\text{Z}^+)(\text{Z}^-)}{\text{R}_0}[/latex], the lattice energy of NaF is calculated to be 889 kJ/mol.

- (d)

- ΔH = ΔHf° = ΔH°sublimation + ½D + IE + (-EA) + (-ΔHlattice)

a) small M+2 radius will make the reaction more exothermic; lattice energies increases with shorter distances between the ions;

b) low M ionization energy will make the reaction more exothermic (+IE);

c) lower X2 bond energy will make the reaction more exothermic (+½D);

d) higher halogen electron affinity will make the reaction more exothermic (-EA);

e) a smaller size of the anion will make the reaction more exothermic; lattice energies increases with shorter distances between the ions (-ΔHlattice)

- This question is taken from the Chemistry Advanced Placement Examination and is used with the permission of the Educational Testing Service. ↵