26 Energy Forms & Global Relevance (M6Q1)

Introduction

Learning Objectives for Energy Forms & Global Relevance

- Define and identify energy in some of its forms, as well as its global relevance.

| Global Relevance of Energy | Forms of Energy | - Describe units and relative scales of energy, including high and low chemical energy, and exothermic vs. endothermic reactions.

| Units of Energy | Exothermic and Endothermic Processes | Energy is an Intrinsic Component of Physical and Chemical Changes | Energy Changes During Chemical Reactions |

| Key Concepts and Summary | Glossary | End of Section Exercises |

Global Relevance of Energy

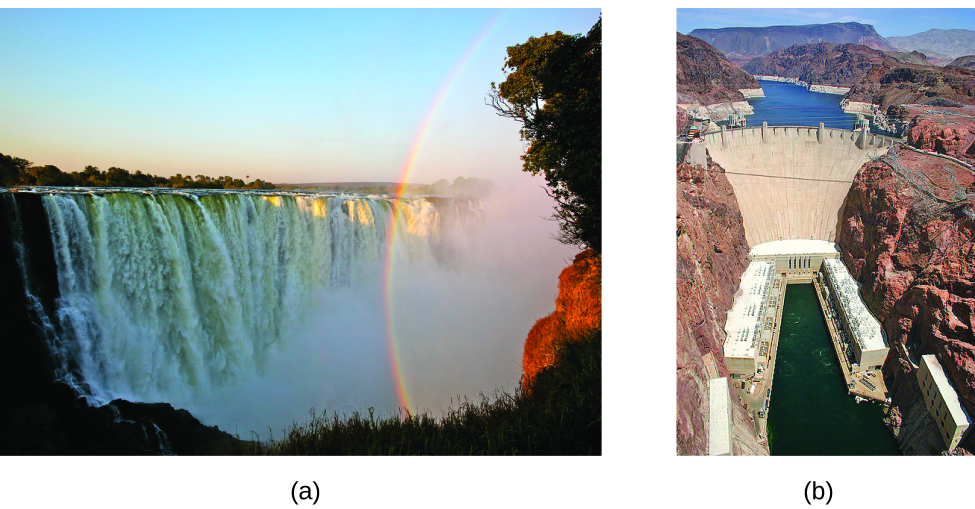

Chemical changes and their accompanying changes in energy are important parts of our everyday world (Figure 1). The macronutrients in food (proteins, fats, and carbohydrates) undergo metabolic reactions that provide the energy to keep our bodies functioning. We burn a variety of fuels (gasoline, natural gas, coal) to produce energy for transportation, heating, and the generation of electricity. Industrial chemical reactions use enormous amounts of energy to produce raw materials (such as iron and aluminum). We also use energy from fuels to manufacture these materials into useful products, such as cars, skyscrapers, and bridges.

Over 90% of the energy that we use comes originally from the sun. Every day, the sun provides the earth with almost 10,000 times the amount of energy necessary to meet all of the world’s energy needs for that day. Our challenge is to find ways that are convenient and nonpolluting to convert and store incoming solar energy so that the energy can be used in reactions or chemical processes. Many plants and bacteria capture solar energy through photosynthesis. We utilize the energy stored in plants when we burn wood or plant products as fuels. We also use this energy to fuel our bodies by eating food that comes directly from plants or from animals that got their energy by eating plants. Burning coal and petroleum also releases stored energy originally from the sun: these fuels are fossilized plant and animal matter.

Scientists from across all disciplines utilize fundamental concepts involving energy in their research. Food scientists use them to determine the energy content of foods. Biologists study the energetics of living organisms, such as the metabolic combustion of sugar into carbon dioxide and water. The oil, gas, and transportation industries, renewable energy providers, and many others seek to find better methods to produce energy for our commercial and personal needs. Engineers strive to improve energy efficiency, find better ways to heat and cool our homes, refrigerate our food and drinks, and meet the energy and cooling needs of computers and electronics, among other applications. Understanding thermochemical principles is essential for chemists, physicists, biologists, geologists, every type of engineer, and just about anyone who studies or does any kind of science.

Forms of Energy

Like matter, energy comes in different types. One scheme classifies energy into two types: potential energy, the energy an object has because of its relative position, composition, or condition, and kinetic energy, the energy that an object possesses because of its motion. You may have talked about kinetic energy in a physics class and used the equation KE = ½mv2, where m is the mass and v is the velocity. Water at the top of a waterfall or dam has potential energy because of its position; when it flows downward through generators, the potential energy is converted into kinetic energy that can be used to do work and produce electricity in a hydroelectric plant (Figure 2). A battery has potential energy because the chemicals within it can produce electricity that can do work.

Energy can be converted from one form into another, but all of the energy present before a change occurs always exists in some form after the change is completed. This observation is expressed in the law of conservation of energy: during a chemical or physical change, energy can be neither created nor destroyed, although it can change forms. (This is also one version of the first law of thermodynamics, as you will learn later in this module.)

When one substance is converted into another, there is always an associated conversion of one form of energy into another. Heat is usually released or absorbed, but sometimes the conversion involves light, electrical energy, or some other form of energy. For example, chemical energy (a type of potential energy) is stored in the molecules that compose gasoline. When gasoline is burned within the cylinders of a car’s engine, the rapidly expanding gaseous products of this chemical reaction generate kinetic energy when they move the pistons in an engine, which in turn rotate the wheels and move the car forward.

Units of Energy

Historically, energy was measured in units of calories (cal). A calorie is the amount of energy required to raise one gram of water by 1 degree Celsius (1 kelvin). However, this quantity depends on the atmospheric pressure and the starting temperature of the water. The ease of measurement of energy changes in calories has meant that the calorie is still frequently used. The Calorie (with a capital C), or large calorie, commonly used in quantifying food energy content, is a kilocalorie (1 Cal = 1 kcal = 1000 cal). The SI unit of heat, work, and energy is the joule. A joule (J) is defined as the amount of energy used when a force of 1 newton moves an object 1 meter. It is named in honor of the English physicist James Prescott Joule. One joule is equivalent to 1 kg m2 s-2. A kilojoule (kJ) is 1000 joules. Another useful conversion factor: 1 calorie = 4.184 joules.

In humans, metabolism is typically measured in Calories per day. A nutritional calorie (i.e., Calorie) is the energy unit used to quantify the amount of energy derived from the metabolism of foods; one Calorie is equal the amount of energy needed to heat 1 kg of water by 1 °C.

Chemistry in Real Life: Measuring Nutritional Calories

In your day-to-day life, you may be more familiar with energy being given in Calories, or nutritional calories, which are used to quantify the amount of energy in foods. One calorie (cal) = exactly 4.184 joules, and one Calorie (note the capitalization) = 1000 cal, or 1 kcal. (This is approximately the amount of energy needed to heat 1 kg of water by 1 °C.)

The macronutrients in food are proteins, carbohydrates, and fats or oils. Proteins provide about 4 Calories per gram, carbohydrates also provide about 4 Calories per gram, and fats and oils provide about 9 Calories/g. Nutritional labels on food packages show the caloric content of one serving of the food, as well as the breakdown into Calories from each of the three macronutrients.

Exothermic and Endothermic Processes

Matter undergoing chemical reactions and physical changes can release or absorb heat. A change that releases heat is called an exothermic process. For example, the combustion reaction that occurs when using an oxyacetylene torch is an exothermic process—this process also releases energy in the form of light as evidenced by the torch’s flame (Figure 3). A reaction or change that absorbs heat is an endothermic process. A cold pack used to treat muscle strains provides an example of an endothermic process. When the substances in the cold pack (water and a salt such as ammonium nitrate) are brought together, the resulting process absorbs heat from your skin, lowering its temperature and leading to the sensation of cold.

Energy is an Intrinsic Component of Physical and Chemical Changes

Later in this module we will examine physical and chemical changes more quantitatively. Here we introduce the concepts from a qualitative perspective.

Recall from the section on Classification of Matter at the beginning of the semester, when a substance undergoes a physical change, such as melting or freezing, the physical state of that substance changes. The process can be endothermic or exothermic. For example, the melting of water is endothermic and requires the addition of energy. Energy can be thought of as a reactant in the process.

energy + H2O(s) ⟶ H2O(l) endothermic process

In contrast, the freezing of water is exothermic and releases energy. Energy can be thought of as a product in the process.

H2O(l) ⟶ H2O(s) + energy exothermic process

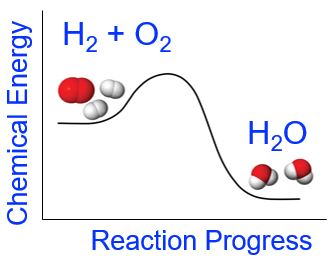

During a chemical change, bonds are broken and formed. For example, when we ignite a balloon containing hydrogen and oxygen gases, water is formed. In simplest terms, one O-O bond and two H-H bonds must be broken in the reactants, and four O-H bonds must be formed in the products. (In reality, it's more complicated.) Energy is released during this reaction as light, heat, and sound.

O2(g) + 2 H2(g) ⟶ 2 H2O(l) + energy exothermic reaction

Demonstration: An exothermic reaction releases energy

Set up. In this demonstration, we want to focus on the balloons containing a mix of H2 and O2 gases (starting around 1:20 in the movie). When these balloons are ignited, a chemical reaction takes place. During this chemical reaction, bonds are broken and formed.

Explanation. This demonstration shows that this reaction is an exothermic reaction. We observe energy being released in the forms of light, heat, and sound. While the one O-O bond and two H-H bonds require energy to be broken, the formation of the four O-H bonds in the products release energy. Since more energy is released upon formation of the products than is required for the breaking up of the reactants, this reaction is exothermic overall.

The electrolysis of water, in contrast, is an endothermic process. In simplest terms, energy is required to break four O-H bonds in the reactants. Next, energy is released upon the formation of one O-O bond and two H-H bonds in the products. The energy released upon bond formation is less than the amount of energy required to break the bonds in the reactants. A battery must be hooked up to continuously supply energy to make this reaction occur.

2 H2O(l) + energy ⟶ O2(g) + 2 H2(g) endothermic reaction

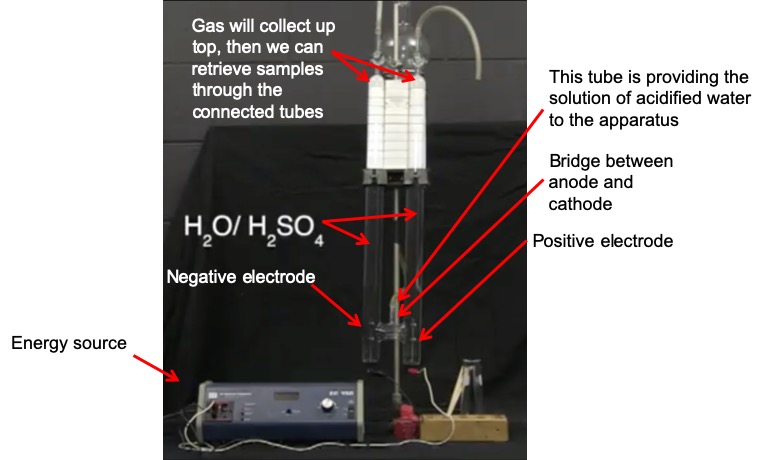

Demonstration: An endothermic reaction requires energy

Set up. In this demonstration (which we also looked at in an earlier module), electrolysis is performed on a solution of water that has been slightly acidified with H2SO4. The sulfuric acid acts as the electrolyte in this demonstration, carrying the charge between the anode and cathode. A DC voltage is applied to two electrodes, labeled "DC (-)" and "DC (+)". These are the anode (positive electrode) and cathode (negative electrode), respectively. The following image explains the different parts of the apparatus that you will see in the video.

When the energy source is turned on, you will see small bubbles appear in the two columns of solution. These bubbles are filled with H2 and O2 gas. These bubbles will float upward and gather at the top of the columns. We can then collect samples of the gas and ignite them to show that they are indeed H2 and O2 gas.

Explanation. At the frame that is labeled "20 minutes later", you can see how much gas has been collected in each column. These columns were filled with solution at the beginning of the experiment, but now one column (the left column, negative electrode) has less solution than the other (and therefore it has more gas). The left column actually contains twice the amount of gas as the right column. This is because H2 is collected in the left column and O2 is collected in the right column. According to the stoichiometry of the reaction, for every one O2 that is produced, two H2 molecules are produced:

2 H2O(l) + energy ⟶ O2(g) + 2 H2(g)

This reaction would not have occurred if we did not turn on the energy source, though. This reaction required an input of energy, and is therefore an endothermic reaction.

![]()

Can you explain why H2 is produced in the left column and O2 is produced in the right column? It may be helpful to look at the overall reaction equation and also review oxidation-reduction reactions from earlier in the semester.

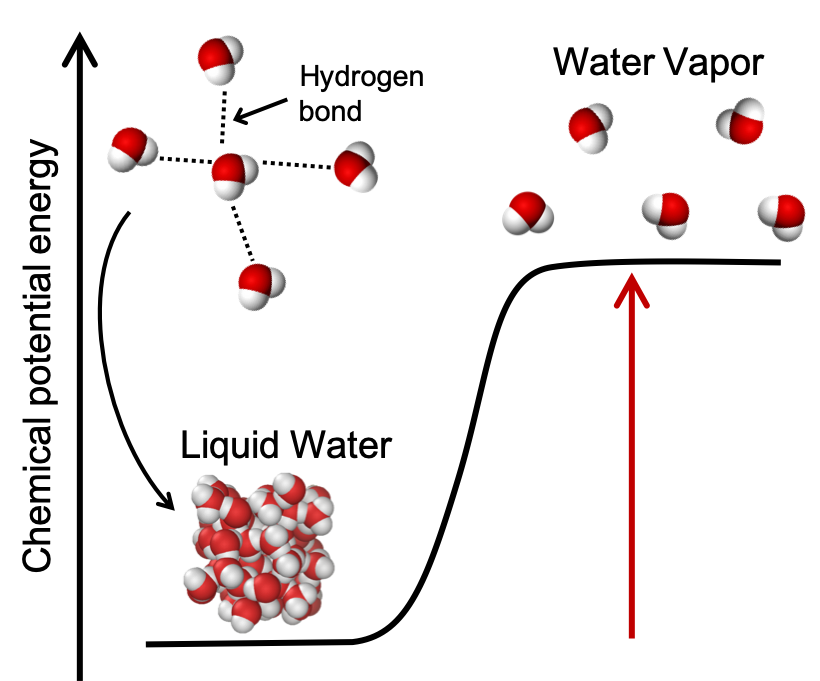

Energy Changes During Chemical Reactions

Breaking bonds is always an endothermic process and requires energy, whether it occurs during a physical or chemical change. Breaking stronger bonds requires a larger input of energy compared to breaking weaker bonds. Forming bonds is a always an exothermic process and releases energy, whether it occurs during a chemical or physical change. This is perhaps less intuitive than the breaking of bonds requiring energy, but keep in mind that the formation of stronger bonds in the end product will result in a more stable product in comparison to the initial reactant. The formation of stronger bonds releases more energy than the formation of weaker bonds.

For example, melting and evaporation are both endothermic physical changes because hydrogen bonds between water molecules are broken. We shall quantify the energy changes occurring during melting and evaporation later in this module, and we'll learn about hydrogen bonds in a later module on intermolecular forces. As an introduction and shown in Figure 4, liquid water is lower in energy than water vapor. Upon heating, the hydrogen bonds between water molecules in liquid water are broken and the chemical potential energy of the water increases. Liquid water molecules are close together and interacting through lots of hydrogen bonds. The water vapor molecules are further apart and are no longer interacting through hydrogen bonds. Note that the energy needed to break the hydrogen bonds does not "disappear" or is "used up" but manifests itself as an increase in potential energy of the sample of water vapor compared to the liquid water as the molecules are now further apart.

Chemical reactions are more complex than simple physical changes as they usually involve both bond breaking and bond making. A chemical reaction will be endothermic (or exothermic) depending on the overall energy changes that occur during the chemical reaction. For example, in the case of the formation of water from elemental hydrogen and oxygen (which we looked at in the demonstration above), the reactants have greater chemical potential energy than the products (Figure 5). The energy required to break the reactant's bonds is less than the energy released upon the formation of the bonds in the products. Overall, the change in energy for this chemical reaction is that more energy is released upon formation of the H-O bonds in water than is required to break apart the H-H and O-O bonds in the reactants. The net release of energy is observed as light, heat, and sound.

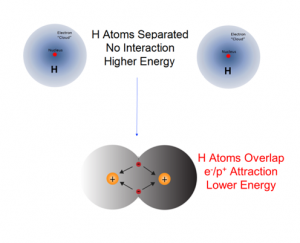

What is the source of chemical potential energy? If in a chemical change the reactants become stable products with a lower chemical potential energy, the electrostatic attractive forces between and within the atoms and molecules of the products are stronger compared to those in the initial reactants. For example, when an H2 molecule forms from two separate H atoms, the electrons in the product molecule will be subject to the attractive forces of the two protons resulting in the formation of a more stable diatomic molecule with a lower chemical potential energy. Because energy is conserved, any energy difference between the potential energies of the reactants and products must be accounted for. It is equal to the energy evolved during the reaction.

Substances with a high chemical potential are not necessarily easy to spot as the energy is not visually apparent unless a chemical reaction takes place and the evolution of energy is obvious. However, knowledge of what a substance is used for can be very helpful. Organic fuels and foods are substances that release large amounts of energy as they are burned or metabolized to form very stable water and carbon dioxide. Substances with a low chemical potential energy are stable and one would expect to find large quantities of them that have been present, unchanged, for a long time. Inorganic rocks have low chemical potential energy. We do not eat rocks!

Demonstration: Exploding gummi bear

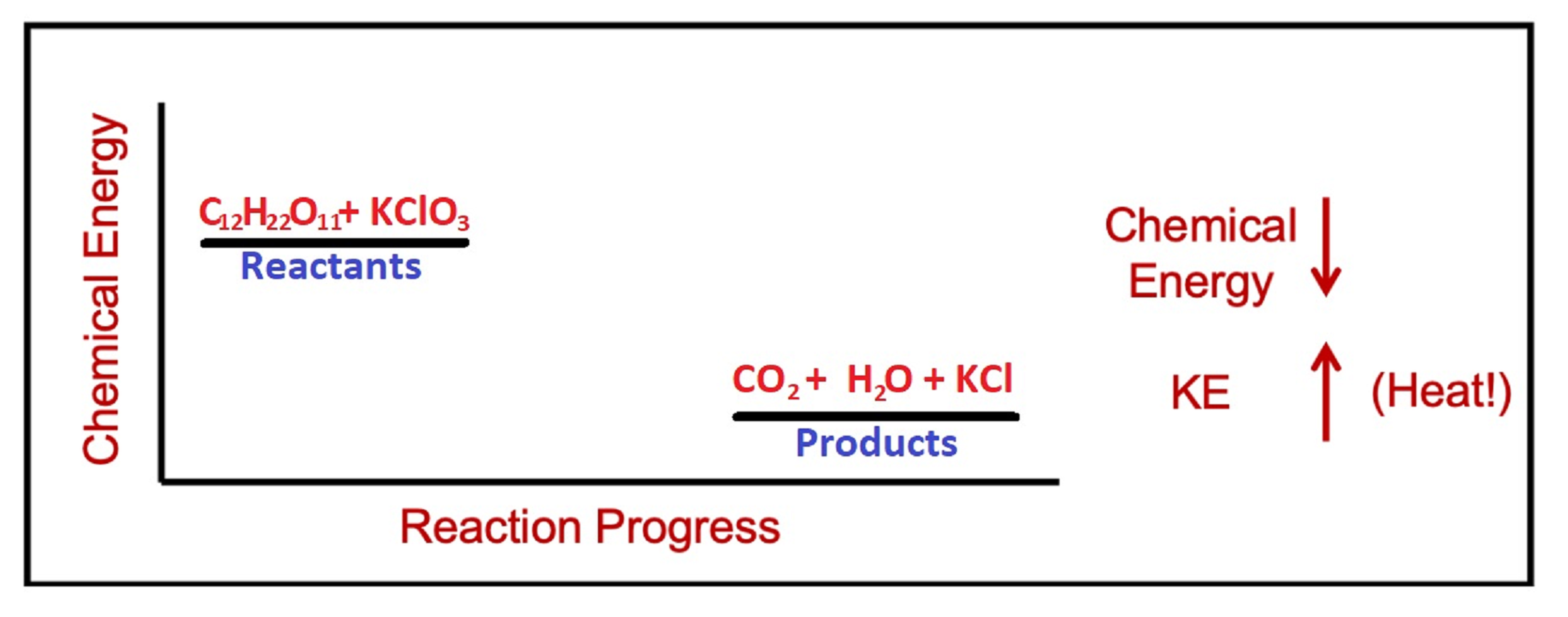

Set up. In the following demonstration, we will observe the exothermic reaction of an exploding gummi bear. First, a test tube with KClO3(s) is heated with a bunsen burner to melt the potassium chlorate. Molten potassium chlorate is a strong oxidizing agent that reacts violently with sugar. So once the molten potassium chlorate has been formed, adding a gummi bear to the test tube will cause a highly exothermic reaction.

Explanation. Gummi bears are made primarily of sugar, C6H12O6. When the sugar comes into contact with the strong oxidizing agent KClO3, a violent exothermic reaction occurs, producing heat and light. The reaction for this part is:

C12H22O11(s) + 8 KClO3(l) → 12 CO2(g) + 11 H2O(g) + 8 KCl(s)

Exothermic reactions like this one have a net decrease in chemical energy as the reaction progresses.

Key Concepts and Summary

Kinetic energy (KE) is the energy of motion; potential energy (PE) is energy due to relative position, composition, or condition. When energy is converted from one form into another, the total energy stays constant (the law of conservation of energy or first law of thermodynamics). Chemical and physical processes can absorb energy (endothermic) or release energy (exothermic). The SI unit of energy, heat, and work is the joule (J). Breaking bonds is always endothermic, while forming bonds is always exothermic. Whether the overall reaction is endothermic or exothermic will depend on the relative amount of energy that is required and released in the reaction process.

Glossary

- calorie (cal)

- unit of heat or other energy; the amount of energy required to raise 1 gram of water by 1 degree Celsius; 1 cal is defined as 4.184 J

- endothermic process

- chemical reaction or physical change that absorbs heat

- energy

- the capacity to supply heat or do work, which we discuss in detail in the next few sections

- exothermic process

- chemical reaction or physical change that releases heat

- joule (J)

- SI unit of energy; 1 joule is the kinetic energy of an object with a mass of 2 kilograms moving with a velocity of 1 meter per second, 1 J = 1 kg m2/s and 4.184 J = 1 cal

- kinetic energy

- energy of a moving body, in joules, equal to [latex]\frac{1}{2}\text{m}v^2[/latex] (where m = mass and v = velocity)

- potential energy

- energy of a particle or system of particles derived from relative position, composition, or condition

- thermal energy

- kinetic energy associated with the random motion of atoms and molecules

- thermochemistry

- study of measuring the amount of heat absorbed or released during a chemical reaction or a physical change

Chemistry End of Section Exercises

- Which of the following substances would you expect to have a relatively high chemical potential energy: Wood, Gasoline, Chalk, Water, Hydrogen Gas?

Answers to Chemistry End of Section Exercises

- Wood, Gasoline, Hydrogen Gas